Shah Mosque (Isfahan)

The Shah Mosque (Persian: مسجد شاه) is a mosque located in Isfahan, Iran. It is located on the south side of Naghsh-e Jahan Square. It was built during the Safavid dynasty under the order of Shah Abbas I of Persia. It was also known as the Imam Mosque after the Iranian Revolution.[2][3]

| Shah Mosque | |

|---|---|

مسجد شاه | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Shia Islam |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Isfahan, Iran |

| State | Isfahan Province |

Shown within Iran | |

| Geographic coordinates | 32°39′16″N 51°40′39″E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Ali Akbar Isfahani[1] |

| Style | Safavid Persian |

| Groundbreaking | 1611 |

| Completed | 1629 |

| Construction cost | 20,000 tomans |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 100m |

| Width | 130m |

| Height (max) | 56m with golden shaft |

| Dome(s) | 3 |

| Dome height (outer) | 53 m |

| Dome height (inner) | 38m |

| Dome dia. (outer) | 25 |

| Dome dia. (inner) | 23 |

| Minaret(s) | 4 |

| Minaret height | 48 m |

It is regarded as one of the masterpieces of Persian architecture in the Islamic era. The Royal Mosque is registered, along with the Naghsh-e Jahan Square, as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[4] Its construction began in 1611, and its splendour is mainly due to the beauty of its seven-colour mosaic tiles and calligraphic inscriptions.

The mosque is depicted on the reverse of the Iranian 20,000 rials banknote.[5]

History

In 1598, when Shah Abbas decided to move the capital of his Persian empire from the northwestern city of Qazvin to the central city of Isfahan, he initiated what would become one of the greatest programmes in Persian history; the complete remaking of this ancient city. By choosing the central city of Isfahan, fertilized by the Zāyandeh River ("The life-giving river"), lying as an oasis of intense cultivation in the midst of a vast area of arid landscape, he both distanced his capital from any future assaults by Iran's neighboring arch rival, the Ottomans, and at the same time gained more control over the Persian Gulf, which had recently become an important trading route for the Dutch and British East India Companies.[6]

The chief architect of this task of urban planning was Shaykh Bahai (Baha' ad-Din al-`Amili), who focused the programme on two key features of Shah Abbas's master plan: the Chahar Bagh avenue, flanked at either side by all the prominent institutions of the city, such as the residences of all foreign dignitaries, and the Naqsh-e Jahan Square ("Exemplar of the World").[7] Prior to the Shah's ascent to power, Persia had a decentralized power structure, in which different institutions battled for power, including both the military (the Qizilbash) and governors of the different provinces making up the empire. Shah Abbas wanted to undermine this political structure, and the recreation of Isfahan, as a Grand capital of Persia, was an important step in centralizing the power.[8] The ingenuity of the square, or Maidān, was that, by building it, Shah Abbas would gather the three main components of power in Persia in his own backyard; the power of the clergy, represented by the Masjed-e Shah, the power of the merchants, represented by the Imperial Bazaar, and of course, the power of the Shah himself, residing in the Ali Qapu Palace.

The crown jewel in this project was the Masjed i Shah, which would replace the much older Jameh Mosque in conducting the Friday prayers. To achieve this, the Shah Mosque was constructed not only with vision of grandeur, having the largest dome in the city, but Shaykh Bahai also planned the construction of two religious schools and a winter mosque clamped at either side of it.[9] Because of the Shah's desire to have the building completed during his lifetime, shortcuts were taken in the construction; for example, the Shah ignored warnings by one of the architects Abu'l Qāsim regarding the danger of subsidence in the foundations of the mosque, and he pressed ahead with the construction.[10] The architect proved to have been justified, as in 1662 the building had to undergo major repairs.[11] Also, the Persians decorated the mosque with the Seven-colored wall tiles that was both cheaper and quicker, and that eventually sped up the construction. This job was done by some of the best craftsmen in the country, and the whole work was supervised by Master calligrapher, Reza Abbasi. In the end, the final touches on the mosque were made in late 1629, A few months after the death of the Shah.

