Scottish diaspora

The Scottish diaspora consists of Scottish people who emigrated from Scotland and their descendants. The diaspora is concentrated in countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia, England, New Zealand, Ireland and to a lesser extent Argentina, Chile and Brazil.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 28–40 million worldwideA[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 6,006,955 & 5,393,554[3][4] | |

| 4,719,850[5] | |

| 1,792,600[6] | |

| 795,000 | |

| 100,000 | |

| 80,000 | |

| 45,000 | |

| 15,000 | |

| 12,792[7] | |

| 11,160 | |

| 2,403[8] | |

| 1,459[9][10][11] | |

| Languages | |

| Scottish English • Scottish Gaelic • Scots | |

| Religion | |

| Presbyterianism • Roman Catholicism • Episcopalianism • deists • atheists. | |

A These figures are estimates based on official census data of populations and official surveys of identity.[12][13][14][15] B Scottish Americans and Scotch-Irish Americans. C Scottish Canadians. D Scottish born people in England only E Ulster-Scots F missing G Number of people born in Scotland. | |

Americas

Argentina

A Scottish Argentine population has existed at least since 1825.[16] There are an estimated 100,000 Argentines of Scottish ancestry, the most of any country outside the English-speaking world.[17] Scottish Argentines have been incorrectly referred to as English.[18]

Brazil

Canada

Scottish people have a long history in Canada, dating back several centuries. Many towns, rivers and mountains have been named in honour of Scottish explorers and traders such as Mackenzie Bay and Calgary is named after a Scottish beach. Most notably, the Atlantic province of Nova Scotia is Latin for New Scotland. Once Scots formed the vanguard of the movement of Europeans across the continent. In more modern times, emigrants from Scotland have played a leading role in the social, political and economic history of Canada, being prominent in banking, labour unions, and politics.[19]

The first documented Scottish settlement in the Americas was of Nova Scotia (New Scotland) in 1629. On 29 September 1621, the charter for the foundation of a colony was granted by James VI of Scotland to Sir William Alexander.[20] Between 1622 and 1628, Sir William launched four attempts to send colonists to Nova Scotia; all failed for various reasons. A successful occupation of Nova Scotia was finally achieved in 1629. The colony's charter, in law, made Nova Scotia (defined as all land between Newfoundland and New England) a part of mainland Scotland. The Scots have influenced the cultural mix of Nova Scotia for centuries and constitute the largest ethnic group in the province, at 29.3% of its population. Many Scottish immigrants were monoglot Scottish Gaelic speakers from the Gàidhealtachd (Scottish Highlands). Canadian Gaelic was spoken as the first language in much of "Anglophone" Canada, such as Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Glengarry County in Ontario. Gaelic was the third most commonly spoken language in Canada.[21]

As the third-largest ethnic group in Canada and amongst the first Europeans to settle in the country, Scottish people have made a large impact on Canadian culture since colonial times. According to the 2011 Census of Canada, the number of Canadians claiming full or partial Scottish descent is 4,714,970,[22] or 15.10% of the nation's total population.

Chile

A large proportion of Scottish Chileans are sheep farmers in the Magallanes region of the far south of the country, and the city of Punta Arenas has a large Scottish foundation dating back to the 18th century. A famous Scot, Thomas, Lord Cochrane (later 10th Earl of Dundonald) formed the Chilean Navy to help liberate Chile from Spain in the independence period. Chile developed a strong diplomatic relationship with Great Britain and invited more British settlers to the country in the 19th century.

The Chilean government land deals invited settlement from Scotland and Wales in its southern provinces in the 1840s and 1850s. The number of Scottish Chileans is still higher in Patagonia and Magallanes regions. The Mackay School, in Viña del Mar is an example of a school set up by Scottish Chileans. The Scottish and other British Chileans are primarily found in higher education as well in economic management and the country's cultural life.

