International System of Units

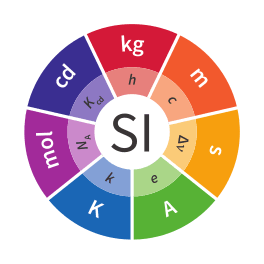

The International System of Units (SI, abbreviated from the French Système international (d'unités)) is the modern form of the metric system. It is the only system of measurement with an official status in nearly every country in the world. It comprises a coherent system of units of measurement starting with seven base units, which are the second (the unit of time with the symbol s), metre (length, m), kilogram (mass, kg), ampere (electric current, A), kelvin (thermodynamic temperature, K), mole (amount of substance, mol), and candela (luminous intensity, cd). The system allows for an unlimited number of additional units, called derived units, which can always be represented as products of powers of the base units.[Note 1] Twenty-two derived units have been provided with special names and symbols.[Note 2] The seven base units and the 22 derived units with special names and symbols may be used in combination to express other derived units,[Note 3] which are adopted to facilitate measurement of diverse quantities. The SI system also provides twenty prefixes to the unit names and unit symbols that may be used when specifying power-of-ten (i.e. decimal) multiples and sub-multiples of SI units. The SI is intended to be an evolving system; units and prefixes are created and unit definitions are modified through international agreement as the technology of measurement progresses and the precision of measurements improves.

| SI Base Units | ||

| Symbol | Name | Quantity |

| s | second | time |

| m | metre | length |

| kg | kilogram | mass |

| A | ampere | electric current |

| K | kelvin | thermodynamic temperature |

| mol | mole | amount of substance |

| cd | candela | luminous intensity |

| SI Defining Constants | ||

| Symbol | Name | Exact Value |

| hyperfine transition frequency of Cs | 9192631770 Hz | |

| c | speed of light | 299792458 m/s |

| h | Planck constant | 6.62607015×10−34 J⋅s |

| e | elementary charge | 1.602176634×10−19 C |

| k | Boltzmann constant | 1.380649×10−23 J/K |

| NA | Avogadro constant | 6.02214076×1023 mol−1 |

| Kcd | luminous efficacy of 540 THz radiation | 683 lm/W |

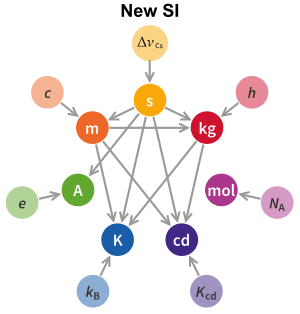

Since 2019, the magnitudes of all SI units have been defined by declaring exact numerical values for seven defining constants when expressed in terms of their SI units. These defining constants are the speed of light in vacuum, c, the hyperfine transition frequency of caesium ΔνCs, the Planck constant h, the elementary charge e, the Boltzmann constant k, the Avogadro constant NA, and the luminous efficacy Kcd. The nature of the defining constants ranges from fundamental constants of nature such as c to the purely technical constant Kcd. Prior to 2019, h, e, k, and NA were not defined a priori but were rather very precisely measured quantities. In 2019, their values were fixed by definition to their best estimates at the time, ensuring continuity with previous definitions of the base units. One consequence of the redefinition of the SI is that the distinction between the base units and derived units is in principle not needed, since any unit can be constructed directly from the seven defining constants.[2]:129

The current way of defining the SI system is a result of a decades-long move towards increasingly abstract and idealised formulation in which the realisations of the units are separated conceptually from the definitions. A consequence is that as science and technologies develop, new and superior realisations may be introduced without the need to redefine the unit. One problem with artefacts is that they can be lost, damaged, or changed; another is that they introduce uncertainties that cannot be reduced by advancements in science and technology. The last artefact used by the SI was the International Prototype of the Kilogram, a cylinder of platinum-iridium.

The original motivation for the development of the SI was the diversity of units that had sprung up within the centimetre–gram–second (CGS) systems (specifically the inconsistency between the systems of electrostatic units and electromagnetic units) and the lack of coordination between the various disciplines that used them. The General Conference on Weights and Measures (French: Conférence générale des poids et mesures – CGPM), which was established by the Metre Convention of 1875, brought together many international organisations to establish the definitions and standards of a new system and to standardise the rules for writing and presenting measurements. The system was published in 1960 as a result of an initiative that began in 1948. It is based on the metre–kilogram–second system of units (MKS) rather than any variant of the CGS.