Also, many historians have wondered about the peculiar orientation of The Royal square (The Maidān). Unlike most buildings of importance, this square did not lie in alignment with Mecca, so that when entering the entrance-portal of the mosque, one makes, almost without realising it, the half-right turn, which enables the main court within to face Mecca. Donald Wilber gives the most plausible explanation to this; the vision of Shaykh Bahai was for the mosque to be visible wherever in the maydān a person was situated. Had the axis of the maydān coincided with the axis of Mecca, the dome of the mosque would have been concealed from view by the towering entrance portal leading to it. By creating an angle between them, the two parts of the building, the entrance portal and the dome, are in perfect view for everyone within the square to admire.[12]

Architecture and design

Design – the four-iwan style

The Safavids founded the Shah Mosque as a channel through which they could express themselves with their numerous architectural techniques. The four-iwan format, finalized by the Seljuq dynasty, and inherited by the Safavids, firmly established the courtyard facade of such mosques, with the towering gateways at every side, as more important than the actual building itself.[13] During Seljuq rule, as Islamic mysticism was on the rise and Persians were looking for a new type of architectural design that emphasized a Persian identity, the four-iwan arrangement took form. The Persians already had a rich architectural legacy, and the distinct shape of the iwan was actually taken from earlier, Sassanid palace-designs,[13] such as The Palace of Ardashir. Thus, Islamic architecture witnessed the emergence of a new brand that differed from the hypostyle design of the early, Arab mosques, such as the Umayyad Mosque. The four-iwan format typically took the form of a square shaped, central courtyard with large entrances at each side, giving the impression of being gateways to the spiritual world.

.jpg)

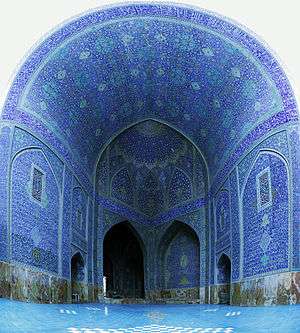

Standing in the public square, or Maidan, the entrance-iwan (gateway) to the mosque takes the form of a semicircle, resembling a recessed half-moon and measuring 27 meters in height, the arch framed by turquoise ornament and decorated with rich stalactite-like tilework called muqarnas, a distinct feature of Persian Islamic architecture. At the sides rise two minarets, 42 meters high, topped by beautifully carved, wooden balconies with muqarnas running down the sides. Master calligrapher of the Royal court, Reza Abbasi, inscribed the date of the groundbreaking of the construction, and besides it, verses praising Muhammad and Ali.[14] In the middle, in front of the entrance, stood a small pool and a resting place for the horses, and inside the worshipers found a large marble basin set on a pedestal, filled with fresh water or lemonade. This basin still stands as it has for four hundred years, but no longer serves the function of providing refreshments to the worshipers at the Friday prayers.

When passing through the entrance portal, one reaches the main courtyard, centered around a large pool. The two gateways (iwans) on the sides leads ones attention to the main gateway at the far end, the only one with minarets, and behind it the lofty dome, with its colorful ornamentation.

The distinct feature of any mosque is the minaret, and the Masjed-e Shah has four. Still, in Persian mosques, tall minarets were considered unsuitable for the call to prayer, and they would add an aedicule, known in Persian as a goldast (bouquet) for this particular purpose, which in the Masjed-e Shah stands on top of the west iwan.[15]

Religious buildings

Inside, the acoustic properties and reflections at the central point under the dome is an amusing interest for many visitors, as the ingenuity of the architects, when creating the dome, enables the Imam to speak with a subdued voice and still be heard clearly by everyone inside the building.

The mihrab, a large marble tablet ten feet tall and three feet wide on the southwestern wall, indicated the direction of Mecca. Above it the Shah's men had placed a gold-encrusted cupboard of allow wood. It held two relics: a Quran, said to have been copied by Imam Reza, and the bloodstained robe of Imam Hussain. Although never displayed, the robe was said to have magical powers; lifted on the end of a pike in the battle field, the belief was that it could rout an enemy.[16]

From the main courtyard, the iwan pointing to east contained a religious school, or madrasa. It contains an inscription by calligrapher Muhammad Riza Imami praising the Fourteen Immaculate Ones (i.e., Muhammad, Fatimah and The Twelve Imams). The iwan in the western corner leads to another madrasa and a winter mosque. In its own, private courtyard, one can find the famous sundial made by Shaykh Bahai.