United States

| Scottish ancestry in the United States, 1700–2013 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Ethnic group | Population | % of pop. | R |

| 1700 est | Scottish | 7,526 | 3.0% | [23][24] |

| 1755 est | Scottish & Scots-Irish | 4.0% & 7.0% (11.0%) | [23] | |

| 1775 est | Scottish & Scots-Irish | 6.6% & 7.8% (14.4%) | [25] | |

| 1790 est | Scottish & Scots-Irish | 6.6% & 4.8% (11.4%) | [26][27] | |

| 1980 | Scottish & Scots-Irish | 10,048,816 & 16,418 | 4.44% & 0.007% (4.447%) | [28] |

| 1990 | Scottish & Scots-Irish | 5,393,581 & 5,617,773 | 2.2% & 2.3% (4.5%) | [29] |

| 2000 | Scottish & Scots-Irish | 4,890,581 & 4,319,232 | 1.7% & 1.5% (3.2%) | [30] |

| 2010 (ACS) | Scottish & Scots-Irish | 5,460,679 & 3,257,161 | 1.9% & 3.1% | [31] |

| 2013 (ACS) | Scottish & Scots-Irish | 5,310,285 & 2,976,878 | ?% | [31] |

In the 2013 American Community Survey 5,310,285 identified as Scottish & 2,976,878 Scots-Irish descent.[32] Large scale emigration from Scotland to America began in the 1700s after the Battle of Culloden where the Clan structures were broken up. Anti-Catholic persecution[33][34] and the Highland Clearances also obliged many Scottish Gaels to emigrate. The Scots went in search of a better life and settled in the thirteen colonies, mainly around South Carolina and Virginia.

The number of Americans of Scottish descent today is estimated to be 20 to 25 million[35][36][37][38] (up to 8.3% of the total US population), and Scotch-Irish, 27 to 30 million[39][40] (up to 10% of the total US population), the subgroups overlapping and not always distinguishable because of their shared ancestral surnames.

The majority of Scotch-Irish originally came from Lowland Scotland and the Scottish Borders before migrating to the province of Ulster in Ireland (see Plantation of Ulster) and thence, beginning about five generations later, to North America in large numbers during the eighteenth century.

The table shows the ethnic Scottish population in the United States from 1700 to 2013. In 1700 the total population of the American colonies was 250,888 of which 223,071 (89%) were white and 3.0% were ethnically Scottish.[23][24] In the 2000 census, 4.8 million Americans self-reported Scottish ancestry, 1.7% of the total US population. Another 4.3 million self-reported Scotch-Irish ancestry, for a total of 9.2 million Americans self-reporting some kind of Scottish descent.

Self-reported numbers are regarded by demographers as massive under-counts, because Scottish ancestry is known to be disproportionately under-reported among the majority of mixed ancestry,[41] and because areas where people reported "American" ancestry were the places where, historically, Scottish and Scotch-Irish Protestants settled in America (that is: along the North American coast, Appalachia, and the Southeastern United States).

Scottish Americans descended from nineteenth-century Scottish immigrants tend to be concentrated in the West, while others in New England are the descendants of immigrants from the Maritime Provinces of Canada, especially in the 1920s.

Americans of Scottish descent outnumber the population of Scotland, where 4,459,071 or 88.09% of people identified as ethnic Scottish in the 2001 Census.[42][43] There are many clan societies and other heritage organizations, such as An Comunn Gàidhealach America and Slighe nan Gàidheal.

Asia-Pacific

Australia

| Scottish ancestry in Australia, 1986–2011 (Census) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Population | Percent of pop. | Ref | |

| 1986 | 740,522 | 4.7% | [44] | |

| 2001 | 540,046 | 2.9% | [44] | |

| 2006 | 1,501,200 | 7.6% | [45][46] | |

| 2011 | 1,792,622 | 8.3% | [46][47] | |

A steady rate of Scottish immigration continued into the 20th century, with substantial numbers of Scots continued to arrive after 1945.[48] From 1900 until the 1950s, Scots favoured New South Wales, as well as Western Australia and Southern Australia. A strong cultural Scottish presence is evident in the Highland games, dance, Tartan day celebrations, Clan and Gaelic speaking societies found throughout modern Australia.

