Santorini

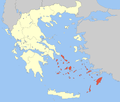

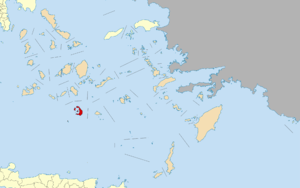

Santorini (Greek: Σαντορίνη, pronounced [sandoˈrini]), officially Thira (Greek: Θήρα [ˈθira]) and classic Greek Thera (English pronunciation /ˈθɪərə/), is an island in the southern Aegean Sea, about 200 km (120 mi) southeast of Greece's mainland. It is the largest island of a small, circular archipelago, which bears the same name and is the remnant of a volcanic caldera. It forms the southernmost member of the Cyclades group of islands, with an area of approximately 73 km2 (28 sq mi) and a 2011 census population of 15,550. The municipality of Santorini includes the inhabited islands of Santorini and Therasia, as well as the uninhabited islands of Nea Kameni, Palaia Kameni, Aspronisi and Christiana. The total land area is 90.623 km2 (34.990 sq mi).[2] Santorini is part of the Thira regional unit.[3]

Santorini / Thira Σαντορίνη / Θήρα

| |

|---|---|

Seal | |

Santorini / Thira Location within the region  | |

| Coordinates: 36°25′N 25°26′E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | South Aegean |

| Regional unit | Thira |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Antonis Sigalas |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 90.69 km2 (35.02 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Municipality | 15,550 |

| • Municipality density | 170/km2 (440/sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 14,005 |

| Community | |

| • Population | 1,857 (2011) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 847 00, 847 02 |

| Area code(s) | 22860 |

| Vehicle registration | EM |

| Website | www.thira.gr |

The island was the site of one of the largest volcanic eruptions in recorded history: the Minoan eruption (sometimes called the Thera eruption), which occurred about 3,600 years ago at the height of the Minoan civilization.[4] The eruption left a large caldera surrounded by volcanic ash deposits hundreds of metres deep. It may have led indirectly to the collapse of the Minoan civilization on the island of Crete, 110 km (68 mi) to the south, through a gigantic tsunami. Another popular theory holds that the Thera eruption is the source of the legend of Atlantis.[5]

It is the most active volcanic centre in the South Aegean Volcanic Arc, though what remains today is chiefly a water-filled caldera. The volcanic arc is approximately 500 km (310 mi) long and 20 to 40 km (12 to 25 mi) wide. The region first became volcanically active around 3-4 million years ago, though volcanism on Thera began around 2 million years ago with the extrusion of dacitic lavas from vents around Akrotiri.

Names

Santorini was named by the Latin Empire in the thirteenth century, and is a reference to Saint Irene, from the name of the old cathedral in the village of Perissa – the name Santorini is a contraction of the name Santa Irini.[4] Before then, it was known as Kallístē (Καλλίστη, "the most beautiful one"), Strongýlē (Greek: Στρογγύλη, "the circular one"),[6] or Thēra. The name Thera was revived in the nineteenth century as the official name of the island and its main city, but the colloquial name Santorini is still in popular use.

Municipality

The present municipality of Thera (officially: "Thira", Greek: Δήμος Θήρας),[7][8] which covers all settlements on the islands of Santorini and Therasia, was formed at the 2011 local government reform, by the merger of the former Oia and Thera municipalities.[3]

Oia is now called a Κοινότητα (community), within the municipality of Thera, and it consists of the local subdivisions (Greek: τοπικό διαμέρισμα) of Therasia and Oia.

The municipality of Thera includes an additional 12 local subdivisions on Santorini island: Akrotiri, Emporio, Episkopis Gonia, Exo Gonia, Imerovigli, Karterados, Megalohori, Mesaria, Pyrgos Kallistis, Thera (the seat of the municipality), Vothon, and Vourvoulos.[9]

Economy

Santorini's primary industry is tourism. Agriculture also forms part of its economy, and the island sustains a wine industry, based on the indigenous Assyrtiko grape variety. White varieties also include Athiri and Aidani, whereas red varieties include mavrotragano and mandilaria.

Geology

Geological setting

The Cyclades are part of a metamorphic complex that is known as the Cycladic Massif. The complex formed during the Miocene and was folded and metamorphosed during the Alpine orogeny around 60 million years ago. Thera is built upon a small, non-volcanic basement that represents the former non-volcanic island, which was approximately 9 by 6 km (5.6 by 3.7 mi). The basement rock is primarily composed of metamorphosed limestone and schist, which date from the Alpine Orogeny. These non-volcanic rocks are exposed at Mikro Profititis Ilias, Mesa Vouno, the Gavrillos ridge, Pyrgos, Monolithos, and the inner side of the caldera wall between Cape Plaka and Athinios.

