Samuel David Luzzatto

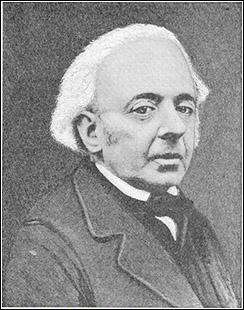

Samuel David Luzzatto (Italian pronunciation: [ˈsamwel ˈdavid lutˈtsato]; Hebrew: שמואל דוד לוצאטו) was an Italian Jewish scholar, poet, and a member of the Wissenschaft des Judentums movement. He is also known by his Hebrew acronym, Shadal (שד"ל).

Samuel David Luzzatto | |

|---|---|

Luzzato, from an 1865 engraving. | |

| Born | 22 August 1800 |

| Died | 30 September 1865 (aged 65) |

| Nationality | Italian |

Early life

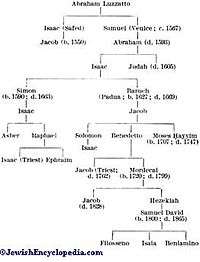

Luzzatto was born at Trieste on 22 August 1800 (Rosh Hodesh, 1 Elul, 5560), and died at Padua on 30 September 1865 (Yom Kippur, 10 Tishrei 5626). While still a boy, he entered the Talmud Torah of his native city, where besides Talmud, in which he was taught by Abraham Eliezer ha-Levi , chief rabbi of Trieste and a distinguished pilpulist, he studied ancient and modern languages and science under Mordechai de Cologna, Leon Vita Saraval, and Raphael Baruch Segré, whose son-in-law he later became. He studied the Hebrew language also at home, with his father, who, though a turner by trade, was an eminent Talmudist.

Luzzatto manifested extraordinary ability from his very childhood, such that while reading the Book of Job at school, he formed the intention to write a commentary thereon, considering the existing commentaries to be deficient. In 1811 he received, as a prize, Montesquieu's "Considérations sur les Causes de la Grandeur des Romains," etc., which contributed much to the development of his critical faculties. Indeed, his literary activity began in that very year, for it was then that he undertook to write a Hebrew grammar in Italian; translated into Hebrew the life of Aesop; and wrote exegetical notes on the Pentateuch.[1] The discovery of an unpublished commentary on the Targum of Onkelos induced him to study Aramaic.[2]

At the age of thirteen Luzzatto was withdrawn from school, attending only the Talmud lectures of Abraham Eliezer ha-Levi. While reading the Ein Yaakov he came to the conclusion that the vowels and accents did not exist in the time of the Talmudists, and that the Zohar, speaking as it does of vowels and accents, must necessarily be of later composition. He propounded this theory in a pamphlet which was the origin of his later work "Vikkuach 'al ha-Kabbalah."

In 1814 there began a most trying time for Luzzatto. As his mother died in that year, he had to do the housework, including cooking, and to help his father in his work as a turner. Nevertheless, by the end of 1815 he had composed thirty-seven poems, which form a part of his "Kinnor Na'im," and in 1817 had finished his "Ma'amar ha-Niqqud," a treatise on the vowels. In 1818 he began to write his "Torah Nidreshet," a philosophico-theological work of which he composed only twenty-four chapters, the first twelve being published in the "Kokhebe Yiẓḥaḳ," vols. 16-17, 21-24, 26, and the remainder translated into the Italian language by M. Coen-Porto and published in "Mosé," i-ii. In 1879 Coen-Porto published a translation of the whole work in book form. In spite of his father's desire that he should learn a trade, Luzzatto had no inclination for one, and in order to earn his livelihood he was obliged to give private lessons, finding pupils with great difficulty on account of his timidity. From 1824, in which year his father died, he had to depend entirely upon himself. Until 1829 he earned a livelihood by giving lessons and by writing for the "Bikkure ha-'Ittim"; in that year he was appointed professor at the rabbinical college of Padua.

Critical treatment of the Bible

At Padua, Luzzatto had a much larger scope for his literary activity, as he was able to devote all his time to literary work. Besides, while explaining certain parts of the Bible to his pupils he wrote down all his observations. Luzzatto was the first Jewish scholar to turn his attention to Syriac,[3] considering a knowledge of this language of significant importance for the understanding of the Targum. His letter published in Kirchheim's Karme Shomeron shows his thorough acquaintance with Samaritan.

He was also one of the first Jews who permitted themselves to emend the text of the Old Testament (others, though with a lesser degree of originality, include Samson Cohen Modon[4][5] and Manassa of Ilya[6]); many of his emendations met with the approval of critical scholars of the day. Through a careful examination of the Book of Ecclesiastes, Luzzatto came to the conclusion that its author was not Solomon, but someone who lived several centuries later and whose name was "Kohelet". The author, Luzzatto thinks, ascribed his work to Solomon, but his contemporaries, having discovered the forgery, substituted the correct name "Kohelet" for "Solomon" wherever the latter occurred in the book. While the notion of the non-Solomonic authorship of Ecclesiastes is today accepted by secular scholars, most modern scholars do not ascribe the work to an actual individual named "Kohelet", but rather regard the term as a label or designation of some kind, akin to the Septuagint's translation of "Preacher."

