Dried and salted cod

Dried and salted cod, sometimes referred to as salt cod or saltfish, is cod which has been preserved by drying after salting. Cod which has been dried without the addition of salt is stockfish. Salt cod was long a major export of the North Atlantic region, and has become an ingredient of many cuisines around the Atlantic and in the Mediterranean. With the sharp decline in the world stocks of cod, other salted and dried white fish are sometimes marketed as "salt cod", and the term has become to some extent a generic name.

Dried and salted cod has been produced for over 500 years in Newfoundland, Iceland, and the Faroe Islands, and most particularly in Norway where it is called klippfisk, literally "cliff-fish". Traditionally it was dried outdoors by the wind and sun, often on cliffs and other bare rock-faces. Today klippfisk is usually dried indoors with the aid of electric heaters.

History

The production of salt cod dates back at least 1000 years, to the time of the Vikings. When explorer Jacques Cartier discovered the mouth of the St. Lawrence River in what is now Canada and claimed it for France, he noted the presence of a thousand Basque boats fishing for cod.

Salt cod formed a vital item of international commerce between the New World and the Old, and formed one leg of the so-called triangular trade. Thus it spread around the Atlantic and became a traditional ingredient not only in Northern European cuisine, but also in Mediterranean, West African, Caribbean, and Brazilian cuisines.

The drying of food is the world's oldest known preservation method, and dried fish has a storage life of several years. Traditionally, salt cod was dried only by the wind and the sun, hanging on wooden scaffolding or lying on clean cliffs or rocks near the seaside.

Drying preserves many nutrients, and the process of salting and drying codfish is said to make it tastier.[1] Salting became economically feasible during the 17th century, when cheap salt from southern Europe became available to the maritime nations of northern Europe. The method was cheap and the work could be done by the fisherman or his family. The resulting product was easily transported to market, and salt cod became a staple item in the diet of the populations of Catholic countries on 'meatless' Fridays and during Lent.

Names

In Middle English dried and salted cod was called haberdine.[2][3] Dried cod and the dishes made from it are known by many names around the world, many of them derived from the root bacal-, itself of unknown origin.[3] Explorer John Cabot reported that it was the name used by the inhabitants of Newfoundland.[4] Some of these are: bacalhau (salgado) (Portuguese), bacalao salado (Spanish), bakailao (Basque), bacallà salat i assecat or bacallà salat (Catalan), μπακαλιάρος, bakaliáros (Greek), Klippfisch (German), cabillaud (French), baccalà (Italian), bakalar (Croatian), bakkeljauw (Dutch), bakaljaw (Maltese), makayabu (Central and East Africa), and kapakala (Finnish). Other names include ráktoguolli/goikeguolli (Sami), klipfisk/klippfisk/clipfish (Scandinavian, Russian), stokvis/klipvis (Dutch), saltfiskur (Icelandic), morue (French), bartolitius (Canadian) and saltfish (Anglophone Caribbean), .

Process

The fish is beheaded and eviscerated, often on board the boat or ship. (This is feasible with whitefish, whereas it would not be with oily fish.) It is then salted and dried ashore. Traditionally the fish was sun-dried on rocks or wooden frames, but modern commercial production is mainly dried indoors with electrical heating. It is sold whole or in portions, with or without bones.

Species of fish

Prior to the collapse of the Grand Banks (and other) stocks due to overfishing, salt cod was derived exclusively from Atlantic cod. Since then products sold as salt cod may be derived from other whitefish, such as pollock, haddock, blue whiting, ling and tusk. In South America, catfish of the genera Pseudoplatystoma are used to produce a salted, dried and frozen product typically sold around Lent.

Quality grades

In Norway, there used to be five different grades of salt cod. The best grade was called superior extra. Then came (in descending order) superior, imperial, universal and popular. These appellations are no longer extensively used, although some producers still make the superior products.