The metamorphic grade is a blueschist facies, which results from tectonic deformation by the subduction of the African Plate beneath the Eurasian Plate. Subduction occurred between the Oligocene and the Miocene, and the metamorphic grade represents the southernmost extent of the Cycladic blueschist belt.

Volcanism

Volcanism on Santorini is due to the Hellenic Trench subduction zone southwest of Crete. The oceanic crust of the northern margin of the African Plate is being subducted under Greece and the Aegean Sea, which is thinned continental crust. The subduction compels the formation of the Hellenic arc, which includes Santorini and other volcanic centres, such as Methana, Milos, and Kos.[10]

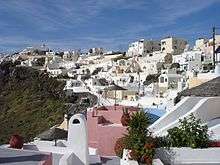

The island is the result of repeated sequences of shield volcano construction followed by caldera collapse.[11] The inner coast around the caldera is a sheer precipice of more than 300 metres (980 ft) drop at its highest, and exhibits the various layers of solidified lava on top of each other, and the main towns perched on the crest. The ground then slopes outwards and downwards towards the outer perimeter, and the outer beaches are smooth and shallow. Beach sand colour depends on which geological layer is exposed; there are beaches with sand or pebbles made of solidified lava of various colours: such as the Red Beach, the Black Beach and the White Beach. The water at the darker coloured beaches is significantly warmer because the lava acts as a heat absorber.

The area of Santorini incorporates a group of islands created by volcanoes, spanning across Thera, Thirasia, Aspronisi, Palea, and Nea Kameni.

Santorini has erupted many times, with varying degrees of explosivity. There have been at least twelve large explosive eruptions, of which at least four were caldera-forming.[10] The most famous eruption is the Minoan eruption, detailed below. Eruptive products range from basalt all the way to rhyolite, and the rhyolitic products are associated with the most explosive eruptions.

The earliest eruptions, many of which were submarine, were on the Akrotiri Peninsula, and active between 650,000 and 550,000 years ago.[10] These are geochemically distinct from the later volcanism, as they contain amphiboles.

Over the past 360,000 years there have been two major cycles, each culminating with two caldera-forming eruptions. The cycles end when the magma evolves to a rhyolitic composition, causing the most explosive eruptions. In between the caldera-forming eruptions are a series of sub-cycles. Lava flows and small explosive eruptions build up cones, which are thought to impede the flow of magma to the surface.[10] This allows the formation of large magma chambers, in which the magma can evolve to more silicic compositions. Once this happens, a large explosive eruption destroys the cone. The Kameni islands in the centre of the lagoon are the most recent example of a cone built by this volcano, with much of them hidden beneath the water.

Minoan eruption

The devastating volcanic eruption of Thera around 1600 B.C. has become the most famous single event in the Aegean before the fall of Troy. It may have been one of the largest volcanic eruptions on Earth in the last few thousand years, with an estimated VEI (volcanic explosivity index) of 6 according to the last studies published in 2006, confirming the prior values. The violent eruption was centred on a small island just north of the existing island of Nea Kameni in the centre of the caldera; the caldera itself was formed several hundred thousand years ago by the collapse of the centre of a circular island, caused by the emptying of the magma chamber during an eruption. It has been filled several times by ignimbrite since then, and the process repeated itself, most recently 21,000 years ago. The northern part of the caldera was refilled by the volcano, then collapsed once more during the Minoan eruption. Before the Minoan eruption, the caldera formed a nearly continuous ring with the only entrance between the tiny island of Aspronisi and Thera; the eruption destroyed the sections of the ring between Aspronisi and Therasia, and between Therasia and Thera, creating two new channels.

On Santorini, a deposit of white tephra thrown from the eruption is found lying up to 60 m (200 ft) thick, overlying the soil marking the ground level before the eruption, and forming a layer divided into three fairly distinct bands indicating different phases of the eruption. Archaeological discoveries in 2006 by a team of international scientists revealed that the Santorini event was much more massive than previously thought; it expelled 61 cubic kilometres (15 cu mi) of magma and rock into the Earth's atmosphere, compared to previous estimates of only 39 cubic kilometres (9.4 cu mi) in 1991,[12][13] producing an estimated 100 cubic kilometres (24 cu mi) of tephra. Only the Mount Tambora volcanic eruption of 1815, the 181 AD eruption of Lake Taupo, and possibly Baekdu Mountain's 946 AD eruption have released more material into the atmosphere during the past 5,000 years.