The dome

After the introduction of domes into Islamic architectural designs by Arabs during the 7th century, domes appeared frequently in the architecture of mosques. The oldest Persian building containing a dome is the Grand Mosque of Zavareh, dating 1135.[17] The Persians had constructed such domes for centuries before, and some of the earliest known examples of large-scale domes in the World are found in Iran, an example being the Maiden Castle. So, the Safavid Muslims borrowed heavily from pre-Islamic knowledge in dome-building, i.e. the use of squinches to create a transition from an octagonal structure, into a circular dome. To cover up these transition zones, the Persians built rich networks of muqarnas. Thus, came also the introduction of this feature into Persian mosques.

A renaissance in Persian dome building was initiated by the Safavids. The distinct feature of Persian domes, which separates them from those domes created in the Christian world or the Ottoman and Mughal empires, was the colorful tiles, with which they covered the exterior of their domes, as they would on the interior. These domes soon numbered dozens in Isfahan, and the distinct, blue-colored shape would dominate the skyline of the city. Reflecting the light of the sun, these domes appeared like glittering turquoise gem and could be seen from miles away by travelers following the Silk road through Persia. Reaching 53 meters in height, the dome of the Masjed-e Shah would become the tallest in the city when it was finished in 1629. It was built as a double-shelled dome, with 14 meters spanning between the two layers, and resting on an octagonal dome chamber.[18]

Art

The Masjed-e Shah was a huge structure, said to contain 18 million bricks and 475,000 tiles, having cost the Shah 60,000 tomans to build.[19] It employed the new haft rangi (seven-colour) style of tile mosaic. In earlier Iranian mosques the tiles had been made of faience mosaic, a slow and expensive process where tiny pieces are cut from monochrome tiles and assembled to create intricate designs. In the haft rangi method, artisans put on all the colors at once, then fired the tile. Cheaper and quicker, the new procedure allowed a wider range of colors to be used, creating richer patterns, sweeter to the eye.[11][20] According to Jean Chardin, it was the low humidity in the air in Persia that made the colors so much more vivid and the contrasts between the different patterns so much stronger than what could be achieved in Europe, where the colors of tiles turned dull and lost its appearance.[21] Still, most contemporary and modern writers regard the tile work of the Masjed-e Shah as inferior in both quality and beauty compared to those covering the Lotfallah Mosque, the latter often referred to by contemporary Persian historians, such as Iskandar Munshi, as the mosque of great purity and beauty.[22] The architects also employed a great deal of marble, which they gathered from a marble quarry in nearby Ardestan.[11] Throughout the building, from the entrance portal and to the main building, the lower two meters of the walls are covered with beige marble, with beautifully carved poles at each side of every doorway and carved inscriptions throughout. Above this level begins the mosaic tiles that cover the rest of the building.

The entrance portal of the mosque displays the finest tile decoration in the building. It is entirely executed in tile mosaic in a full palette of seven colors (dark Persian blue, light Turkish blue, white, black, yellow, green and bisquit). A wide inscription band with religious texts written in white thuluth script on a dark blue ground frames the iwan. The tiles in the Masjed-e Shah are predominantly blue, except in the covered halls of the building, which were later revetted in tiles of cooler, yellowy-green shades.[20]

Facing northwards, the mosque's portal to the Maidan is usually under shadow but since it has been coated with radiant tile mosaics it glitters with a predominantly blue light of extraordinary intensity. The ornamentation of the structures is utterly traditional, as it recaptures the classic Iranian motifs of symbolic appeal for fruitfulness and effectiveness. Within the symmetrical arcades and the balanced iwans, one is drowned by the endless waves of intricate arabesque in golden yellow and dark blue, which bless the spectator with a space of internal serenity.