The best klippfisk, the superior extra, is made only from line-caught cod. The fish is always of the skrei, the cod that once a year is caught during spawning. The fish is bled while alive, before the head is cut off. It is then cleaned, filleted and salted. Fishers and connoisseurs alike place a high importance in the fact that the fish is line-caught, because if caught in a net, the fish may be dead before caught, which may result in bruising of the fillets. For the same reason it is believed to be important that the klippfisk be bled while still alive. Superior klippfisk is salted fresh, whereas the cheaper grades of klippfisk might be frozen first.

Lower grades are salted by injecting a salt-water solution into the fish, while superior grades are salted with dry salt. The superior extra is dried twice, much like Parma ham. Between the two drying sessions, the fish rests and the flavour matures.

Culinary uses

Before it can be eaten, salt cod must be rehydrated and desalinated by soaking in cold water for one to three days, changing the water two to three times a day.

In Europe, the fish is prepared for the table in a wide variety of ways;[5] most commonly with potatoes and onions in a casserole, as croquettes, or as battered, deep-fried pieces. In France, brandade de morue is a popular baked gratin dish of potatoes mashed with rehydrated salted cod, seasoned with garlic and olive oil. Some Southern France recipes skip the potatoes altogether and blend the salted cod with seasonings into a paste.[6] There is a particularly wide variety of salt cod dishes in Portuguese cuisine. In Greece, fried cod is often served with skordalia.

Salt cod is part of many European celebrations of the Christmas Vigil, in particular the southern Italian Feast of the Seven Fishes.

In several islands of the West Indies, it forms the basis of the common dish saltfish. In Jamaica, the national dish is ackee and saltfish. In Bermuda, it is served with potatoes, avocado, banana and boiled egg in the traditional codfish and potato breakfast. In some regions of Mexico, it is fried with egg batter, then simmered in red sauce and served for Christmas dinner.

In Liverpool, England, prior to the post-war slum clearances, especially around the docks,[7] salt fish was a popular traditional Sunday morning breakfast.[8]

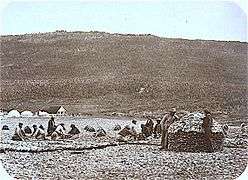

Cod preparation, French fishing station in Cape Rouge, Newfoundland, ca. 1857-1859.

Cod preparation, French fishing station in Cape Rouge, Newfoundland, ca. 1857-1859. Drying of salt cod in 19th century Iceland

Drying of salt cod in 19th century Iceland- Strips of dried and salted Russian cod

Morue for sale at a Nice market

Morue for sale at a Nice market Bacalao for sale at a market in Valencia

Bacalao for sale at a market in Valencia

See also

- Bacalhau

- Fish processing

- List of dried foods – Wikipedia list article

- Stockfish – Unsalted fish preserved by drying in cold air and wind

Notes

- Ruhlman, Michael; Polcyn, Brian. Charcuterie: The Craft of Salting, Smoking, and Curing. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Tanner J. R. (2013) Samuel Pepys and the Royal Navy page 61, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107626430

- Sutton, David C. (2011) "The Stories of Bacalao: Myth, legend and History" In: Helen Saberi (Ed) Cured, Smoked, and Fermented, Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cooking, page 312. ISBN 9781903018859

- OED, s.v. bacalao

- Sanjuán, 2009

- "Nîmes brandade". Everything2. 8 June 2004. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- "New book remembers Liverpool's slum clearance". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- Merseypride. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dried and salted cod. |

- Davidson, Alan (1979). North Atlantic Seafood. ISBN 0-670-51524-8.

- Kurlansky, Mark (1997). Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World. New York: Walker. ISBN 0-8027-1326-2.

- Sanjuán, Gloria (2009). La Cocina del Bacalao. Madrid: Libro Hobby. ISBN 978-84-9736-242-9.

- SILVA, A. J. M. (2015), The fable of the cod and the promised sea. About Portuguese traditions of bacalhau, in BARATA, F. T- and ROCHA, J. M. (eds.), Heritages and Memories from the Sea, Proceedings of the 1st International Conference of the UNESCO Chair in Intangible Heritage and Traditional Know-How: Linking Heritage, 14–16 January 2015. University of Evora, Évora, pp. 130–143.