According to the 2011 Australian census 130,204 Australian residents were born in Scotland,[49] while 1,792,600 claimed Scottish ancestry, either alone or in combination with another ancestry.[6] This is the fourth most commonly nominated ancestry and represents over 8.9% of the total population of Australia.

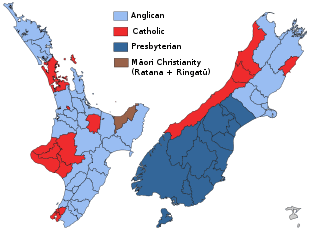

New Zealand

Scottish migration to New Zealand dates back to the earliest period of European colonisation, with a large proportion of Pākehā New Zealanders being of Scottish descent.[50] However, identification as "British" or "European" New Zealanders can sometimes obscure their origin. Many Scottish New Zealanders also have Māori or other non-European ancestry.

The majority of Scottish immigrants settled in the South Island. All over New Zealand, the Scots developed different means to bridge the old homeland and the new. Many Caledonian societies were formed, well over 100 by the early twentieth century, who helped maintain Scottish culture and traditions. From the 1860s, these societies organised annual Caledonian Games throughout New Zealand. The Games were sports meets that brought together Scottish settlers and the wider New Zealand public. In so doing, the Games gave Scots a path to cultural integration as Scottish New Zealanders.[51]

The Lay Association of the Free Church of Scotland founded Dunedin at the head of Otago Harbour in 1848 as the principal town of its Scottish settlement. The name comes from Dùn Èideann, the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, the Scottish capital.[52] Charles Kettle the city's surveyor, instructed to emulate the characteristics of Edinburgh, produced a striking, 'Romantic' design.[53] The result was both grand and quirky streets as the builders struggled and sometimes failed to construct his bold vision across the challenging landscape. Captain William Cargill, a veteran of the war against Napoleon, was the secular leader. The Reverend Thomas Burns, a nephew of the poet Robert Burns, was the spiritual guide.

Europe

Ireland

The Ulster-Scots (Ulster-Scots: Ulstèr-Scotch), commonly known as Scots-Irish outside of Ireland, are an ethnic group in Ireland, found mostly in the Ulster region and to a lesser extent in the rest of Ireland. Their ancestors were mostly Protestant Lowland Scottish migrants, the largest numbers coming from Galloway, Lanarkshire, Stirlingshire, and Ayrshire, although some came from further north in the Scottish Lowlands (Perthshire and the Northeast) and also to a lesser extent from the Highlands.

These Scots migrated to Ireland in large numbers both as a result of the government-sanctioned Plantation of Ulster and the previous and contemporary settlement of Scots in Antrim and Down by James Hamilton, Hugh Montgomery, and Lord Randal MacDonnell; the former a planned process of colonisation beginning in 1610 which took place under the auspices of King James I on land confiscated from members of the Gaelic nobility of Ireland who fled Ulster and the latter a private scheme beginning in 1606, but also authorised by King James.

Ulster-Scots emigrated onwards from Ireland in significant numbers to what is now the United States and to all corners of the then-worldwide British Empire; Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, the West Indies, British India, and to a lesser extent Argentina and Chile. Scotch-Irish (or Scots-Irish) is a traditional term for Ulster-Scots in North America.

