Science and technology in Armenia

Science and technology in Armenia describes trends and developments in science, technology and innovation policy and governance in Armenia.

Background

Building an efficient research system is a strategic objective for the Armenian authorities.[1] Armenia has a number of assets, including a strong science base, a large Armenian diaspora and traditional national values that emphasize education and skills. Nonetheless, there are still a number of hurdles to overcome in building the national innovation system. The biggest among these are the poor linkages between universities, research institutions and the business sector. This is partly a legacy of the country's Soviet past, when the policy focus was on developing linkages across the Soviet economy rather than within Armenia. Research institutes and industry were part of value chains within a large market that disintegrated with the Soviet Union. Two decades on, domestic businesses have yet to become effective sources of demand for innovation.[2]

Armenia experienced recession in 2009 during the global financial crisis, before returning to modest economic growth. Over the period 2008-2013, Armenia's economy grew by 1.7% per year, on average.[2]

International cooperation

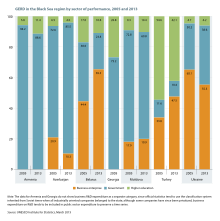

Armenia is a member of the Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC), along with Albania, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Georgia, Greece, Moldova, Romania, the Russian Federation, Serbia, Turkey and Ukraine. This organisation was founded in 1992, shortly after the disintegration of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, in order to develop prosperity and security within the region. One of the BSEC's strategic goals is to deepen cooperation with the European Union. Armenia does not have an association agreement with the European Union (unlike Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine) but is nevertheless eligible to apply for research funding within the European Union's seven-year framework programmes. The European Union has sought to enhance the involvement of countries from the region in these programmes. In co-operation with the BSEC, the European Union’s Networking on Science and Technology in the Black Sea Region project (2009–2012) has been instrumental in funding a number of cross-border co-operative projects, notably in clean and environmentally sound technologies.[2] BSEC's Third Action Plan on Science and Technology 2014–2018 acknowledges that considerable effort has been devoted to setting up a Black Sea Research Programme involving both BSEC and European Union members but also that, ‘in a period of scarce public funding, the research projects the Project Development Fund could support will decrease and, as a result, its impact will be limited’.[3]

Armenia has been a member of the Eurasian Economic Union since October 2014. This body was founded in May 2014 by Belarus, Kazakhstan and the Russian Federation. As co-operation among the member states in science and technology is already considerable and well-codified in legal texts, the Eurasian Economic Union is expected to have a limited additional impact on co-operation among public laboratories or academia but it may encourage research links among businesses and scientific mobility, since it includes provision for the free circulation of labour and unified patent regulations.[2]

Armenia hosts a branch of the International Science and Technology Center (ISTC). ISTC branches are also hosted by other parties to the agreement: Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. ISTIC was established in 1992 by the European Union, Japan, the Russian Federation and the USA to engage weapons scientists in civilian research projects and to foster technology transfer. The headquarters of ISTC were moved to Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan in June 2014, three years after the Russian Federation announced its withdrawal from the centre.

Armenia is also a member of the World Trade Organization.

Science governance

In Armenia, regulations governing ‘public good’ research have tended to be a step ahead of those related to the commercialization of research results. The first legislative act in relation to science and technology was the Law on Scientific and Technological Activity (2000). It defined key concepts related to the conduct of research and related organizations.[2]

State Committee of Science

In 2007, the government made a key policy decision by adopting a resolution establishing the State Committee of Science (SCS). While being a committee within the Ministry of Education and Science, the SCS was empowered with wide-ranging responsibilities as the leading public agency for the governance of science, including the drafting of legislation, rules and regulations on the organization and funding of science. Shortly after the creation of the SCS, competitive project financing was introduced to complement basic funding of public research institutions; this funding has dropped over the years in relative terms. SCS is also the lead agency for the development and implementation of research programmes in Armenia.[4]

Key policy documents

The State Committee of Science led the preparation of three key documents which were subsequently adopted by the government in 2010: the Strategy for the Development of Science 2011–2020, Science and Technology Development Priorities for 2010–2014 and the Strategic Action Plan for the Development of Science for 2011–2015. The Strategy for the Development of Science 2011–2020 envisages a competitive knowledge-based economy drawing on basic and applied research. The Action Plan seeks to translate this vision into operational programmes and instruments supporting research in the country. The Strategy for the Development of Science 2011–2020 envisions that ‘by 2020, Armenia is a country with a knowledge-based economy and is competitive within the European Research Area with its level of basic and applied research.’ The following targets have been formulated:[2]

- Creation of a system capable of sustaining the development of science and technology;

- Development of scientific potential, modernization of scientific infrastructure;

- Promotion of basic and applied research;

- Creation of a synergistic system of education, science and innovation; and

- Becoming a prime location for scientific specialization in the European Research Area.

