Samsat

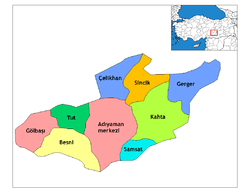

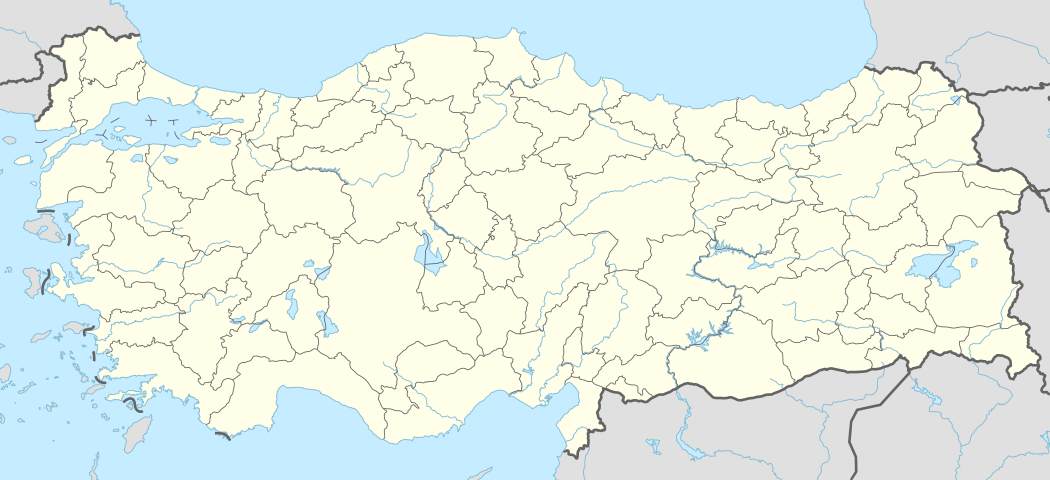

Samsat (Kurdish: Samîsad[1], Armenian: Շամուշատ Shamushat) is a small town and district in the Adıyaman Province of Turkey, situated on the upper Euphrates river. Halil Fırat from the Justice and Development Party (AKP) was elected mayor in the local elections in March 2019.[2] The current Kaymakam is Halid Yıldız.[3]

Samsat | |

|---|---|

Samsat | |

| Coordinates: 37°34′46.4″N 38°28′52.7″E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Adıyaman Province |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Halil Fırat (AKP) |

| • Kaymakam | Halid Yıldız |

| Website | http://www.samsat.gov.tr |

Known as Samosata[4] in antiquity, the city was continuously inhabited for thousands of years. The current site of Samsat is comparatively new, however, being built only since 1989 when the old town of Samosata was flooded during construction of the Atatürk Dam.[5] Indeed, to some extent the re-construction of the town is still ongoing[6] A even more ancient tell nearby dating back to the paleolithic era has survived to the current day.

In 2016 the town had a population of 3789,[7] down from 4720 in 2008 and a peak of 6.917 in 2000. Almost all of the population are Kurds.

Name

The name Semiata or Samsat is known from Sumerian records. The town was a center of the Hittite kingdom in the Iron Age and was called Kummuh in that period.[8][9]

By the Hellenistic Period, the Greeks and Romans knew the city as Samosata (Ancient Greek: Σαμόσατα) or Samosate.[10][11]

The most commonly accepted origin of the name suggests that ancient Samosata was so named in honour of Sames I, an Orontid king of Armenia and Sophene who ruled around 260 BCE.[12][13][14][15] Samosata was also later known as "Antiochia in Commagene" The name of the city passed on to Old Armenian: Շամուշատ Shamushat, and Syriac: ܫܡܝܫܛ šmīšaṭ.

The Islamic conquest brought the Arabisation of this name as Sümeysat İslam and the Ottomans called it Samsat.

History

Antiquity

The region was conquered by Sargon in 708 BC and became a province of Assyria.[9] In 605 BCE, the Babylonians took over. Then, respectively, the Medes, the Persians (533 BC). Alexander the great extended the kingdom of Macedonia in 333 BC from which the town was ceded to the domination of the Seleucids.

