Smallest organisms

The smallest organisms found on Earth can be determined according to various aspects of organism size, including volume, mass, height, length, or genome size.

_immature_male.jpg)

Given the incomplete nature of scientific knowledge, it is possible that the smallest organism is undiscovered. Furthermore, there is some debate over the definition of life, and what entities qualify as organisms; consequently the smallest known organism (microorganism) is debatable.

Microorganisms

Viruses

Many biologists consider viruses to be non-living because they lack a cellular structure and cannot metabolize by themselves, requiring a host cell to replicate and synthesize new products. A minority of scientists hold that, because viruses do have genetic material and can employ the metabolism of their host, they can be considered organisms. Also, an emerging concept that is gaining traction among some virologists is that of the virocell, in which the actual phenotype of a virus is the infected cell, and the virus particle is merely a reproductive or dispersal stage, much like pollen or a spore.[1]

The smallest viruses in terms of genome size are single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) viruses. Perhaps the most famous is the bacteriophage Phi-X174 with a genome size of 5386 nucleotides.[2] However, some ssDNA viruses can be even smaller. For example, Porcine circovirus type 1 has a genome of 1759 nucleotides[3] and a capsid diameter of 17 nm.[4] As a whole, the viral family geminiviridae is about 30 nm in length. However, the two capsids making up the virus are fused; divided, the capsids would be 15 nm in length. Other environmentally characterized ssDNA viruses such as CRESS DNA viruses, among others, can have genomes that are considerably less than 2,000 nucleotides.[5][6]

The smallest RNA viruses in terms of genome size are small retroviruses such as rous sarcoma virus with genomes of 3.5 kilo base pairs (kb) and particle diameters of 80 nanometres (nm). The smallest double-stranded DNA viruses are the hepadnaviruses such as Hepatitis B, at 3.2 kb and 42 nm; parvoviruses have smaller capsids, at 18-26 nm, but larger genomes, at 5 kb. It is important to consider other self-replicating genetic elements, such as satelliviruses, viroids and ribozymes.

Obligate endosymbiotic bacteria

The genome of Nasuia deltocephalinicola, a symbiont of the European pest leafhopper, Macrosteles quadripunctulatus, consists of a circular chromosome of 112,031 base pairs.[7]

The genome of Nanoarchaeum equitans is 490,885 nucleotides long.

Pelagibacter ubique

Pelagibacter ubique is one of the smallest known free-living bacteria, with a length of 370 to 890 nm and an average cell diameter of 120 to 200 nm. They also have the smallest free-living bacterium genome: 1.3Mbp, 1354 protein genes, 35 RNA genes. They are one of the most common and smallest organisms in the ocean, with their total weight exceeding that of all fish in the sea.[8]

Mycoplasma genitalium

Mycoplasma genitalium, a parasitic bacterium which lives in the primate bladder, waste disposal organs, genital, and respiratory tracts, is thought to be the smallest known organism capable of independent growth and reproduction. With a size of approximately 200 to 300 nm, M. genitalium is an ultramicrobacterium, smaller than other small bacteria, including rickettsia and chlamydia. However, the vast majority of bacterial strains have not been studied, and the marine ultramicrobacterium Sphingomonas sp. strain RB2256 is reported to have passed through a 220 nm ultrafilter. A complicating factor is nutrient-downsized bacteria, bacteria that become much smaller due to a lack of available nutrients.[9]

Nanoarchaeum

Nanoarchaeum equitans is a species of microbe 200 to 500 nm in diameter. It was discovered in 2002 in a hydrothermal vent off the coast of Iceland by Karl Stetter. A thermophile that grows in near-boiling temperatures, Nanoarchaeum appears to be an obligatory symbiont on the archaeon Ignicoccus; it must be in contact with the host organism to survive.

Eukaryotes

Prasinophyte algae of the genus Ostreococcus are the smallest free-living eukaryote. The single cell of an Ostreococcus measures 0.8 μm across.