Introduction

The International System of Units, the SI,[2]:123 is a decimal[Note 4] and metric[Note 5] system of units established in 1960 and periodically updated since then. The SI has an official status in most countries,[Note 6] including the United States[Note 8] and the United Kingdom, with these two countries being amongst a handful of nations that, to various degrees, continue to resist widespread internal adoption of the SI system. As a consequence, the SI system “has been used around the world as the preferred system of units, the basic language for science, technology, industry and trade.”[2]:123

The only other types of measurement system that still have widespread use across the world are the Imperial and US customary measurement systems, and they are legally defined in terms of the SI system.[Note 9] There are other, less widespread systems of measurement that are occasionally used in particular regions of the world. In addition, there are many individual non-SI units that don't belong to any comprehensive system of units, but that are nevertheless still regularly used in particular fields and regions. Both of these categories of unit are also typically defined legally in terms of SI units.[Note 10]

Controlling body

The SI was established and is maintained by the General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM[Note 11]).[4] In practice, the CGPM follows the recommendations of the Consultative Committee for Units (CCU), which is the actual body conducting technical deliberations concerning new scientific and technological developments related to the definition of units and the SI. The CCU reports to the International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM[Note 12]), which, in turn, reports to the CGPM. See below for more details.

All the decisions and recommendations concerning units are collected in a brochure called The International System of Units (SI)[Note 13], which is published by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM[Note 14]) and periodically updated.

Overview of the units

SI base units

The SI selects seven units to serve as base units, corresponding to seven base physical quantities.[Note 15] They are the second, with the symbol s, which is the SI unit of the physical quantity of time; the metre, symbol m, the SI unit of length; kilogram (kg, the unit of mass); ampere (A, electric current); kelvin (K, thermodynamic temperature), mole (mol, amount of substance); and candela (cd, luminous intensity).[2] Note that 'the choice of the base units was never unique, but grew historically and became familiar to users of the SI'.[2]:126 All units in the SI can be expressed in terms of the base units, and the base units serve as a preferred set for expressing or analysing the relationships between units.

SI derived units

The system allows for an unlimited number of additional units, called derived units, which can always be represented as products of powers of the base units, possibly with a nontrivial numeric multiplier. When that multiplier is one, the unit is called a coherent derived unit.[Note 16] The base and coherent derived units of the SI together form a coherent system of units called the set of coherent SI units.[Note 17] Twenty-two coherent derived units have been provided with special names and symbols.[Note 18] The seven base units and the 22 derived units with special names and symbols may be used in combination to express other derived units,[Note 19] which are adopted to facilitate measurement of diverse quantities.

SI metric prefixes and the decimal nature of the SI system

Like all metric systems, the SI uses metric prefixes to systematically construct, for one and the same physical quantity, a whole set of units of widely different sizes that are decimal multiples of each other.

For example, while the coherent unit of length is the metre,[Note 20] the SI provides a full range of smaller and larger units of length, any of which may be more convenient for any given application – for example, driving distances are normally given in kilometres (symbol km) rather than in metres. Here the metric prefix ‘kilo-’ (symbol ‘k’) stands for a factor of 1000; thus, 1 km = 1000 m.[Note 21]

The current version of the SI provides twenty metric prefixes that signify decimal powers ranging from 10−24 to 1024.[2]:143–4 Apart from the prefixes for 1/100, 1/10, 10, and 100, all the other ones are powers of 1000.

In general, given any coherent unit with a separate name and symbol,[Note 22] one forms a new unit by simply adding an appropriate metric prefix to the name of the coherent unit (and a corresponding prefix symbol to the unit's symbol). Since the metric prefix signifies a particular power of ten, the new unit is always a power-of-ten multiple or sub-multiple of the coherent unit. Thus, the conversion between units within the SI is always through a power of ten; this is why the SI system (and metric systems more generally) are called decimal systems of measurement units.[6][Note 23]

The grouping formed by a prefix symbol attached to a unit symbol (e.g. 'km', 'cm') constitutes a new inseparable unit symbol. This new symbol can be raised to a positive or negative power and can be combined with other unit symbols to form compound unit symbols.[2]:143 For example, g/cm3 is an SI unit of density, where cm3 is to be interpreted as (cm)3.

