Scribe

A scribe is a person who serves as a professional copyist, especially one who made copies of manuscripts before the invention of automatic printing.[1][2]

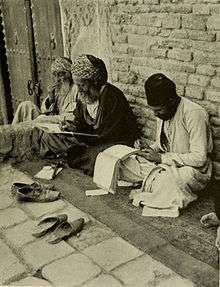

The profession of the scribe, previously widespread across cultures, lost most of its prominence and status with the advent of the printing press. The work of scribes can involve copying manuscripts and other texts as well as secretarial and administrative duties such as the taking of dictation and keeping of business, judicial, and historical records for kings, nobles, temples, and cities. The profession has developed into public servants, journalists, accountants, bookkeepers, typists, and lawyers. In societies with low literacy rates, street-corner letter-writers (and readers) may still be found providing scribe service.[3]

Ancient Egypt

One of the most important professionals in ancient Egypt was a person educated in the arts of writing (both hieroglyphics and hieratic scripts, as well as the demotic script from the second half of the first millennium BCE, which was mainly used as shorthand and for commerce) and arithmetic.[4][5] Sons of scribes were brought up in the same scribal tradition, sent to school, and inherited their fathers' positions upon entering the civil service.[6]

Much of what is known about ancient Egypt is due to the activities of its scribes and the officials. Monumental buildings were erected under their supervision,[7] administrative and economic activities were documented by them, and stories from Egypt's lower classes and foreign lands survive due to scribes putting them in writing.[7]:296

Scribes were considered part of the royal court, were not conscripted into the army, did not have to pay taxes, and were exempt from the heavy manual labor required of the lower classes (corvée labor). The scribal profession worked with painters and artisans who decorated reliefs and other building works with scenes, personages, or hieroglyphic text.

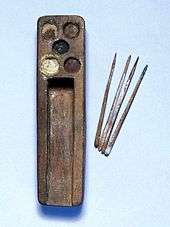

The demotic scribes used rush pens which had stems thinner than that of a reed (2 mm). The end of the rush was cut obliquely and then chewed, so that the fibers became separated. The result was a short, stiff brush which was handled in the same manner as that of a calligrapher.[8]

Thoth was the god credited with the invention of writing by the ancient Egyptians. He was the scribe of the gods who held knowledge of scientific and moral laws.[9]

Egyptian and Mesopotamian functions

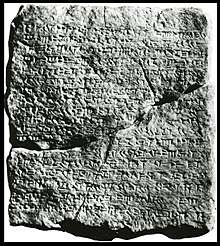

In addition to accountancy and governmental politicking, the scribal professions branched out into literature. The first stories were probably creation stories and religious texts. Other genres evolved, such as wisdom literature, which were collections of the philosophical sayings from wise men. These contain the earliest recordings of societal thought and exploration of ideas in some length and detail.

In Mesopotamia during the middle to late 3rd millennium BCE, the Sumerians originated some of this literature in the form of a series of debates. Among the list of Sumerian disputations is the Debate between bird and fish.[10] Other Sumerian examples include the Debate between Summer and Winter where Winter wins, and disputes between the cattle and grain, the tree and the reed, silver and copper, the pickaxe and the plough, and the millstone and the gul-gul stone.[11]

An Ancient Egyptian version is The Dispute between a man and his Ba, which comes from the Middle Kingdom period.

Judaism

As early as the 11th century BCE, scribes in Ancient Israel, were distinguished professionals who would exercise functions which today could be associated with lawyers, journalists, government ministers, judges, or financiers.[12] Some scribes also copied documents, but this was not necessarily part of their job.[13]

The Jewish scribes used the following rules and procedures while creating copies of the Torah and eventually other books in the Hebrew Bible.[14]

- They could only use clean animal skins, both to write on, and even to bind manuscripts.

- Each column of writing could have no less than 48, and no more than 60, lines.

- The ink must be black, and of a special recipe.

- They must say each word aloud while they were writing.

- They must wipe the pen and wash their entire bodies before writing the most Holy Name of God, YHVH, every time they wrote it.