Speculation on an Exodus connection

In The Parting of the Sea: How Volcanoes, Earthquakes, and Plagues Shaped the Exodus Story,[14] geologist Barbara J. Sivertsen seeks to establish a link between the eruption of Santorini (c. 1600 BC) and the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt in the Bible.

A 2006 documentary film by Simcha Jacobovici, The Exodus Decoded,[15] postulates that the eruption of the Santorini Island volcano (referred to as c. 1500 BC) caused all the biblical plagues described against Egypt. The documentary presents this date as corresponding to the time of the Biblical Moses. The film asserts that the Hyksos were the Israelites and that some of them may have originally been from Mycenae. The film also suggests that these original Mycenaean Israelites fled Egypt (which they had in fact ruled for some time) after the eruption, and went back to Mycenae. The Pharaoh of the Exodus is identified with Ahmose I. Rather than crossing the Red Sea, Jacobovici argues a marshy area in northern Egypt known as the Reed Sea would have been alternately drained and flooded by tsunamis caused by the caldera collapse, and could have been crossed during the Exodus.

Jacobovici's assertions in The Exodus Decoded have been extensively criticized by religious and other scholars.[16][17] In a 2013 book on this connection, Thera and the Exodus, a dissident from the consensus Riaan Booysen, tries to support Jacobovici's theory and claims the pharaoh of the Exodus to be Amenhotep III and the biblical Moses as Crown Prince Thutmose, Amenhotep's first-born son and heir to his throne.[18]

Speculation on an Atlantis connection

Archaeological, seismological, and vulcanological evidence[19][20][21] has been presented linking the Atlantis myth to Santorini. Speculation suggesting that Thera/Santorini was the inspiration for Plato's Atlantis began with the excavation of Akrotiri in the 1960s, and gained increased currency as reconstructions of the island's pre-eruption shape and landscape frescos located under the ash both strongly resembled Plato's description. The possibility has been more recently popularized by television documentaries such as The History Channel programme Lost Worlds (episode "Atlantis"), the Discovery Channel's Solving History with Olly Steeds, and the BBC's Atlantis, The Evidence, which suggests that Thera is Plato's Atlantis.[22]

Post-Minoan volcanism

Post-Minoan eruptive activity is concentrated on the Kameni islands, in the centre of the lagoon. They have been formed since the Minoan eruption, and the first of them broke the surface of the sea in 197 BC[10] Nine subaerial eruptions are recorded in the historical record since that time, with the most recent ending in 1950.

In 1707 an undersea volcano breached the sea surface, forming the current centre of activity at Nea Kameni in the centre of the lagoon, and eruptions centred on it continue—the twentieth century saw three such, the last in 1950. Santorini was also struck by a devastating earthquake in 1956. Although the volcano is dormant at the present time, at the current active crater (there are several former craters on Nea Kameni), steam and carbon dioxide are given off.

Small tremors and reports of strange gaseous odours over the course of 2011 and 2012 prompted satellite radar technological analyses and these revealed the source of the symptoms; the magma chamber under the volcano was swelled by a rush of molten rock by 10 to 20 million cubic metres between January 2011 and April 2012, which also caused parts of the island's surface to rise out of the water by a reported 8 to 14 centimetres.[23] Scientists say that the injection of molten rock was equivalent to 20 years’ worth of regular activity.[23]

Climate

Santorini has a semi-arid climate (Bsh in the Köppen climate classification) with Mediterranean characteristics.[24] Total rainfall averages 371 mm (14.6 in) per year. In the summer season, strong winds can also be observed.[25]

| Climate data for Santorini (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 14 (57) |

14 (57) |

16 (61) |

18 (64) |

23 (73) |

27 (81) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

26 (79) |

23 (73) |

19 (66) |

15 (59) |

21 (70) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12 (54) |

12 (54) |

14 (57) |

16 (61) |

20 (68) |

24 (75) |

26 (79) |

26 (79) |

24 (75) |

21 (70) |

17 (63) |

13 (55) |

19 (66) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 10 (50) |

10 (50) |

11 (52) |

13 (55) |

17 (63) |

21 (70) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

21 (70) |

18 (64) |

14 (57) |

11 (52) |

16 (61) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 71 (2.8) |

43 (1.7) |

40 (1.6) |

16 (0.6) |

11 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

7 (0.3) |

0 (0) |

11 (0.4) |

38 (1.5) |

59 (2.3) |

75 (3.0) |

371 (14.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 11 | 59 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 7 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 10 |

| Source: holiday-weather.com[26] | |||||||||||||

History

Minoan Akrotiri

Excavations starting in 1967 at the Akrotiri site under the late Professor Spyridon Marinatos have made Thera the best-known Minoan site outside of Crete, homeland of the culture. The island was not known as Thera at this time. Only the southern tip of a large town has been uncovered, yet it has revealed complexes of multi-level buildings, streets, and squares with remains of walls standing as high as eight metres, all entombed in the solidified ash of the famous eruption of Thera. The site was not a palace-complex as found in Crete, but neither was it a conglomeration of merchants' warehousing, as its excellent masonry and fine wall-paintings show. A loom-workshop suggests organized textile weaving for export. This Bronze Age civilization thrived between 3000 and 2000 BC, reaching its peak in the period between 2000 and 1630 BC.[27]

