Schoharie Creek Bridge collapse

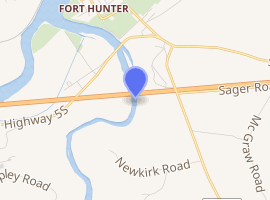

The Schoharie Creek Bridge was a New York State Thruway bridge over the Schoharie Creek near Fort Hunter and the Mohawk River in New York State. On April 5, 1987 it collapsed due to bridge scour at the foundations after a record rainfall. The collapse killed ten people. The replacement bridge was completed and fully open to traffic on May 21, 1988.[1]

Schoharie Creek Bridge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 42°55′51″N 74°16′41″W |

| Crosses | Schoharie Creek |

| Locale | Florida, Montgomery County, New York |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | plate girder bridge |

| Total length | 155 metres (509 ft) |

| History | |

| Opened | October 1955 |

| Collapsed | April 5, 1987 |

| |

The failure of the Schoharie Creek Bridge motivated improvement in bridge design and inspection procedures within New York and beyond.[2]

Bridge design and construction

The final design for the bridge was approved in January 1952 by the New York State Department of Transportation (previously named The New York State Department of Public Works). The design described a 155 meters (509 ft) crossing consisting of five simply supported spans with nominal lengths of 30.5 meters (100 ft), 33.5 m (110 ft), 36.6 m (120 ft), 33.5 m (110 ft), and 30.5 m (100 ft). The bridge was supported with pier frames along with abutments at each end. The pier frames were constructed of two slightly tapered columns with tie beams. The columns were fixed in place within a lightly reinforced plinth positioned on a shallow, reinforced spread footing. The spread footing was to be protected with a dry layer of riprap.[3]

The superstructure consisted of two longitudinal main girders with transverse floor beams. The skeleton of the bridge deck (200 millimeters (7.9 in) thick) was made up of steel stringers.

Construction began on February 11, 1953 by B. Perini and Sons, Inc.

Service

The bridge was partially opened during the summer of 1954 before construction was completed. The Schoharie Creek Bridge (NY 1020940, New York State bridge identification number), began full service beginning in October 1954.

In the spring and summer of 1955, the pier plinths began to show vertical cracks ranging from 3 to 5 mm (0.12 to 0.20 in), as a result of high tensile stresses in the concrete plinth. Almost a year later, on October 16, 1955, the bridge was damaged by a flood. In 1957, plinth reinforcement was added to each of the four piers.

Collapse

On the morning of April 5, 1987, during a high spring flood, the Schoharie Creek Bridge collapsed. A snowmelt combined with rainfall totaling 150 mm (5.9 in) produced an estimated 50-year flood on the creek.

Pier three was the first to collapse, which caused the progressive collapse of spans three and four. Ninety minutes later pier two and span two collapsed. Two hours later pier one and span one shifted. A National Transportation Safety Board investigation suggested that pier two collapsed because the wreckage of pier three and the two spans may have partially blocked the river, redirecting and increasing the velocity of the flow of water to pier two.

Six days later, 5 km (3.1 mi) upstream, a large section of the Mill Point Bridge collapsed. The bridge had been closed since the flood as a precaution, since inspection showed that its foundations had also been eroded.[4]

Casualties

At the time of the collapse, one car and one tractor-semitrailer were on the bridge. Before the road could be blocked off, three more cars drove into the gap. During the following three weeks, nine bodies were recovered from the river. The body of the 10th victim was recovered from the Mohawk River in July 1989.

Causes of failure

It was concluded that the bridge collapsed due to extensive scour under pier three. The foundation of the pier was bearing on erodible soil, consisting of layers of gravel, sand and silt, inter-bedded with folded and tilted till. This allowed high velocity flood waters to penetrate the bearing stratum. The area left around the footing was not filled with riprap stone, but instead was back-filled with erodible soil and topped off with dry riprap. Riprap protection, inspection, and maintenance were determined to have been inadequate.

The investigations showed that the scouring process under the piers began shortly after the bridge was built. At the time of the collapse, the upstream end of pier 3 fell into a scour hole approximately 3 meters (9.8 ft) deep. Investigators estimated that about 7.5 to 9 meters (25 to 30 ft) of the pier was undermined.

