Silat Melayu

Silat Melayu (Jawi: سيلت ملايو), also known as Seni Persilatan Melayu[3] ('art of Malay Silat') or simply Silat, is a combative art of self-defence from the Malay world, that employs langkah ('steps') and jurus ('movements') to ward off or to strike assaults, either with or without weapons. Silat traced its origin to the early days of Malay civilisation, and has since developed into a fine tradition of physical and spiritual training that embodies aspects of traditional Malay attire, performing art and adat. The philosophical foundation of modern Malay Silat is largely based on the Islamic spirituality.[4] Its moves and shapes are rooted from the basis of Silat movements called Bunga Silat, and Silat performances are normally accompanied with Malay drum assembles.[5]

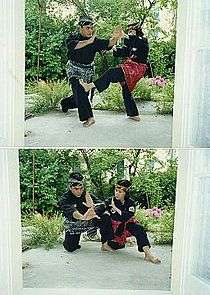

A Singaporean pesilat | |

| Also known as | Seni Persilatan Melayu[1] |

|---|---|

| Focus | Striking |

| Hardness | Full-contact, semi-contact, light-contact |

| Country of origin | Malay world[2] |

| Olympic sport | No |

| Silat | |

|---|---|

| Country | Malaysia |

| Reference | 1504 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2019 |

The term Silat is also employed to refer to similar fighting styles in areas with significant Malay cultural influence, in modern day Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, Brunei and Vietnam. In Indonesia, the term Pencak Silat, a composite of recent origin from the late 1940s, deriving from the Sundanese/Javanese word Penca(k) and the Minangkabau word Silek or Malay word Silat,[6] has been used as an umbrella term of traditional martial arts of Indonesia.[7] In Malay terminology, the term 'Pencak Silat' is also used, but more in referring to the exoteric aspect of the fighting style, in contrast to the esoteric aspect of Silat called Seni Silat ('the art of Silat'). In other words, 'pencak' (fighting) can be regarded as the zahir (outer/exoteric knowledge), whilst seni pertains to the whole of Silat including batin (inner/esoteric knowledge) and zahir. Seni Silat is thus considered to be a deeper level of understanding. Therefore, it is said that each aspect of Silat emanates from seni (art), including both the fighting and the dance aspects.[8]

Regionally, Silat is governed by PERSIB (National Pencak Silat Federation of Brunei Darussalam) in Brunei, PESAKA (National Silat Federation of Malaysia) in Malaysia and PERSISI (Singapore Silat Federation) in Singapore. These governing bodies, together with IPSI (Indonesian Pencak Silat Association), are the founding members of International Pencak Silat Federation (PERSILAT). The sport version of Silat is one of the sports included in the Southeast Asian Games and other region-wide competitions, under the name 'Pencak Silat'. Pencak silat first made its debut in 1987 Southeast Asian Games and 2018 Asian Games, both were held in Indonesia. Silat was recognized as a piece of Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO in 2019.[9]

Etymology

Due to lack of written records, the origin of the word 'Silat' remains uncertain. One writer suggests that Malay term 'Silat' is linked to Minangkabau word Silek, thus a Sumatran origin of the term is likely.[10] This theory is however refuted by another author, suggesting that the Minangkabau style is originated from the crude form of Malay Silat instead.[11] Among the earliest written record of Silat was from Misa Melayu written by Raja Chulan sometime between 1720–1786, that described 'silat' as a fighting style in general.[12] Before the word 'Silat' is being used, the Malay martial arts were generally known as ilmu perang ('military knowledge'), ilmu hulubalang ('knowledge of Hulubalang'), ilmu prajurit ('knowledge of soldiers') in literature.[13] As Silat is regarded as an indigenous art form, the concept of Ilmu, defined as mystical knowledge and as science, is a central component of the art. It was said that the practice of Silat requires about eighty percent of knowledge, and only twenty percent of physical training.[14]

According to the Malay oral literature, the word 'Silat' is said to originate from the Arabic word 'silah' (سِلَاح) meaning 'weapon'[15] or 'silah' (صِلَةُ) meaning 'connection'.[16] Over the time, the word is believed to has been malayised into 'Silat' in similar way the word karamah (كرامة) was malayised into keramat (کرامت) ('sacred') and the word 'hikmah' (حكمة) was malayised into hikmat (حکمت) ('supernatural power'). This etymological root suggests that Silat is philosophically based on the teaching of Islam, which over the centuries, have become the source of a Malay identity. The use of the Arabic word serves as a tool in elaborating the philosophy of both Malay culture and art itself. The 'connection' in the etymology suggests that Silat covers aspects in the relationship between humans, between humans and their enemies, and between human and nature, and ultimately attaining the spirituality, that is the relationship between human and their creator.[17]

The word 'Silat' is also said to originate from the composite of two words 'si' and 'elat'. 'Si' is a Malay article used with adjectives to describe people, and normally found in names and nicknames. While 'elat' is a verb means 'to trick', 'to confuse' or 'to deceive'. The derivative transitive verb 'menyilat' or 'menyilap' carries the meaning of an action to evade, to trick or to take an assault, together with a counterattack.[18]