Many of the houses in Akrotiri are major structures, some of them three stories high. Its streets, squares, and walls were preserved in the layers of ejecta, sometimes as tall as eight metres, indicating this was a major town. In many houses stone staircases are still intact, and they contain huge ceramic storage jars (pithoi), mills, and pottery. Noted archaeological remains found in Akrotiri are wall paintings or frescoes, which have kept their original colour well, as they were preserved under many metres of volcanic ash. The town also had a highly developed drainage system and, judging from the fine artwork, its citizens were clearly sophisticated and relatively wealthy people.

Pipes with running water and water closets found at Akrotiri are the oldest such utilities discovered. The pipes run in twin systems, indicating that Therans used both hot and cold water supplies; the origin of the hot water probably was geothermic, given the volcano's proximity. The dual pipe system, the advanced architecture, and the apparent layout of the Akrotiri find resemble Plato's description of the legendary lost city of Atlantis, further indicating the Minoans as the culture which primarily inspired the Atlantis legend.[5]

Fragmentary wall-paintings at Akrotiri lack the insistent religious or mythological content familiar in Classical Greek décor. Instead, the Minoan frescoes depict "Saffron-Gatherers", who offer their crocus-stamens to a seated lady, perhaps a goddess. Crocus has been discovered to have many medicinal values including the relief of menstrual pain. This has led many archaeologists to believe that the fresco of the saffron/crocus gatherers is a coming of age fresco dealing with female pubescence. In another house are two antelopes, painted with a kind of confident, flowing, decorative, calligraphic line, the famous fresco of a fisherman with his double strings of fish strung by their gills, and the flotilla of pleasure boats, accompanied by leaping dolphins, where ladies take their ease in the shade of light canopies, among other frescoes.

The well preserved ruins of the ancient town are often compared to the spectacular ruins at Pompeii in Italy. The canopy covering the ruins collapsed in an accident in September 2005, killing one tourist and injuring seven more. The site was closed for almost seven years while a new canopy was built. The site was re-opened in April 2012.

The oldest signs of human settlement are Late Neolithic (4th millennium BC or earlier), but c. 2000–1650 BC Akrotiri developed into one of the Aegean's major Bronze Age ports, with recovered objects that came not just from Crete, but also from Anatolia, Cyprus, Syria, and Egypt, as well as from the Dodecanese and the Greek mainland.

Dating of the Bronze Age eruption

The Minoan eruption provides a fixed point for the chronology of the second millennium BC in the Aegean, because evidence of the eruption occurs throughout the region and the site itself contains material culture from outside. The eruption occurred during the "Late Minoan IA" period at Crete and the "Late Cycladic I" period in the surrounding islands.

Archaeological evidence, based on the established chronology of Bronze Age Mediterranean cultures, dates the eruption to around 1500 BC.[28] These dates, however, conflict with radiocarbon dating which indicates that the eruption occurred at about 1645–1600 BC.[29] For those, and other, reasons, the date of the eruption is disputed. For discussion, see Minoan eruption#Eruption dating.

Ancient period

.jpg)

Santorini remained unoccupied throughout the rest of the Bronze Age, during which time the Greeks took over Crete. At Knossos, in a LMIIIA context (14th century BC), seven Linear B texts while calling upon "all the gods" make sure to grant primacy to an elsewhere-unattested entity called qe-ra-si-ja and, once, qe-ra-si-jo. If the endings -ia[s] and -ios represent an ethnic suffix, then this means "The One From Qeras[os]". If the initial consonant were aspirated, then *Qhera- would have become "Thera-" in later Greek. "Therasia" and its ethnikon "Therasios" are both attested in later Greek; and, since -sos was itself a genitive suffix in the Aegean Sprachbund, *Qeras[os] could also shrink to *Qera. An alternate view takes qe-ra-si-ja and qe-ra-si-jo as proof of androgyny, and applies this name by similar arguments to the legendary seer, Tiresias, but these views are not mutually exclusive. If qe-ra-si-ja was an ethnikon first, then in following him/her/it the Cretans also feared whence it came.[30]

Probably after what is called the Bronze Age collapse, Phoenicians founded a site on Thera. Herodotus reports that they called the island Callista and lived on it for eight generations.[31] In the 9th century BC, Dorians founded the main Hellenic city on Mesa Vouno, 396 m (1,299 ft) above sea level. This group later claimed that they had named the city and the island after their leader, Theras. Today, that city is referred to as Ancient Thera.