Coherent and non-coherent SI units

When prefixes are used with the coherent SI units, the resulting units are no longer coherent, because the prefix introduces a numerical factor other than one.[2]:137 The one exception is the kilogram, the only coherent SI unit whose name and symbol, for historical reasons, include a prefix.[Note 24]

The complete set of SI units consists of both the coherent set and the multiples and sub-multiples of coherent units formed by using the SI prefixes.[2]:138 For example, the metre, kilometre, centimetre, nanometre, etc. are all SI units of length, though only the metre is a coherent SI unit. A similar statement holds for derived units: for example, kg/m3, g/dm3, g/cm3, Pg/km3, etc. are all SI units of density, but of these, only kg/m3 is a coherent SI unit.

Moreover, the metre is the only coherent SI unit of length. Every physical quantity has exactly one coherent SI unit, although this unit may be expressible in different forms by using some of the special names and symbols.[2]:140 For example, the coherent SI unit of linear momentum may be written as either kg⋅m/s or as N⋅s, and both forms are in use (e.g. compare respectively here[7]:205 and here[8]:135).

On the other hand, several different quantities may share same coherent SI unit. For example, the joule per kelvin is the coherent SI unit for two distinct quantities: heat capacity and entropy. Furthermore, the same coherent SI unit may be a base unit in one context, but a coherent derived unit in another. For example, the ampere is the coherent SI unit for both electric current and magnetomotive force, but it is a base unit in the former case and a derived unit in the latter.[2]:140[Note 26]

Non-SI units accepted for use with SI

There is a special group of units that are called ‘non-SI units that are accepted for use with the SI’ (see below for a complete list).[2]:145 Most of these, in order to be converted to the corresponding SI unit, require conversion factors that are not powers of ten. Some common examples of such units are the customary units of time, namely the minute (conversion factor of 60, since 1 min = 60 s), the hour (3600 s), and the day (86400 s); the degree (for measuring plane angles, 1° = π/180 rad); and the electronvolt (a unit of energy, 1 eV = 1.602176634×10−19 J).

New units

The SI is intended to be an evolving system; units[Note 27] and prefixes are created and unit definitions are modified through international agreement as the technology of measurement progresses and the precision of measurements improves.

Defining magnitudes of units

Since 2019, the magnitudes of all SI units have been defined in an abstract way, which is conceptually separated from any practical realisation of them.[2]:126[Note 28] Namely, the SI units are defined by declaring that seven defining constants[2]:125–9 have certain exact numerical values when expressed in terms of their SI units. Probably the most widely known of these constants is the speed of light in vacuum, c, which in the SI by definition has the exact value of c = 299792458 m/s. The other six constants are , the hyperfine transition frequency of caesium; h, the Planck constant; e, the elementary charge; k, the Boltzmann constant; NA, the Avogadro constant; and Kcd, the luminous efficacy of monochromatic radiation of frequency 540×1012 Hz.[Note 29] The nature of the defining constants ranges from fundamental constants of nature such as c to the purely technical constant Kcd.[2]:128–9. Prior to 2019, h, e, k, and NA were not defined a priori but were rather very precisely measured quantities. In 2019, their values were fixed by definition to their best estimates at the time, ensuring continuity with previous definitions of the base units.

As far as realisations, what are believed to be the current best practical realisations of units are described in the so-called ‘mises en pratique’,[Note 30] which are also published by the BIPM.[11] The abstract nature of the definitions of units is what makes it possible to improve and change the mises en pratique as science and technology develop without having to change the actual definitions themselves.[Note 33]

In a sense, this way of defining the SI units is no more abstract than the way derived units are traditionally defined in terms of the base units. Let us consider a particular derived unit, say the joule, the unit of energy. Its definition in terms of the base units is kg⋅m2/s2. Even if the practical realisations of the metre, kilogram, and second are available, we do not thereby immediately have a practical realisation of the joule; such a realisation will require some sort of reference to the underlying physical definition of work or energy—some actual physical procedure (a mise en pratique, if you will) for realising the energy in the amount of one joule such that it can be compared to other instances of energy (such as the energy content of gasoline put into a car or of electricity delivered to a household).