Poland

From as far back as the mid-16th century, historical records document the presence of Scots trading, serving as mercenary soldiers, and settling in Poland.[54] The vast majority were traders, from wealthy merchants to the thousands of pedlars who ensured that the term szot became synonymous in the Polish language with "tinker".[55] A "Scotch Pedlar's Pack in Poland" became a proverbial expression. It usually consisted of cloths, woollen goods and linen kerchiefs (head coverings). Itinerants also sold tin utensils and ironware such as scissors and knives. By 1562 the community was sizeable enough that the Scots, along with the Italians, were recognized by the Sejm as traders whose activities were harming Polish cities; in 1566 they were banned from roaming and peddling their wares.[56]

However, from the 1570s onward, it was recognized that such bans were ineffectual. A heavy tax was placed upon them instead. Thomas Chamberlayne, an English eyewitness, described them disapprovingly in a 1610 letter to Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury, stating that "[t]hese Scotts for the most parte are height landers [i.e. highlanders] men of noe credit, a Company of pedeling knaves..."[57] Linked to some degree of persecution and their role in the Danzig uprising, protection (and by extension, a form of control) was offered by King Stephen Báthory in the Royal Grant of 1576, assigning Scottish immigrants to a district in Kraków. By the first half of the 17th century, the affairs of the Scottish community were regulated by twelve Brotherhoods with seats across various Polish cities; this included a tribunal that met to adjudicate disputes in the Royal Prussian city of Toruń.[58]

Scottish mercenary soldiers first served in large numbers in the late 1570s. Many were former traders. According to Spytko Wawrzyniec Jordan, one of King Stephen Báthory's captains, they were former pedlars who, "having abandoned or sold their booths...buckle on their sword and shoulder their musket; they are infantry of unusual quality, although they look shabby to us...2000 Scots are better than 6000 of our own infantry."[59] It is possible that the shift from peddling to military occupations was connected to the implementation of heavy taxation on pedlars in the 1570s. Scottish mercenary soldiers were recruited specifically by King Stephen Báthory following his experience with them in forces raised by Danzig against him in 1577.[60] Báthory commented favourably upon the Scots and expressed a wish for them to be recruited in campaigns that he was planning against Muscovy. A steady stream of Scots soldiers served the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from this point forward.

Records from 1592 mention Scots settlers granted citizenship of Kraków, and give their employment as trader or merchant. Fees for citizenship ranged from 12 Polish florins to a musket and gunpowder, or an undertaking to marry within a year and a day of acquiring a holding.

By the 17th century, an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 Scots lived in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[61] Many came from Dundee and Aberdeen. Scots could be found in Polish towns on the banks of the Vistula as far south as Kraków. Settlers from Aberdeenshire were mainly Episcopalians or Catholics, but there were also large numbers of Calvinists. As well as Scottish traders, there were also many Scottish soldiers in Poland. In 1656, a number of Scottish highlanders travelled to Poland, serving under the King of Sweden in his war against it.

The Scots integrated well and many acquired great wealth. They contributed to many charitable institutions in the host country, but did not forget their homeland; for example, in 1701 when collections were made for the restoration fund of the Marischal College, Aberdeen, Scottish settlers in Poland gave generously.

Many royal grants and privileges were granted to Scottish merchants until the 18th century, at which time the settlers began to merge more and more into the native population. "Bonnie Prince Charlie" was half Polish, since he was the son of James Stuart, the "Old Pretender", and Clementina Sobieska, granddaughter of Jan Sobieski, King of Poland.[62][63][64] In 1691, the City of Warsaw elected the Scottish immigrant Aleksander Czamer (Alexander Chalmers) as its mayor.[65]

See also

- English-speaking world

- European diaspora

- Celtic diaspora (disambiguation)

References

- "The Scottish Diaspora and Diaspora Strategy: Insights and Lessons from Ireland". Scottish Government. May 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- "Statistical Bulletins - Scotland Census 2011". Scotlandscensus.gov.uk.

- American Community Survey 2008 Archived 2011-10-28 at the Wayback Machine by the US Census Bureau estimates 5,827,046 people claiming Scottish ancestry and 3,538,444 people claiming Scotch-Irish ancestry.

- "Who are the Scots-Irish?". Parade.com. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- The 2006 Canadian Census gives a total of 4,719,850 respondents stating their ethnic origin as Scottish. Many respondents may have misunderstood the question and the numerous responses for "Canadian" does not give an accurate figure for numerous groups, particularly those of British Isles origins.

