Sargasso Sea

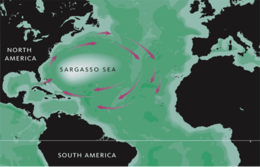

The Sargasso Sea (/sɑːrˈɡæsoʊ/) is a region of the Atlantic Ocean bounded by four currents forming an ocean gyre.[1] Unlike all other regions called seas, it has no land boundaries.[2][3][4] It is distinguished from other parts of the Atlantic Ocean by its characteristic brown Sargassum seaweed and often calm blue water.[1]

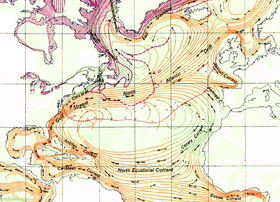

The sea is bounded on the west by the Gulf Stream, on the north by the North Atlantic Current, on the east by the Canary Current, and on the south by the North Atlantic Equatorial Current, a clockwise-circulating system of ocean currents termed the North Atlantic Gyre. It lies between 70° and 40° W, and 20° to 35° N, and is approximately 1,100 km wide by 3,200 km long (700 by 2,000 miles).[5][6] Bermuda is near the western fringes of the sea.[7]

All of the currents deposit the marine plants and refuse which they are carrying into this sea, yet the ocean water in the Sargasso Sea is distinctive for its deep blue color and exceptional clarity, with underwater visibility of up to 61 m (200 ft).[8] It is also a body of water that has captured the public imagination, and so is seen in a wide variety of literary and artistic works and in popular culture.[9]

History

The naming of the Sargasso Sea for its Sargassum seaweed dates from the early 15th-century Portuguese explorations of the Azores Islands and of the large "volta do mar" (the North Atlantic gyre), around and west of the archipelago, where the seaweed was often present.[10] However, the sea may have been known to earlier mariners, as a poem by the late 4th-century author Rufus Festus Avienus describes a portion of the Atlantic as being covered with seaweed, citing a now-lost account by the 5th-century BC Carthaginian Himilco the Navigator.[11]

According to the Muslim cartographer Muhammad al-Idrisi the Mugharrarūn (Arabic: المغررون, "the adventurers") sent by the Almoravid sultan Ali ibn Yusuf (1084 - 1143), led by his admiral Ahmad ibn Umar, reached a part of the ocean covered by seaweed,[12] identified by some as the Sargasso Sea.[13]

In 1846, Edward Forbes hypothesized a post-Miocene land mass extending westward from Europe into the Atlantic:

If this land existed it did not extend to America (for the fossils of the Miocene of America are representative & not identical): where then was the edge or coastline of it, Atlantic-wards? Look at the form & constancy of the great fucus-bank & consider that it is a Sargassum bank.

— Edward Forbes, from the Darwin Correspondence Project[14]

Ecology

The Sargasso Sea is home to seaweed of the genus Sargassum, which floats en masse on the surface. The sargassum is not a threat to shipping, and historic incidents of sailing ships being trapped there are due to the often calm winds of the horse latitudes.[15]

The Sargasso Sea plays a role in the migration of catadromous eel species such as the European eel, the American eel, and the American conger eel. The larvae of these species hatch within the sea and as they grow they travel to Europe or the East Coast of North America. Later in life, the matured eel migrates back to the Sargasso Sea to spawn and lay eggs. It is also believed that after hatching, young loggerhead sea turtles use currents such as the Gulf Stream to travel to the Sargasso Sea, where they use the sargassum as cover from predators until they are mature.[16][17] The sargassum fish is a species of frogfish specially adapted to blend in among the sargassum seaweed.[18]

In the early 2000s, the Sargasso Sea was sampled as part of the Global Ocean Sampling survey, to evaluate its diversity of microbial life through metagenomics. Contrary to previous theories, results indicated the area has a wide variety of prokaryotic life.[19]

Pollution

Owing to surface currents, the Sargasso accumulates a high concentration of non-biodegradable plastic waste.[20][21] The area contains the huge North Atlantic garbage patch.[22]

Several nations and nongovernmental organizations have united to protect the Sargasso Sea.[23] These organizations include the Sargasso Sea Commission[24] established 11 March 2014 by the governments of the Azores (Portugal), Bermuda (United Kingdom), Monaco, United Kingdom and the United States.

Bacteria that consume plastic have been found in the plastic-polluted waters of the Sargasso Sea; however, it is unknown whether these bacteria ultimately clean up poisons or simply spread them elsewhere in the marine microbial ecosystem. Plastic debris can absorb toxic chemicals from ocean pollution, potentially poisoning anything that eats it.[25]

Depictions in popular culture

The Sargasso Sea is often portrayed in literature and the media as an area of mystery.[9]

The Sargasso Sea features in classic fantasy stories by William Hope Hodgson, such as his novel The Boats of the "Glen Carrig" (1907), Victor Appleton's Don Sturdy novel Don Sturdy in the Port of Lost Ships: Or, Adrift in the Sargasso Sea, and several related short stories.[26] Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas describes the Sargasso Sea and gives an account of its formation.[27]