Control of the region of Commagene was apparently held by the Orontid dynasty since the 3rd century BCE, who also ruled over Armenia and Sophene. These seem to have held Commagene continuously from the time of Sames I, as the later kings of Commagene of the 2nd century BCE traced their lineage back to them.[16]

The city was the capital of the Orontid Kingdom of Commagene from c. 160 BC until it was surrendered to Rome in 72. Under Antiochus I (69 - 34 BC) the town was a center of caravan routes and a trading center. Located on the upper Euphrates River, it was fortified so as to protect a major crossing point of the river on the east–west trade route. It also served as a station on another route running from Damascus, Palmyra, and Sura up to Armenia and the Euxine Sea. King Antichos III was the last effective ruler,[17] and his death cause a political crisis of succession into which Rome intervened in 72 AD.[18] In the Roman Empire, Samosata was the home of the Legio VI Ferrata and later Legio XVI Flavia Firma, and the terminus of several military roads.

It was at Samosata that Julian II had ships made in his expedition against Shapur II, and it was a natural crossing-place in the struggle between Heraclius and Chosroes in the 7th century.

Samosata was the birthplace of several renowned people from antiquities such as Lucian (c. 120-192) and Paul of Samosata (fl. 260).

Medieval history

The Arabs took the city from the Byzantines. Safwan bin Muattal died and is buried in Samsat. The 13th century was very hard for the town. Rüknettin Süleyman II of the Anatolian Seljuks took the town in 1203, and Samsat was looted in 1237 by the Harzemşah and was invaded by the Mongol Emperor Hülagü Khan in 1240 and later by the Dulkadiroğulları.

It was absorbed into the Ottoman Empire by Yıldırım Beyazıt in 1392 and in 1401 it is destroyed by Timur. In 1516, Yavuz Sultan Selim retook it for the Ottomans. It lost its old importance in the Ottoman administration and became the center of the sanjak.

Modern times

During the republican period, it became smaller and became a center of the parish. In 1960, Samsat was transformed into a district center and connected to the province of Adıyaman.

The city of Samsat was evacuated from the old settlement on 05.03.1988 due to the Atatürk Dam being left under the lake waters and the center was changed and moved to its present location with the law numbered 3433 dated 21.04.1988. The old town of Samsat and all its history were flooded behind the Atatürk Dam in 1989. The new town was built beside the new waterline by the Turkish government to house the displaced residents.

In Christianity

In the Christian martyrology, seven Christian martyrs were crucified in 297 in Samosata for refusing to perform a pagan rite in celebration of the victory of Maximian over the Sassanids: Abibus, Hipparchus, James, Lollian, Paragnus, Philotheus, and Romanus. Saint Daniel the Stylite was born in a village near Samosata; Saint Rabbulas, venerated on 19 February, who lived in the 6th century at Constantinople, was also a native of Samosata. A Notitia Episcopatuum of Antioch in the 6th century mentions Samosata as an autocephalous metropolis (Échos d'Orient, X, 144); at the synod that reinstated Patriarch Photius I of Constantinople (the Photian Council) of 879, the See of Samosata had already been united to that of Amida (Diyarbakır).[19] As in 586 the titular of Amida bears only this title ([20]), it must be concluded that the union took place between the 7th and the 9th centuries. Earlier bishops included Peperius, who attended the Council of Nicaea (325); Saint Eusebius of Samosata, a great opponent of the Arians, killed by an Arian woman (c. 380), honoured on 22 June; Andrew, a vigorous opponent of Cyril of Alexandria and of the Council of Ephesus.[21]

Chabot gives a list of twenty-eight Syrian Miaphysite bishops.[22] The Syrian bishopric probably lapsed in the 12th century.[23] Samosata is included in the Catholic Church's list of titular sees, but no further titular bishops have been appointed for that eastern see since the Second Vatican Council.

Archaeology

Samsat Höyük is a tell located just north of the Samsat district of Adıyaman. Archaeological research on the hill of Şehremuz in Samsat has uncovered relics from the 7000 BC Paleolithic era; the 5000 BC Neolithic, 3000 BC Chalcolithic and 3000 to 1200 BC Bronze Ages. The ancient city of Ḫaḫḫum (Hittite: Ḫaḫḫa) was located nearby; it is recorded as a source of gold for ancient Sumeria.