- "ABS Ancestry". Abs.gov.au. 2012.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2015-09-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Scotland analysis: Borders and citizenship" (PDF). Gov.uk. p. 70. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "Scotland's Diaspora and Overseas-Born Population" (PDF). Gov.scot. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Scottish Government, St Andrew's House (5 October 2009). "Scotland's Diaspora and Overseas-Born Population". Gov.scot. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "Friends Of Scotland". Friendsofscotland.gov.uk. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- The Ancestral Scotland website states the following: "Scotland is a land of 5.1 million people. A proud people, passionate about their country and her rich, noble heritage. For every single Scot in their native land, there are thought to be at least five more overseas who can claim Scottish ancestry; that's many millions spread throughout the globe."] Ancestralscotland.com

- "History, Tradition and roots, ancestry". Scotland.org. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-12-21. Retrieved 2007-10-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Clan Macrae news". Clan-macrae.org.uk. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Gilchrist, Jim (14 December 2008). "Stories of Homecoming - We're on the march with Argentina's Scots". The Scotsman. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- Pelayes, Hector Darvo. "Footbol AFA". Members.tripod.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-04-16. Retrieved 2017-09-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Fry, Michael (2001). The Scottish Empire. Tuckwell Press. p. 21. ISBN 1-84158-259-X.

- Jonathan Dembling. “Gaelic in Canada: new evidence from an old census.” In Cànan & Cultar/Language & Culture: Rannsachadh na Gàidhlig 3, edited by Wilson McLeod, James Fraser and Anja Gunderloch, 203-14. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press, 2006.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics. "Statistics Canada: Ethnocultural Portrait of Canada Highlight Tables, 2006 Census". 12.statcan.ca.

- Boyer, Paul S.; Clark, Clifford E.; Halttunen, Karen; Kett, Joseph F.; Salisbury, Neal (1 January 2010). "The Enduring Vision: A History of the American People". Cengage Learning – via Google Books.

- Purvis, Thomas L. (14 May 2014). "Colonial America To 1763". Infobase Publishing. Retrieved 11 January 2018 – via Google Books.

- Harr, J. Scott; Hess, Kären M.; Orthmann, Christine Hess; Kingsbury, Jonathon (1 January 2014). "Constitutional Law and the Criminal Justice System". Cengage Learning – via Google Books.

- Parrillo, Vincent N. (11 January 2018). "Diversity in America". Pine Forge Press. Retrieved 11 January 2018 – via Google Books.

- Perlmutter, Philip (11 January 1996). "The Dynamics of American Ethnic, Religious, and Racial Group Life: An Interdisciplinary Overview". Greenwood Publishing Group. Retrieved 11 January 2018 – via Google Books.

- "Rank of States for Selected Ancestry Groups with 100,00 or more persons: 1980" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- "1990 Census of Population Detailed Ancestry Groups for States" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 18 September 1992. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- "Ancestry: 2000". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- "Total ancestry categories tallied for people with one or more ancestry categories reported 2010 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- "Total ancestry categories tallied for people with one or more ancestry categories reported 2013 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- MacKay, Donald (1996). Scotland farewell: The people of the Hector (3, illustrated ed.). Dundurn Press Ltd. ISBN 1-896219-12-8. p. vii.

- Campey, Lucille H (2007). After the Hector: The Scottish Pioneers of Nova Scotia and Cape Breton 1773–1852 (2nd ed.). Toronto: National Heritage Books. ISBN 978-1-55002-770-9. pp. 60–61.

- James McCarthy and Euan Hague, 'Race, Nation, and Nature: The Cultural Politics of "Celtic" Identification in the American West', Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Volume 94 Issue 2 (5 Nov 2004), p. 392, citing J. Hewitson, Tam Blake and Co.: The Story of the Scots in America (Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 1993).