The design for the Schoharie Creek Bridge originally called for leaving sheet piles in place (which are used to keep water out of excavation areas during construction). The riprap would have filled the area left between the pier footings and the sheeting. However, this sheeting was not left in place.

Another reason for the collapse was the weight of the riprap. The design specification called for riprap with 50 percent of the stones heavier than 1.3 kilonewtons (290 lbf), and the remainder between 0.44 and 1.3 kN (99 and 292 lbf). Investigators found that heavier riprap weights of 4.4 to 6.7 kN (990 to 1,510 lbf) should have been specified.

Other considerations as to the cause of the collapse included design of the superstructure, quality of materials and construction, and inspection and maintenance. Investigations found that these factors did not contribute to the collapse.[5]

Twelve hours before the Schoharie Creek Bridge collapsed due to heavy rainfall, the rush of water through the Blenheim-Gilboa Pumped Storage Power Project 40 miles (64 km) upstream hit a historic high. To cope with the overload, the dam released water into the Schoharie Creek according to the rate at which it was entering the reservoir from upstream, adding to the load in the creek.[6]

See also

- List of bridge disasters

- Bridge scour

References

- Croyle, Johnathan (January 4, 2019). "On this date: Thruway bridge collapses into Schoharie Creek in 1987". syracuse.com. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Keary H. LeBeau and Sara J. Wadia-Fascetti. (2007). "Fault Tree Analysis of Schoharie Creek Bridge Collapse," Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities, Vol. 21, Issue 4, pp. 320-326. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0887-3828(2007)21:4(320)

- Jacob Feld, and Kenneth L. Carper (1997). "Construction Failure" John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-57477-5, ISBN 978-0-471-57477-4.

- "Hudson International Group - Schoharie Creek Bridge Collapse - Consultants and Engineers, Litigation Support and Insurance Investigation Services". Hudsonies.com. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- "Lessons from the Collapse of the Schoharie Creek Bridge". Eng.uab.edu. Archived from the original on October 7, 2006. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- Hevesi, Dennis (April 7, 1987). "Before Collapse,. A Record Water Rush - Nytimes.Com". New York State; Montgomery County (Ny); Schoharie Creek (Ny); Fort Hunter (Ny); Dewey, Thomas E, Thruway: New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

Further reading

- Boorstin, Robert O. (1987). "Bridge Collapses on the Thruway, Trapping Vehicles," The New York Times, April 6, 1987; Volume CXXXVI, No. 47,101.

- Huber, Frank. (1991). “Update: Bridge Scour.” Civil Engineering, ASCE, Vol. 61, No. 9, pp 62–63, September 1991.

- Levy, Matthys and Salvadori, Mario (1992). Why Buildings Fall Down. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

- National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). (1988). “Collapse of New York Thruway (I-90) Bridge over the Schoharie Creek, near Amsterdam, New York, April 5, 1987.” Highway Accident Report: NTSB/HAR-88/02, Washington, D.C.

- Springer Netherlands. "The collapse of the Schoharie Creek Bridge: a case study in concrete fracture mechanics", International Journal of Fracture, Volume 51, Number September 1, 1991.

- Palmer, R., and Turkiyyah, G. (1999). “CAESAR: An Expert System for Evaluation of Scour and Stream Stability.” National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Report 426, Washington D. C.

- Shepherd, Robin and Frost, J. David (1995). Failures in Civil Engineering: Structural, Foundation and Geoenvironmental Case Studies. American Society of Civil Engineers, New York, New York.

- Thornton, C. H., Tomasetti, R. L., and Joseph, L. M. (1988). “Lessons From Schoharie Creek,” Civil Engineering, Vol. 58, No.5, pp. 46–49, May 1988.

- Thornton-Tomasetti, P. C. (1987) “Overview Report Investigation of the New York State Thruway Schoharie Creek Bridge Collapse.” Prepared for: New York State Disaster Preparedness Commission, December 1987.

- Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc., and Mueser Rutledge Consulting Engineers (1987) “Collapse of Thruway Bridge at Schoharie Creek,” Final Report, Prepared for: New York State Thruway Authority, November 1987.

- Johnson, Diane M. The Schoharie.BookBaby, 2017. A novel.