Animals

Several species of Myxozoa (obligately parasitic cnidarians) never grow larger than 20 µm.[10] One of the smallest species (Myxobolus shekel) is no more than 8.5 µm when fully grown.[11]

Bivalvia

The shell of the nut clam Condylonucula maya grows 0.54 mm long.[12]

Gastropods

The smallest water snail (of all snails) is Ammonicera minortalis in North America, originally described from Cuba. It measures 0.32 to 0.46 mm.[13][14]

The smallest land snail is Acmella nana. Discovered in Borneo, and described in November 2015, it measures 0.7 mm.[15] The previous record was that of Angustopila dominikae from China, which was reported in September 2015. This snail measures 0.86 mm.[16]

Smallest crustacean

The smallest crustacean, and indeed the smallest arthropod, is the tantulocarid Stygotantulus stocki, at a length of 94 μm (0.0037 in).[17]

Arachnids

The smallest arachnids are mites of the family Microdispidae, Cochlodispus minimus, at 79 µm long.[18]

Insects

Adult males of the parasitic wasp Dicopomorpha echmepterygis can be as small as 139 μm long, smaller than some species of protozoa (single-cell creatures); females are 40% larger.[19]

Megaphragma caribea from Guadeloupe, measuring 170 μm long, is another contender for smallest known insect in the world.

- Beetles

Beetles of the tribe Nanosellini are all less than 1 mm long; the smallest confirmed specimen is of Scydosella musawasensis at 325 μm long; a few other nanosellines are reportedly smaller, in historical literature, but none of these records have been confirmed using accurate modern tools. These are among the tiniest non-parasitic insects.[20]

- Butterflies

The western pygmy blue (Brephidium exilis) is one of the smallest butterflies in the world, with a wingspan of about 1 centimetre.[21]

Echinoderms

The smallest sea cucumber, and also the smallest echinoderm, is Psammothuria ganapati, a synaptid that lives between sand grains on the coast of India. Its maximum length is 4 mm.[22] [23]

Sea urchins

The smallest sea urchin, Echinocyamus scaber, has a test 6 mm across.[23]

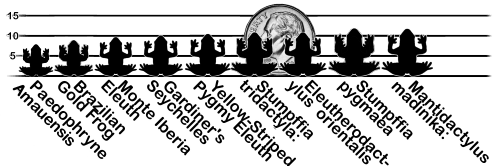

Vertebrates

.png)

The smallest vertebrates (and smallest amphibians) known are Paedophryne amauensis frogs from Papua New Guinea, which range in length from 7.0–8.0 mm (0.28–0.31 in), and average 7.7 mm (0.30 in).[24][25] Previously, the title of smallest vertebrate was held by members of the fish genus Paedocypris of Indonesia.

Fish

One of the smallest fish based on the minimum size at maturity is Paedocypris progenetica from Indonesia, with mature females measuring as little as 7.9 mm (0.31 in) in standard length.[26] This fish, a member of the carp family, has a translucent body and a head unprotected by a skeleton.

One of smallest fish based on the minimum size at maturity is Schindleria brevipinguis from Australia, their females reach 7 mm (0.28 in) and males 6.5 mm (0.26 in),[27] Males of S. brevipinguis have an average standard length of 7.7 mm (0.30 in); a gravid female was 8.4 mm (0.33 in).[28] This fish, a member of the goby family, differs from similar members of the group in having its first anal fin ray further forward, under dorsal fin 4.

Male individuals of the anglerfish species Photocorynus spiniceps have been documented to be 6.2–7.3 mm (0.24–0.29 in) at maturity, and thus claimed to be a smaller species. However, these survive only by sexual parasitism and the female individuals reach the significantly larger size of 50.5 mm (1.99 in).[29][30][31][32]

Amphibians

Salamanders

The average snout-to-vent length (SVL) of several specimens of the salamander Thorius arboreus was 17 mm (0.67 in).