The situation with the defining constants and all of the SI units is analogous. In fact, purely mathematically speaking, the SI units are defined as if we declared that it is the defining constant's units that are now the base units, with all other SI units being derived units. To make this clearer, first note that each defining constant can be taken as determining the magnitude of that defining constant's unit of measurement;[2]:128 for example, the definition of c defines the unit m/s as 1 m/s = c/299792458 (‘the speed of one metre per second is equal to one 299792458th of the speed of light’). In this way, the defining constants directly define the following seven units: the hertz (Hz), a unit of the physical quantity of frequency (note that problems can arise when dealing with frequency or the Planck constant because the units of angular measure (cycle or radian) are omitted in SI.[12][13][14][15][16]); the metre per second (m/s), a unit of speed; joule-second (J⋅s), a unit of action; coulomb (C), a unit of electric charge; joule per kelvin (J/K), a unit of both entropy and heat capacity; the inverse mole (mol−1), a unit of a conversion constant between the amount of substance and the number of elementary entities (atoms, molecules, etc.); and lumen per watt (lm/W), a unit of a conversion constant between the physical power carried by electromagnetic radiation and the intrinsic ability of that same radiation to produce visual perception of brightness in humans. Further, one can show, using dimensional analysis, that every coherent SI unit (whether base or derived) can be written as a unique product of powers of the units of the SI defining constants (in complete analogy to the fact that every coherent derived SI unit can be written as a unique product of powers of the base SI units). For example, the kilogram can be written as kg = (Hz)(J⋅s)/(m/s)2.[Note 34] Thus, the kilogram is defined in terms of the three defining constants ΔνCs, c, and h because, on the one hand, these three defining constants respectively define the units Hz, m/s, and J⋅s,[Note 35] while, on the other hand, the kilogram can be written in terms of these three units, namely, kg = (Hz)(J⋅s)/(m/s)2.[Note 36] True, the question of how to actually realise the kilogram in practice would, at this point, still be open, but that is not really different from the fact that the question of how to actually realise the joule in practice is still in principle open even once one has achieved the practical realisations of the metre, kilogram, and second.

One consequence of the redefinition of the SI is that the distinction between the base units and derived units is in principle not needed, since any unit can be constructed directly from the seven defining constants. Nevertheless, the distinction is retained because 'it is useful and historically well established', and also because the ISO/IEC 80000 series of standards[Note 37] specifies base and derived quantities that necessarily have the corresponding SI units.[2]:129

Specifying fundamental constants vs. other methods of definition

The current way of defining the SI system is the result of a decades-long move towards increasingly abstract and idealised formulation in which the realisations of the units are separated conceptually from the definitions.[2]:126

The great advantage of doing it this way is that as science and technologies develop, new and superior realisations may be introduced without the need to redefine the units.[Note 31] Units can now be realised with ‘an accuracy that is ultimately limited only by the quantum structure of nature and our technical abilities but not by the definitions themselves.[Note 32] Any valid equation of physics relating the defining constants to a unit can be used to realise the unit, thus creating opportunities for innovation… with increasing accuracy as technology proceeds.’[2]:122 In practice, the CIPM Consultative Committees provide so-called "mises en pratique" (practical techniques),[11] which are the descriptions of what are currently believed to be best experimental realisations of the units.[19]

This system lacks the conceptual simplicity of using artefacts (referred to as prototypes) as realisations of units to define those units: with prototypes, the definition and the realisation are one and the same.[Note 38] However, using artefacts has two major disadvantages that, as soon as it is technologically and scientifically feasible, result in abandoning them as means for defining units.[Note 42] One major disadvantage is that artefacts can be lost, damaged,[Note 44]

We shall in the first place describe the state of the Standards recovered from the ruins of the House of Commons, as ascertained in our inspection of them made on 1st June, 1838, at the Journal Office, where they are preserved under the care of Mr. James Gudge, Principal Clerk of the Journal Office. The following list, taken by ourselves from inspection, was compared with a list produced by Mr. Gudge, and stated by him to have been made by Mr. Charles Rowland, one of the Clerks of the Journal Office, immediately after the fire, and was found to agree with it. Mr. Gudge stated that no other Standards of Length or Weight were in his custody.