The first excavations were conducted in 1964 and 1967 under the direction of T. Goell. In fact, the settlement was known and famous before these excavations. Then, in 1977, under the Lower Euphrates Project, which was aimed at identifying and saving the archaeological settlements that will remain within the water collection area of Karakaya and Atatürk Dams. Surface surveys were conducted under the direction of Mehmet Özdoğan. In these studies, it was concluded that the settlement was permanently inhabited from the Halaf Period to the Ottoman Period. The following year, the excavations started in 1978, except for 1980, until 1987, Ankara University, Faculty of Language and History-Geography Professor. Dr. It was conducted by the team led by Nimet Özgüç. These excavations were carried out on a very wide area, including the lower city and surrounding walls.

Coins belonging to the 12th - 13th centuries AD were identified during the excavations in the layers dating to the late phases of the Middle Ages. Of these Seljuk sultans I. Gıyaseddin Keyhusrev (1192-1195), Ala al-Din Keykubbad, (1219-1236), II. Gıyaseddin Keyhusrev (1236-1246), IV. Rükn el-Din The coins of Kılıç Arslan (1257-1264), as well as the coins of Saladin (1170-1193) printed in Harran, were uncovered.[24]

The collection of glassware with cups, glasses and bowls is very rich. Other finds include oil lamps, ivory comb, fragrance bottle,[25], terracotta lamps, bone spoons, leaf-shaped marble sconces and coins.[26]

The walls of the Seljuk Period, built on a solid Byzantine fortress, were preserved intact. The inscription on the limestone of this fortification was studied by a master calligrapher. The landfill belonged to Diyarbekr Şah Karaaslan.[27]

The center of the palace, which is thought to be the central courtyard, is 14,65 X 20,55 meters and it has a mosaic corner.[28]

The skeletons of five people thrown into a 1.8 meter diameter well of the Islamic Period were found. At the bottom of the skeleton at the bottom of the skeleton, there are five gold coins and silver coins from the Abbasid Period. One of the gold coins belongs to Harunürreşid (766 - 709) and the other to Mutevekkil (822 - 861).[29]

Today the settlement is 700 meters inside the Euphrates but before inundation it was 37-40 meters above the plain level and has an area of 500 x 350 meters. The most steep slope is the eastern slope and the lowest slope is the southwest facing slope. The mound consists of a terrace and a sub-city.[30] Samsat Höyük as an archaeological site is considered to have been destroyed due to the importance it carries in the dam lake.

The old town of Samosta below the tell was not excavated [31]

Geography

The new Samsat district is a peninsula surrounded on the three sides by the Atatürk Dam Lake. The distance from the sea to the city center is 47km. The district is a plain that descends to the south.

In the hot summers and dry winters, while the Mediterranean climate is warm and rainy, it is similar to the South East Anatolian climate due to the low relative humidity. However, due to the Atatürk Dam Lake in recent years, the humidity has increased relatively.

References

- adem Avcıkıran (2009). Kürtçe Anamnez Anamneza bi Kurmancî (PDF) (in Turkish and Kurdish). p. 56. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Adıyaman Samsat Seçim Sonuçları - 31 Mart 2019 Yerel Seçimleri". www.sabah.com.tr. Retrieved 2019-12-18.

- "T.C. Samsat Kaymakamlığı". www.samsat.gov.tr. Retrieved 2019-12-18.

- Old Armenian: Շամուշատ, Shamushat, Ancient Greek: Σαμόσατα Samósata, Syriac: ܫܡܝܫܛ šmīšaṭ

- Samsat, Gezilecek Yerler.

- Samsat’ta kalıcı konutların temelleri atılıyor.

- "2016 genel nüfus sayımı verileri" (html) (Doğrudan bir kaynak olmayıp ilgili veriye ulaşmak için sorgulama yapılmalıdır). Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Erişim tarihi: 7 Mart 2017.

- See Malpınarı Rock Inscription

- Michael Blömer / Religious Life of Commagene in the Late Hellenistic and Early Roman Period pp.95-129/The Letter of Mara bar Sarapion in Context. Proceedings of the Symposium Held at Utrecht University, 10–12 December 2009 /BRILL 2012

In doing so, Samosata, the Commagenian capital and hometown of Mara bar Sarapion, would suit best as the prime object of investigation. The place was one of the most important sites along the Upper Euphrates. It offered an easy crossing of the river and was occupied since Chalcolithic times. It is named Kummuḫ in Iron Age sources and was the centre of an eponymous independent Syro-Hittite kingdom from the 12th to the 8th century BCE. The Assyrian king Sargon II conquered Kummuḫ in 708 BCE, but it remained an important provincial town during late Iron Age. In Hellenistic times it was capital of the kingdom of Commagene. The city was renamed Samosata by a predecessor of the Commagenian royal family, the Armenian king Samos I, in the 3rd century BCE. After the Roman occupation in CE 72, Samosata prospered as a major commercial, cultural and military centre of the Roman province of Syria.