Other etymological root suggests that the word is said to derive from 'silap' (to make a mistake). This means that using the opponent’s strength against them—in their strength lies their weakness. This strength could be physical or psychological. Others suggested that it originated from the word sekilat meaning “as fast as lightening” derived from kilat (lightning); sila (as in silsilah or chain) indicating the transmission of Silat from guru to murid (disciple of Silat or other religious or secular knowledge); and more mysteriously, from the Arabic solat (prayer), although linguists regard solat as an unlikely candidate for the etymological root of 'Silat'. Other contenders for the etymological root of 'Silat' include the 'Orang Selat' (an indigenous Malay people of Singapore), and selat as in Selat Melaka (the Straits of Malacca).[19] English-language publications are sometimes mistakenly refer to Silat Melayu as bersilat but this is actually a verb form of the noun Silat, literally meaning "to perform Silat".

History

Early period

The genesis of traditional Malay martial arts has been attributed to the need for self-defense, hunting techniques and military training in ancient Malay world. Hand-to-hand combat and weapons practice were important in training warriors for combat in human warfare. Early traditional fighting styles believed to have been developed among various Malayic tribes from the dawn of the Malayic civilisation, 2000 years ago.[20][21] Movements of these early fighting styles epitomize the movements of various animals such as the crocodile, tiger and eagle, and deeply influenced by ancient Malay animism.[22] The Kra Isthmus region of the Malay peninsula and its peripheries are recognised by historians as the cradle of Malayic civilisation.[23] Deep in the pristine estuary of the Merbok River, lies an abundance of historical relics of the past. At its zenith, the massive settlement sprawled across a thousand kilometers wide, dominated in the northern plains of Malay Peninsular.[24][25] On contemporary account, the area is known as the lost city of Sungai Batu. Founded in 535 BC, it is among the oldest testament of civilisation in Southeast Asia and a potential progenitor of the Kedah Tua kingdom. By the 2nd century Chinese sources, primordial Malayic kingdoms in the Malay peninsula are described as tributaries to Funan.[26] The most notable of these was a Buddhist kingdom, Langkasuka that was established between 80 to 100 A.D.[27]

The mandala of Langkasuka-Kedah centred in modern-day northern Malay peninsula rose to prominence with the regression of Funan from the 6th century,[28] This confederation, with its city states that controlled both coastal fronts of Malay peninsula, assumed importance in the trading network involving Rome, India and China.[29] The growth in trade brought in foreign influence throughout these city states, most importantly in cultural traits including the combative arts.[30] The influence from both Chinese and Indian martial arts can be observed from the use of weapons such as the Indian mace and the Chinese sword. During this period, formalised combat arts were believed to have been practiced in the Malay peninsula and Sumatra.[31] The arts were refined with the advent of Srivijaya, an important thalassocracy from the 7th century. The Riau Archipelago is particularly noted in the origin and development of Malay martial arts. Romanticized and demonized in former literature as the notoriously dangerous islands that once acted as a trade route and historical thoroughfare in an international trading network, its people Orang Laut also called Orang Selat are stereotyped as “sea pirates”, but historically played major roles in the times of Srivijaya, Melaka Sultanate, and later Johor Sultanate. They patrolled the adjacent sea areas, repelling real pirates, directing traders to their overlords' ports and maintaining those ports' dominance in the area. The fighting styles developed in this area are described by different writers as a crude prototype of Malay martial arts and one of the progenitors of modern Malay Silat.[32]

Islamic era

The Malay martial arts reached its historical peak with the rise of Islam during the fifteenth century under the Melaka Sultanate.[33] It was during this era that the Islamic philosophy, especially Sufism, began shaping the system of Malay martial arts, in addition to the introduction of a standard Malay clothing in the early form of Baju Melayu,[34] that later became an important uniform worn by Silat practitioners until today.[35]

In the Malay Annals, the martial prowess of the Malay rulers and nobility is dramatically recounted in many colourful vignettes, for example, that of Sultan Alauddin personally apprehending thieves in flight, and chopping one in half “cleaving his waist as though it had been a gourd”. These legends are important because they establish the principle of the divine rule of kings, kings who are said to be the Shadow of God on earth, and because they firmly tie Divine Right to the war machine, Silat.[36] The Malay Annals also contain the exploits of the legendary Laksamana Hang Tuah as a formidable exponent of Malay martial arts, which are still recounted today as an integral part of the cultural legacy of Silat.[37] His duel with one of his companions, Hang Jebat is the famous depiction of a Silat duel in Malay literature and art, and has also become the most controversial subject in Malay culture, concerning on the questions of unconditional loyalty and justice. In Melakan era, the Malay martial arts were generally known as ilmu perang ('military knowledge'), ilmu hulubalang ('knowledge of Hulubalang'), ilmu prajurit ('knowledge of soldiers') in literature.[38]

