Sator Square

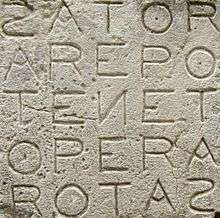

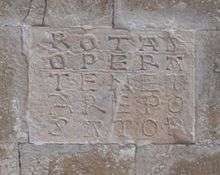

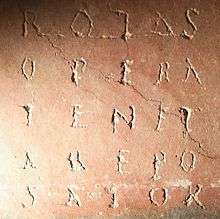

The Sator Square (or Rotas Square) is a word square containing a five-word Latin palindrome. The earliest form has ROTAS as the top line, but in time the version with SATOR on the top line became dominant. It is a five-by-five square made up of five 5-letter words, thus consisting of 25 letters in total, all derived from eight Latin letters: five consonants (S, T, R, P, N) and three vowels (A, E, O).

| R O T A S | S A T O R | |

| O P E R A | A R E P O | |

| T E N E T | T E N E T | |

| A R E P O | O P E R A | |

| S A T O R | R O T A S |

In particular, this is a square two-dimensional palindrome, and admits four symmetries (its symmetry group is the Klein four-group rather than the dihedral group of order 8 since adjacent sides of the square are not the same): identity, two diagonal reflections, and 180-degree rotation. As can be seen, the text may be read top-to-bottom, bottom-to-top, left-to-right, or right-to-left; and it may be rotated 180 degrees and still be read in all those ways.

The Sator Square is the earliest dateable two-dimensional palindrome. It was found in the ruins of Pompeii, at Herculaneum, a city buried in the ash of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. It consists of a sentence written in Latin: Sator Arepo tenet opera rotas. Its translation has been the subject of speculation with no clear consensus.

Other 2D palindrome examples may be found carved on stone tablets or pressed into clay before being fired.

Translation

- SATOR

- (nominative or vocative noun) (from serere=to sow) sower, planter, founder, progenitor (usually divine); originator; literally “seeder”.

- AREPO

- unknown, likely a proper name, either invented or, perhaps, of Egyptian origin, e.g. coded form of the name Harpocrates or Hor-Hap (Serapis).

- TENET

- (verb) (from tenere=to hold) he/she/it holds, keeps, comprehends, possesses, masters, preserves, sustains.

- OPERA

- (nominative, ablative or accusative noun) work, care, aid, labour, service, effort/trouble; (from opus): (nominative, accusative or vocative noun) works, deeds; (ablative) with effort.

- ROTAS

- (rotās, accusative plural of rota) wheels; (verb) you (singular) turn or cause to rotate.

One likely translation is "The farmer Arepo has [as] works wheels [a plough]"; that is, the farmer uses his plough as his form of work. Though not a significant sentence, it is grammatical; it can be read up and down, backwards and forwards. C. W. Ceram also reads the square boustrophedon (in alternating directions). But since word order is very free in Latin, the translation is the same. If the Sator Square is read boustrophedon, in reverse direction, the words become SATOR OPERA TENET, with the sequence reversed.[1]

Given that the Square’s Outer consonant string joined with the Square’s central letter produces S-T-R-N, and that SaTuRN was the Roman God of time-cycles, agriculture, and magic, this claim by The Museum of Witchcraft and Magic is especially relevant: “Sator may originally have been a Sacred Name of Saturn. The Roman scholar Marcus Terentius Varro (De Lingua Latina, 5.64) was of the opinion that the name Saturn had its origins in the verb sero (sow/beget), which the noun sator is derived from.”.[2] The theory is further affirmed when one notes that Saturn’s consort Ops, from which “opus” comes, the plural form of which is “opera”.

The word arepo is a hapax legomenon, appearing nowhere else in Latin literature. Its similarity with arrepo, from ad repo, 'I creep towards', may be coincidental. Most of those who have studied the Sator Square agree that it is a proper name, either an adaptation of a non-Latin word or most likely a name invented specifically for this sentence. Jerome Carcopino thought that it came from a Celtic, specifically Gaulish, word for plough. David Daube argued that it represented a Hebrew or Aramaic rendition of the Greek Ἄλφα ω, or "Alpha-Omega" (cf. Revelation 1:8) by early Christians. J. Gwyn Griffiths contended that it came, via Alexandria, from the attested Egyptian name Ḥr-Ḥp, which he took to mean "the face of Apis".[3] An origin in Graeco-Roman Egypt was also advocated by Miroslav Marcovich, who maintains that Arepo is a Latinized abbreviation of Harpocrates, god of the rising sun, in some places called Γεωργός `Aρπον, which Marcovich suggests corresponds to Sator Arepo.[4] If one accepts that one or more deity names is encoded into the Sator square then this word square could be considered an example of a theophoric mandala.