In his Argonautica, written in Hellenistic Egypt in the 3rd century BC, Apollonius Rhodius includes an origin and sovereignty myth of Thera being given by Triton in Libya to the Greek Argonaut Euphemus, son of Poseidon, in the form of a clod of dirt. After carrying the dirt next to his heart for several days, Euphemus dreamt that he nursed the dirt with milk from his breast, and that the dirt turned into a beautiful woman with whom he had sex. The woman then told him that she was a daughter of Triton named Kalliste, and that when he threw the dirt into the sea it would grow into an island for his descendants to live on. The poem goes on to claim that the island was named Thera after Euphemus' descendant Theras, son of Autesion, the leader of a group of refugee settlers from Lemnos.

The Dorians have left a number of inscriptions incised in stone, in the vicinity of the temple of Apollo, attesting to pederastic relations between the authors and their lovers (eromenoi). These inscriptions, found by Friedrich Hiller von Gaertringen, have been thought by some archaeologists to be of a ritual, celebratory nature, because of their large size, careful construction and – in some cases – execution by craftsmen other than the authors. According to Herodotus,[32] following a drought of seven years, Thera sent out colonists who founded a number of cities in northern Africa, including Cyrene. In the 5th century BC, Dorian Thera did not join the Delian League with Athens; and during the Peloponnesian War, Thera sided with Dorian Sparta, against Athens. The Athenians took the island during the war, but lost it again after the Battle of Aegospotami. During the Hellenistic period, the island was a major naval base for Ptolemaic Egypt.

Medieval and Ottoman period

As with other Greek territories, Thera then was ruled by the Romans. When the Roman Empire was divided, the island passed to the eastern side of the Empire which today is known as the Byzantine Empire. According to George Cedrenus, the volcano erupted again in the summer of 727, the tenth year of the reign of Leo III the Isaurian.[33] He writes: "In the same year, in the summer, a vapour like an oven's fire boiled up for days out of the middle of the islands of Thera and Therasia from the depths of the sea, and the whole place burned like fire, little by little thickening and turning to stone, and the air seemed to be a fiery torch." This terrifying explosion was interpreted as a divine omen against the worship of religious icons [34][35] and gave the Emperor Leo III the Isaurian the justification he needed to begin implementing his Iconoclasm policy.

The name "Santorini" first appears c. 1153-1154 in the work of the Muslim geographer al-Idrisi, as "Santurin", from the island's patron saint, Saint Irene.[36] After the Fourth Crusade, it became a lordship of the Venetian Barozzi family, starting with Jacopo I Barozzi, until it was annexed to the Duchy of Naxos in c. 1335 by Niccolo Sanudo.[37] In 1318–1331 and 1345–1360 it was raided by the Turkish principalities of Menteshe and Aydın, but did not suffer much damage.[36] From the 15th century on, the suzerainty of the Republic of Venice over the island was recognized in a series of treaties by the Ottoman Empire, but this did not stop Ottoman raids, until it was captured by the Ottoman admiral Piyale Pasha in 1576, as part of a process of annexation of most remaining Latin possessions in the Aegean.[36] It became part of the semi-autonomous domain of the Sultan's Jewish favourite, Joseph Nasi. Santorini retained its privileged position in the 17th century, but suffered in turn from Venetian raids during the frequent Ottoman–Venetian wars of the period, even though there were no Muslims on the island.[36]

Santorini was captured briefly by the Russians under Alexey Orlov during the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774, but returned to Ottoman control after. Following the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence on the Greek mainland in March 1821, in May Santorini followed suit, although the local Catholic population had its reservations. The island became part of the fledgling Greek state, rebelled against Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias in 1831, and became definitively part of the independent Kingdom of Greece in 1832, with the Treaty of Constantinople.[36]

The island is still home to a Catholic community and the seat of a Catholic bishopric.