- There must be a review within thirty days, and if as many as three pages required corrections, the entire manuscript had to be redone.

- The letters, words, and paragraphs had to be counted, and the document became invalid if two letters touched each other. The middle paragraph, word and letter must correspond to those of the original document.

- The documents could be stored only in sacred places (synagogues, etc.).

- As no document containing God's Word could be destroyed, they were stored, or buried, in a genizah (Hebrew: "storage").

Sofer

Sofers (Jewish scribes) are among the few scribes that still do their trade by hand, writing on parchment. Renowned calligraphers, they produce the Hebrew Torah scrolls and other holy texts.

Accuracy

Until 1948, the oldest known manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible dated back to CE 895. In 1947, a shepherd boy discovered some scrolls dated between 100 BCE and CE 100, inside a cave west of the Dead Sea. Over the next decade, more scrolls were found in caves and the discoveries became known collectively as the Dead Sea Scrolls. Every book in the Hebrew Bible was represented except Esther. Numerous copies of each book were discovered, including 25 copies of the book of Deuteronomy.

While there were other items found among the Dead Sea Scrolls not currently in the Hebrew Bible, and many variations and errors occurred when they were copied, the texts on the whole testify to the accuracy of the scribes.[15] The Dead Sea Scrolls are currently the best route of comparison to the accuracy and consistency of translation for the Hebrew Bible because they are the oldest out of any Biblical text currently known.

Corrections by the scribes and editing biblical literature

Priests who took over the leadership of the Jewish community preserved and edited biblical literature. Biblical literature became a tool that legitimated and furthered the priests' political and religious authority.[16]

Corrections by the scribes (Tiqqun soferim) refers to changes that were made in the original wording of the Hebrew Bible wording during the second temple period, perhaps sometime between 450 and 350 BCE. One of the most prominent men at this time was Ezra the scribe. He also hired scribes to work for him, in order to write down and revise the oral tradition.[17] After Ezra and the scribes had completed the writing, Ezra gathered the Jews who had returned from exile, all of whom belonged to Kohanim families. Ezra read them an unfamiliar version of the Torah. This version was different from the Torah of their fathers. Ezra did not write a new bible. Through the genius of his ‘editing’, he presented the religion in a new light.[18][19]

Europe in the Middle Ages

Monastic scribes

In the Middle Ages, every book was made by hand. Specially trained monks, or scribes, had to carefully cut sheets of parchment, make the ink, write the script, bind the pages, and create a cover to protect the script. This was all accomplished in a monastic writing room called a scriptorium which was kept very quiet so scribes could maintain concentration.[20] A large scriptorium may have up to 40 scribes working.[21] Scribes woke to morning bells before dawn and worked until the evening bells, with a lunch break in between. They worked every day except for the Sabbath.[22] The primary purpose of these scribes was to promote the ideas of the Christian Church, so they mostly copied classical and religious works. The scribes were required to copy works in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew whether or not they understood the language.[22] These re-creations were often written in calligraphy and featured rich illustrations, making the process incredibly time-consuming. Scribes had to be familiar with the writing technology as well. They had to make sure that the lines were straight and the letters were the same size in each book that they copied.[23] It typically took a scribe fifteen months to copy a Bible.[22] Such books were written on parchment or vellum made from treated hides of sheep, goats, or calves. These hides were often from the monastery's own animals as monasteries were self-sufficient in raising animals, growing crops, and brewing beer.[21] The overall process was too extensive and costly for books to become widespread during this period.[20] Although scribes were only able to work in daylight, due to the expense of candles and the rather poor lighting they provided, monastic scribes were still able to produce three to four pages of work per day.[22] The average scribe could copy two books per year.[21] They were expected to make at least one mistake per page.[23]

Female Scribes

Women also played a role as scribes in Anglo-Saxon England, as religious women in convents and schools were literate. Excavations at medieval convents have uncovered styli, indicating that writing and copying were done at those locations.[24] Also, female pronouns are used in prayers in manuscripts from the late 8th century, suggesting that the manuscripts were originally written by and for female scribes.[25]