If arepo is taken to be in the second declension, the -o ending could put the word in the ablative case, giving it a meaning of "by means of [arepus]." Using this definition of arepo and the boustrophedon reading order produces the text "The sower works for mastery by turning the wheel."

Reading ox-plough style from the outer S corner into the central N would produce the sentence: SAT ORO PER ATEN (Sufficiently I pray through Aten).

Turning to the diagonals, we see N-P-R or Neper (mythology), the Egyptian god of grain. And the other diagonal is N-R-S or Nereus, the Roman Old Man of the Sea. The central letter N is pronounced Nun (letter) in Hebrew, and has the meaning of fish. But in Egyptian cosmogology Nun or Nu (mythology) is the primordial waters, source of all, father of all the gods. The vertical and horizontal NET sequence spells Neith, the Egyptian goddess of creation and weaving, and prime creator deity. When we combine the full inner lines we get TENET, which puns into TINNIT (a.k.a. Tanit), the Great Mother Goddess of Carthage and the equivalent of Astarte (aSTaRTe). If we use the NETOR turn we see the Coptic word for “god”, Neter.[5] If we turn in the other direction we get NETAS, the accusative feminine plural of “woven”.

Appearances

The oldest datable representation of the Sator Square was found in the ruins of Pompeii. Others have been found in excavations under the church of S. Maria Maggiore in Rome,[6] at Corinium (modern Cirencester in England) and Dura-Europos (in modern Syria).

The Benedictine Abbey of St Peter ad Oratorium, near Capestrano, in Abruzzo, Italy, has a marble square inscription of the Sator Square. An example discovered at the Valvisciolo Abbey, also in central Italy, has the letters forming five concentric rings, each one divided into five sectors. Other Sator Squares are on the exterior wall of the Duomo of Siena, Italy, and on a memorial.[7]

Outside of Italy, an example found in a group of stones in the grounds of Rivington Church reads SATOR AREPO TENET OPERA ROTAS. The stone is one of a group thought to have come from a local private chapel in Anderton, Lancashire.[8] An example is found inserted in a wall of the old district of Oppède, in France's Luberon. There is a Sator Square in the museum at Conimbriga (near Coimbra in Portugal), excavated on the site.

There is one known occurrence of the phrase on the rune stone Nä Fv1979;234 from Närke, Sweden, dated to the 14th century. It reads "sator arepo tenet" (untranscribed: "sator ¶ ar(æ)po ¶ tænæt).[9] It also occurs in two inscriptions from Gotland (G 145 M and G 149 M), in both of which the whole palindrome is written.[9]

"Sator Square" appears as a geographical location in the city/state of Anhk-Morpork in Terry Pratchett's Discworld series of books.

The Sator Square also appears in the Catweazle series of books created by Richard Carpenter.

Christian associations

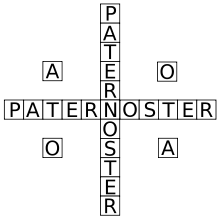

By repositioning the letters around the central letter Ν (en), a Greek cross can be made that reads Pater Noster (Latin for "Our Father", the first two words of the "Lord's Prayer") both vertically and horizontally. The remaining letters – two each of A and O – can be taken to represent the concept of Alpha and Omega, a reference in Christianity to the omnipresence of God. Thus the square might have been used as a covert symbol for early Christians to express their presence to each other.[10]

In addition to the equilateral TENET cross within the square, and the PATER NOSTER equilateral cross which can be formed from the letters in the square, one can find a Maltese cross in the square by joining the A, E, O vowels in each quadrant in a V formation and joining them to the central N. Astonishingly the feminine goddess of eternity in ancient Roman religion and thus the consort of Aeon, Aeternitas, is found in the Sator Square and also forms a cross: ETOR-NETAS.