Frogs

Frogs include the smallest vertebrates known. The smallest known frog species is Paedophryne amauensis, with a snout-vent length reported as 7.7 mm, which occurs among leaf-litter in the tropical montane forests of New Guinea. Other very small frogs include Brachycephalus didactylus from Brazil (reported as 9.6–9.8 mm), several species of Eleutherodactylus such as E. iberia (around 10 mm) and E. limbatus (8.5–12 mm) and Eleutherodactylus orientalis (12.5 mm) from Cuba, Gardiner's Frog Sechellophryne gardineri from the Seychelles (up to 11 mm), several species of Stumpffia such as S. tridactyla (8.6–12 mm) and S. pygmaea (males 10–12.5 mm; females: 11 mm) and Wakea madinika (males: 11–13 mm; females: 15–16 mm) from Madagascar. Paedophryne swiftorum (body length 8.5 mm) is not included in the smallest vertebrates known with other nine species of frogs.[33] The two species Microhyla borneensis (males:10.6–13 mm; females:16–19 mm)[34][35] and Arthroleptella rugosa (males: 11.9–14.1 mm; females:15.5mm) were once the smallest known frogs from the Old World. In general these extremely small frogs occur in tropical forest and montane environments. There is relatively little data on size variation among individuals, growth from metamorphosis to adulthood or size variation among populations in these species. Additional studies and the discovery of further minute frog species are likely to change the rank order of this list.

Reptiles

Lizards

Two geckos, the dwarf gecko (Sphaerodactylus ariasae) and the Virgin Islands dwarf sphaero (S. parthenopion), are the smallest known reptile species and smallest lizard, with a snout-vent length of 16 millimetres (0.63 in).[36] A few Brookesia chameleons from Madagascar are equally small, with a reported snout-vent length of 15–18 mm for male dwarf chameleons (B. minima), 14–19 mm for male Mount d'Ambre leaf chameleons (B. tuberculata)[37] and 15–16 mm for male B. micra,[38] though females are larger.

Of the aforementioned geckos, S. ariasae was first described in 2001 by the biologists Blair Hedges and Richard Thomas. This dwarf gecko lives in Jaragua National Park in the Dominican Republic and on Beata Island (Isla Beata), off the southern coast of the Dominican Republic.[39][40]

Turtles

The smallest turtle is the speckled padloper tortoise (Homopus signatus) from South Africa. The males measure 6–8 cm (2.4–3.1 in), while females measure up to almost 10 cm (3.9 in).[41]

Crocodilians

The smallest crocodilian is the Cuvier's dwarf caiman (Paleosuchus palpebrosus) from northern and central South America. It reaches up to 1.6 m (5.2 ft) in length.[42]

Snakes

One of the smallest snakes known is the recently discovered Barbados threadsnake (Leptotyphlops carlae). Adults average about 10 cm (4 in) long, which is only about twice as long as the hatchlings. The Common blind snake (Indotyphlops braminus) measures 5.1–10.2 cm (2–4 in) long, occasionally up to 15 cm (6 in) long.[43][44]

Dinosaurs

The smallest avian dinosaur is the bee hummingbird. The smallest known extinct dinosaur is Anchiornis, a genus of feathered dinosaur that lived in what is now China during the Late Jurassic Period 160 to 155 million years ago. Adult specimens range from 34 cm (13 in) long, and the weight has been estimated at up to 110 g (3.9 oz).[45] Nevertheless, sizes of dinosaurs are commonly labelled with a level of uncertainty, as the available material often (or even usually) is incomplete. Oculudentavis is even smaller than Anchiornis, but it is uncertain if it is in fact an (avialan) dinosaur.

