Smooth newt

The smooth newt, northern smooth newt or common newt (Lissotriton vulgaris) is a species of newt commonly found throughout Europe, except the far north, areas of Southern France and the Iberian Peninsula.[4] It is closely related with several similar species that were previously classified as subspecies.

| Smooth newt | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Urodela |

| Family: | Salamandridae |

| Genus: | Lissotriton |

| Species: | L. vulgaris |

| Binomial name | |

| Lissotriton vulgaris (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| Subspecies[2] | |

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Over 60,[3] including:

| |

Taxonomy

Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus described the smooth newt in 1758 as Lacerta vulgaris, placing it in the same genus as the green lizards.[5]:206 Later, the species was included in the genus Triturus, along with most European newts. This genus however was found to be polyphyletic, containing several unrelated lineages,[6][7][8] and the small-bodied newts, including the smooth newt, were therefore split off as separate genus Lissotriton in 2004.[9]:233 This genus name had first been introduced by the English zoologist Thomas Bell in 1839, and the smooth newt is the genus' type species.[10]:132 The genus name combines Greek λισσός, lissós for "smooth" and the name of Triton, the ancient Greek god of the sea, while the species epithet vulgaris means "common" in Latin.[11]:17

Three subspecies are currently accepted: L. v. vulgaris, L. v. ampelensis and L. v. meridionalis. Four former subspecies from southern Europe and west Asia are now recognised as separate species, as they are morphologically and genetically distinct: the Greek smooth newt (L. graecus), Kosswig's smooth newt (L. kosswigi), the Caucasian smooth newt (L. lantzi) and Schmidtler's smooth newt (L. schmidtleri). The five smooth newt species and the Carpathian newt (L. montadoni), which is their sister species, have collectively been referred to as the "smooth newt species complex".[3][2][12]

To distinguish the smooth newt from its close relatives, the English name "northern smooth newt" has been suggested.[12] Other common names that have been used in the literature include: common newt, great water-newt, common water-newt, warty eft, water eft, common smooth newt, small newt, small eft, small evet, and brown eft.[3]

Description

Smooth newts reach around 9–11 cm (3.5–4.3 in) head-to-tail length in males and 8–9.5 cm (3.1–3.7 in) in females. Outside the breeding season, they have a dry and velvety skin, and both sexes are yellow-brown, brown or olive-brown. Their head is longer than wide, and the elongated snout is blunt in the male and rounded in the female. The male has dark, round spots, while the females have smaller spots which are sometimes form two or more irregular lines along the back. Throat and belly in males are orange to white with small dark, rounded spots (lighter and with smaller spots in the female).[13]:26[14]:233–234

During breeding season, males develop a denticulated crest, which runs uninterruptedly along the back and the tail. It is 1–1.5 mm high at mid-body, but higher along the tail. The tail also has a lower fin, and its end is pointed. The cloaca of breeding males is swollen, round and dark-coloured. The hindfeet have more ore less well developed toe flaps, depending on the subspecies. Colours in general are more vivid than during the land phase. The dark spots grow larger, and the crest often has vertical dark and bright bands. The lower edge of the tail is red with a silver-blue flash and black spots. Females only develop low, straight tail fins but no crest or toe flaps, and are more drably coloured.[13]:26[14]:233–234

There are slight differences in male secondary characters between subspecies: L. v. ampelensis has strongly developed toe flaps, its tail tapers into a fine thread (but not a distinct filament), and the body is slightly square in cross-section. L. v. meridionalis also has toe flaps and a pointed tail, its crest is smooth-edged, and its body is square-shaped. In the nominate subspecies, L. v. vulgaris, the crest is clearly denticulated, toe flaps are only weakly developed and the body is round.[14]:234–236

Similar species

The smooth newt can be confused with other Lissotriton species, with which it sometimes hybridises. Diagnostic features are also mainly observed in the males during the breeding season:

- Carpathian newt (L. montadoni): The crest is very low and smooth-edged; toe flaps are weakly developed; the tail ends in a filament. The underside is yellow or orange, without spots, and there are few spots on the sides.[14]:229–230

- Caucasion smooth newt (L. lantzi): The crest has an almost spine-shaped denticulation.[14]:235

- Greek smooth newt (L. graecus): The crest is less than 1 mm high and smooth-edged; the lower tail fin is usually unspotted; the body is square-shaped; toe flaps are well developed.[14]:235

- Kosswig's smooth newt (L. kosswigi): The crest is below 1 mm at mid-body but high at the tail base and smooth-edged; the tail ends in a long filament; the body is square-shaped; toe flaps are well developed.[14]:234

- Palmate newt (L. helveticus): The crest is smooth-edged; the tail ends in a filament (also in females); toe flaps are well developed. The belly has few or no spots and the throat is always unspotted.[14]:225