In the Latin Vulgate version on Ezekiel one finds the words “rota” and “opera” in 1:16, as well as the plural form “rotae”. This is a central Merkabah mysticism text which speaks of wheels within wheels. The outer wheel of the square spins as SATOROTA or ROTASATO (O: oh, sat: sufficient, rota: wheel) while the inner wheel spins as PERE (per: through, throughout) or REPE (rēpe: you crawl). Ezekiel 1:18 mentions that the wheel’s “rims were immense, circled with eyes, and interesting on the outer portion of the square the letter A can be considered to be a depiction of an eye viewed from a horizontal angle while the letter O considered a depiction of an open eye viewed from the front.

An example of the Sator Square found in Manchester dating to the 2nd century AD has been interpreted according to this model as one of the earliest pieces of evidence of Christianity in Britain.[11]

The Coptic Prayer of the Virgin in Bartos describes how that Christ was crucified with five nails, which were named Sator, Arepo, Tenet, Opera and Rotas.[12] This reading of the words consequently entered the Ethiopic tradition where they became the names of the wounds of Christ.[13] In Ethiopian tradition the words are slightly altered, with SADOR being the lance wound, ALADOR being the right hand wound, DANAT being the left hand wound, ADERA being the right foot wound, and RODAS being the left foot wound. These 5 words are prayed on each knot of an 41 count Ethiopian mequetaria (prayer rope).[14]

In Cappadocia, in the time of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (913–959), the shepherds of the Nativity story are called SATOR, AREPON, and TENETON, while a Byzantine bible of an earlier period conjures out of the square the baptismal names of the three Magi, ATOR, SATOR, and PERATORAS.[15]

Other authorities believe the Sator Square was Mithraic or Jewish in origin, because it is not likely that Pompeii had a large Christian population in 79 AD and the symbolism inferred as Christian and the use of Latin in Christianity is not attested until later.[16] James H. Charlesworth is of the view that the Sator Square is sacred to Asclepius, the serpent god, and thus sacred to all serpent gods. He suggests that one possible prayer form of this square might be: “SATOR-ROTAS (O Creator - you who cause [all] to rotate.) OPERA-AREPO (with effort I crawl toward [you].) TENET-TENET-TENET-TENET (Maintain [the rotations from the north, the east, the south and the west].)[17]

Exorcism prayers can also be derived from rearranging the 25 letters of the square:

- RETRO SATANA, TOTO OPERE ASPER

- ORO TE PATER, ORO TE PATER, SANAS

- O PATER, ORES PRO AETATE NOSTRA

- ORA, OPERARE, OSTENTA TE PASTOR[18]

Punning with the square reveals many more spiritual themes in the square, such as:

- Pardon: PER-TEN (per- + dōnō)

- Repent: REPENETO (re- + poeniteo)

Employing non-Latin languages known by the 1st century Romans is also useful in reading the square’s letter configurations. For instance, in the two corners, when Sanskrit is phonetically employed, one finds the sacred “body” (ROOP/rup or POOR/pur) and “blood” (ASRA)[19]

Magical uses

The Sator Square is a four-times palindrome, and some people have attributed magical properties to it, considering it one of the broadest magical formulas in the West. An article on the square from The Saint Louis Medical and Surgical Journal, vol. 76, reports that palindromes were viewed as being immune to tampering by the devil, who would become confused by the repetition of the letters, and hence their popularity in magical use. The same principle, alongside the above "Paternoster cross", is also present in the Greek magical palindrome: ΑΒΛΑΝΑΘΑΝΑΛΒΑ, which probably derives from the Hebrew or Aramaic אב לן את, meaning "Thou art our father".

The square has reportedly been used in folk magic for various purposes, including putting out fires (the spell is "TO EXTINGUISH FIRE WITHOUT WATER" in John George Hohman's Long Lost Friend), removing jinxes and fevers, to protect cattle from witchcraft,[20] and against fatigue when traveling.[21] It is sometimes claimed it must be written upon a certain material, or else with a certain type of ink to achieve its magical effect. It is often placed on houses and barns for protection.

In regards to magic, it is also worth considering the masculine and feminine polarities which can be invoked when working/ploughing/weaving with the square. In Latin the -TOR suffix is a masculine indicator while -TAS is a feminine indicator. Also interesting is that in Latin, applying the D/T soundshift to the word SATOR and dropping the beginning S aspirate produces ADOR, which can be read as “adiūrō” (to conjure) or “adōrō” (to adore).