No. 1. A brass bar marked “Standard [G. II. crown emblem] Yard, 1758,” which on examination was found to have its right hand stud perfect, with the point and line visible, but with its left hand stud completely melted out, a hole only remaining. The bar was somewhat bent, and discoloured in every part.

No. 2. A brass bar with a projecting cock at each end, forming a bed for the trial of yard-measures; discoloured.

No. 3. A brass bar marked “Standard [G. II. crown emblem] Yard, 1760,” from which the left hand stud was completely melted out, and which in other respects was in the same condition as No. 1.

No. 4. A yard-bed similar to No. 2; discoloured.

No. 5. A weight of the form [drawing of a weight] marked [2 lb. T. 1758], apparently of brass or copper; much discoloured.

No. 6. A weight marked in the same manner for 4 lbs., in the same state.

No. 7. A weight similar to No. 6, with a hollow space at its base, which appeared at first sight to have been originally filled with some soft metal that had been now melted out, but which on a rough trial was found to have nearly the same weight as No. 6.

No. 8. A similar weight of 8 lbs., similarly marked (with the alteration of 8 lbs. for 4 lbs.), and in the same state.

No. 9. Another exactly like No. 8.

Nos. 10 and 11. Two weights of 16 lbs., similarly marked.

Nos. 12 and 13. Two weights of 32 lbs., similarly marked.

No. 14. A weight with a triangular ring-handle, marked "S.F. 1759 17 lbs. 8 dwts. Troy", apparently intended to represent the stone of 14 lbs. avoirdupois, allowing 7008 troy grains to each avoirdupois pound.

It appears from this list that the bar adopted in the Act 5th Geo. IV., cap. 74, sect. 1, for the legal standard of one yard, (No. 3 of the preceding list), is so far injured, that it is impossible to ascertain from it, with the most moderate accuracy, the statutable length of one yard. The legal standard of one troy pound is missing. We have therefore to report that it is absolutely necessary that steps be taken for the formation and legalising of new Standards of Length and Weight.

</ref> or changed.[Note 45] The other is that they largely cannot benefit from advancements in science and technology. The last artefact used by the SI was the International Prototype Kilogram (IPK), a particular cylinder of platinum-iridium; from 1889 to 2019, the kilogram was by definition equal to the mass of the IPK. Concerns regarding its stability on the one hand, and progress in precise measurements of the Planck constant and the Avogadro constant on the other, led to a revision of the definition of the base units, put into effect on 20 May 2019.[23] This was the biggest change in the SI system since it was first formally defined and established in 1960, and it resulted in the definitions described above.

In the past, there were also various other approaches to the definitions of some of the SI units. One made use of a specific physical state of a specific substance (the triple point of water, which was used in the definition of the kelvin[24]:113–4); others referred to idealised experimental prescriptions[2]:125 (as in the case of the former SI definition of the ampere[24]:113 and the former SI definition (originally enacted in 1979) of the candela[24]:115).

In the future, the set of defining constants used by the SI may be modified as more stable constants are found, or if it turns out that other constants can be more precisely measured.[Note 46]

History

The original motivation for the development of the SI was the diversity of units that had sprung up within the centimetre–gram–second (CGS) systems (specifically the inconsistency between the systems of electrostatic units and electromagnetic units) and the lack of coordination between the various disciplines that used them. The General Conference on Weights and Measures (French: Conférence générale des poids et mesures – CGPM), which was established by the Metre Convention of 1875, brought together many international organisations to establish the definitions and standards of a new system and to standardise the rules for writing and presenting measurements. The system was published in 1960 as a result of an initiative that began in 1948. It is based on the metre–kilogram–second system of units (MKS) rather than any variant of the CGS.