Based on this strategy, the Action Plan was approved by the government in June 2011. It defined the following targets:[2]

- Improve the S&T management system and create the requisite conditions for sustainable development;

- Involve more young, talented people in education and research, while upgrading research infrastructure;

- Create the requisite conditions for the development of an integrated national innovation system; and

- Enhance international co-operation in research and development.

Although the Strategy clearly pursues a ‘science push’ approach, with public research institutes as the key policy target, it nevertheless mentions the goals of generating innovation and establishing an innovation system. However, the business sector, which is the main driver of innovation, is not mentioned. Inbetween the Strategy and the Action Plan, the government issued a resolution in May 2010 on Science and Technology Development Priorities for 2010–2014. These priorities were:[2]

- Armenian studies, humanities and social sciences;

- Life sciences;

- Renewable energy, new energy sources;

- Advanced technologies, information technologies;

- Space, Earth sciences, sustainable use of natural resources; and

- Basic research promoting essential applied research.

The Law on the National Academy of Sciences (May 2011) is also expected to play a key role in shaping the Armenian innovation system. It allows the academy to carry out wider business activities concerning the commercialization of research results and the creation of spin-offs; it also makes provision for restructuring the National Academy of Sciences by combining institutes involved in closely related research areas into a single body. Three of these new centres are particularly relevant: the Centre for Biotechnology, the Centre for Zoology and Hydro-ecology and the Centre for Organic and Pharmaceutical Chemistry.[2]

In addition to horizontal innovation and science policies, the government strategy focuses support schemes on selected sectors of industrial policy. In this context, the State Committee of Science invites private sector participation on a co-financing basis in research projects targeting applied results. More than 20 projects have been funded in so-called targeted branches: pharmaceuticals, medicine and biotechnology, agricultural mechanization and machine building, electronics, engineering, chemistry and, particularly, the sphere of information technology.[2]

Promotion of science-industry ties

Over the past decade, the government has made an effort to encourage science–industry linkages. The Armenian information technology sector has been particularly active: a number of public–private partnerships have been established between companies and universities, in order to give students marketable skills and generate innovative ideas at the interface of science and business. Examples are Synopsys Inc. and the Enterprise Incubator Foundation.[2]

Synopsys Inc.

.svg.png)

Synopsys Inc. celebrated ten years in Armenia in October 2014. This multinational specializes in the provision of software and related services to accelerate innovation in chips and electronic systems. In 2015, it employed 650 people in Armenia. In 2004, Synopsys Inc. acquired LEDA Systems, which had established an Interdepartmental Chair on Microelectronic Circuits and Systems with the State Engineering University of Armenia. The Chair, now part of the global Synopsys University Programme, supplies Armenia with more than 60 microchip and electronic design automation specialists each year. Synopsys has since expanded this initiative by opening interdepartmental chairs at Yerevan State University, the Russian–Armenian (Slavonic) University and the European Regional Academy.

Enterprise Incubator Foundation

The Enterprise Incubator Foundation (EIF) was founded jointly in 2002 by the government and the World Bank and has since become the driving force of Armenia’s information technology (IT) sector. It acts as a ‘one-stop agency’ for this sector, dealing with legal and business aspects, educational reform, investment promotion and start-up funding, services and consultancy for IT companies, talent identification and workforce development. It has implemented various projects in Armenia with international companies such as Microsoft, Cisco Systems, Sun Microsystems, Hewlett Packard and Intel. One such project is the Microsoft Innovation Center, which offers training, resources and infrastructure, as well as access to a global expert community. In parallel, the Science and Technology Entrepreneurship Programme helps technical specialists bring innovative products to market and create new ventures, as well as encouraging partnerships with established companies. Each year, EIF organizes the Business Partnership Grant Competition and Venture Conference. In 2014, five winning teams received grants for their projects of either US$7,500 or US$15,000. EIF also runs technology entrepreneurship workshops, which offer awards for promising business ideas.