Architects

The architect of the mosque is Ali Akbar Isfahani. His name appears in an inscription in the mosque above the doorway of the entrance iwan complex. The inscription also mentions that the supervisor of the construction as Muhibb 'Ali Beg Lala who was also a major donor to the mosque. Another architect Badi al-zaman-i Tuni may have been involved in its early design.[1]

Measurements

The port of the mosque measures 27 m (89 ft) high, crowned with two minarets 42 m (138 ft) tall. The Mosque is surrounded with four iwans and arcades. All the walls are ornamented with seven-color mosaic tile. The most magnificent iwan of the mosque is the one facing the Qibla measuring 33 m (108 ft) high. Behind this iwan is a space which is roofed with the largest dome in the city at 53 m (174 ft) height. The dome is double layered. The whole of the construction measures 100 by 130 metres (330 ft × 430 ft), with the central courtyard measuring 70 by 70 metres (230 ft × 230 ft).

Photo gallery

- The mosque at night

- Facade of entrance arcade

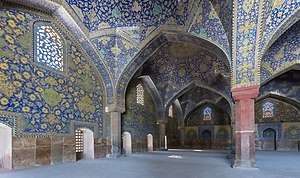

The interior of the main building

The interior of the main building- Peculiar orientation of the mosque in relation to the square

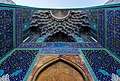

Bottom view of the iwan of the main entrance

Bottom view of the iwan of the main entrance Detail of the entrance

Detail of the entrance

See also

Notes

- Kishwar Rizvi (ed.). Affect, Emotion, and Subjectivity in Early Modern Muslim Empires. Brill. pp. 29–30. ISBN 9789004352841.

- Blake, Stephen P.; Half the World. The Social Architecture of Safavid Isfahan, 1590–1722, pp. 117–9.

- Sussan Babaie, Talinn Grigor, eds. (30 June 2014). Persian Kingship and Architecture: Strategies of Power in Iran from the Achaemenids to the Pahlavis. I.B.Tauris. p. 187. ISBN 978-1848857513.CS1 maint: uses editors parameter (link)

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/115

- Central Bank of Iran. Banknotes & Coins: 20000 Rials. – Retrieved on 24 March 2009.

- Savory, Roger; Iran under the Safavids, p. 155.

- Sir Roger Stevens; The Land of the Great Sophy, p. 172.

- Savory; chpt: The Safavid empire at the height of its power under Shāh Abbas the Great (1588–1629)

- Blake, Stephen P.; Half the World, The Social Architecture of Safavid Isfahan, 1590–1722, p. 143–144.

- Savory, p. 162

- Blake; p. 144

- Wilber, Donald; Aspects of the Safavid Ensemble at Isfahan, in Iranian Studies VII: Studies on Isfahan Part II, p 407–408.

- http://www.ne.jp/asahi/arc/ind/2_meisaku/55_shah/sha_eng.htm

- Blake; p. 143

- Hattstein M., Delius P.; Islam, Art and Architecture; p. 513

- Blake, p. 143

- http://www.ne.jp/asahi/arc/ind/2_meisaku/50_zavareh/zav_eng.htm

- Hattstein M., Delius P.; p. 513–514

- Pope; Survey, p. 1185–88

- Hattstein M., Delius P.; p. 513

- Ferrier, R. W.; A Journey to Persia, Jean Chardin's Portrait of a Seventeenth-century Empire, chpt: Arts and Crafts

- Blake; p. 149

References

- Mimaran-i Iran by Zohreh Bozorg-nia. 2004. ISBN 964-7483-39-2

Further reading

- Half the World. The Social Architecture of Safavid Isfahan, 1590–1722; by Stephen P. Blake

- Iran Under the Safavids; by Roger Savory

- A journey to Persia. Jean Chardin's Portrait of a Seventeenth-century Empire; by R. W. Ferrier

- Iran: Empire of the Mind; by Michael Axworthy

- L. Golombek: ‘Anatomy of a Mosque: The Masjid-i Shāh of Iṣfahān’, Iranian Civilization and Culture, ed. C. J. Adams (Montreal, 1972), pp. 5–11

External links

- A Documentary on Isfahan's Royal Mosque (Produced by ARTE)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shah Mosque. |