Shapur I

Shapur I (also spelled Shabuhr I; Middle Persian: 𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩; New Persian: شاپور), also known as Shapur the Great, was the second Sasanian King of Kings of Iran. The dating of his reign is disputed, but it is generally agreed that he ruled from 240 to 270, with his father Ardashir I as co-regent till the death of the latter in 242. Shapur consolidated and expanded the empire of Ardashir I, waged war against the Roman Empire and seized its cities of Nisibis and Carrhae while he was advancing as far as Roman Syria. He was defeated at the Battle of Resaena in 243 but won the Battle of Misiche in 244 and forced Roman Emperor Philip the Arab to sign a favorable peace treaty the following year that was regarded by the Romans as "a most shameful treaty".[1]

| Shapur I 𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩 | |

|---|---|

| King of Kings of Iranians and non-Iranians[lower-alpha 2] | |

Reconstruction of the Colossal Statue of Shapur I by George Rawlinson, 1876 | |

| Shahanshah of the Sasanian Empire | |

| Reign | 12 April 240 – May 270 |

| Predecessor | Ardashir I |

| Successor | Hormizd I |

| Died | May 270 Bishapur |

| Consort | Khwarranzem al-Nadirah (?) |

| Issue | Bahram I Shapur Mishanshah Hormizd I Narseh Shapurdukhtak Adur-Anahid |

| House | House of Sasan |

| Father | Ardashir I |

| Mother | Denag |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

He took advantage of the political turmoil within the Roman Empire by undertaking a second expedition against it in 252/3–256 and sacking the cities of Antioch and Dura-Europos. In 260, during his third campaign, he defeated and captured the Roman emperor, Valerian, at the Battle of Edessa. However, he was less successful in his later endeavours and suffered setbacks by the king of Palmyra, Odaenathus.

Shapur was the first Iranian monarch to use the title of "King of Kings of Iranians and non-Iranians"; beforehand the royal titulary had been "King of Kings of Iranians". He had adopted the title due to the influx of Roman citizens whom he had deported during his campaigns. However, it was first under his son and successor Hormizd I, that the title became regularized. Shapur had new Zoroastrian fire temples constructed, incorporated new elements into the faith from Greek and Indian sources, and conducted an extensive program of rebuilding and refounding of cities.

Etymology

"Shapur" was a popular name in Sasanian Iran, being used by three Sasanian monarchs and several notables of the Sasanian era and its later periods. The name is derived from Old Iranian *xšayaθiya.puθra ("son of a king") and initially must have been a title, which became−at least in the late 2nd century AD, a personal name.[1] The name appears in the list of Arsacid kings in some Arabic-Persian sources, however, this is anachronistic.[1] The name of Shapur is known in other languages as; Greek Sapur, Sabour and Sapuris; Latin Sapores and Sapor; Arabic Sābur and Šābur; New Persian Šāpur, Šāhpur, Šahfur.[1]

Early years

Shapur was the son of Ardashir I (r. 224–242 [died 242]), the founder of the Sasanian dynasty and whom Shapur succeeded. His mother was Lady Myrōd,[2] who, according to legend,[3] was an Arsacid princess, a daughter of Artabanus IV.[4] The Talmud cites a nickname for her, "Ifra Hurmiz", after her bewitching beauty.[5] Shapur also had a brother named Ardashir, who would later serve as governor of Kirman. Shapur may have also had another brother with the same name, who served as governor of Adiabene.