Most of the evidence for female scribes in the early middle ages in Rome is epigraphic. There has been uncovered eleven Latin inscriptions from Rome that identify women as scribes. In these inscriptions we meet with Hapate who was known as a shorthand writer of Greek and lived until the age of 25. Corinna who was known as a storeroom clerk and scribe. Three were identified as literary assistants; Tyche, Herma, and Plaetoriae. There were also four women who have been identified by the title of libraria. Libraria is a term that not only indicates clerk or secretary but more specifically literary copyist. These women were Magia, Pyrrhe, Vergilia Euphrosyne and a freed woman who remains nameless in the inscription.To the inscriptions and literary references we can add one final piece of Roman-period evidence for female scribes: an early-second-century marble relief from Rome that preserves an illustration of a female scribe. The woman is seated on a chair and appears to be writing on some kind of a tablet, she is facing the butcher who is chopping meat at a table.[26]

In the twelfth century within a Benedictine monastery at Wessobrunn, Bavaria there lived a female scribe named Diemut. She lived within the monastery as recluse and professional scribe. Two medieval book lists exist that have named Diemut as having written more than forty books. Fourteen of Diemut’s books are in existence today. Included in these are four volumes of a six volume set of Pope Gregory the Great’s Moralia in Job, two volumes of a three volume Bible, and an illuminated copy of the Gospels. It has been discovered that Diemut was a scribe for as long as five decades. She collaborated with other scribes in the production of other books. Since the Wessobrunn monastery enforced it’s strict claustration it is presumed that these other scribes were also women. Diemut was credited with writing so many volumes that she single handedly stocked the Wessobrunn’s library. Her dedication to book production for the benefit of the Wessobrunn monks and nuns eventually led to her being recognized as a local saint. At the Benedictine monastery within Admont, Austria it was discovered that some of the nuns had written verse and prose in both Latin and German. They delivered their own sermons, took dictation on wax tablets, and copied and illuminated manuscripts. They also taught Latin grammar and biblical interpretation at the school. By the end of the twelfth century they owned so many books that they needed someone to oversee their scriptorium and library. Two female scribes have been identified within the Admont Monastery; Sisters Irmingart and Regilind.[27]

There are several hundred women scribes that have been identified in Germany. These women worked within German women’s convent from the thirteenth to early sixteenth century. Most of these women can only be identified by their names or initials, by their label as “scriptrix”, “soror”, “scrittorix”, “scriba” or by the colophon (scribal identification which appears at the end of a manuscript). Some of the women scribes can be found through convent documents such as obituaries, payment records, book inventories, and narrative biographies of the individual nuns found in convent chronicles and sister books. These women are united by their contributions to the libraries of women’s convents. Many of them remain unknown and unacknowledged but they served the intellectual endeavor of preserving, transmitting and on occasion creating texts. The books they left their legacies within were usually given to the sister of the convent and were dedicated to the abbess, or given or sold to the surrounding community. There are two obituaries that have been found that date back to the sixteenth century, both of the obituaries describe the women who died as a “scriba”. In an obituary found from a monastery in Rulle, describes Christina Von Haltren as having written many other books.[28]

Women’s monasteries were different to men’s in the period from the thirteenth to sixteenth century. They would shift their order depending on their abbess. If a new abbess would be appointed then the order would change their identity. Every time a monastery would shift their order they would need to replace, correct and sometimes rewrite their texts. Many books survived from this period. Approximately 4,000 manuscripts have been discovered from women’s convents from late medieval Germany. Women scribes served as the business women of the convent. They produced a large amount of archival and business materials, they recorded the information of the convent in the form of chronicles and obituaries. They were responsible for producing the rules, statutes and constitution of the order. They also copied a large amount of prayer books and other devotional manuscripts. Many of these scribes were discovered by their colophon.[28]

Town scribe

The scribe was a common job in medieval European towns during the 10th and 11th centuries. Many were employed at scriptoria owned by local schoolmasters or lords. These scribes worked under deadlines to complete commissioned works such as historic chronicles or poetry. Due to parchment being costly, scribes often created a draft of their work first on a wax or chalk tablet.[29]

