Shivaram Rajguru

Hutatma Shivaram Hari Rajguru (24 August 1908 – 23 March 1931)[1][2] was an Indian revolutionary from Maharashtra, known mainly for his involvement in the assassination of a British Raj police officer.He also fought for the independence of India and On 23 March 1931 he was hanged by the British government along with Bhagat Singh and Sukhdev Thapar.

Hutatma Shivaram Hari Rajguru | |

|---|---|

Rajguru on a 2013 stamp of India | |

| Born | 24 August 1908 |

| Died | 23 March 1931 (aged 22) |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Occupation | Indian freedom fighter |

| Organization | HSRA |

| Movement | Indian Independence movement |

Early life

Rajguru was born on 24 August 1908 at Khed to Parvati Devi and Harinarain Rajguru in a Marathi Brahmin family[3]. Khed was located at the bank of river Bheema near Poona (present-day Pune). His father died when he was only six years old and the responsibility of family fell on his elder brother Dinkar. He received primary education at Khed and later studied in New English High School in Poona.[1]

Revolutionary activities

He was a member of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association, who wanted India to be free from British rule by any means necessary.[2]

Rajguru became a colleague of Bhagat Singh and Sukhdev, and took part in the assassination of a British police officer, J. P. Saunders, at Lahore in 1928. Their actions were to avenge the death of Lala Lajpat Rai who had died a fortnight after being hit by police while on a march protesting the Simon Commission.[2] The feeling was that Rai's death resulted from the police action, although he had addressed a meeting later.[4][5]

The three men and 21 other co-conspirators were tried under the provisions of a regulation that was introduced in 1930 specifically for that purpose.[6] All three were convicted of the charges.

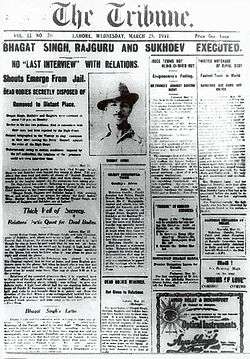

Executions

Scheduled for hanging on 24 March, three freedom fighters were hanged a day earlier on 23 March 1931. They were cremated at Hussainiwala at the banks of the Sutlej river in the Ferozepur district of Punjab.[7][1]

Reactions to the executions

The executions were reported widely by the press, especially as they took place on the eve of the annual convention of the Congress party at Karachi.[8] The New York Times reported:

A reign of terror in the city of Cawnpore in the United Provinces and an attack on Mahatma Gandhi by a youth outside Karachi were among the answers of the Indian extremists today to the hanging of Bhagat Singh and two fellow-assassins.[9]

Legacy and memorials

National Martyrs Memorial

National Memorial is located at Hussainiwala, in Ferozepur district of Punjab in India. After execution in Lahore jail, the bodies of Shivaram Rajguru, Bhagat Singh and Sukhdev Thapar were brought here in secrecy and they were unceremonially cremated here by authorities. Every year on 23 March, martyrs day (Shaheed Diwas) is observed remembering three revolutionaries. Tributes and homage is paid at the memorial.[10][7]

Rajgurunagar

His birthplace of Khed was renamed as Rajgurunagar in his honour.[2] Rajgurunagar is a census town in Khed tehsil of Pune district in state of Maharashtra.[11]

Rajguru Wada

Rajguru Wada is the ancestral house where Rajguru was born. Spread over 2,788 sq m of land, it is located on the banks of Bhima river on Pune-Nashik Road. It is being maintained as a memorial to Shivaram Rajguru. A local organisation, the Hutatma Rajguru Smarak Samiti (HRSS), hoists the national flag here on Republic Day since 2004.[12]

College

Shaheed Rajguru College of Applied Sciences for Women is located in Vasundhara Enclave, Delhi, and is a constituent college of Delhi University.[13]

Gallery

- Birth room of Hutatma Rajguru

- Rajguru, Bhagat Singh letters

- Rajguru Wada museum

See also

- Ashfaqulla Khan

- Kakori Train Robbery

- Thakur Roshan Singh

- Batukeshwar Dutt

References

- Verma, Anil (15 September 2017). RAJGURU – THE INVINCIBLE REVOLUTIONARY. Publications Division Ministry of Information & Broadcasting. ISBN 978-81-230-2522-3.

- "Remembering Shivaram Hari Rajguru on his birthday". India Today. 24 August 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "Bhagat Singh a 'Jat', Rajguru 'Brahmin'". Zee News. 12 April 2011. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Sawhney, Simona (2012). "Bhagat Singh: A Politics of Death and Hope". In Malhotra, Anshu; Mir, Farina (eds.). Punjab Reconsidered: History, Culture, and Practice. Oxford University Press. p. 380. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198078012.003.0054. ISBN 978-0-19807-801-2.

- Nair, Neeti (May 2009). "Bhagat Singh as 'Satyagrahi': The Limits to Non-violence in Late Colonial India". Modern Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 43 (3): 649–681. doi:10.1017/s0026749x08003491. JSTOR 20488099.

- Dam, Shubhankar (2013). Presidential Legislation in India: The Law and Practice of Ordinances. Cambridge University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-10772-953-7.

- "National Martyrs Memorial Hussainiwala". Firozepur district official website. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- "Bhagat "Indian executions stun the Congress". The New York Times. 25 March 1931. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- "Bhagat "50 die in India riot; Gandhi assaulted as party gathers". The New York Times. 26 March 1931. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- "Five decades on, heritage status eludes Hussainiwala memorial". The Tribune India. 27 September 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "Rajgurunagar Population Census 2011". 2011 Census of India. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "Freedom fighter Rajguru's wada". DNA India. 21 September 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- "Shaheed Rajguru College of Applied Sciences for Women". Official website of college. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

Further reading

- Noorani, Abdul Gafoor Abdul Majeed (2001) [1996]. The Trial of Bhagat Singh: Politics of Justice. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195796675.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shivaram Rajguru. |