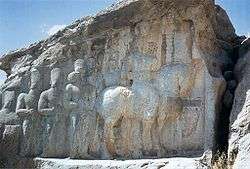

Shapur, as portrayed in the Sasanian rock reliefs, took part in his father's war with the Arsacids, including the Battle of Hormozdgan.[1] The battle was fought on 28 April 224, with Artabanus IV being defeated and killed, marking the end of the Arsacid era and the start of 427-years of Sasanian rule.[6] The chief secretary of the deceased Arsacid king, Dad-windad, was afterwards executed by Ardashir I.[7] Ardashir celebrated his victory by having two rock reliefs sculptured at the Sasanian royal city of Ardashir-Khwarrah (present-day Firuzabad) in Pars.[8][9] The first relief portrays three scenes of personal fighting; starting from the left, a Persian aristocrat seizing a Parthian soldier; Shapur impaling the Parthian minister Dad-windad with his lance; and Ardashir I ousting Artabanus IV.[9][6] The second relief, conceivably intended to portray the aftermath of the battle, displays the triumphant Ardashir I being given the badge of kingship over a fire shrine from the Zoroastrian supreme god Ahura Mazda, while Shapur and two other princes are watching from behind.[9][8] Ardashir considered Shapur "the gentlest, wisest, bravest and ablest of all his children", and nominated him as his successor in a council amongst the magnates.[1]

The Iranian historian Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari observed of Shapur before his ascension to the Sasanian throne:, "The Iranians had well-tried Shapur already before his accession and while his father still lived on account of his intelligence, understanding and learning as well as his outstanding boldness, oratory, logic, affection for the subject of people and kindheartedness." The Cologne Mani-Codex indicates that, by 240, Ardashir and Shapur were already reigning together.[2] In a letter from the Roman Emperor Gordian III to his senate, dated to 242, the "Persian Kings" are referred to in the plural. Synarchy is also evident in the coins of this period that portray Ardashir facing his youthful son and bear a legend that indicates Shapur as king.

The date of Shapur's coronation remains debated: 240 is frequently noted,[2] but Ardashir lived probably until 242.[10] The year 240 also marks the seizure and subsequent destruction of Hatra, about 100 km southwest of Nineveh and Mosul in present-day Iraq. According to legend, al-Nadirah, the daughter of the king of Hatra, betrayed her city to the Sasanians, who then killed the king and had the city razed. (Legends also have Shapur either marrying al-Nadirah, or having her killed, or both.)[11]

Military career

The Eastern Front

The Eastern provinces of the fledgling Sasanian Empire bordered on the land of the Kushans and the land of the Sakas (roughly today's Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan). The military operations of Shapur's father Ardashir I had led to the local Kushan and Saka kings offering tribute, and satisfied by this show of submission, Ardashir seems to have refrained from occupying their territories. Al-Tabari alleges he rebuilt the ancient city of Zrang in Sakastan (the land of the Sakas, Sistan), but the only early Sasanian period founding of a new settlement in the East of which we are certain is the building by Shapur I of Nishapur - “Beautifull (city built) by Shapur” - in Dihistan (former Parthia, apparently lost by the Parthians to the Kushans).[12]

Soon after the death of his father in 241 CE, Shapur felt the need to cut short the campaign they had started in Roman Syria, and reassert Sasanian authority in the East, perhaps because the Kushan and Saka kings were lax in abiding to their tributary status. However, he first had to fight “The Medes of the Mountains” - as we will see possibly in the mountain range of Gilan on the Caspian coast - and after subjugating them, he appointed his son Bahram (the later Bahram I) as their king. He then marched to the East and annexed most of the land of the Kushans, and appointing his son Narseh as Sakanshah - king of the Sakas - in Sistan. Shapur could now proudly proclaim that his empire stretched all the way to Peshawar, and his relief in Rag-i-Bibi in present-day Afghanistan confirms this claim.[13] Shapur I claims in his Naqsh-e Rostam inscription possession of the territory of the Kushans (Kūšān šahr) as far as "Purushapura" (Peshawar), suggesting he controlled Bactria and areas as far as the Hindu-Kush or even south of it:[14]

I, the Mazda-worshipping lord, Shapur, king of kings of Iran and An-Iran… (I) am the Master of the Domain of Iran (Ērānšahr) and possess the territory of Persis, Parthian… Hindestan, the Domain of the Kushan up to the limits of Paškabur and up to Kash, Sughd, and Chachestan.