- Tartan Day 2007, Scotlandnow, Issue 7 (March 2007). Accessed 7 September 2008.

- "Scottish Parliament: Official Report, 11 September 2002, Col. 13525". Scottish.parliament.uk. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- "Scottish Parliament: European and External Relations Committee Agenda, 20th Meeting 2004 (Session 2), 30 November 2004, EU/S2/04/20/1" (PDF). Scottish.parliament.uk. 2011-08-14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- James Webb, Born Fighting: How the Scots-Irish Shaped America (New York: Broadway Books, 2004), front flap: 'More than 27 million Americans today can trace their lineage to the Scots, whose bloodline was stained by centuries of continuous warfare along the border between England and Scotland, and later in the bitter settlements of England's Ulster Plantation in Northern Ireland.' ISBN 0-7679-1688-3

- James Webb, Secret GOP Weapon: The Scots Irish Vote, Wall Street Journal (23 October 2004). Accessed 7 September 2008.

- Mary C. Walters, Ethnic Options: Choosing Identities in America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), pp. 31-6.

- "QT-P13. Ancestry: 2000". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- "Table 1.1: Scottish population by ethnic group - All People". Scotland.gov.uk. 2006-04-04. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- The Transformation of Australia's Population: 1970-2030 edited by Siew-An Khoo, Peter F. McDonald, Siew-Ean Khoo.(Page 164).

- The People of Australia - Statistics from the 2006 Census (Page 50) Dss.gov.au

- "The people of Australia.The People of Australia - Statistics from the 2011 Census (Page:55)" (PDF). Omi.wa.gov.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of. "2011 Census data shows more than 300 ancestries". Abs.gov.au. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- M. Prentis (2008). The Scots in Australia. University of New South Wales Press. ISBN 9781921410215.

- "20680-Country of Birth of Person (full classification list) by Sex — Australia" (Microsoft Excel download). 2006 Census. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- "Loading..." Naturemagics.com. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Tanja Bueltmann, "'No Colonists are more Imbued with their National Sympathies than Scotchmen,'" New Zealand Journal of History (2009) 43#2 pp 169–181 online

- McLintock, A H (1949), The History of Otago; the origins and growth of a Wakefield class settlement, Dunedin, NZ: Otago Centennial Historical Publications, OCLC 154645934

- Hocken, Thomas Moreland (1898), Contributions to the Early History of New Zealand (Settlement of Otago), London, UK: Sampson Low, Marston and Company, OCLC 3804372

- "Scotland and Poland - a 500 year relationship". The Scotsman. 24 March 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- Murdoch, Steve (2001). Scotland and the Thirty Years' War: 1618-1648. BRILL.

- Steuart, A. F. (1915). Papers Relating to the Histories of Scots in Poland 1576-1793. Edinburgh.

- "Thomas Chamberlayne to Robert Cecil (Elbląg, 29 Novembris 1610)"". EFE. 4 (68): 81–82.

- Murdoch, Steve (2001). Scotland and the Thirty Years' War: 1618-1648. BRILL.

- Biegánksa, Anna (1984). "Żołnierze szkoccy w dawnej Rzeczpospolitej". Rzeczypospolitej Studia i Materiały do Historii Wojskowości. 27.

- Murdoch, Steve (2001). Scotland and the Thirty Years' War: 1618-1648. BRILL.

- Eric Richards (2004). "Britannia's children: emigration from England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland". Continuum International Publishing Group. p.53. ISBN 1-85285-441-3

- Polish Roots – Rosemary A. Chorzempa – Google Books. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- "Scotland and Poland". Scotland.org. Archived from the original on 2009-03-03. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- "Legacies – Immigration and Emigration – Scotland – North-East Scotland – Aberdeen's Baltic Adventure – Article Page 1". BBC. 5 October 2003. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- "Warsaw | Warsaw's Scottish Mayor Remembered". Warsaw-life.com. Retrieved 19 March 2009.