Armenia: land of surprising engineering

A public website www.whyarmenia.am was created to tell more about Armenia as Information Technology outsourcing hub. The page is dedicated to present how such a little country has introduced to the world so many groundbreaking innovations for over 6000 years. Yet, more often than not, the world has had no clue that Armenians were behind such radical breakthroughs. Disruptive technologies like the MRI, the ATM, the color TV, the automatic transmission, and much more have been invented by Armenians. Armenia has just launched what it aims to be the world's leading high-school level robotics curriculum. While it is still only in pilot phase in 60 schools, by 2020 it will be in every school in the country and over 50,000 budding engineers will be trained robotics developers. Why Armenia page introduces many interesting aspects of the country and the nation that are known for their creativity and innovative minds. It also introduces to Armenian based leading Software Development global outsourcing Companies like Priotix software development, SFL, Workfront etc.

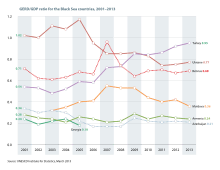

Financial investment in research

Gross domestic expenditure on research and development is low in Armenia, averaging 0.25% of GDP over 2010–2013, with little annual variation observed in recent years. This is only around one-third of the ratios observed in Belarus and Ukraine. However, the statistical record of research expenditure is incomplete in Armenia, as expenditure in the privately owned business enterprises is not surveyed. With this proviso, one can affirm that the share of research funding from the state budget has increased since the 2008–2009 global financial crisis and accounted for around two-thirds (66.3%) of domestic spending on research in 2013.[2]

Human resources

Research

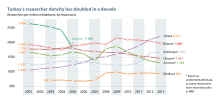

The number of researchers (in head counts) in the public sector has dropped by 27% since 2008, to 3,870 (2013), a casualty of the global financial crisis of 2008–2009. Female researchers accounted for 48.1% of the total in 2013. Like other former Soviet states, Armenia has long since achieved gender parity in science and engineering. Women are underrepresented in engineering and technology (33.5%) but prevalent in medical and health sciences (61.7%) and agriculture (66.7%).[2]

The number of researchers per million inhabitants (in head counts) peaked at 1,867 in 2009 before receding to 1,300 in 2013, a lower level than over the period from 2001 to 2006. The number of researchers may be underestimated, as many Armenian researchers have secondary jobs in research.[2]

Higher education

Armenia has a well-established system of higher education. In 2015, it encompassed 22 state universities, 37 private universities, four universities established under intergovernmental agreements and nine branches of foreign universities. Universities in Armenia have a high degree of autonomy in formulating curricula and setting tuition fees.[2]

The Armenian government devoted a small share of GDP to higher education in 2013: 0.20%. This is much lower than the share allocated to higher education by Moldova (1.47%) and Ukraine (2.16%). Armenia's public education expenditure overall is also lower than that of most of its neighbours: 2.25% of GDP in 2013 (see figure).[2]

Armenia joined the Bologna Process in 2005. Within this process, universities have been working to align the standards and quality of their qualifications. With only a few exceptions, universities tend to focus almost exclusively on teaching and do not engage in, or encourage, research by staff.[2][4]

Armenia ranks 60th out of 122 countries for education – lagging somewhat behind Belarus and Ukraine but ahead of Azerbaijan and Georgia[5] Armenia ranks better for tertiary enrollment (44th out of 122 countries), with 25% of the workforce possessing tertiary education (see table below).Women make up one-third of PhD graduates (see table below). Armenia performs poorly, though, in the workforce and employment index (113th out of 122 countries), primarily due to high unemployment and low levels of employee training.[2]