He seems to have garrisoned the Eastern territories with POW's from his previous campaign against the Medes of the Mountains. Agathias claims Bahram II (274-293 CE) later campaigned in the land of the Sakas and appointed his brother Hormizd as its king. When Hormizd revolted, the Panegyrici Latini list his forces as the Sacci (Sakas), the Rufii (Cusii/Kushans) and the Geli (Gelans / Gilaks, the inhabitants of Gilan). Since the Gilaks are obviously out of place among these easterners, and as we know that Shapur I had to fight the Medes of the Mountains first before marching to the land of the Kushans, it is conceivable those Gilaks were the descendants of warriors captured during Shapur I's North-western campaign, forcibly drafted into the Sasanian army, and settled as a hereditary garrison in Merv, Nishapur, or Zrang after the conclusion of Shapur's north-eastern campaign, the usual Sasanian practise with prisoners of war.[15]

First Roman war

Ardashir I had, towards the end of his reign, renewed the war against the Roman Empire, and Shapur I had conquered the Mesopotamian fortresses Nisibis and Carrhae and had advanced into Syria. In 242, the Romans under the father-in-law of their child-emperor Gordian III set out against the Sasanians with "a huge army and great quantity of gold," (according to a Sasanian rock relief) and wintered in Antioch, while Shapur was occupied with subduing Gilan, Khorasan, and Sistan.[16] There the Roman general Timesitheus fought against the Sasanians and won repeated battles, and recaptured Carrhae and Nisibis, and at last routed a Sasanian army at Resaena, forcing the Persians to restore all occupied cities unharmed to their citizens. “We have penetrated as far as Nisibis, and shall even get to Ctesiphon," the young emperor Gordian III, who had joined his father-in-law Timesitheus, exultantly wrote to the Senate.

The Romans later invaded eastern Mesopotamia but faced tough resistance from Shapur I returned from the East. Timesitheus died under uncertain circumstances and was succeeded by Philip the Arab. The young emperor Gordian III went to the Battle of Misiche and was either killed in the battle or murdered by the Romans after the defeat. The Romans then chose Philip the Arab as Emperor. Philip was not willing to repeat the mistakes of previous claimants, and was aware that he had to return to Rome to secure his position with the Senate. Philip concluded a peace with Shapur I in 244; he had agreed that Armenia lay within Persia's sphere of influence. He also had to pay an enormous indemnity to the Persians of 500,000 gold denarii.[17] Philip immediately issued coins proclaiming that he had made peace with the Persians (pax fundata cum Persis).[18] However, Philip later broke the treaty and seized lost territory.[17]

Shapur I commemorated this victory on several rock reliefs in Pars.

Second Roman war

Shapur I invaded Mesopotamia in 250 but again, serious trouble arose in Khorasan and Shapur I had to march over there and settle its affair. Having settled the affair in Khorasan he resumed the invasion of Roman territories, and later annihilated a Roman force of 60,000 at the Battle of Barbalissos. He then burned and ravaged the Roman province of Syria and all its dependencies.

Shapur I then reconquered Armenia, and incited Anak the Parthian to murder the king of Armenia, Khosrov II. Anak did as Shapur asked, and had Khosrov murdered in 252; yet Anak himself was shortly thereafter murdered by Armenian nobles.[19] Shapur then appointed his son Hormizd I as the "Great King of Armenia". With Armenia subjugated, Georgia submitted to the Sasanian Empire and fell under the supervision of a Sasanian official.[17] With Georgia and Armenia under control, the Sasanians' borders on the north were thus secured.

During Shapur's invasion of Syria he captured important Roman cities like Antioch. The Emperor Valerian (253–260) marched against him and by 257 Valerian had recovered Antioch and returned the province of Syria to Roman control. The speedy retreat of Shapur's troops caused Valerian to pursue the Persians to Edessa, but they were defeated by the Persians, and Valerian, along with the Roman army that was left, was captured by Shapur[18] and sent away into Pars. Shapur then advanced into Asia Minor and managed to capture Caesarea, deporting 400,000 of its citizens to the southern Sasanian provinces.

