Self-defense

Self-defense (self-defence in some varieties of English) is a countermeasure that involves defending the health and well-being of oneself from harm.[1] The use of the right of self-defense as a legal justification for the use of force in times of danger is available in many jurisdictions.[2]

Physical

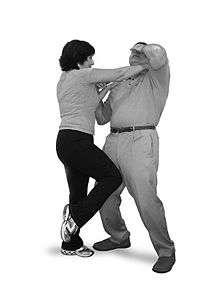

Physical self-defense is the use of physical force to counter an immediate threat of violence. Such force can be either armed or unarmed. In either case, the chances of success depend on various parameters, related to the severity of the threat on one hand, but also on the mental and physical preparedness of the defender.

Unarmed

Many styles of martial arts are practiced for self-defense or include self-defense techniques. Some styles train primarily for self-defense, while other martial or combat sports can be effectively applied for self-defense. Some martial arts train how to escape from a knife or gun situation, or how to break away from a punch, while others train how to attack. To provide more practical self-defense, many modern martial arts schools now use a combination of martial arts styles and techniques, and will often customize self-defense training to suit individual participants.

Armed

A wide variety of weapons can be used for self-defense. The most suitable depends on the threat presented, the victim or victims, and the experience of the defender. Legal restrictions also greatly influence self-defense options.

In many cases there are also legal restrictions. While in some jurisdictions firearms may be carried openly or concealed expressly for this purpose, many jurisdictions have tight restrictions on who can own firearms, and what types they can own. Knives, especially those categorized as switchblades may also be controlled, as may batons, pepper spray and personal stun guns and Tasers - although some may be legal to carry with a license or for certain professions.

Non-injurious water-based self-defense indelible dye-marker sprays, or ID-marker or DNA-marker sprays linking a suspect to a crime scene, would in most places be legal to own and carry.[3]

Everyday objects, such as flashlights, baseball bats, newspapers, keyrings with keys, kitchen utensils and other tools, and hair spray aerosol cans in combination with a lighter, can also be used as improvised weapons for self-defense.

Verbal self-defense

Verbal self-defense is defined as using words "to prevent, de-escalate, or end an attempted assault."[4]

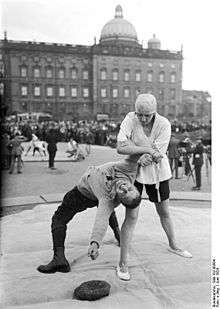

Women's self-defense

According to Victims of Sexual Violence: Statistics on Rainn, about "80 percent of juvenile victims were female and 90 percent of rape victims were adult women".[5] In addition, women from ages 18 to 34 are highly at risk to experience sexual assault. According to historian Wendy Rouse in Her Own Hero: The Origins of Women's Self-Defense Movement, women's self-defense training emerged in the early twentieth century in the United States and the United Kingdom paralleling the women's rights and suffrage movement. These early feminists sought to raise awareness about the sexual harassment and violence that women faced on the street, at work, and in the home. They challenged the notion that men were their "natural protectors" noting that men were often the perpetrators of violence against women. Women discovered a sense of physical and personal empowerment through training in boxing and jiu-jitsu. Interest in women's self-defense paralleled subsequent waves of the women's rights movement especially with the rise of Second-wave feminism in the 1960s and 1970s and Third-wave feminism in the 1990s.[6] Today's Empowerment Self-Defense (ESD) courses focus on teaching verbal and psychological as well as physical self-defense strategies. ESD courses explore the multiple sources of gender-based violence especially including its connections with sexism, racism, and classism. Empowerment Self-Defense instructors focus on holding perpetrators responsible while empowering women with the idea that they have both the right and ability to protect themselves.[7][8][9][10]

Self-defense education

Self-defense techniques and recommended behavior under the threat of violence is systematically taught in self-defense classes. Commercial self-defense education is part of the martial arts industry in the wider sense, and many martial arts instructors also give self-defense classes. While all martial arts training can be argued to have some self-defense applications, self-defense courses are marketed explicitly as being oriented towards effectiveness and optimized towards situations as they occur in the real world. Many systems are taught commercially, many tailored to the needs of specific target audiences (e.g. defense against attempted rape for women, self-defense for children and teens). Notable systems taught commercially include:

- Civilian versions of modern military combatives, such as Krav-Maga, Defendo, Spear, Systema

- Jujutsu and arts derived from it, such as Aikijujutsu, Aikido, Bartitsu, German ju-jutsu, Kodokan Goshin Jutsu.

- Model Mugging

- Traditional unarmed fighting styles like Karate, Taekwondo, Kung fu, Hapkido, Pencak Silat, etc. These styles can also include competing.

- Traditional armed fighting styles like Kali/Eskrima/Arnis. These include competing, as well as armed and unarmed combats.