- Schmidtler's smooth newt (L. schmidtleri): the dorsal crest reaches 2 mm or more in height and is denticulated; the tail end is elongated but does not have a filament; the body is slightly square-shaped; toe flaps are only weakly developed. This species reaches only 5–7 cm (2.0–2.8 in) in length.[14]:235

Distribution and habitats

The smooth newt has been described as "the most ubiquitous and widely distributed newt of the Old World". The nominate subspecies, L. v. vulgaris, is most widespread and found from Ireland and Great Britain in the west to Siberia in the east, bordered by the dry Eurasian steppe. In the north, it reaches central Fennoscandia. It is absent from southern France, the Iberian peninsula, Italy and most of the Mediterranean islands as well as much of the higher Alps. The subspecies L. v. ampelensis occurs in the Carpathians of Ukraine and the Danube delta of northern Romania, and L. v. meridionalis in the northern half of Italy, southern Switzerland, Slovenia and Croatia.[14]:234–237

In the Carpathians, the smooth newt generally prefers lower elevations than the Carpathian newt (L. montadoni). In the Balkans, from Dalmatia southwards, it is replaced by the Greek smooth newt (L. graecus), while the precise contact zone with Schmidtler's smooth newt (L. schmidtleri) in Bulgaria is not yet clear.[15][12][14]:234–238

The smooth newt is typically a lowland species, ranging up to about 1,000 m (3,300 ft) but reaches 2,150 m (7,050 ft) in Austria.[16]:46-47 It tolerates a wide range of natural and semi-natural habitats, from wooden areas, damp meadows and field edges to parks and gardens, and can be found in urban areas. The newts hide under structures such as logs or stones or in small mammal burrows. Water bodies from small puddles to larger ponds or quiet parts of streams are accepted as breeding sites.[15][14]:–238

The nominate subspecies, L. v. vulgaris, has been introduced to south-eastern Australia. It first recorded near Melbourne in 2011, and larvae were found. This made it the first naturalised salamander species in the southern hemisphere. The newts probably originated from the pet trade, through which they were available before being declared a "controlled pest animal" in 1997. Negative impacts on the native fauna are feared, including predation and competition, toxicity, and disease spread. The smooth newt could spread further in south-eastern Australia, as large areas have a suitable climate.[17]

Lifecycle and behaviour

_(8619564032).jpg)

Smooth newts live on land during most of the year and are mainly nocturnal. They also usually hibernate on land, often in congregations of several newts in shelters such as under logs or in burrows. The efts turn into mature adults at two to three years, and an overall age of 6–14 years can be reached in the wild.[14]:238

Reproduction

Migration to the breeding sites occurs as soon as February, but in the northern parts of the range and at higher altitudes, it may not start before summer. After entering the water, the breeding characters, especially the male's crest, take a few weeks to develop.[14]:238

Mating involves an intricate courtship display: The male attempts to attract a female's attraction by swimming in front of her and sniffing her cloaca. He then vibrates his tail against his body, sometimes violently lashing it, thereby fanning pheromones towards her. In the final phase, he moves away from her, the tail quivering. If she is still interested, she will follow him and touch his cloaca with her snout, whereupon he deposits a packet of sperm (a spermatophore). He then guides her over the spermatophore so she picks it up with her cloaca. Males often try to lead females away from displaying competitors.[14]:238–240

Eggs are fertilised internally, and progeny of one female usually has multiple fathers. It has been shown that females tend to mate preferentially with unrelated males, probably to avoid inbreeding depression.[18]

Females lay 100–500 eggs, usually folding them into waterplants. The eggs are 1.3–1.7 mm in diameter (2.7–4 mm with jelly capsule) and light brown to greenish or grey in colour. Larvae typically hatch after 10–20 days, depending on temperature, and metamorphose into terrestrial efts after around three months. Paedomorphism, where adults retain their gills and stay aquatic, occurs regularly.[14]:238–240

Diet and predators

Smooth newts, including the larvae, are unselective carnivores, feeding mainly on diverse invertebrates such as earthworms, snails or insects, or smaller plankton. Cannibalism also occurs, mainly by preying on eggs of its own species. Various predators eat smooth newts, including waterbirds, snakes and frogs, but also larger newts such as the northern crested newt (Triturus cristatus).[14]:238

Conservation status in Europe

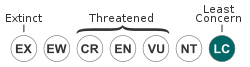

All species of newts are protected in Europe. Laws prohibit the killing, destruction, and the selling of newts. While the species is by no means endangered, IUCN lists insufficient data to make an assessment for two of the subspecies.