Notable scribes

- Ahmes

- Amat-Mamu

- Baruch

- Dubhaltach MacFhirbhisigh

- Demetrius Erasmius

- Máel Muire mac Céilechair

- Sidney Rigdon

- Sin-liqe-unninni

See also

References

- Harper, Douglas (2010). "Scribe". Dictionary.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Dictionary.com, LLC. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

-

- "Women of letters doing write for the illiterate". smh.com.au. Reuters. 12 June 2003. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Rice, Michael (1999). Who's Who in Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge. p. lvi. ISBN 978-0415154482.

- Damerow, Peter (1996). Abstraction and Representation: Essays on the Cultural Evolution of Thinking. Dordrecht: Kluwer. pp. 188–. ISBN 978-0792338161.

- Carr, David M. (2005). Writing on the Tablet of the Heart: Origins of Scripture and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0195172973.

- Kemp, Barry J. (2006). Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. p. 180. ISBN 978-0415235495.

- Clarysse, Willy (1993). "Egyptian Scribes Writing Greek". Chronique d'Égypte. 68 (135–136): 186–201. doi:10.1484/J.CDE.2.308932.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (1969). The Gods of the Egyptians. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486220550.

- "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". Etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk. 2006-12-19. Retrieved 2017-03-09.

- "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". Etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk. 2006-12-19. Retrieved 2017-03-09.

- "Hebrew language, alphabet and pronunciation". Omniglot.com. Retrieved 2017-03-09.

- Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D. (1993). The Oxford Companion to the Bible (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195046458.

- Manning, Scott (17 March 2007). "Process of copying the Old Testament by Jewish Scribes". Historian on the Warpath. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Johnson, Paul (1993). A History of the Jews (2nd ed.). London: Phoenix. p. 91. ISBN 978-1857990966.

- Schniedewind, William M. (18 November 2008). "Origins of the Written Bible". Nova. PBS Online. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Drazin, Israel (26 August 2015). "Ezra changed the Torah text". Jewish Books. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Okouneff, M. (23 January 2016). Greenburg, John (ed.). The Wrong Scribe: The Scribe Who Revised the King David Story. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 146. ISBN 9781523640430.

- Gilad, Elon (22 October 2014). "Who Wrote the Torah?". Haaretz. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Pavlik, John; McIntosh, Shawn (2017). Converging Media: A New Introduction to Mass Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 9780190271510.

- Murray, Stuart A.P. (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing. pp. 33–34. ISBN 9781602397064.

- Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: A Living History. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. pp. 36–38, 41. ISBN 9781606060834.

- Martyn., Lyons (2011). Books : a living history. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 9781606060834. OCLC 707023033.

- Lady Science (16 February 2018). "Women Scribes: The Technologists of the Middle Ages". The New Inquiry.

- "Female Scribes in Early Manuscripts". Medieval manuscripts blog.

- Haines-Eitzen, Kim (Winter 1998). "Girls Trained in Beautiful Writing: Female Scribes in Roman Antiquity and Early Christianity". Journal of Early Christian Studies. 6 (4): 629–646. doi:10.1353/earl.1998.0071.

- Hall, Thomas N. (Summer 2006). "Women as Scribes: Book Production and Monastic Reform in Twelfth Century Bavaria". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 37: 160–162 – via Gale.

- Cyrus, Cynthia (2009). The Scribe for Women's Convents in Late Medieval Germany. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802093691.

- Murray, Stuart A.P. (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 9781602397064.

Further reading

- Avrin, Leila (2010). Scribes, Scripts and Books. ALA Publishing. ISBN 978-0838910382.

- Martin, Henri-Jean (1995). The History and Power of Writing. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-50836-6.

- Richardson, Ernest Gushing (1911). Some Old Egyptian Librarians. Charles Sribners.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Scribe |

| Look up scribe in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scribes. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scribes of Ancient Egypt. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Catholic Encyclopedia. newadvent.org.