As to the Book of Isaiah, in spite of the prevalent opinion that chapters 40-66 were written after the Babylonian captivity, Luzzatto maintained that the whole book was written by Isaiah. He felt that one of the factors that pushed scholars to post-date the latter portion of the book stemmed from a denial of the possibility of prophetic prediction of distant future events, and therefore was a heretical position. Difference of opinion on this point was one of the causes why Luzzatto, after having maintained a friendly correspondence with Rapoport, turned against the latter. Another reason for the interruption of his relations with the chief rabbi of Prague was that Luzzatto, though otherwise on good terms with Jost, could not endure the latter's extreme rationalism. He consequently requested Rapoport to cease his relations with Jost; but Rapoport, not knowing Luzzatto personally, ascribed the request to arrogance.

Views on philosophy

Luzzatto was a warm defender of Biblical and Talmudical Judaism; and his strong opposition to philosophical Judaism (or "atticism" as he terms it) brought him many opponents among his contemporaries. However, his antagonism to philosophy was not the result of fanaticism nor of lack of understanding. He claimed to have read during twenty-four years all the ancient philosophers, and that the more he read them the more he found them deviating from the truth. What one approves the other disproves; and so the philosophers themselves go astray and mislead students. Another of Luzzatto's main criticisms of philosophy is its inability to engender compassion towards other humans, which is the focus of traditional Judaism (or, as Luzzatto terms it, "Abrahamism").

For this reason, while praising Maimonides as the author of the Mishneh Torah, Luzzatto blames him severely for being a follower of the Aristotelian philosophy, which (Luzzatto says) brought no good to himself while causing much evil to other Jews.[7] Luzzatto also attacked Abraham ibn Ezra, declaring that Ibn Ezra's works were not the products of a scientific mind, and that as it was necessary for him in order to secure a livelihood to write a book in every town in which he sojourned, the number of his books corresponded with the number of towns he visited. Ibn Ezra's material, he declared, was always the same, the form being changed sometimes slightly, and at other times entirely.[8] Luzzatto's pessimistic opinion of philosophy made him naturally the adversary of Spinoza, whom he attacked on more than one occasion.

Luzzatto's works

During his literary career of more than fifty years, Luzzatto wrote a great number of works and scholarly correspondences in Hebrew, Italian, German and French. Besides he contributed to most of the Hebrew and Jewish periodicals of his time. His correspondence with his contemporaries is both voluminous and instructive; there being hardly any subject in connection with Judaism on which he did not write.

In Hebrew

- Kinnor Na'im, collection of poems. Vol. i., Vienna, 1825; vol. ii., Padua, 1879.

- Kinah, elegy on the death of Abraham Eliezer ha-Levi. Triest, 1826.

- Ohev Ger, guide to the understanding of Targum Onkelus, with notes and variants; accompanied by a short Syriac grammar and notes on and variants in the Targum of Psalms. Vienna, 1830.

- Hafla'ah sheba-'Arakhin of Isaiah Berlin, edited by Luzzatto, with notes of his own. Part i., Breslau, 1830; part ii., Vienna, 1859.

- Seder Tannaim va-Amoraim, revised and edited with variants. Prague, 1839.

- Betulat Bat Yehudah, extracts from the diwan of Judah ha-Levi, edited with notes and an introduction. Prague, 1840.

- Avnei Zikkaron, seventy-six epitaphs from the cemetery of Toledo, followed by a commentary on Micah by Jacob Pardo, edited with notes. Prague, 1841.

- Beit ha-Otzar, collection of essays on the Hebrew language, exegetical and archeological notes, collectanea, and ancient poetry. Vol. i., Lemberg, 1847; vol. ii., Przemysl, 1888; vol. iii., Cracow, 1889.

- Ha-Mishtaddel, scholia to the Pentateuch. Vienna, 1849.

- Vikuach 'al ha-Kabbalah, dialogues on Cabala and on the antiquity of punctuation. Göritz, 1852.

- Sefer Yesha'yah, the Book of Isaiah edited with an Italian translation and a Hebrew commentary. Padua, 1855-67.

- Mevo, a historical and critical introduction to the Maḥzor. Leghorn, 1856.

- Diwan, eighty-six religious poems of Judah ha-Levi corrected, vocalized, and edited, with a commentary and introduction. Lyck, 1864.

- Yad Yosef, a catalogue of the Library of Joseph Almanzi. Padua, 1864.

- Ma'amar bi-Yesodei ha-Dikduk, a treatise on Hebrew grammar. Vienna, 1865.

- Ḥerev ha-Mithappeket, a poem of Abraham Bedersi, published for the first time with a preface and a commentary at the beginning of Bedersi's "Hotam Tokhnit." Amsterdam, 1865.

- Commentary on the Pentateuch. Padua, 1871.