World War II

During the Second World War, Santorini was occupied in 1941 by Italian forces, and in 1943 by those of the Germans. In 1944, the German and Italian garrison on Santorini was raided by a group of British Special Boat Service Commandos, killing most of its men. Five locals were later shot in reprisal, including the mayor.[38][39]

Modern Santorini

Tourism

Santorini's primary industry is tourism, particularly in the summer months. The expansion of tourism has resulted in the growth of the economy and population. Akrotiri is a major archaeological site, with ruins from the Minoan era. Santorini was ranked the world's top island by many magazines and travel sites, including the Travel+Leisure Magazine,[40] the BBC,[41] as well as the US News.[42] An estimated 2 million tourists visit annually.[43]

The island's pumice quarries have been closed since 1986, in order to preserve the caldera. In 2007, the cruise ship MS Sea Diamond ran aground and sank inside the caldera. As of 2019, Santorini is a particular draw for Asian couples who come to Santorini to have pre-wedding photos taken against the backdrop of the island's landscape.[44]

Aridity

%2C_Greece-2.jpg)

Santorini has no rivers, and water is scarce. Until the early 1990s locals filled water cisterns from the rain that fell on roofs and courts, from small springs, and with imported assistance from other areas of Greece. In recent years a desalination plant has provided running, yet non-potable, water to most houses. Since rain is rare on the island from mid-spring to mid-autumn, many plants depend on the scant moisture provided by the common, early morning fog condensing on the ground as dew.

Agriculture

.jpg)

Because of its unique ecology and climate, and especially its volcanic ash soil, Santorini is home to unique and prized produce.

Wine industry

The island remains the home of a small, but flourishing, wine industry, based on the indigenous grape variety, Assyrtiko, with auxiliary cultivations of two other Aegean varietals, Athiri and Aidani. The vines are extremely old and resistant to phylloxera (attributed by local winemakers to the well-drained volcanic soil and its chemistry), so the vines needed no replacement during the great phylloxera epidemic of the late 19th century. In their adaptation to their habitat, such vines are planted far apart, as their principal source of moisture is dew, and they often are trained in the shape of low-spiralling baskets, with the grapes hanging inside to protect them from the winds.

The viticultural pride of the island is the sweet and strong Vinsanto (Italian: "holy wine") (Visanto), a dessert wine made from the best sun-dried Assyrtiko, Athiri, and Aidani grapes, and undergoing long barrel aging (up to twenty or twenty-five years for the top cuvées). It matures to a sweet, dark amber-orange, unctuous dessert wine that has achieved worldwide fame, possessing the standard Assyrtiko aromas of citrus and minerals, layered with overtones of nuts, raisins, figs, honey and tea.

White wines from the island are extremely dry with a strong, citrus scent and mineral and iodide salt aromas contributed by the ashy volcanic soil, whereas barrel aging gives to some of the white wines a slight frankincense aroma, much like Vinsanto. It is not easy to be a winegrower in Santorini; the hot and dry conditions give the soil a very low productivity. The yield per hectare is only 10 to 20% of the yields that are common in France or California. The island's wines are standardised and protected by the "Vinsanto" and "Santorini" OPAP designations of origin.[45]

A brewery, the Santorini Brewing Company, began operating out of Santorini in 2011, based in the island's wine region.[46]

Architecture

The traditional architecture of Santorini is similar to that of the other Cyclades, with low-lying cubical houses, made of local stone and whitewashed or limewashed with various volcanic ashes used as colours. The unique characteristic is the common utilisation of the hypóskapha: extensions of houses dug sideways or downwards into the surrounding pumice. These rooms are prized because of the high insulation provided by the air-filled pumice, and are used as living quarters of unique coolness in the summer and warmth in the winter. These are premium storage space for produce, especially for wine cellaring: the Kánava wineries of Santorini.

When strong earthquakes struck the island in 1956, half the buildings were completely destroyed and a large number suffered repairable damage. The underground dwellings along the ridge overlooking the caldera, where the instability of the soil was responsible for the great extent of the damage, needed to be evacuated. Most of the population of Santorini had to emigrate to Piraeus and Athens.[47]

Notable people

- Themison of Thera

- Spyros Markezinis, politician

- Mariza Koch, singer

- Giannis Alafouzos, former president of Panathinaikos F.C.

Popular culture

The island was featured in The 2005 film ”The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants“.

Santorini Film Festival held annually at the open air cinema, Cinema Kamari in Santorini.[48]

American hip hop musician Rick Ross has a song titled Santorini Greece, and its 2017 music video was shot on the island.