The Malay martial arts took more sophisticated form with more diverse cultural influence after Melaka became an important centre of international trade, drawing a diverse group of people to its port. The Chams that hailed from modern day Vietnam, is one particularly important group, believed by many archaeologists to have created the prototype of a kris as far back as 2000 years ago.[39] By the 15th century, Islam began to gain some converts among the Chams. After centuries of armed conflicts between Vietnam and Champa, the Vietnamese sacked the Cham capital, Vijaya in 1471. Over the years, after their defeat, increasing number of Chams converted to Islam, inspired in part by the fact that Muslim rulers and their subjects in Melaka, suppported Cham resistance.[40] As a result of their experience in wars, commanders of Champa were known to have been held in high esteem by the Malay kings for their knowledge in martial arts and for being highly skilled in the art of war. As mentioned in the Malay Annals, t is said that Sultan Muhammad Shah had chosen a Cham official as his right hand or senior officer because the Chams possessed skills and knowledge in the administration of the kingdom.[41]

From the 15th century onwards, Malayisation spread many Malay traditions including language, literature, martial arts, and other cultural values throughout Maritime Southeast Asia. Historical accounts note close relationship between Melaka and Brunei Sultanates, leading to the spread of Silat through the region from as early as the 15th century. Brunei's national epic poem, the Syair Awang Semaun, recounts the legend of a strong and brave warrior Awang Semaun who contributed extensively to the development of Brunei, and who is also said to be the younger brother of Awang Alak Betatar, who was crowned the first Sultan of Brunei and reigned as Sultan Muhammad Shah (1405–1415). The fifth Sultan, Bolkiah, who ruled between 1485 and 1524, excelled both in martial art and diplomacy.[42] Under the seventh Sultan, Saiful Rijal (1575–1600), the Sultanate was involved in the Castilian War against the Spanish Empire in 1578, and they would have used Silat and invulnerability practices.[43] Thereafter, several patriots excelled as warriors, including Pengiran Bendahara Sakam under the reign of Sultan Abdul Mubin (1600–1673).[44] As Brunei rose to the status of a maritime power at the crossroads of Southeast Asia, it built the unity of the kingdom through war and conquest, and managed to extend its control over the coastal regions of modern-day Sarawak and Sabah and the Philippines Islands, which were under the Sultanate's control for more than two centuries.[45]

After the fall of Melaka Sultanate in 1511, Malayisation continued shaping the region, under later Malay-Muslim sultanates that emerged in Malay Peninsula, Sumatra and Borneo, the most notable of these were Johor, Perak, and Pattani.[46] Malay Kings encouraged princes and children of dignitaries to learn silat and any other form of knowledge related to the necessities of combat. Prominent fighters were elevated to head war troops and received ranks or bestowals from the raja. This is evidenced in the 19th century Pahang Kingdom where a number of its nobility like Tok Gajah and Dato' Bahaman were themselves prominent Silat masters who have proven their gallantry in several wars like Pahang Civil War and Klang War. Due to lack of written records, the origin of the word 'Silat', and when it began to be used to refer to Malay martial arts remains uncertain. Among the earliest written record of Silat was from Misa Melayu written by Raja Chulan sometime between 1720–1786, that described 'silat' as a fighting style in general.[47]

Colonial and modern era

In the 16th century, conquistadors from Portugal attacked Melaka in an attempt to monopolise the spice trade. The Malay warriors managed to hold back the better-equipped Europeans for over 40 days before Melaka was eventually defeated. The Portuguese hunted and killed anyone with knowledge of martial arts so that the remaining practitioners fled to more isolated areas.[48] Even today, the best silat masters are said to come from rural villages that have had the least contact with outsiders.

For the next few hundred years, the Malay Archipelago would be contested by a string of foreign rulers, namely the Portuguese, Dutch, and finally the British. The 17th century saw an influx of Minangkabau and Bugis people into Malaya from Sumatra and south Sulawesi respectively. Bugis sailors were particularly famous for their martial prowess and were feared even by the European colonists. Between 1666 and 1673, Bugis mercenaries were employed by the Johor Empire when a civil war erupted with Jambi, an event that marked the beginning of Bugis influences in local conflicts for succeeding centuries. By the 1780s the Bugis had control of Johor and established a kingdom in Selangor. With the consent of the Johor ruler, the Minangkabau formed their own federation of nine states called Negeri Sembilan in the hinterland. Today, some of Malaysia's silat schools can trace their lineage directly back to the Minang and Bugis settlers of this period.

After Malaysia achieved independence, Tuan Haji Anuar bin Haji Abd. Wahab was given the responsibility of developing the nation's national silat curriculum which would be taught to secondary and primary school students all over the country. On 28 March 2002, his Seni Silat Malaysia was recognised by the Ministry of Heritage and Culture, the Ministry of Education and PESAKA as Malaysia's national silat. It is now conveyed to the community by means of the gelanggang bangsal meaning the martial arts training institution carried out by silat instructors.[49] Silat Melayu by Disember 2019, received recognition from UNESCO as part of Malaysian Intangible Cultural Heritage.[50]

Styles

Brunei

Silat in Brunei shares characteristics common in the Malay world, but it has also developed specific techniques and practices of its own. Silat as a performing art is traditionally accompanied by an orchestra called gulintangan or gulingtangan (literally: ‘rolling hands’), often composed of a drum (gandang labik) and eight gongs, including a thin gong (canang tiga) and a thick gong (tawak-tawak).[51] There are several styles being practiced in Brunei, and some are influenced by a range of elements from Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines. The most widespread is Gerak 4 1, created by H. Ibrahim, and consisting of the four styles learnt from his masters: Panca Sunda, Silat Cahaya, Silat Kuntau and Silat Cakak Asli. Some of the other styles include Kembang Goyang, Kuntau Iban, Lintau Pelangi (originally from Belait), Pampang Mayat, Pancasukma, Perisai Putih (originally from the East Javanese school Setia Hati), Persatuan Perkasa, Persatuan Basikap, Selendang Merah (‘the red scarf’), Silat Sendi, Tambong, Teipi Campaka Puteh, Gayong Kicih or Kiceh, Gayong Tiga or Permainan Tiga (which includes Gayong, Cimande and Fattani), and Cengkaman Harimau Ghaib.[52]

The different styles of Silat are often practiced among different nationalities, and not according to specific territorial borders. Nevertheless, the foreign influences are rarely clearly expressed by the practitioners. There are many Filipinos and Indonesians in Brunei as migrant workers, but due to their significantly lower social status, the influence of the styles developed in their original countries are not that clearly visible among local styles.[53] This is contributed in part, by the royal and aristocratic status of Silat itself in Malay society, in contrast to the peasant martial arts.[54] At the same time, a variety of local styles fell under the nationalisation drive for a common tradition of Bruneian Silat, bringing other styles of different indigenous groups that occupied the territories that were formerly part of Brunei, into isolation. This led to the abandonment of many details of the Silat practices in favor of a national homogeneity.[55]

In the end, two most widespread styles were established as national ones; Silat Cakak Asli and Silat Kuntau, which both be seen as complementing each other. Cakak Asli focuses more on relaxed moves but sticky-hand techniques in a close combat, to ultimately unbalance the opponent, and hit with the knees, elbows and forehead. Kuntau prioritizes various forms of punches and kicking, and normally done in fast and harsh movements, therefore making it hard to perform lock in a close range combat. These two styles have been patronized in the sultanate for many generation of rulers, but with lack of written records, it is hard to trace their origins and development in Brunei. The 29th sultan, Omar Ali Saifuddien III, was known for having learnt both Silat Cakak Asli and Silat Kuntau and he promoted local Silat in the 1950s, notably by organizing tournaments at the palace.[56]

Malaysia

Silat practiced in Malaysia are diverse, with vast differences in training tools, methods and philosophy across different schools and styles. The variety of styles not only demonstrated many different combat skills, but also the ability of the martial art itself in manifesting different personages and community in warrior traditions. Some forms of Silat also exist especially in the very remote villages, with members consisting of a few students. The modern law and regulations require that the Silat bodies need to be registered as an association or club. Therefore, we find that those silat forms with very few members are those which are being practiced in a secretive way in remote areas and are taught only by invitation of the master. Based on the data from 1975, there were 265 styles of Silat in Malaysia, which in turn grouped into 464 different Silat associations throughout the country. Today, there are 548 associations or communities which actively practicing Silat in Malaysia. Out of these, four associations are the most prominent and became the founding members of Majlis Silat Negara ('National Silat Council') in 1978, later renamed Persekutuan Silat Kebangsaan Malaysia or PESAKA (The National Silat Federation of Malaysia).[57]

The first two associations are Seni Gayung Fatani Malaysia and Silat Seni Gayung Malaysia that represent a style called seni gayong (modern spelling seni gayung). The word gayung in Malay literally means to assault using blades like parang or sword, or it can also can means 'martial art' and synonymous to Silat itself. Gayung also means “single-stick,” a weapon that is associated with magical powers in Malay literature. For the Malay martial artist, gayung is a verb that describes the action of dipping into the well of the unseen, to draw out mystical power for use in this world. Seni Gayung is a composite style, incorporating both Malay Silat and elements from Bugis fighting styles. It is visually distinctive from other Malay styles of Silat due to its emphasis upon performance acrobatics, including flips, diving rolls, somersaults, and handsprings. The student learns to competently handle several weapons, notably the parang, lembing (spear), sarung and the kris.[58]

The next association is Seni Silat Cekak Malaysia that represents a style called Silat Cekak. Silat cekak was originally developed in the Kedah Court, and has been practiced by senior commanders of Kedah army in wars fought against the Siamese. The style is said to has been developed specifically to counter the Thai fighting style, Muay Thai or known locally as tomoi. It is one of the most popular Silat styles in Malaysia, first registered as an association in Kedah in 1904, and for Malaysia generally in 1965. Cekak in Malay means to 'claw' or to seize the opponent. It is renowned for its series of buah (combat strategy) which have been influential in the development of more recent silat styles in Malay peninsula, including seni gayung.[59] Unlike most of styles of Silat, Silat Cekak is known for its non-ceremonious nature with no emphasis in graceful dance-like movements. It is a defensive-type of Silat that applies 99% defending techniques and only 1% attacking techniques. The style has no kuda-kuda stances commonly found in other Silat styles, and it does not utilize any evading nor side stepping techniques in mortal combat. As a result, it is hard to predict movements and counter-attacks of this style.[60][61]

The last association is Seni Silat Lincah Malaysia that represents a style called Silat Lincah. Silat Lincah is said to originate from another older style of Melaka called Silat Tarah, allegedly practiced by Hang Jebat himself, one of the companions of Hang Tuah.[62] The word tarah in Malay means to sever as in cut off, and the term was considered too aggressive for the use of masses, thus it was changed to Lincah. Lincah means fast and aggressive which is the principle of the style, that emphasise aggressive movements both in defense and attacking techniques in punches and kicks. The style favors evasion with follow up sweeps, locks and chokes that do not relate to dueling techniques used with a kris. Similar to Silat Cekak, Silat Lincah put little emphasis to graceful dance-like movements.[63][64]

Singapore

Despite its status as a global city, Singapore still retains a large part of its cultural heritage including Silat. Historically, Silat development in Singapore is closely related to the mainland Malay peninsula, owing to its status as an important city in Malay history from classical to modern era. There are styles being practiced are influenced by a range of elements from both Malaysia and Indonesia, and there are also styles that locally developed and spread to other neighboring countries especially Malaysia. Seni Gayong, one of the biggest Silat styles in Malaysia, was founded in the early 1940s by Mahaguru Datuk Meor Abdul Rahman on Pulau Sudong seven kilometres south of Singapore. Having inherited the art from his maternal grandfather, Syed Zainal Abidin Al-Attas, a prominent pendekar from Pahang,[65] he transformed the style from a parochial past time to a regimented and highly organised form of self defense during the troubled years of the Japanese occupation.[66]

Another notable style originated from Singapore is called Silat Harimau established by Mahaguru Haji Hosni Bin Ahmad in 1974. The styles that inspired by the movements of tiger began to gain popularity in 1975 not only in Singapore but also in Malaysia. It was recoqnised by the Malaysian Martial Arts Federation, as a native Silat of Singapore that represents the city state in various competitions and demonstrations.[67] Haji Hosni went on to establish another style called Seni Silat Al-Haq. It is a style that derives its buah (combat strategy) from both Seni gayung and Silat Cekak, and considered as a more aesthetically polished (halus) style of Seni gayung.[68] There are many other styles of Silat currently found in Singapore but nearly a third of the styles are the result from Haji Rosni's adaptations and innovations. For example, where there was Silat Kuntao Melaka, he created Silat Kuntao Asli, and in the place of Silat Cekak, he created Cekak Serantau.[69]

Thailand

The southernmost provinces of Thailand, located on the Malay peninsula, are culturally and historically related to the states of Malaysia. Similarities are not only found in the spoken language, but also in a variety of Malay cultural aspects including Silat. Despite being suppressed and subjected to Thaification by the central government, the practice of Silat still finds its widespread currency in those provinces. Many different forms of Silat can be found in the Malay Muslim communities in Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat as well as Saba-yoy and Thebha districts from the Songkhla province at its northern reaches, and with southern form s down through Malaysia.[70] Historically, the Thai part of the peninsula and the Malaysian side, have been influencing each other’s styles of Silat for centuries. Silat in Southern Thailand had also significant influence in the development of Thai martial art called Krabi–krabong.[71][72]

Silat Tua, an important Silat style that has an intimate relationship with four elements of nature (earth, water, fire and wind) as understood from its roots in animism, is said to originate from Pattani region. Silat Tua is directly translated as ‘old’ or ‘ancient’ Silat. Described as the 'Malay dance of life', Silat Tua does not has sets of rigid instructions as well as the endless pre-arranged movement patterns like most traditional martial arts, rather it is an art that begins with 'natural movement', focusing on the strengths and weaknesses of the exponent and the potential of the individual body. What is focused instead are basic principles and uses of imagery that are immortalised in freestyle movement known as a tari ('dance'). As Pattani was constantly at war with the neighbouring kingdom of Siam, many combative developments in the art were made in this region leading Silat Tua to take on another name, Silat Pattani.[73]

Uniform

The silat uniform varies according to style and locality but it is generally based on Siamese outfits. People of the Malay Peninsula traditionally wore sarong and carried a roll of cloth which could be used as a bag, a blanket or a weapon. Some schools use a modern uniform consisting of a T-shirt and pants topped with a short sarong. Others may not have any official uniform and allow the students to dress as they normally would, so that they become accustomed to fighting in their daily attire. The standard full dress of today's silat practitioners, both male and female, usually consists of the following:

- The tengkolok and tanjak are headkerchiefs with different ways of tying them depending on status and region. They are traditionally made from songket cloth.

- The baju Melayu (lit. Malay clothes) is a round-collared shirt made from songket cloth. A variant form is the teluk belanga. This term is commonly used in southern Thailand even when referring to a standard baju Melayu.

- The samping (or likat in Thai) is a waistcloth traditionally made from batik cloth. The length varies, traditional types generally being longer. There are a number of ways to tie it but the old style used by warriors was the samping silang which allows for freedom of movement and easy access to weapons worn at the side.

- The bengkung or bengkong is a cloth belt or sash which secures the samping. Some schools colour the bengkung to signify rank, a practice adopted from the belt system of Japanese martial arts. Some silat schools replace the bengkung with a modern buckled belt.