The victory over Valerian is presented in a mural at Naqsh-e Rustam, where Shapur is represented on horseback wearing royal armour and a crown. Before him kneels a man in Roman dress, asking for grace. The same scene is repeated in other rock-face inscriptions.[20] Christian tradition has Shapur I humiliating Valerian, infamous for his persecution of Christians, by the King of Kings using the Emperor as a foot-stool to mount his horse, and they claim he later died a miserable death in captivity at the hands of the enemy. However, just as with the above-mentioned Gilaks deported to the East by Shapur, the Persian treatment of POWs was unpleasant but honourable, drafting the captured Romans and their Emperor into their army and deporting them to a remote place, Bishapur in Khuzistan, were they were settled as a garrison and built a weir with bridge for Shapur.[21]

However, the Persian forces were later defeated by the Roman officer Balista and the lord of Palmyra Septimius Odenathus, who captured the royal harem. Shapur plundered the eastern borders of Syria and returned to Ctesiphon, probably in late 260.[17] In 264 Septimius Odenathus reached Ctesiphon, but was defeated by Shapur I.[22][23][24]

The Colossal Statue of Shapur I, which stands in the Shapur Cave, is one of the most impressive sculptures of the Sasanian Empire.

Interactions with minorities

Shapur is mentioned many times in the Talmud, in which he is referred to in Jewish Aramaic as Shabur Malka (שבור מלכא), meaning "King Shabur". He had good relations with the Jewish community and was a friend of Shmuel, one of the most famous of the Babylonian Amoraim, the Talmudic sages from among the important Jewish communities of Mesopotamia.

Roman prisoners of war

Shapur's campaigns deprived the Roman Empire of resources while restoring and substantially enriching his own treasury, by deporting many Romans from conquered cities to Sasanian provinces like Khuzestan, Asuristan, and Pars. This influx of deported artisans and skilled workers revitalized Iran's domestic commerce.[1]

Death

In Bishapur, Shapur died of an illness. His death came in May 270 and he was succeeded by his son, Hormizd I. Two of his other sons, Bahram I and Narseh, would also become kings of the Sasanian Empire; while another son, Shapur Meshanshah, who died before Shapur, sired children who would hold exalted positions within the empire.[1]

Government

Governors during his reign

Under Shapur, the Sasanian court, including its territories, were much larger than that of his father. Several governors and vassal-kings are mentioned in his inscriptions; Ardashir, governor of Qom; Varzin, governor of Spahan; Tiyanik, governor of Hamadan; Ardashir, governor of Neriz; Narseh, governor of Rind; Friyek, governor of Gundishapur; Rastak, governor of Veh-Ardashir; Amazasp III, king of Iberia. Under Shapur several of his relatives and sons served as governor of Sasanian provinces; Bahram, governor of Gilan; Narseh, governor of Sindh, Sakastan and Turan; Ardashir, governor of Kirman; Hormizd-Ardashir, governor of Armenia; Shapur Meshanshah, governor of Meshan; Ardashir, governor of Adiabene.[25]

Officials during his reign

Several names of Shapur's officials are carved on his inscription at Naqsh-e Rustam. Many of these were the offspring of the officials who served Shapur's father. During the reign of Shapur, a certain Papak served as the commander of the royal guard (hazarbed), while Peroz served as the chief of the cavalry (aspbed); Vahunam and Shapur served as the director of the clergy; Kirdisro served as viceroy of the empire (bidaxsh); Vardbad served as the "chief of services"; Hormizd served as the chief scribe; Naduk served as "the chief of the prison"; Papak served as the "gate keeper"; Mihrkhwast served as the treasurer; Shapur served as the commander of the army; Arshtat Mihran served as the secretary; Zik served as the "master of ceremonies".[26]

Army

Under Shapur, the Iranian military experienced a resurge after a rather long decline in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, which gave the Romans the opportunity to undertake expeditions into the Near East and Mesopotamia during the end of the Parthian Empire.[27] Yet, the military was essentially the same as that of the Parthians; the same Parthians nobles who served the Arsacid royal family, now served the Sasanians, forming the majority of the Sasanian army.[28] However, the Sasanians seem to have employed more cataphracts who were equipped with lighter chain-mail armor resembling that of the Romans.[28]