Table: Higher education in Armenia, 2009-2012

Other countries are given for comparison

| Workforce with tertiary education | Tertiary enrolment rate | PhD or equivalent graduates, 2012 or closest year | ||||||||||

| Highest score 2009–2012 (%) | Change over five years (%) | Highest score 2009–2012 (% of age cohort) | Percentage point change over five years | Total | Women (%) | Natural sciences | Women (%) | Engineering | Women (%) | Health and welfare | Women (%) | |

| Armenia | 25 | 2.5 | 51 | 1.7 | 614−2 | 36−2 | 111−2 | 23−2 | 59−2 | 10−2 | 29−2 | 17−2 |

| Azerbaijan | 16 | -6.0 | 20 | 1.1 | 406 | 31 | 100 | 27 | 45 | 13 | 23 | 39 |

| Belarus | 24 | – | 92 | 21.3 | 1 216 | 53 | 186 | 51 | 215 | 24 | 188 | 50 |

| Georgia | 31 | -0.3 | 30 | -8.9 | 270 | 64 | 37 | 57 | 55 | 53 | 5 | 100 |

| Moldova | 25 | 5.0 | 40 | -1.1 | 405 | 60 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Turkey | 18 | 4.4 | 69 | 30.9 | 4 506 | 47 | 1 022 | 50 | 628 | 34 | 515 | 72 |

| Ukraine | 36 | 5.0 | 80 | 4.3 | 9 248 | 56 | 1 241 | 49 | 1 613 | 34 | 482 | 52 |

-n = refers to n years before reference year

Source: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (2015), Table 12.2, data from UNESCO Institute for Statistics

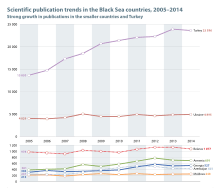

Scientific output

In 2014, Armenia had 232 scientific publications per million inhabitants catalogued in international journals, according to Thomson Reuters' Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded). This is more than the world average of 176 per million inhabitants. The number of scientific publications recorded in this database by Armenian scientists grew from 381 to 691 between 2005 and 2014. With a citation rate of 0.92 for their published articles between 2008 and 2012, Armenian scientists came close to the OECD average for this indicator: 1.08. Six out of ten (60%) Armenian articles had one or more foreign co-authors in 2014, twice the OECD average of 29% but similar to the ratio for Belarus (58%) and less than that for either Georgia (72%) or Moldova (71%).[2]

Like the other post-Soviet states, Armenia specializes in physics. As in Moldova and Ukraine, Armenian scientists collaborate most with their German peers but the Russian Federation also figures among Armenia's four closest collaborators in science and engineering.[2]

The value of Armenia's high-tech merchandise exports increased between 2008 and 2013 (see table). Between 2001 and 2010, Armenians submitted 14 patent applications to the European Patent Office and 37 to the US Patent and Trademark Office.[2]

Table: Armenia's high-tech merchandise exports, 2008 and 2013

Other countries are given for comparison

| Total in millions of US$* | Per capita in US$ | |||

| 2008 | 2013 | 2008 | 2013 | |

| Armenia | 7 | 9 | 2.3 | 3.1 |

| Azerbaijan | 6 | 42−1 | 0.7 | 4.4 −1 |

| Belarus | 422 | 769 | 44.1 | 82.2 |

| Georgia | 21 | 23 | 4.7 | 5.3 |

| Moldova | 13 | 17 | 3.6 | 4.8 |

| Turkey | 1 900 | 2 610 | 27.0 | 34.8 |

| Ukraine | 1 554 | 2 232 | 33.5 | 49.3 |

| Brazil | 10 823 | 9 022 | 56.4 | 45.0 |

| Russian Federation | 5 208 | 9 103 | 36.2 | 63.7 |

| Tunisia | 683 | 798 | 65.7 | 72.6 |

-n = refers to n years before reference year

Source: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (2015), Table 12.2, data from UNESCO Institute for Statistics

See also

Sources

![]()

References

- Melkumian, M (2014). "Ways of enhancing Armenia's social and economic development (in Russian)". Mir Peremen. 3: 28–40.

- Erocal, Deniz; Yegorov, Igor (2015). Countries in the Black Sea basin. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. pp. 324–341. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- Third BSEC Action Plan on Cooperation in Science and Technology 2014-2018 (PDF). Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation. 2014.

- Review of Innovation Development in Armenia. Geneva and New York: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. 2014.

- The Human Capital Report. Geneva: World Economic Forum. 2013.