Training hall

In Malay the practice area is called a gelanggang. They were traditionally located outdoors, either in a specially constructed part of the village or in a jungle clearing. The area would be enclosed by a fence made of bamboo and covered in nipah or coconut leaves to prevent outsiders from stealing secrets. Before training can begin, the gelanggang must be prepared either by the teachers or senior students in a ritual called "opening the training area" (buka gelanggang ). This starts by cutting some limes into water and then walking around the area while sprinkling the water onto the floor. The guru walks in a pattern starting from the centre to the front-right corner, and then across to the front-left corner. They then walk backwards past the centre into the rear-right corner, across to the rear-left corner, and finally ends back in the centre. The purpose of walking backwards is to show respect to the gelanggang, and any guests that may be present, by never turning one's back to the front of the area. Once this has been done, the teacher sits in the centre and recites an invocation so the space is protected with positive energy. From the centre, the guru walks to the front-right corner and repeats the invocation while keeping the head bowed and hands crossed. The right hand is crossed over the left and they are kept at waist level. The mantra is repeated at each corner and in the same pattern as when the water was sprinkled. As a sign of humility, the guru maintains a bent posture while walking across the training area. After repeating the invocation in the centre once more, the teacher sits down and meditates. Although most practitioners today train in modern indoor gelanggang and the invocations are often replaced with a prayer, this ritual is still carried out in some form or another.

Performance

Silat can be divided into a number of types, the ultimate form of which is combat. However, there exist forms of performance used either for training or entertainment

Silat Pulut

Silat pulut utilises agility in attacking and defending oneself.[74] In this exercise, the two partners begin some distance apart and perform freestyle movements while trying to match each other's flow. One attacks when they notice an opening in the opponent's defences. Without interfering with the direction of force, the defender then parries and counterattacks. The other partner follows by parrying and attacking. This would go on with both partners disabling and counter-attacking their opponent with locking, grappling and other techniques. Contact between the partners is generally kept light but faster and stronger attacks may be agreed upon beforehand. In another variation which is also found in Chinese qinna, the initial attack is parried and then the defender applies a lock on the attacker. The attacker follows the flow of the lock and escapes it while putting a lock on the opponent. Both partners go from lock to lock until one is incapable of escaping or countering.

This game is called silat pulut or gayong pulut because after a performance each player is gifted with bunga telur and sticky rice or pulut. It goes by various other names such as silat tari (dance silat), silat sembah (obeisance silat), silat pengantin (bridal silat) and silat bunga (flower silat). Silat pulut is held during leisure time, the completion of silat instruction, official events, weddings or festivals where it is accompanied by the rhythm of gendang silat (silat drums) or tanji silat baku (traditional silat music).[75] As with a tomoi match, the speed of the music adapts to the performer's pace.

British colonists introduced western training systems by incorporating the police and sepoys (soldiers who were local citizens) to handle the nation's defence forces which at that time were receiving opposition from former Malay fighters. Consequently, silat teachers were very cautious in letting their art become apparent because the colonists had experience in fighting Malay warriors.[75] Thus silat pulut provided an avenue for exponents to hone their skills without giving themselves away. It could also be used as preliminary training before students are allowed to spar.

Despite its satirical appearance, silat pulut actually enables students to learn moves and their applications without having to be taught set techniques. Partners who frequently practice together can exchange hard blows without injuring each other by adhering to the principle of not meeting force with force. What starts off as a matching of striking movements is usually followed by successions of locks and may end in groundwork, a pattern that is echoed in the modern mixed martial arts.

Others

In Thailand, silat performance can be divided into the following.

- Silat Yatoh: two partners take turns attacking and defending

- Silat Kayor: kris performance, usually at night

- Silat Tari: graceful bare-handed movements traditionally performed for royalty

- Silat Tari Eena: slow movements

- Silat Tari Yuema: mid-paced movements

- Silat Tari Lagoh Galae: fast movements

- Silat Tari Sapaelae: quick movements imitating a warrior in battle

- Silat Taghina: dance-like movements performed to slow music

- Gayong Mat: bare hands

- Gayong Paelae: kris

- Gayong Leeyae: swords

- Ibu Gayong: quick dodges and counters performed by women

Styles

Styles of silat melayu are as follows:

- Lian Padukan

- Seni Gayong

- Seni Gayung Fatani

- Silat Pattani

Weapons

| Weapon | Definition |

|---|---|

| Kris | A dagger which is often given a distinct wavy blade by folding different types of metal together and then washing it in acid. |

| Parang | Machete/ broadsword, commonly used in daily tasks such as cutting through forest growth. |

| Golok | |

| Tombak | Spear/ javelin, made of wood, steel or bamboo that may have dyed horsehair near the blade. |

| Lembing | |

| Tongkat | Staff or walking stick made of bamboo, steel or wood. |

| Gedak | A mace or club usually made of iron. |

| Kipas | Folding fan preferably made of hardwood or iron. |

| Kerambit | A concealable claw-like curved blade that can be tied in a woman's hair. |

| Sabit | Sickle commonly used in farming, harvesting and cultivation of crops. |

| Trisula | Trident, introduced from India |

| Tekpi | Three-pronged truncheon thought to derive from the trident. |

| Chindai | Wearable sarong used to lock or defend attacks from bladed weapons. |

| Samping | |

| Rantai | Chain used for whipping and seizing techniques |

References

- Department of Heritage Malaysia 2018, p. 1

- Farrer 2009, pp. 26 & 61

- Department of Heritage Malaysia 2018, p. 1

- Yahaya Ismail 1989, p. 73

- PSGFM 2016

- Oxford dictionaries, p. Silat

- Harnish & Rasmussen 2011, p. 187

- Farrer 2009, pp. 30–31

- UNESCO 2019

- Green, Thomas A. (2010). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598842432.