Controlling authority

The SI is regulated and continually developed by three international organisations that were established in 1875 under the terms of the Metre Convention. They are the General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM[Note 11]), the International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM[Note 12]), and the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM[Note 14]). The ultimate authority rests with the CGPM, which is a plenary body through which its Member States[Note 48] act together on matters related to measurement science and measurement standards; it usually convenes every four years.[25] The CGPM elects the CIPM, which is an 18-person committee of eminent scientists. The CIPM operates based on the advice of a number of its Consultative Committees, which bring together the world's experts in their specified fields as advisers on scientific and technical matters.[26][Note 49] One of these committees is the Consultative Committee for Units (CCU), which is responsible for matters related to the development of the International System of Units (SI), preparation of successive editions of the SI brochure, and advice to the CIPM on matters concerning units of measurement.[27] It is the CCU which considers in detail all new scientific and technological developments related to the definition of units and the SI. In practice, when it comes to the definition of the SI, the CGPM simply formally approves the recommendations of the CIPM, which, in turn, follows the advice of the CCU.

The CCU has the following as members:[28][29] national laboratories of the Member States of the CGPM charged with establishing national standards;[Note 50] relevant intergovernmental organisations and international bodies;[Note 51] international commissions or committees;[Note 52] scientific unions;[Note 53] personal members;[Note 54] and, as an ex officio member of all Consultative Committees, the Director of the BIPM.

All the decisions and recommendations concerning units are collected in a brochure called The International System of Units (SI)[2][Note 13], which is published by the BIPM and periodically updated.

Units and prefixes

The International System of Units consists of a set of base units, derived units, and a set of decimal-based multipliers that are used as prefixes.[24]:103–106 The units, excluding prefixed units,[Note 55] form a coherent system of units, which is based on a system of quantities in such a way that the equations between the numerical values expressed in coherent units have exactly the same form, including numerical factors, as the corresponding equations between the quantities. For example, 1 N = 1 kg × 1 m/s2 says that one newton is the force required to accelerate a mass of one kilogram at one metre per second squared, as related through the principle of coherence to the equation relating the corresponding quantities: F = m × a.

Derived units apply to derived quantities, which may by definition be expressed in terms of base quantities, and thus are not independent; for example, electrical conductance is the inverse of electrical resistance, with the consequence that the siemens is the inverse of the ohm, and similarly, the ohm and siemens can be replaced with a ratio of an ampere and a volt, because those quantities bear a defined relationship to each other.[Note 56] Other useful derived quantities can be specified in terms of the SI base and derived units that have no named units in the SI system, such as acceleration, which is defined in SI units as m/s2.

Base units

The SI base units are the building blocks of the system and all the other units are derived from them.

| Unit name |

Unit symbol |

Dimension symbol |

Quantity name |

Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| second [n 1] |

s | T | time | The duration of 9192631770 periods of the radiation corresponding to the transition between the two hyperfine levels of the ground state of the caesium-133 atom. |

| metre | m | L | length | The distance travelled by light in vacuum in 1/299792458 second. |

| kilogram [n 2] |

kg | M | mass | The kilogram is defined by setting the Planck constant h exactly to 6.62607015×10−34 J⋅s (J = kg⋅m2⋅s−2), given the definitions of the metre and the second.[23] |

| ampere | A | I | electric current | The flow of 1/1.602176634×10−19 times the elementary charge e per second. |

| kelvin | K | Θ | thermodynamic temperature |

The kelvin is defined by setting the fixed numerical value of the Boltzmann constant k to 1.380649×10−23 J⋅K−1, (J = kg⋅m2⋅s−2), given the definition of the kilogram, the metre, and the second. |

| mole | mol | N | amount of substance |

The amount of substance of exactly 6.02214076×1023 elementary entities.[n 3] This number is the fixed numerical value of the Avogadro constant, NA, when expressed in the unit mol−1. |

| candela | cd | J | luminous intensity |

The luminous intensity, in a given direction, of a source that emits monochromatic radiation of frequency 5.4×1014 hertz and that has a radiant intensity in that direction of 1/683 watt per steradian. |

| ||||

Derived units

The derived units in the SI are formed by powers, products, or quotients of the base units and are potentially unlimited in number.[24]:103[32]:14,16 Derived units are associated with derived quantities; for example, velocity is a quantity that is derived from the base quantities of time and length, and thus the SI derived unit is metre per second (symbol m/s). The dimensions of derived units can be expressed in terms of the dimensions of the base units.