Transport

Land

Bus services link Fira to most parts of the island.[49]

Ports

Santorini has two ports: Athinios (Ferry Port) and Skala (Old Port).[50] Cruise ships anchor off Skala and passengers are transferred by local boatmen to shore at Skala where Fira is accessed by cable car, on foot or by donkey.[51] Tour boats depart from Skala for Nea Kameni and other Santorini destinations.[52]

Airport

Santorini is one of the few Cyclades Islands with a major airport, which lies about 6 km (4 mi) southeast of downtown Thera. The main asphalt runway (16L-34R) is 2,125 metres (6,972 feet) in length, and the parallel taxiway was built to runway specification (16R-34L). It can accommodate Boeing 757, Boeing 737, Airbus 320 series, Avro RJ, Fokker 70, and ATR 72 aircraft. Scheduled airlines include the new Olympic Air, Aegean Airlines, and Ryanair, with chartered flights from other airlines during the summer, and with transportation to and from the air terminal available through buses, taxis, hotel car-pickups and rental cars.

Towns and villages

- Akrotiri

- Ammoudi

- Athinios

- Emporio

- Finika

- Fira

- Firostefani

- Imerovigli

- Kamari

- Karterados

- Messaria

- Monolithos

- Oia

- Perissa

- Pyrgos Kallistis

- Vothonas

- Vourvoulos

References

Notes

- "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-21.

- Kallikratis law Greece Ministry of Interior (in Greek)

- Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. pp. 336–337. ISBN 978-0-89577-087-5.

- Charles Pellegrino, Unearthing Atlantis – An Archaeological Odyssey Vintage Books, 1991

- C. Doumas (editor). Thera and the Aegean world: papers presented at the second international scientific congress, Santorini, Greece, August 1978. London, 1978. ISBN 0-9506133-0-4

- "Δήμος Θήρας, the official municipal government website" (in Greek). Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- "Municipality of Thira, English language version of the official municipal government website". Archived from the original on 2012-07-27. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- "Spreadsheet table of all administrative subdivisions in Greece, and their population as of the 18 March 2001 census" (Excel). Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Interior, Decentralization and E-government. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- Druitt, Timothy H.; L. Edwards; R.M. Mellors; D.M. Pyle; R.S.J. Sparks; M. Lanphere; M. Davies; B. Barriero (1999). Santorini Volcano. Geological Society Memoir. 19. London: Geological Society. ISBN 978-1-86239-048-5.

- "Geology of Santorini". Volcano Discovery.

- URI.edu, URI Department of Communications and Marketing

- NationalGeographic.com, "Atlantis" Eruption Twice as Big as Previously Believed, Study Suggests.

- Sivertsen, Barbara J (2009). The Parting of the Sea: How Volcanoes, Earthquakes, and Plagues Shaped the Story of the Exodus. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13770-4.

- "The Exodus Decoded Office Website". Theexodusdecoded.net. Retrieved 2010-10-24.

- "Debunking "The Exodus Decoded"". September 20, 2006. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- "The Exodus Decoded: An Extended Review". 19 Dec 2006. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- Booysen, Riaan (2013), Thera and the Exodus, O Books, ISBN 978-1-78099-449-9.

- "Santorini Eruption (~1630 BC) and the legend of Atlantis". Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- Vergano, Dan (2006-08-27). "Ye gods! Ancient volcano could have blasted Atlantis myth". USA Today. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- Lilley, Harvey (20 April 2007). "The wave that destroyed Atlantis". BBC Timewatch. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- Atlantis – The Evidence by Bettany Hughes BBC.co.uk, Timewatch

- Brian Handwerk (12 September 2012). "Santorini Bulges as Magma Balloons Underneath". National Geographic Society.

- "Weather in Santorini". Santorini.net.

- "Santorini information, traditional products, beaches, volcano and villages, Attractions, Events – Santorini holidays 2014". www.greektouristguides.com. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- "Weather Averages for Santorini, Greece". holiday-weather.com. Retrieved 2016-09-26.

- TheModernAntiquarian.com, C. Michael Hogan, Akrotiri, The Modern Antiquarian (2007).

- Warren, Peter M. (2006). "The Date of the Thera Eruption in Relation to Aegean-Egyptian Interconnections and the Egyptian Historical Chronology". In Czerny E.; Hein I.; Hunger H.; Melman D.; Schwab A. (eds.). Timelines: Studies in Honour of Manfred Bietak. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, 149. Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium: Peeters. pp. 2: 305–21. ISBN 978-90-429-1730-9.

- Manning, Stuart W.; Ramsey, C.B.; Kutschera, W.; Higham, T.; Kromer, B.; Steier, P. and Wild, E.M. (2006). "Chronology for the Aegean Late Bronze Age 1700–1400 B.C." Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 312 (5773): 565–69. Bibcode:2006Sci...312..565M. doi:10.1126/science.1125682. PMID 16645092. Retrieved 2007-03-10.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- TheraFoundation.org, Minoan Qe-Ra-Si-Ja. The Religious Impact of the Thera Volcano on Minoan Crete. Archived 2006-06-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Hist. IV.147

- Hist. IV.149–165

- George Cedrenus, Σύνοψις ἱστορίων, Vol I, p. 795.