- Farrer 2009, p. 29

- Raja Chulan 1966, p. 14

- Anuar Abd Wahab 2008, p. 15

- Farrer 2009, p. 30

- Ahmad Zuhairi Abdul Halim, Hariza Mohd Yusof & Nizamiah Muhd Nor 1999, p. 181

- Department of Heritage Malaysia 2018, pp. 3

- Department of Heritage Malaysia 2018, pp. 2–3

- Tuan Ismail Tuan Soh 1991, p. 16

- Farrer 2009, p. 29

- Alexander 2006, pp. 51–52 & 225

- Abd. Rahman Ismail 2008, p. 188

- Farrer 2009, p. 53

- Barnard 2004, pp. 56–57

- Pearson 2016

- Hall 2017

- Jacq-Hergoualc'h 2002, pp. 101–102

- Grabowsky 1995, p. 195

- Farish A Noor 2011, p. 17

- Mishra 2010, p. 28

- Mishra 2010, p. 28

- James 1994, p. 73

- Farrer 2009, pp. 27–28

- Farrer 2009, pp. 31–34

- Siti Zainon Ismail 2009, p. 167&293

- Farrer 2009, p. 122

- Farrer 2009, pp. 32

- Farrer 2009, p. 34

- Anuar Abd Wahab 2008, p. 15

- Farish A Noor 2000, p. 244

- Juergensmeyer & Roof 2012, p. 1210

- A. Samad Ahmad 1979, p. 75

- Zapar 1989, p. 22

- Dayangku Hajah Rosemaria Pengiran Haji Halus 2009, p. 44

- Zapar 1989, p. 21

- De Vienne 2012, p. 44

- Reid 1993, p. 70

- Raja Chulan 1966, p. 14

- Zainal Abidin Shaikh Awab and Nigel Sutton (2006). Silat Tua: The Malay Dance Of Life. Kuala Lumpur: Azlan Ghanie Sdn Bhd. ISBN 978-983-42328-0-1.

- Martabat Silat Warisan Negara, Keaslian Budaya Membina Bangsa PESAKA (2006) [Sejarah Silat Melayu by Tn. Hj. Anuar Abd. Wahab]

- Silat is ours new Straits Times. Retrieved on December 15 2019

- Facal 2014, p. 4

- Facal 2014, p. 6

- Facal 2014, p. 6

- Farrer 2009, p. 28

- Facal 2014, p. 6

- Facal 2014, p. 6

- National Silat Federation of Malaysia 2018

- Farrer 2009, p. 111

- Farrer 2009, p. 108

- Futrell 2012, p. 60

- Nazarudin Zainun & Mohamad Omar Bidin 2018, p. 7

- Seni Silat Lincah Association of Malaysia 2019

- McQuaid 2012

- Lobo Academy 2019

- Pertubuhan Silat Seni Gayong 2016, p. History of Gayong

- Farrer 2009, p. 110

- Pencak-Silat Panglipur Genève 2019

- Farrer 2009, pp. 112-113

- Farrer 2009, p. 115

- Paetzold & Mason, p. 128

- Hill 2010

- Farrer 2009, p. 29

- Sutton 2018, p. 10

- Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka Dictionary (Teuku Iskandar 1970)

- Martabat Silat Warisan Negara, Keaslian Budaya Membina Bangsa PESAKA (2006) [Istilah Silat by Anuar Abd. Wahab]

Bibliography

- Farrer, Douglas S. (2009), Shadows of the Prophet: Martial Arts and Sufi Mysticism, Springer, ISBN 978-1402093555

- Harnish, David; Rasmussen, Anne (2011), Divine Inspirations: Music and Islam in Indonesia, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195385427

- Yahaya Ismail (1989), The cultural heritage of Malaysia, Dinamika Kreatif, ISBN 978-9839600001

- PSGFM (2016), Silat vs Pencak Silat, Official Website of Seni Gayung Fatani

- Ahmad Zuhairi Abdul Halim; Hariza Mohd Yusof; Nizamiah Muhd Nor (1999), Amalan mistik dan kebatinan serta pengaruhnya terhadap alam Melayu, Tamaddun Research Trust, ISBN 978-9834021900

- Tuan Ismail Tuan Soh (1991), Seni Silat Melayu dengan tumpuan kepada Seni Silat Sekebun, Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, ISBN 978-9836221780

- Anuar Abd Wahab (2008), Silat, Sejarah Perkembangan Silat Melayu Tradisi dan Pembentukan Silat Malaysia Moden, Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, ISBN 978-9834407605

- Department of Heritage Malaysia (2018), Seni Persilatan Melayu/Silat (PDF), Department of Heritage, Ministry of Tourism and Culture Malaysia