Combinations of base and derived units may be used to express other derived units. For example, the SI unit of force is the newton (N), the SI unit of pressure is the pascal (Pa)—and the pascal can be defined as one newton per square metre (N/m2).[35]

| Name | Symbol | Quantity | In SI base units | In other SI units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| radian[N 1] | rad | plane angle | m/m | 1 |

| steradian[N 1] | sr | solid angle | m2/m2 | 1 |

| hertz | Hz | frequency | s−1 | |

| newton | N | force, weight | kg⋅m⋅s−2 | |

| pascal | Pa | pressure, stress | kg⋅m−1⋅s−2 | N/m2 |

| joule | J | energy, work, heat | kg⋅m2⋅s−2 | N⋅m = Pa⋅m3 |

| watt | W | power, radiant flux | kg⋅m2⋅s−3 | J/s |

| coulomb | C | electric charge | s⋅A | |

| volt | V | electrical potential difference (voltage), emf | kg⋅m2⋅s−3⋅A−1 | W/A = J/C |

| farad | F | capacitance | kg−1⋅m−2⋅s4⋅A2 | C/V |

| ohm | Ω | resistance, impedance, reactance | kg⋅m2⋅s−3⋅A−2 | V/A |

| siemens | S | electrical conductance | kg−1⋅m−2⋅s3⋅A2 | Ω−1 |

| weber | Wb | magnetic flux | kg⋅m2⋅s−2⋅A−1 | V⋅s |

| tesla | T | magnetic flux density | kg⋅s−2⋅A−1 | Wb/m2 |

| henry | H | inductance | kg⋅m2⋅s−2⋅A−2 | Wb/A |

| degree Celsius | °C | temperature relative to 273.15 K | K | |

| lumen | lm | luminous flux | cd⋅sr | cd⋅sr |

| lux | lx | illuminance | m−2⋅cd | lm/m2 |

| becquerel | Bq | radioactivity (decays per unit time) | s−1 | |

| gray | Gy | absorbed dose (of ionising radiation) | m2⋅s−2 | J/kg |

| sievert | Sv | equivalent dose (of ionising radiation) | m2⋅s−2 | J/kg |

| katal | kat | catalytic activity | mol⋅s−1 | |

Notes

| ||||

| Name | Symbol | Derived quantity | Typical symbol |

|---|---|---|---|

| square metre | m2 | area | A |

| cubic metre | m3 | volume | V |

| metre per second | m/s | speed, velocity | v |

| metre per second squared | m/s2 | acceleration | a |

| reciprocal metre | m−1 | wavenumber | σ, ṽ |

| vergence (optics) | V, 1/f | ||

| kilogram per cubic metre | kg/m3 | density | ρ |

| kilogram per square metre | kg/m2 | surface density | ρA |

| cubic metre per kilogram | m3/kg | specific volume | v |

| ampere per square metre | A/m2 | current density | j |

| ampere per metre | A/m | magnetic field strength | H |

| mole per cubic metre | mol/m3 | concentration | c |

| kilogram per cubic metre | kg/m3 | mass concentration | ρ, γ |

| candela per square metre | cd/m2 | luminance | Lv |

| Name | Symbol | Quantity | In SI base units |

|---|---|---|---|

| pascal-second | Pa⋅s | dynamic viscosity | m−1⋅kg⋅s−1 |

| newton-metre | N⋅m | moment of force | m2⋅kg⋅s−2 |

| newton per metre | N/m | surface tension | kg⋅s−2 |

| radian per second | rad/s | angular velocity, angular frequency | s−1 |

| radian per second squared | rad/s2 | angular acceleration | s−2 |

| watt per square metre | W/m2 | heat flux density, irradiance | kg⋅s−3 |

| joule per kelvin | J/K | entropy, heat capacity | m2⋅kg⋅s−2⋅K−1 |

| joule per kilogram-kelvin | J/(kg⋅K) | specific heat capacity, specific entropy | m2⋅s−2⋅K−1 |