Birds

_immature_male.jpg)

With a mass of approximately 1.8 grams (0.063 oz) and a length of 5 centimetres (2.0 in), the bee hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae) is the smallest bird species, the smallest warm-blooded vertebrate, and smallest known dinosaur. Called the zunzún in its native habitat on Cuba, it is lighter than a Canadian or U.S. penny. It is said that it is "more apt to be mistaken for a bee than a bird".[46] The bee hummingbird eats half its total body mass and drinks eight times its total body mass each day. Its nest is 3 cm across.

Mammals

The vulnerable Kitti's hog-nosed bat (Craseonycteris thonglongyai), also known as the bumblebee bat, from Thailand and Myanmar[47] is the smallest mammal, at 3–4 centimetres (1.2–1.6 in) in length and 1.5–2 grams (0.053–0.071 oz) in weight.

The Etruscan shrew (Suncus etruscus), is the smallest mammal by mass, weighing about 1.8 g (0.063 oz) on average.[48] The bumblebee bat has a smaller skull size. The smallest mammal that ever lived, the shrew-like Batodonoides vanhouteni, weighed 1.3 grams (0.046 oz).

Rodents

The smallest member of the rodent order is the Baluchistan pygmy jerboa, with an average body length of 4.4 cm (1.7 in).[49]

Carnivorans

The smallest member of the order Carnivora is the least weasel (Mustela nivalis), with an average body length of 114–260 mm (4.5-10.2 in). It weighs between 29.5 – 250 grams with females being lighter.

Marsupials

The smallest marsupial is the long-tailed planigale from Australia. It has a body length of 110–130 millimetres (4.3–5.1 in) (including tail) and weigh 4.3 grams (0.15 oz) on average.

The Pilbara ningaui is considered to be of similar size and weight.[49]

Primates

The smallest member of the primate order is Madame Berthe's mouse lemur (Microcebus berthae), found in Madagascar,[50] with an average body length of 92 mm (3.6 in).

Plants

Flowering plants (angiosperms)

Duckweeds of the genus Wolffia are the smallest flowering plants.[51] Fully grown, they measure 300 µm by 600 µm and reach a mass of just 150 µg.

Other

Nanobes

Nanobes are thought by some scientists to be the smallest known organisms,[52] about one tenth the size of the smallest known bacteria. Nanobes, tiny filamental structures first found in some rocks and sediments, were first described in 1996 by Philippa Uwins of the University of Queensland.

See also

- Human timeline

- Largest organisms

- Largest prehistoric organisms

- Life timeline

- Nature timeline

References

- P. Forterre (2012). "The virocell concept and environmental microbiology". The ISME Journal. 7 (2): 233–236. doi:10.1038/ismej.2012.110. PMC 3554396. PMID 23038175.

- Sanger, F.; Air, G. M.; Barrell, B. G.; Brown, N. L.; Coulson, A. R.; Fiddes, J. C.; Hutchison, C. A.; Slocombe, P. M.; Smith, M. (1977). "Nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage ΦX174 DNA". Nature. 265 (5596): 687–95. Bibcode:1977Natur.265..687S. doi:10.1038/265687a0. PMID 870828.

- Finsterbusch T, Mankertz A (2009). "APorcine circoviruses--small but powerful". Virus Research. 143 (2): 177–183. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2009.02.009. PMID 19647885.

- ICTVdB Virus Description – 00.016.0.01.005. Porcine circovirus 2 Archived July 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- K. Rosario; R.O. Schenck; R.C. Harbeitner; S.N. Lawler; M. Breitbart (2015). "Novel circular single-stranded DNA viruses identified in marine invertebrates reveal high sequence diversity and consistent predicted intrinsic disorder patterns within putative structural proteins". Frontiers in Microbiology. 6: 696. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00696. PMC 4498126. PMID 26217327.

- J.M. Labonté; C.A. Suttle (2013). "Previously unknown and highly divergent ssDNA viruses populate the oceans". The ISME Journal. 7 (11): 2169–2177. doi:10.1038/ismej.2013.110. PMC 3806263. PMID 23842650.