- Raja Chulan (1966), Misa Melayu, Kuala Lumpur: Pustaka Antara

- Oxford dictionaries, Oxford dictionaries, Oxford University Press

- Alexander, James (2006), Malaysia Brunei & Singapore, New Holland Publishers, ISBN 1-86011-309-5

- Abd. Rahman Ismail (2008), Seni Silat Melayu: Sejarah, Perkembangan dan Budaya, Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, ISBN 978-983-62-9934-5

- UNESCO (2019), Intangible Cultural Heritage - Silat

- Barnard, Timothy P. (2004), Contesting Malayness: Malay identity across boundaries, Singapore: Singapore University press, ISBN 9971-69-279-1

- Pearson, Michael (2016), Trade, Circulation, and Flow in the Indian Ocean World, Palgrave Series in Indian Ocean World Studies, ISBN 9781137566249

- Hall, Thomas D. (2017), Comparing Globalizations Historical and World-Systems Approaches, ISBN 9783319682198

- Jacq-Hergoualc'h, Michel (2002), The Malay Peninsula: Crossroads of the Maritime Silk-Road (100 Bc-1300 Ad), BRILL, ISBN 90-04-11973-6CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grabowsky, Volker (1995), Regions and National Integration in Thailand 1892-1992, Otto Harrassowitz, ISBN 978-3447036085

- Farish A Noor (2011), From Inderapura to Darul Makmur, A Deconstructive History of Pahang, Silverfish Books, ISBN 978-983-3221-30-1

- Mishra, Patit Paban (2010), The History of Thailand, Greenwood, ISBN 978-0313-340-91-8

- Alexander, James (2006), Malaysia Brunei & Singapore, New Holland Publishers, ISBN 978-1-86011-309-3

- Siti Zainon Ismail (2009), Pakaian Cara Melayu (The way of Malay dress), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia publications, ISBN 978-967-942-740-0

- Farish A Noor (2000), "From Majapahit to Putrajaya: The Kris as a Symptom of Civilizational Development and Decline", South East Asia Research, SAGE Publications, 8 (3): 239–279, doi:10.5367/000000000101297280

- Juergensmeyer, Mark; Roof, Wade Clark (2012), Encyclopedia of Global Religion, SAGE Publications

- A. Samad Ahmad (1979), Sulalatus Salatin (Sejarah Melayu), Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, ISBN 983-62-5601-6

- Milner, Anthony (2010), The Malays (The Peoples of South-East Asia and the Pacific), Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4443-3903-1

- Zapar, H. M. B. H. S. (1989), Silat Cakak Asli Brunei, Persib, Kementerian Kebudayaan, Belia dan Sukan Brunei

- De Vienne, Marie-Sybille (2012), Brunei de la thalassocratie à la rente, CNRS, ISBN 978-2271074430

- Dayangku Hajah Rosemaria Pengiran Haji Halus (2009), Seni Silat Asli Brunei : Perkembangan Dan Masa Depannya, Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka Brunei, ISBN 978-99917-0-650-4

- Facal, Gabriel (2014), "Silat martial ritual initiation in Brunei Darussalam", South East Asia: A Multidisciplinary Journal, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, 14

- National Silat Federation of Malaysia (2018), Founding history

- Futrell, Thom (2012), Many Paths To Peace, Lulu, ISBN 978-1105170454

- Nazarudin Zainun; Mohamad Omar Bidin (2018), Pelestarian Silat Melayu antara Warisan dengan Amalan, Penerbit Universiti Sains Malaysia, ISBN 978-9674611675

- Seni Silat Lincah Association of Malaysia (2019), Mahaguru & Founder

- Lobo Academy (2019), Silat Styles

- McQuaid, Scott (2012), The Scriptures of Hang Tuah, Black Triangle Silat

- Paetzold, Uwe U.; Mason, Paul H. (2016), The Fighting Art of Pencak Silat and its Music: From Southeast Asian Village to Global Movement, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-30874-9

- Hill, Robert (2010), World of Martial Arts, Lulu, ISBN 978-0557016631

- Sutton, Lian (2018), "Embodying the Elements within Nature through the traditional Malay art of Silat Tua", Tropical Imaginaries & Living Cities, eTropic: electronic journal of studies in the tropics, 17

- Pencak-Silat Panglipur Genève (2019), Alhaq - Grand Master Haji Hosni bin Ahmad

- Pertubuhan Silat Seni Gayong (2016), Main Page

- Sejarah Silat Melayu by Anuar Abd. Wahab (2006) in "Martabat Silat Warisan Negara, Keaslian Budaya Membina Bangsa" PESAKA (2006).

- Istilah Silat by Anuar Abd. Wahab (2006) in "Martabat Silat Warisan Negara, Keaslian Budaya Membina Bangsa" PESAKA (2006).

- Silat Dinobatkan Seni Beladiri Terbaik by Pendita Anuar Abd. Wahab AMN (2007) in SENI BELADIRI (June 2007)

- Silat itu Satu & Sempurna by Pendita Anuar Abd. Wahab AMN (2007) in SENI BELADIRI (September 2007)

External links

- Silat Melayu News Martial Arts Community Malaysia

- Culture Silat (French)