In the UK, the smooth newt is protected under Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 with respect to sale only. It is therefore illegal to sell individuals of the species, but their destruction or capture is still permitted. They are also listed under Annex III of the Bern Convention. The smooth newt is the only newt native to Ireland, and it is protected there under the Wildlife Acts (1976 and 2000). It is an offence to capture or kill a newt in Ireland without a licence.[19]

As indicated in the foregoing section, while smooth newts are a protected species in Europe, they were declared a 'controlled pest animal' in the state of Victoria, Australia, in 1997, and prohibited Australia-wide in 2010, due to their invasive potential.

References

- Jan Willem Arntzen, Sergius Kuzmin, Trevor Beebee, Theodore Papenfuss, Max Sparreboom, Ismail H. Ugurtas, Steven Anderson, Brandon Anthony, Franco Andreone, David Tarkhnishvili, Vladimir Ishchenko, Natalia Ananjeva, Nikolai Orlov, Boris Tuniyev (2009) Lissotriton vulgaris. In: IUCN 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2.

- Pabijan, M.; Zieliński, P.; Dudek, K.; Stuglik, M.; Babik, W. (2017). "Isolation and gene flow in a speciation continuum in newts". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 116: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2017.08.003. ISSN 1055-7903.

- Frost, D.R. (2020). "Lissotriton vulgaris (Linnaeus, 1758). Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 6.1". New York, USA: American Museum of Natural History. doi:10.5531/db.vz.0001. Retrieved 18 April 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Nature: Smooth Newt. BBC (2012-04-27). Retrieved on 2013-01-03.

- Linnaeus, C. (1767). Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis (in Latin) (10 ed.). Stockholm, Sweden: L. Salvii. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.37256.

- Titus, T.A.; Larson, A. (1995). "A molecular phylogenetic perspective on the evolutionary radiation of the salamander family Salamandridae". Systematic Biology. 44 (2): 125–151. doi:10.1093/sysbio/44.2.125. ISSN 1063-5157.

- Weisrock, D.W.; Papenfuss, T.J.; Macey, J.R.; et al. (2006). "A molecular assessment of phylogenetic relationships and lineage accumulation rates within the family Salamandridae (Amphibia, Caudata)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 41 (2): 368–383. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.05.008. ISSN 1055-7903.

- Steinfartz, S.; Vicario, S.; Arntzen, J.W.; Caccone, Adalgisa (2007). "A Bayesian approach on molecules and behavior: reconsidering phylogenetic and evolutionary patterns of the Salamandridae with emphasis on Triturus newts". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 308B (2): 139–162. doi:10.1002/jez.b.21119. ISSN 1552-5007.

- García-París, M.; Montori, A.; Herrero, P. (2004). Amphibia: Lissamphibia. Fauna Iberica. 24. Madrid: Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. ISBN 8400082923.

- Bell, T. (1839). "A History of British Reptiles". London: John van Voorst. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.5498. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Große, W-R. (2011). Der Teichmolch [The smooth newt]. Die neue Brehm-Bücherei (in German). 117. Magdeburg, Germany: VerlagsKG Wolf. ISBN 978-3-89432-476-6. ISSN 0138-1423.

- Wielstra, B.; Canestrelli, D.; Cvijanović, M.; et al. (2018). "The distributions of the six species constituting the smooth newt species complex (Lissotriton vulgaris sensu lato and L. montandoni) – an addition to the New Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles of Europe" (PDF). Amphibia-Reptilia. 39: 252–259.

- Beebee, T & Griffiths, R. (2000) The New Naturalist: Amphibians and reptiles- a natural history of the British herpetofauna; Harper Collins Publishers, London.

- Sparreboom, M. (2014). Salamanders of the Old World: The Salamanders of Europe, Asia and Northern Africa. Zeist, The Netherlands: KNNV Publishing. doi:10.1163/9789004285620. ISBN 9789004285620.

- Kuzmin, S. (1999). "AmphibiaWeb – Lissotriton vulgaris". Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Arnold, E. Nicholas; Ovenden, Denys W. (2002). Field Guide: Reptiles & Amphibians of Britain & Europe. Collins & Co. ISBN 9780002199643.

- Tingley, R.; Weeks, A.R.; Smart, A.S.; et al. (2014). "European newts establish in Australia, marking the arrival of a new amphibian order" (PDF). Biological Invasions. 17 (1): 31–37. doi:10.1007/s10530-014-0716-z. ISSN 1387-3547.

- Jehle, R.; Sztatecsny, M.; Wolf, J.B.W; et al. (2007). "Genetic dissimilarity predicts paternity in the smooth newt (Lissotriton vulgaris)". Biology Letters. 3 (5): 526–528. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0311. PMC 2391198. PMID 17638673.

- National Parks & Wildlife Service. Npws.ie. Retrieved on 2013-01-03.

Further reading

"The Life Cycle of the Newt". British Film Council. 1942. Retrieved 24 April 2014.