- Bennett, Gordon M.; Abbà, Simona; Kube, Michael; Marzachì, Cristina (25 February 2016). "Complete Genome Sequences of the Obligate Symbionts "Candidatus Sulcia muelleri" and "Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola" from the Pestiferous Leafhopper Macrosteles quadripunctulatus (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae)". Genome Announcements. 4 (1): e01604–15. doi:10.1128/genomeA.01604-15. ISSN 2169-8287. PMC 4722273. PMID 26798106.

- "Pelagibacter ubique - microbewiki". microbewiki.kenyon.edu. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- "Re: What is the smallest living thing?". Madsci.org. Retrieved 2013-10-03.

- Fiala, Ivan. 2008. Myxozoa. Version 10 July 2008 (under construction). http://tolweb.org/Myxozoa/2460/2008.07.10 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

- Kaur, H; Singh, R (2011). "Two new species of Myxobolus (Myxozoa: Myxosporea: Bivalvulida) infecting an Indian major carp and a cat fish in wetlands of Punjab, India". J Parasit Dis. 35 (2): 169–76. doi:10.1007/s12639-011-0061-4. PMC 3235390. PMID 23024499.

- Abele, Doris; Brey, Thomas; Philipp, Eva (15 February 2017). "Part N, Revised, Volume 1, Chapter 7: Ecophysiology of Extant Marine Bivalvia". Treatise Online. doi:10.17161/to.v0i0.6583.

- Páll-Gergely, Barna; Hunyadi, András; Jochum, Adrienne; Asami, Takahiro (28 September 2015). "Seven new hypselostomatid species from China, including some of the world's smallest land snails (Gastropoda, Pulmonata, Orthurethra)". ZooKeys (523): 31–62. doi:10.3897/zookeys.523.6114. PMC 4602296. PMID 26478698.

- Sankar-Gorton, Eliza (4 November 2015). "Newly Discovered Land Snail Is The Tiniest In The World". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- Geggel, Laura (2 November 2015). "Micro Mollusk Breaks Record for World's Tiniest Snail". LiveScience. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- Páll-Gergely, Barna; Hunyadi, András; Jochum, Adrienne; Asami, Takahiro (2015). "Seven new hypselostomatid species from China, including some of the world's smallest land snails (Gastropoda, Pulmonata, Orthurethra)". ZooKeys (523): 31–62. doi:10.3897/zookeys.523.6114. PMC 4602296. PMID 26478698.

- Joel W. Martin & George E. Davis (2001). An Updated Classification of the Recent Crustacea (PDF). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. pp. 132 pp. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2008.

- Alain Fraval (2015). "Micro-insecte". Insectes (76): 22.

- "University of Florida Book of Insect Records". Entnemdept.ifas.ufl.edu. 1998-04-17. Archived from the original on 2013-10-05. Retrieved 2013-10-03.

- Polilov, A.A. (2015). "How small is the smallest? New record and remeasuring of Scydosella musawasensis Hall, 1999 (Coleoptera, Ptiliidae), the smallest known free-living insect". ZooKeys (526): 61–64. doi:10.3897/zookeys.526.6531. PMC 4607844. PMID 26487824.

- "Facts on the Western Pygmy Blue Butterfly".

- Rao, G. Chandrasekhara (1968). "On Psammothuria ganapatii n. gen. n. sp., an interstitial holothurian from the beach sands of waltair coast and its autecology". Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences, Section B. 67 (5): 201–206. doi:10.1007/BF03053902 (inactive 2020-04-02).

- Gilpin, Daniel (2006). Starfish, urchins, and other echinoderms. London: David West Children's Books. p. 41. ISBN 0-7565-1611-0.

- "World's tiniest frogs found in Papua New Guinea". The Australian. 12 January 2012. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- Rittmeyer, Eric N.; Allison, Allen; Gründler, Michael C.; Thompson, Derrick K.; Austin, Christopher C. (2012). "Ecological guild evolution and the discovery of the world's smallest vertebrate". PLOS One. 7 (1): e29797. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...729797R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029797. PMC 3256195. PMID 22253785.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). "Paedocypris progenetica" in FishBase. September 2017 version.