- Θεοφάνης Ομολογητής, Χρονογραφία σελ. 621-622 : «ος [ο Λέων] την κατ’ αυτού θείαν οργήν υπέρ εαυτού λογισάμενος». Νικηφόρος σελ. 64 : «Ταύτά φασιν ακούσαντα τον βασιλέα υπολαμβάνειν θείας οργής είναι μηνύματα».

- Ιωάννης Παναγιωτόπουλος, «Το ηφαίστειο της Θήρας και η Eικονομαχία». Θεολογία 80 (2009), 235-253

- Savvides, A. (1997). "Santurin Adasi̊". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume IX: San–Sze. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 20. ISBN 90-04-10422-4.

- Marina Koumanoudi, “The Latins in the Aegean after 1204: Interdependence and Interwoven Interests,” in Urbs capta: The Fourth Crusade and its Consequences, 2005, p.263

- Mortimer, Gavin. The Special Boat Squadron in WW2, Osprey, 2013, ISBN 1782001891.

- Lewis, Damien. Churchill's Secret Warriors, Quercus 2014, ISBN 1848669178.

- "2011 World's Best Awards". Travel+Leisure. Archived from the original on 2011-07-12. Retrieved 2011-07-16.

- "World's Best Islands". BBC. Retrieved 2011-12-01.

- "World's Best Island". US News. Retrieved 2014-04-01.

- Smith, Helena (28 August 2017). "Santorini's popularity soars but locals say it has hit saturation point". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- Horowitz, Jason; Boushnak, Laura (6 August 2019). "The Bride, the Groom and the Greek Sunset: A Perfect Wedding Picture". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- "Greece Santorini History". www.greecesantorini.com. Retrieved 2015-11-03.

- "Greece's Handcrafted Beers Hit the Spot | GreekReporter.com". greece.greekreporter.com. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- "Restoration, Reconstruction and Simulacra" (PDF).

- "Santorini Film Festival". FilmFreeway. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- "Santorini Public Buses". www.ktel-santorini.gr.

- Santorini Port Authority http://www.santorini-port.com

- "Greek island accused of abusing its star attraction: donkeys". DW.COM. 2019-07-08. Retrieved 2019-07-11.

- Santorini Port Authority http://www.santoriniport.com

Bibliography

- Forsyth, Phyllis Y.: Thera in the Bronze Age, Peter Lang Pub Inc, New York 1997. ISBN 0-8204-4889-3

- Friedrich, W., Fire in the Sea: the Santorini Volcano: Natural History and the Legend of Atlantis, translated by Alexander R. McBirney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000.

- History Channel's "Lost Worlds: Atlantis" archeology series. Features scientists Dr. J. Alexander MacGillivray (archeologist), Dr. Colin F. MacDonald (archaeologist), Professor Floyd McCoy (vulcanologist), Professor Clairy Palyvou (architect), Nahid Humbetli (geologist) and Dr. Gerassimos Papadopoulos (seismologist)

Further reading

- Bond, A. and Sparks, R. S. J. (1976). "The Minoan eruption of Santorini, Greece". Journal of the Geological Society of London, Vol. 132, 1–16.

- Doumas, C. (1983). Thera: Pompeii of the ancient Aegean. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Pichler, H. and Friedrich, W.L. (1980). "Mechanism of the Minoan eruption of Santorini". Doumas, C. Papers and Proceedings of the Second International Scientific Congress on Thera and the Aegean World II.

External links

- TheraFoundation.org, The Eruption of Thera: Date and Implications

- Santorini.gr, Thira (Santorini) Municipality Official WebSite

- CGS.Illinois.edu , Was the Bronze Age Volcanic Eruption of Thira (Santorini) a Megacatastrophe? A Geological/Archeological Detective Story, Grant Heiken, Independent consultant, author, geologist (retired) Los Alamos National Laboratory; lecture presented at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, sponsored by CGS.Illinois.edu, Center for Global Studies and CAS.UIUC.edu, Center for Advanced Study

- NewAdvent.org, Thera (Santorin) – Catholic Encyclopedia article

- URI.edu: Santorini Eruption much larger than previously thought

- Moving Postcards: Santorini

- Older eruption history at Santorini

- Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants and Bang Bang: Santorini In Pop Culture

- The castles of Santorini

- Photos of Santorini

- The sacred Rock

.svg.png)