Although Iranian society was greatly militarised and its elite designated themselves as a "warrior nobility" (arteshtaran), it still had a significantly smaller population, was more impoverished, and was a less centralized state compared to the Roman Empire.[28] As a result, the Sasanian shahs had access to fewer full-time fighters, and depended on recruits from the nobility instead.[28] Some exceptions were the royal cavalry bodyguard, garrison soldiers, and units recruited from places outside Iran.[28] The bulk of the nobility included the powerful Parthian noble families (known as the wuzurgan) that were centered on the Iranian plateau.[29] They served as the backbone of the Sasanian feudal army and were largely autonomous.[29] The Parthian nobility worked for the Sasanian shah for personal benefit, personal oath, and, conceivably, a common awareness of the "Aryan" (Iranian) kinship they shared with their Persian overlords.[29]

Use of war elephants is also attested under Shapur, who made use of them to demolish the city of Hatra.[30] He may also have used them against Valerian, as attested in the Shahnameh (The Book of Kings).[31]

Monuments

Shapur I left other reliefs and rock inscriptions. A relief at Naqsh-e Rajab near Estakhr is accompanied by a Greek translation. Here Shapur I calls himself "the Mazdayasnian (worshipper of Ahuramazda), the divine Shapur, King of Kings of the Iranians, and non-Iranians, of divine descent, son of the Mazdayasnian, the divine Ardashir, King of Kings of the Aryans, grandson of the divine king Papak". Another long inscription at Estakhr mentions the King's exploits in archery in the presence of his nobles.

From his titles we learn that Shapur I claimed sovereignty over the whole earth, although in reality his domain extended little farther than that of Ardashir I. Shapur I built the great town Gundishapur near the old Achaemenid capital Susa, and increased the fertility of the district with a dam and irrigation system – built by Roman prisoners – that redirected part of the Karun River. The barrier is still called Band-e Kaisar, "the mole of the Caesar". He is also responsible for building the city of Bishapur, with the labours of Roman soldiers captured after the defeat of Valerian in 260. Shapur also built a town named Pushang in Khorasan.

Religious policy

Shapur on his coins and inscriptions calls himself a "worshiper of Mazda" the god of Zoroastrianism. In one of his inscriptions, he mentioned that he felt he had a mission to achieve in the world:

For the reason, therefore, that the gods have so made us their instrument, and that by the help of the gods we have sought out for ourselves, and hold, all these nations for that reason we have also founded, province by province, many Varahrān fires, and we have dealt piously with many Magi, and we have made great worship of the gods.

Shapur also wanted to add other writings to the Avesta, the holy book of Zoroastrianism, which included non-religious writings from Europe and India, about medicine, astronomy, philosophy and more.

The religious phenomenon shown by Shapur, shows that under his reign, the Zoroastrian clergy began to rise, as evidenced by the Mobed Kartir, who claims, in an inscription, that he took advantage of the conquests of Shapur to promote Zoroastrianism. Even though Kartir was part of the court of Shapur, the power of the clergy was limited, and only began to expand during the reign of Bahram I.

Shapur, who was never under the control of the clergy, appears as a particularly tolerant ruler, ensuring the best reception for representatives of all religions in his empire. Jewish sources have preserved him as a benevolent ruler that gave audiences to the leaders of their community. Later Greeks accounts writes about Shapur's invasion of Syria, where he destroyed everything except important religious sanctuaries of the cities. He also gave the Christians of his empire religious freedom, and allowed them to build churches without needing agreement from the Sasanian court.

During the reign of Shapur, Manichaeism, a new religion founded by the Iranian prophet Mani, flourished. Mani was treated well by Shapur, and in 242, the prophet joined the Sasanian court, where he tried to convert Shapur by dedicating his only work written in Middle Persian, known as the Shabuhragan. Shapur, however, did not convert to Manichaeanism and remained a Zoroastrian.[32]

Coinage and imperial ideology

While the titulage of Ardashir was "King of Kings of (Iran)ians", Shapur slighty changed it, adding the phrase "and non-Iran(ians)".[33] The extended title demonstrates the incorporation of new territory into the empire, however what was precisely seen as "non-Iran(ian)" (aneran) is not certain.[34] Although this new title was used on his inscriptions, it was almost never used on his coinage.[35] The title first became regularized under Hormizd I.[36]

In popular culture

.png)

Shapur appears in Harry Sidebottom's historical fiction novel series as one of the enemies of the series protagonist Marcus Clodius Ballista, career soldier in a third-century Roman army.