- Street Fighting oriented, unarmed systems, such as Jeet Kune Do, Kajukenbo, Won Sung Do and Keysi Fighting Method

- Martial sports, such as boxing, kickboxing, Muay Thai, savate, shoot boxing, Sanshou, grappling, judo, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, Sambo, mixed martial arts, and wrestling.

Legal aspects

Application of the law

In any given case, it can be difficult to evaluate whether force was excessive. Allowances for great force may be hard to reconcile with human rights.

The Intermediate People's Court of Foshan, People's Republic of China in a 2009 case ruled the killing of a robber during his escape attempt to be justifiable self-defense because "the robbery was still in progress" at this time.[11]

In the United States between 2008 and 2012, approximately 1 out of every 38 gun-related deaths (which includes murders, suicides, and accidental deaths) was a justifiable killing, according to the Violence Policy Center.[12]

See also

Unarmed self-defense

- Anti-theft system

- Armored car

- Body armor

- Bodyguard

- Cyber self-defense

- Digital self-defense

- Door security

- Gated community

- GPS tracking unit

- Guard dog

- Hand to hand combat

- Intrusion alarm

- Peroneal strike

- Personal alarms

- Physical security

- Safe room

- Secure telephone

- Video surveillance systems

Armed self-defense

- Airgun

- Ballistic knife

- Baton (law enforcement) / Tonfa (martial arts)

- Boot knife

- Brass knuckles

- Club (weapon)

- Crossbow

- CS gas

- Defense wound

- Defensive gun use

- Electroshock weapon

- Gun safety

- Handgun

- Hiatt speedcuffs

- Hollow-point bullet

- Knife / Combat knife

- Laser pointer

- Laser sight

- Mace (spray)

- Millwall brick

- Nunchuku

- Offensive weapon

- Paintball gun

- PAVA spray

- Pepper spray

- Personal defense weapon

- Riot shotgun

- Self-defence in international law

- Slapjack (weapon)

- Slingshot

- Stun grenade

- Switchblade

- Taser

- Throwing knife

- Tranquilizer gun

- Weighted-knuckle glove

Legal and moral aspects

- Battered woman defense

- Castle doctrine

- Concealed carry

- Duty to retreat

- Gun-free zone

- Gun laws in the United States (by state)

- Gun politics

- Gun politics in the United States

- Justifiable homicide

- Non-aggression principle

- Open Carry

- Reasonable force

- Self-defence in international law

- Self-preservation

- Sell your cloak and buy a sword

- Stand-your-ground law

- Use of force

- Turning the other cheek

References

- Dictionary.com's Definition of "Self-Defense". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved on 2012-06-02.

- Kopel, David B.; Gallant, Paul; Eisen, Joanne D. (2008). "The Human Right of Self-Defense" (PDF). BYU Journal of Public Law. BYU Law School. 22: 43–178.

- Branded a criminal - Red Offender spray is rolled out at Canterbury's nightspots (KentOnLine.co.uk, 13 May 2010). Retrieved on 2012-08-05.

- Mattingly, Katy (July 2007). Self-defense: steps to surviva. Human Kinetics. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7360-6689-1. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- "Victims of Sexual Violence: Statistics | RAINN". www.rainn.org. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Rouse, Wendy Her Own Hero: The Origins of the Women's Self-Defense Movement. New York: New York University Press, 2017. https://nyupress.org/9781479828531/her-own-hero/

- Senn, Charlene Y.; Eliasziw, Misha; Barata, Paula C.; Thurston, Wilfreda E.; Newby-Clark, Ian R.; Radtke, H. Lorraine; Hobden, Karen L. (11 June 2015). "Efficacy of a Sexual Assault Resistance Program for University Women". New England Journal of Medicine. 372 (24): 2326–2335. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1411131. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 26061837.

- Hollander, Jocelyn A. (April 2013). "Does Self-Defense Training Prevent Sexual Violence Against Women?". Violence Against Women. 20 (3): 252–269. doi:10.1177/1077801214526046. ISSN 1077-8012. PMID 24626766.

- Thompson, Martha E. (2013–14). "Empowering Self-Defense Training". Violence Against Women. 20 (3): 351–359. doi:10.1177/1077801214526051. ISSN 1077-8012.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- McCaughey, Martha; Cermele, Jill (2013–14). "Guest Editors' Introduction". Violence Against Women. 20 (3): 247–251. doi:10.1177/1077801214526047. ISSN 1077-8012. PMID 24742868.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Are There Limits to Self-Defense? Beijing Review, 28 April 2009.

- Martelle, Scott (19 June 2015). "Gun and self-defense statistics that might surprise you -- and the NRA". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

External links

| Look up self-defense in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Self-defense |