The Sator Square is used in both Pennsylvania Dutch communities as part of their powwow medicine and in Russian Orthodox Old Believer communities.[22][23]

See also

- Abracadabra, sometimes written in form of triangle

- Cave canem, another Pompeian phrase

- Christian symbolism

- Isopsephy, for further Pompeian graffiti

- Magic square

- Memes

- Mithraic Mysteries

- Word square

References

- Ceram (1958), p. 30.

- "'Arepo' in the Magic 'Sator' Square'": J. Gwyn Griffiths, The Classical Review, New Series, Vol. 21, No. 1, March 1971, pp. 6–8.

- "Sator arepo = ΓΕΩΡΓΟΣ ̔ΑΡΠΟΝ(ΚΝΟΥΦΙ) ΑΡΠΩΣ (geōrgos arpon[knouphi] arpōs), arpo(cra), harpo(crates)": Miroslav Marcovich, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik Bd. 50 (1983), pp. 155-171, jstor.com

- Ancient Egyptian deities#Definition

- Magi, Filippo (1972). Il calendario dipinto sotto S. Maria Maggiore. Libreria Editrice Vaticana. ISBN 9788820943790.

- Findagrave.com

- John Rawlinson, About Rivington, Chorley: Nelson Brothers Limited, 1969, p. 42.

- "amnordisk runtextdatabas". Runforum Uppsala. 2010-12-20. Archived from the original on 2012-05-25. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- Robert Milburn; Robert Leslie Pollington Milburn (1988). Early Christian art and architecture. University of California Press. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-520-06326-6. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- Shotter (2004), pp. 129–130.

- James De Quincey Donehoo (1903). The Apocryphal and legendary life of Christ: being the whole body of the Apocryphal gospels and other extra canonical literature which pretends to tell of the life and words of Jesus Christ, including much matter which has not before appeared in English. In continuous narrative form, with notes, Scriptural references, prolegomena, and indices. Macmillan. pp. 350–. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- . Ludolf, Hiob (1691). Iobi Ludolfi alias Lutholf dicti ad suam historiam Adthiopicam adhanc editam commentarius. p. 351. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- Ethiopian Orthodox Prayers

- Fishwick, D. 1959. An Early Christian Cryptogram? Link: http://www.umanitoba.ca/colleges/st_pauls/ccha/Back%20Issues/CCHA1959/Fishwick.htm

- Ferguson, Everett (1 September 2003). Backgrounds of early Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 590–. ISBN 978-0-8028-2221-5. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- The Good and Evil Serpent: How a Universal Symbol Became Christianized by James H. Charlesworth; The Anchor Yale Bible Reference Library: March 23, 2010

- Duncan Fishwick, An Early Christian Cryptogram? (HTML)

- Northvegr.org Archived August 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- The Gentleman's Magazine vol. 258, 1885.

- “POWWOWING IN PENNSYLVANIA: HEALING RITUALS OF THE DUTCH COUNTRY”, Glencairn Museum News, Number 2, 2017.

- Ilia Rodov, “Kabbalistic Traces in a Russian Old-Believer Painting”, Wolf Moskovich, Roman Mnich and Renata Tarasiuk (editors), 'Galicia, Bukovina and Other Borderlands in Eastern and Central Europe', Jews and Slavs Volume 23, Jerusalem-Siedlce: 2013.

Bibliography

- Shotter, David (1993). Romans and Britons in North-West England. Lancaster: Centre for North-West Regional Studies. ISBN 1-86220-152-8.

- Ceram, C. W. (1958). The March of Archaeology. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. L.C.Catalog no. 58-10977.

- James H. Charlesworth, The Good and Evil Serpent, Anchor Yale (2010)

- Walter Moeller, The Mithraic Origin and Meanings of the Rotas-Sator Square, Brill (2015)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sator Arepo Tenet Opera Rotas. |

- Pérez-Rubín, Carlos (2004). "The sunken ruins of Pompeii and an age-old enigmatic specimen of roman incidental Epigraphy" (PDF). Documenta & Instrumenta. 2: 173–192.

- Duncan Fishwick, An Early Christian Cryptogram? (HTML)

- Sator Square, inscribed, Article; the article uses: "Rotas square"

- "Section of Page and Eloise's Memorial website related to the Sator Square, 1995 (HTML)"

- Magic Square Museum: the first Second Life museum about Magic Square. The first flow is about Sator Square. Vulcano (89,35,25)

- The Museum of Witchcraft, 1583 – CHARM: TALISMAN