See also

- Shapour I's inscription in Ka'ba-ye Zartosht

- Shapour I's inscription in Naqsh-e Rostam

- Siege of Dura Europos (256)

Notes

- Also spelled "King of Kings of Iran and non-Iran".

- Also spelled "King of Kings of Iran and non-Iran".

References

- Shahbazi 2002.

- Shahbazi, Shapur (2003). "Shapur I". Encyclopedia Iranica. Costa Mesa: Mazda.

- Herzfeld, E. E. (1988). Iran in the Ancient East. New York: Hacker Art Books. ISBN 0-87817-308-0. p. 287.

- Iain Gardner, Jason D. Beduhn, Paul Dilley, Mani at the Court of the Persian Kings: Studies on the Chester Beatty Kephalaia Codex (2014), p. 86

- Talmud Bavli, Tractate Baba Basra 8a. See there note 56 in Artscroll edition(2004)

- Shahbazi 2004, pp. 469–470.

- Rajabzadeh 1993, pp. 534–539.

- Shahbazi 2005.

- McDonough 2013, p. 601.

- J. Wiesehöfer, Ardasir, in: Encyclopedia Iranica.

- "Hatra". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2008. Retrieved December 8, 2007.

- Thaalibi 485-6 even ascribes the founding of Badghis and Khwarazm to Ardashir I

- W. Soward, "The Inscription Of Shapur I At Naqsh-E Rustam In Fars", sasanika.org, 3. Cf. F. Grenet, J. Lee, P. Martinez, F. Ory, “The Sasanian Relief at Rag-i Bibi (Northern Afghanistan)” in G. Hermann, J. Cribb (ed.), After Alexander. Central Asia before Islam (London 2007), 259-60

- Rezakhani, Khodadad. From the Kushans to the Western Turks. pp. 202–203.

- Agathias 4.24.6-8; Panegyrici Latini N3.16.25; Thaalibi 495; Arthur Christensen, L'Iran sous les Sassanides (Copenhague 1944) 214

- Iranians in Asia Minor, Leo Raditsa, Cambridge History of Iran: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian periods, Vol. 3, ed. Ehsan Yarshater, (Cambridge University Press, 2003), 125.

- Shapur I, Shapur Shahbazi, Encyclopaedia Iranica, (July 20, 2002).

- Cambridge History of Iran, Volume III, edited by Ehsan Yarshater (professor of Iranian studies, Columbia University, New York)

- Hovannisian, The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century, p.72

- Grishman, R.(1995):Iran From the Beginning Until Islam

- Prof. A. Tafazzoll, (1990): History of Ancient Iran, pg. 183

- Who's Who in the Roman World By John Hazel

- Babylonia Judaica in the Talmudic Period By A'haron Oppenheimer, Benjamin H. Isaac, Michael Lecker

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica

- Frye 1984, p. 299.

- Frye 1984, p. 373.

- Daryaee & Rezakhani 2017, p. 157.

- McDonough 2013, p. 603.

- McDonough 2013, p. 604.

- Daryaee 2014, p. 46.

- Daryaee 2016, p. 37.

- Marco Frenschkowski (1993). "Mani (iran. Mānī<; gr. Mανιχαῑος < ostaram. Mānī ḥayyā "der lebendige Mani")". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). 5. Herzberg: Bautz. cols. 669–80. ISBN 3-88309-043-3.

- Shayegan 2013, p. 805.

- Shayegan 2004, pp. 462-464.

- Curtis & Stewart 2008, pp. 21, 23.

- Curtis & Stewart 2008, p. 21.