- The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites, SAMOSATA (Sainsat) SW Anatolia.

- Prof. Dr. Gönül Öney, 1978 – 79 ve 1981 Yılı Samsat Kazılarında Bulunan İslam Devri Buluntularıyla İlgili İlk Haber Sh.: 71

- Toumanoff, Cyril Studies in Christian Caucasian History (1963), p. 280 and 292, Georgetown University Press

- Nemrud Dağı Text, Theresa Goell, Donald Hugo Sanders, ed. Eisenbrauns, 1996, p. 367 "Puchstein's epigraphic interpretation was not unambiguous; the name of the father could be read or restored to Samos (Sames) or Arsames. Puchstein had decided to read Samos; Honigmann (1963: 981) decided likewise to read Samos; Reinach and" ... "Samos was the "founder" of Samosata in the same way that his son Arsames was "founder" of Arsameia ", p.368 "Chronologically, this king Samos belongs to the first half of the third century B.C.E."

- M. J. Versluys/ Visual Style and Constructing Identity in the Hellenistic World: Nemrud Dag and Commagene under Antiochos I/Cambridge University Press, 2017 г.—pp.48 (312) ISBN 1107141974, 9781107141971

We know nothing about the status of Commagene under Seleucid rule. The Armenian king Samos I is believed to have founded Samosata, later the capital of Commagene, in the middle of the third century BC. The second century BC saw the rise of the two powers that would play an important role in Commagene's future during the next centuries: Rome and Parthia. Their growing prominence, combined with the failing of the central Seleucid power, resulted in the rise of several small monarchies, of which Commagene was one. Other independent kingdoms that came into being around this time include Pergamon, Pontos, Baktria, Parthia, Armenia, Iudea and Nabatea. Diodorus tells us that a Seleucid epistates named Ptolemy rose to power in Commagene in 163 BC. Most scholars assume that Ptolemy was the first Commagenean king and that he descended from the Armenian Orontids. We know virtually nothing about the following decades. Samos II took power around 130 BC, as is concluded from some coins that have been preserved, showing a portrait with the inscription “king Samos.”

- Not to be confused with a later Sames/Samos (Sames II), who ruled Commagene in the second century BCE

- Brijder, Herman (2014). Nemrud Dagi : recent archaeological research and conservation activities in the tomb sanctuary on Mount Nemrud. ISBN 9781614519058.

- Chahin, Mark (2001). The Kingdom of Armenia. Routledge. pp. 190–191. ISBN 0-7007-1452-9.

- Tacitus, The Annals 2.42.

- Mansi, Conciliorum collectio, XVII-XVIII, 445.

- Le Quien, Oriens christianus, II, 994.

- Le Quien, Oriens christianus, II, 933-6.

- Revue de l'Orient chrétien, VI, 203.

- Fiey, J. M. (1993), Pour un Oriens Christianus novus; répertoire des diocèses Syriaques orientaux et occidentaux, Beirut, p. 263, ISBN 3-515-05718-8

- Nimet Özgüç, 1985 Yılında Yapılmış Olan Samsat Kazılarının Sonuçları' – 8. Kazı Sonuçları Toplantısı (1986) Sh.: 297

- Nimet Özgüç, 8. Kazı Sonuçları Toplantısı, p298

- Nimet Özgüç, 7. Kazı Sonuçları Toplantısı, p 227

- Nimet Özgüç, Samsat Kazıları 1982' – 5. Kazı Sonuçları Toplantısı (1983) p111.

- Nimet Özgüç, Samsat 1984 Yılı Kazıları, 7. Kazı Sonuçları Toplantısı (1985) p224.

- Nimet Özgüç, 7. Kazı Sonuçları Toplantısı (1985) Sh.: 226

- TAY – Yerleşme Ayrıntıları.

- Adıyaman, Samsat.