- Perushei Shedal, commentary on Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Proverbs, and Job. Lemberg, 1876.

- Nahalat Shedal, in two parts; the first containing a list of the Geonim and Rabbis, and the second one of the payyetanim and their piyyutim. Berlin, 1878-79.

- Yesodei ha-Torah, a treatise on Jewish dogma. Przemysl, 1880.

- Tal Orot, a collection of eighty-one unpublished piyyutim, amended. Przemysl, 1881.

- Iggerot Shedal, 301 letters, published by Isaiah Luzzatto and prefaced by David Kaufmann. Przemysl, 1882.

- Peninei Shedal (see below). Przemysl, 1883

In Italian

- Prolegomeni ad una Grammatica Ragionata della Lingua Ebraica. Padua, 1836. (Annotated English edition by A.D. Rubin, 2005.[9])

- Il Giudaismo Illustrato. Padua, 1848.

- Calendario Ebraico. Padua, 1849.

- Lezioni di Storia Giudaica. Padua, 1852.

- Grammatica della Lingua Ebraica. Padua, 1853.

- Italian translation of Job. Padua, 1853.

- Discorsi Morali agli Studenti Israeliti. Padua, 1857.

- Opere del De Rossi. Milan, 1857.

- Italian translation of the Pentateuch and Hafṭarot. Triest, 1858-60.

- Lezioni di Teologia Morale Israelitica. Padua, 1862.

- Lezioni di Teologia Dogmatica Israelitica. Triest, 1864.

- Elementi Grammaticali del Caldeo Biblico e del Dialetto Talmudico. Padua, 1865. Translated into German by Krüger, Breslau, 1873; into English by Goldammer, New York, 1876; and the part on the Talmudic dialect, into Hebrew by Hayyim Tzvi Lerner, St. Petersburg, 1880.

- Discorsi Storico-Religiosi agli Studenti Israeliti. Padua, 1870.

- Introduzione Critica ed Ermenutica al Pentateuco. Padua, 1870.

- Autobiografia (first published by Luzzatto himself in "Mosé," i-vi.). Padua, 1882.

Isaiah Luzzatto published (Padua, 1881), under the respective Hebrew and Italian titles "Reshimat Ma'amarei SHeDaL" and "Catalogo Ragionato degli Scritti Sparsi di S. D. Luzzatto," an index of all the articles which Luzzatto had written in various periodicals.

The "Penine Shedal" ("The Pearls of Samuel David Luzzatto"), published by Luzzatto's sons, is a collection of 89 of the more interesting of Luzzatto's letters. These letters are really scientific treatises, which are divided in this book into different categories as follows: bibliographical (numbers 1-22), containing letters on Ibn Ezra's "Yesod Mora" and "Yesod Mispar"; liturgical-bibliographical and various other subjects (23-31); Biblical-exegetical (32-52), containing among others a commentary on Ecclesiastes and a letter on Samaritan writing; other exegetical letters (53-62); grammatical (63-70); historical (71-77), in which the antiquity of the Book of Job is discussed; philosophical (78-82), including letters on dreams and on the Aristotelian philosophy; theological (83-89), in the last letter of which Luzzatto proves that Ibn Gabirol's ideas were very different from those of Spinoza, and declares that every honest man should rise against the Spinozists.

References

- Compare "Il Vessillo Israelitico," xxv. 374, xxvi. 16

- Preface to his "Ohev Ger"

- "Penine Shadal," p. 417

- "Kerem Ḥemed," iv. 131 et seq.

- Gorgias Press

- Bernfeld, in Sefer ha-Shanah, ii. 278 et seq.;

- idem, in Gedenkbuch zum Hundertsten Geburtstag Luzzattos, Berlin, 1900;

- Educatore Israelita, xiii. 313, 357, 368; xiv. 19;

- Geiger, in Jüd. Zeit. iv. 1-22;

- A. Kahana, in Ha-Shiloaḥ, iii. 58, 337; iv. 58, 153;

- J. Klausner, ib. vii. 117-126, 213-228, 299-305;

- S. D. Luzzatto, Autobiografia, Padua, 1882;

- idem, in Ha-Maggid, ii., Nos. 17-19, 22, 23, 30, 33; iii., Nos. 1, 13, 14, 21, 22, 31-33; vi., Nos. 12, 15, 16, 21-23;

- H. S. Morais, Eminent Israelites of the Nineteenth Century, pp. 211–217, Philadelphia, 1880;

- Senior Sachs, in Ha-Lebanon, ii. 305, 327, 344.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Samuel David Luzzatto. |

- Works by or about Samuel David Luzzatto at Internet Archive

- Literature by and about Samuel David Luzzatto in University Library JCS Frankfurt am Main: Digital Collections Judaica

- Vikkuach al Chakhmat HaKabbalah V'al Kadmut Sefer HaZohar

- A Letter to Almeda: Shadal’s Guide for the Perplexed - Luzzatto's explanation of the principles of Jewish faith, translated to English.