- News, Opening Hours 9 30am-5 00pmMonday- SundayClosed Christmas Day Address 1 William StreetSydney NSW 2010 Australia Phone +61 2 9320 6000 www australianmuseum net au Copyright © 2019 The Australian Museum ABN 85 407 224 698 View Museum. "Fishes". The Australian Museum.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). "Schindleria brevipinguis" in FishBase. September 2017 version.

- "Scientists find 'smallest fish'". BBC News. 2006-01-25. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- "What is the smallest species of fish?". Amonline.net.au. 2013-09-27. Archived from the original on February 20, 2009. Retrieved 2013-10-03.

- "Smallest fish compete for honours". BBC News. 2006-01-31. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- "Bragging Rights: The Smallest Fish Ever | LiveScience". Archived from the original on July 6, 2008.

- Krishna Ramanujan (2012-03-29). "Student researchers help discover world's smallest frog". Cornell Chronicle. Retrieved 2012-01-03.

- "Tiny, new, pea-sized frog is old world's smallest". ScienceDaily.

- "Bornean Chorus Frog - Microhyla borneensis (Microhyla nepenthicola)". www.ecologyasia.com.

- Pennsylvania State University (2001). World's Smallest Lizard Discovered in the Caribbean. Accessed 26 January 2009.

- Glaw, F., & Vences, M. (2007). A Field Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of Madagascar, 3d edition. Frosch Verlag. ISBN 978-3-929449-03-7

- Glaw, F.; Köhler, J. R.; Townsend, T. M.; Vences, M. (2012). Salamin, Nicolas (ed.). "Rivaling the World's Smallest Reptiles: Discovery of Miniaturized and Microendemic New Species of Leaf Chameleons (Brookesia) from Northern Madagascar". PLOS One. 7 (2): e31314. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731314G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031314. PMC 3279364. PMID 22348069.

- "Tiny gecko is 'world's smallest'". BBC News. 2001-12-03. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2002-11-04. Retrieved 2011-12-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Branch, B. (1998). Field Guide to Snakes and other Reptiles of Southern Africa. 3d edition. Struik Publishers. ISBN 1-86872-040-3

- CROCODILIANS Natural History & Conservation. Paleosuchus palpebrosus.

- "Indotyphlops braminus :: Florida Museum of Natural History". www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu.

- "Blind Snakes". www.reptilesmagazine.com.

- Xu, X., Zhao, Q., Norell, M., Sullivan, C., Hone, D., Erickson, G., Wang, X., Han, F. and Guo, Y. (2009). "A new feathered maniraptoran dinosaur fossil that fills a morphological gap in avian origin." Chinese Science Bulletin, 6 pages, accepted November 15, 2008.

- "mschloe.com - Diese Website steht zum Verkauf! - Informationen zum Thema mschloe". ww1.mschloe.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013.

- Bates, P.; Bumrungsri, S. & Francis, C. (2008). "Craseonycteris thonglongyai". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T5481A11205556. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T5481A11205556.en. Listed as Vulnerable

- Jürgens, Klaus D. (August 2002). "Etruscan shrew muscle: the consequences of being small". Journal of Experimental Biology. 205 (15): 2161–2166. PMID 12110649. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "World's Smallest Animals". Thetoptenz.net. 2013-09-29. Retrieved 2013-10-03.

- (Retrieved on March 17, 2010). Archived July 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "What is the smallest flower in the world?". Loc.gov. Retrieved 2013-10-03.

- Nanjundiah, V. (2000). "The smallest form of life yet?" (PDF). Journal of Biosciences. 25 (1): 9–10. doi:10.1007/BF02985175. PMID 10824192.

External links

- Featherwing beetles on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site