Sources

- Al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir (1985–2007). Ehsan Yar-Shater (ed.). The History of Al-Ṭabarī. 40 vols. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brosius, Maria (2000). "Women i. In Pre-Islamic Persia". Encyclopaedia Iranica. London et al.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Stewart, Sarah (2008). The Sasanian Era. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–200. ISBN 9780857719720.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–240. ISBN 978-0857716668.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daryaee, Touraj (2010). "Ardashir and the Sasanians' Rise to Power". University of California: 236–255. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daryaee, Touraj (2016). "From Terror to Tactical Usage: Elephants in the Partho-Sasanian Period". In Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Pendleton, Elizabeth J.; Alram, Michael; Daryaee, Touraj (eds.). The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: Adaptation and Expansion. Oxbow Books. ISBN 9781785702082.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daryaee, Touraj; Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). "The Sasanian Empire". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE - 651 CE). UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies. pp. 1–236. ISBN 9780692864401.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daryaee, Touraj (2018). "Res Gestae Divi Saporis". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H.Beck. pp. 1–411. ISBN 9783406093975.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gignoux, Ph. (1983). "Ādur-Anāhīd". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 5. London et al. p. 472.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gignoux, Philippe (1994). "Dēnag". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VII, Fasc. 3. p. 282.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kia, Mehrdad (2016). The Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610693912.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (2 volumes)

- McDonough, Scott (2011). "The Legs of the Throne: Kings, Elites, and Subjects in Sasanian Iran". In Arnason, Johann P.; Raaflaub, Kurt A. (eds.). The Roman Empire in Context: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 290–321. doi:10.1002/9781444390186.ch13. ISBN 9781444390186.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McDonough, Scott (2013). "Military and Society in Sasanian Iran". In Campbell, Brian; Tritle, Lawrence A. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Warfare in the Classical World. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–783. ISBN 9780195304657.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2016). "Dynastic Connections in the Arsacid Empire and the Origins of the House of Sāsān". In Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Pendleton, Elizabeth J.; Alram, Michael; Daryaee, Touraj (eds.). The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: Adaptation and Expansion. Oxbow Books. ISBN 9781785702082.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-645-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rajabzadeh, Hashem (1993). "Dabīr". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VI, Fasc. 5. pp. 534–539.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2014). The Sasanian World through Georgian Eyes: Caucasia and the Iranian Commonwealth in Late Antique Georgian Literature. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1472425522.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). "East Iran in Late Antiquity". ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–256. ISBN 9781474400305. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt1g04zr8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (registration required)

- Schindel, Nikolaus (2013). "Sasanian Coinage". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199733309.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schippmann, K. (1986a). "Artabanus (Arsacid kings)". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 6. pp. 647–650.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schippmann, K. (1986b). "Arsacids ii. The Arsacid dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 5. pp. 525–536.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schmitt, R. (1986). "Artaxerxes". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 6. pp. 654–655.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (1988). "Bahrām I". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 5. pp. 514–522.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2002). "Šāpur I". Encyclopaedia Iranica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2004). "Hormozdgān". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5. pp. 469–470.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2005). "Sasanian dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2004). "Hormozd I". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5. pp. 462–464.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2013). "Sasanian Political Ideology". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199733309.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skjærvø, Prods Oktor (2011). "Kartir". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XV, Fasc. 6. pp. 608–628.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stausberg, Michael; Vevaina, Yuhan Sohrab-Dinshaw; Tessmann, Anna (2015). The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vevaina, Yuhan; Canepa, Matthew (2018). "Ohrmazd". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weber, Ursula (2016). "Narseh". Encyclopaedia Iranica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (1986). "Ardašīr I i. History". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 4. pp. 371–376.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (2000b). "Frataraka". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. X, Fasc. 2. p. 195.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (2000a). "Fārs ii. History in the Pre-Islamic Period". Encyclopaedia Iranica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (2001). Ancient Persia. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1860646751.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (2009). "Persis, Kings of". Encyclopaedia Iranica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shapur I of Persia. |

Shapur I | ||

| Preceded by Ardashir I |

King of kings of Iran and non-Iran 240–270 |

Succeeded by Hormizd I |