The Sargasso Sea is frequently (but erroneously) depicted in fiction as a dangerous area where ships are mired in weed for centuries, unable to escape. The Doc Savage novel The Sargasso Ogre, published in 1933, takes place in the Sargasso where descendants of Elizabethan pirates still live. A similar story appears in Green Lantern (vol. 1) No. 3 (Spring 1942), "The Living Graveyard of the Sea," which refers to it as a supposedly mythical place. Here the descendants of many different kinds of ships live in utopian harmony, until they are attacked by Nazis who wish to use it to their advantage. The premiere episode of Jonny Quest, "Mystery of the Lizard Men", involves a spy ring operating in the Sargasso, underneath the (nonexistent) derelict ships. Hammer Film Productions' 1968 film The Lost Continent (based on a 1938 Dennis Wheatley novel, Uncharted Seas), depicts travelers lost in a Sargasso Sea infested with carnivorous seaweed, giant crustaceans, and descendants of Spanish conquistadores ruling over other trapped people, descendants of those mired in the weed centuries before. These depictions are parodied in The Venture Bros. season 1 episode "Ghosts of the Sargasso", set in the overlapping areas of the Sargasso Sea and the Bermuda Triangle, which depicts supposed pirates whose ship was stuck in the sargassum for a decade and the ghost of the pilot of an experimental aircraft which crashed into the sea in 1969.[28]

Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) by Jean Rhys is a rewriting of Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre from Bertha Mason's point of view.[29]

The Sargasso Sea is referenced in the Dead Can Dance song "All in Good Time" from their 2012 album Anastasis.[30]

The Sargasso Sea is referenced in the refrain of Andrew Bird's April 2016 song "Left Handed Kisses" (featuring singer Fiona Apple)."[31][32]

One-man band Lemon Demon refers to the "Super" Sargasso Sea in the song "Touch-Tone Telephone," released on his 2016 album "Spirit Phone"[33]

The Sargasso Sea is referenced in the 2019 episode "Silky Love"[34] of the Radiolab podcast as the location where eels migrate and procreate.

References

- Stow, Dorrik A.V. (2004). Encyclopedia of the Oceans. Oxford University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0198606871. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- NGS Staff (27 September 2011). "Sea". nationalgeographic.org. National Geographic Society. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

...a sea is a division of the ocean that is enclosed or partly enclosed by land...

- Karleskint, George (2009). Introduction to Marine Biology. Boston MA: Cengage Learning. p. 47. ISBN 9780495561972. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- "What's the Difference between an Ocean and a Sea?". Ocean Facts. Silver Spring MD: National Ocean Service (NOS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 25 March 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2017 – via OceanService.NOAA.gov.

- "Sargasso Sea". oceanfdn.org. The Ocean Foundation. 14 September 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- Weatheritt, Les (2000). Your First Atlantic Crossing: A Planning Guide for Passagemakers (4th ed.). London: Adlard Coles Nautical. ISBN 9781408188088. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- Webster, George (31 May 2011). "Mysterious waters: from the Bermuda Triangle to the Devil's Sea". CNN. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- "Sargasso Sea". World Book. 1958. 15. Field Enterprises Educational Corp.

- Heller, Ruth (2000). A Sea Within a Sea: Secrets of the Sargasso. Price Stern Sloan. ISBN 978-0-448-42417-0.

- "The Sargasso Sea". BBC – Homepage. BBC. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- Various Authors (2016). The Historians' History of the World in Twenty-Five Volumes: Israel, India, Persia, Phoenicia, Minor Nations of Western Asia, Vol. II. Library of Alexandria. ISBN 9781465608017.

- الإدريسي, أبي عبد الله محمد بن محمد/الشريف (1 January 2020). نزهة المشتاق في اختراق الآفاق (in Arabic). Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiyah دار الكتب العلمية. ISBN 978-2-7451-6563-3.

- Fromherz, Allen James, ‘The Near West’, page 133, 2016, Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9781474426404

- "Darwin Correspondence Project". darwinproject.ac.uk. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- "Sargasso". Straight Dope. August 2002.

- "Turtles return home after UK stay". BBC News. 30 June 2008. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Satellites track turtle 'lost years'". BBC News. 5 March 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2019/06/sargasso-sea-north-atlantic-gyre-supports-ocean-life/

- Venter, JC; Remington, K; Heidelberg, JF; et al. (April 2004). "Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the Sargasso Sea". Science. 304 (5667): 66–74. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.124.1840. doi:10.1126/science.1093857. PMID 15001713.

- "The Trash Vortex (2008)". Greenpeace. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- "The trash vortex (2014)". Greenpeace.

- Wilson, Stiv J. (16 June 2010). "Atlantic Garbage Patch". HuffPost. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- Shaw, David (27 May 2014). "Protecting the Sargasso Sea". Science & Diplomacy. 3 (2).

- "Sargasso Sea Commission". sargassoalliance.org. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Gwyneth Dickey Zaikab (March 2011). "Marine microbes digest plastic". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.191.

- Hodgeson, William Hope (2011). The Collected Fiction of William Hope Hodgson: Boats of Glen Carrig & Other Nautical Adventures. New York: Night Shade Books. ISBN 978-1-892389-39-8.

- Verne, Jules (1870). 20,000 Leagues Under the Seas. Translated by Butcher, William (2001 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192828392.

- "Ghosts of the Sargasso". The Venture Bros. Season 1. Episode 6. 11 September 2004. Adult Swim.

- Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea (1966)

- https://genius.com/Dead-can-dance-all-in-good-time-lyrics

- andrewbirdmusic (14 March 2016), Andrew Bird – Left Handed Kisses (ft. Fiona Apple) [OFFICIAL VIDEO], retrieved 30 December 2017

- Yeow Kai Chai (6 April 2016). "A sea of love, then a hot mess". The Straits Times. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Demon, Lemon. "Touch Tone Telephone". Bandcamp. Bandcamp. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Kielty, Matt; Bressler, Becca. "Silky Love – Radiolab". WNYC Studios. WNYC Studios. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

External links

| Look up Sargasso Sea in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |