Saint Quentin

Saint Quentin (Latin: Quintinus; died c. 287 AD) also known as Quentin of Amiens, was an early Christian saint. No real details are known of his life.

Saint Quentin | |

|---|---|

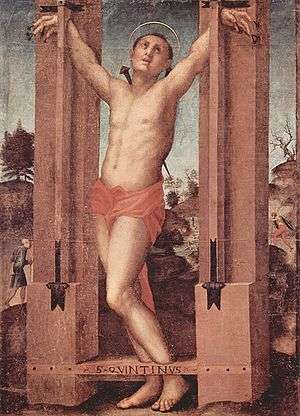

The martyrdom of Saint Quentin, Jacopo Pontormo | |

| Martyr | |

| Born | unknown |

| Died | c. 287 Saint-Quentin, France |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | Saint-Quentin, France |

| Feast | October 31 |

| Attributes | depicted as a young man with two spits; as a deacon; with a broken wheel; with a chair to which he is transfixed; with a sword; or beheaded, a dove flying from his severed head[1] |

| Patronage | bombardiers, chaplains, locksmiths, porters, tailors, and surgeons. Invoked against coughs, sneezes, and dropsy |

Hagiography

Martyrdom

The legend of his life has him as a Roman citizen who was martyred in Gaul. He is said to have been the son of a man named Zeno, who had senatorial rank. Filled with apostolic zeal, Quentin traveled to Gaul as a missionary with Saint Lucian, who was later martyred at Beauvais, and others (the martyrs Victoricus and Fuscian are said to have been Quentin's followers). Quentin settled at Amiens and performed many miracles there.[2]

Because of his preaching, he was imprisoned by the prefect Rictiovarus, who had traveled to Amiens from Trier. Quentin was manacled, tortured repeatedly, but refused to abjure his faith.[2] The prefect left Amiens to go to Reims, the capital of Gallia Belgica, where he wanted Quentin judged. But, on the way, in a town named Augusta Veromanduorum (now Saint-Quentin, Aisne), Quentin miraculously escaped and again started his preaching. Rictiovarus decided to interrupt his journey and pass sentence: Quentin was tortured again, then beheaded and thrown secretly into the marshes around the Somme, by Roman soldiers.

First inventio

Five years later, a blind woman named Eusebia, born of a senatorial family, came from Rome (following a divine order) and miraculously discovered the body.[2] The intact remains of Quentin came into view, arising from the water and emanating an odor of sanctity. She buried his body at the top of a mountain near Augusta Veromanduorum (because the chariot on which the saint's body lay could not go further). She built a small chapel to protect the tomb and recovered her sight.

Second inventio

The life of bishop Saint Eligius (mainly written in the seventh century), says that the exact place of the tomb was forgotten and that the bishop, after several days of digging in the church, miraculously found it. When he found the tomb, the sky night was lit and the odor of sanctity was evident. This was said to be in 641. Recent archaeological research shows this to be false, because the location of the tomb had been marked by a sort of wooden monument since the middle of the fourth or the beginning of the fifth century.

Eligius distributed the nails with which Quentin's body had been pierced, as well as some saint's teeth and hair. As he was a skillful goldsmith, he placed the relics in a shrine he had fashioned himself. He also rebuilt the church (now the Saint-Quentin basilica).

Cult

The cult of Saint Quentin was important during the Middle Ages, especially in Northern France—as evidenced by the considerable number of place names derived from the saint's (see Saint-Quentin (disambiguation)). The tomb was an important place of pilgrimage, highly favoured by Carolingians (the church was one of the richest in Picardy).

References

- Stracke, Richard (2015-10-20). "Saint Quentin: The Iconography".

- de Voragine, Jacobus (2003-09-03). "The Golden Legend" (PDF).

External links

- Saint Quentin at Saints.SQPN.com

- Catholic Online: Saint Quentin

- Saint of the Day, October 31: Quentin of Amiens at SaintPatrickDC.org

![]()