| joule per kilogram | J/kg | specific energy | m2⋅s−2 |

| watt per metre-kelvin | W/(m⋅K) | thermal conductivity | m⋅kg⋅s−3⋅K−1 |

| joule per cubic metre | J/m3 | energy density | m−1⋅kg⋅s−2 |

| volt per metre | V/m | electric field strength | m⋅kg⋅s−3⋅A−1 |

| coulomb per cubic metre | C/m3 | electric charge density | m−3⋅s⋅A |

| coulomb per square metre | C/m2 | surface charge density, electric flux density, electric displacement | m−2⋅s⋅A |

| farad per metre | F/m | permittivity | m−3⋅kg−1⋅s4⋅A2 |

| henry per metre | H/m | permeability | m⋅kg⋅s−2⋅A−2 |

| joule per mole | J/mol | molar energy | m2⋅kg⋅s−2⋅mol−1 |

| joule per mole-kelvin | J/(mol⋅K) | molar entropy, molar heat capacity | m2⋅kg⋅s−2⋅K−1⋅mol−1 |

| coulomb per kilogram | C/kg | exposure (x- and γ-rays) | kg−1⋅s⋅A |

| gray per second | Gy/s | absorbed dose rate | m2⋅s−3 |

| watt per steradian | W/sr | radiant intensity | m2⋅kg⋅s−3 |

| watt per square metre-steradian | W/(m2⋅sr) | radiance | kg⋅s−3 |

| katal per cubic metre | kat/m3 | catalytic activity concentration | m−3⋅s−1⋅mol |

Prefixes

Prefixes are added to unit names to produce multiples and submultiples of the original unit. All of these are integer powers of ten, and above a hundred or below a hundredth all are integer powers of a thousand. For example, kilo- denotes a multiple of a thousand and milli- denotes a multiple of a thousandth, so there are one thousand millimetres to the metre and one thousand metres to the kilometre. The prefixes are never combined, so for example a millionth of a metre is a micrometre, not a millimillimetre. Multiples of the kilogram are named as if the gram were the base unit, so a millionth of a kilogram is a milligram, not a microkilogram.[24]:122[36]:14 When prefixes are used to form multiples and submultiples of SI base and derived units, the resulting units are no longer coherent.[24]:7

The BIPM specifies 20 prefixes for the International System of Units (SI):

| Prefix | Base 10 | Decimal | English word | Adoption[nb 1] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Symbol | Short scale | Long scale | ||||

| yotta | Y | 1024 | 1000000000000000000000000 | septillion | quadrillion | 1991 | |

| zetta | Z | 1021 | 1000000000000000000000 | sextillion | trilliard | 1991 | |

| exa | E | 1018 | 1000000000000000000 | quintillion | trillion | 1975 | |

| peta | P | 1015 | 1000000000000000 | quadrillion | billiard | 1975 | |

| tera | T | 1012 | 1000000000000 | trillion | billion | 1960 | |

| giga | G | 109 | 1000000000 | billion | milliard | 1960 | |

| mega | M | 106 | 1000000 | million | 1873 | ||

| kilo | k | 103 | 1000 | thousand | 1795 | ||

| hecto | h | 102 | 100 | hundred | 1795 | ||

| deca | da | 101 | 10 | ten | 1795 | ||

| 100 | 1 | one | – | ||||

| deci | d | 10−1 | 0.1 | tenth | 1795 | ||

| centi | c | 10−2 | 0.01 | hundredth | 1795 | ||

| milli | m | 10−3 | 0.001 | thousandth | 1795 | ||

| micro | μ | 10−6 | 0.000001 | millionth | 1873 | ||

| nano | n | 10−9 | 0.000000001 | billionth | milliardth | 1960 | |

| pico | p | 10−12 | 0.000000000001 | trillionth | billionth | 1960 | |

| femto | f | 10−15 | 0.000000000000001 | quadrillionth | billiardth | 1964 | |

| atto | a | 10−18 | 0.000000000000000001 | quintillionth | trillionth | 1964 | |

| zepto | z | 10−21 | 0.000000000000000000001 | sextillionth | trilliardth | 1991 | |

| yocto | y | 10−24 | 0.000000000000000000000001 | septillionth | quadrillionth | 1991 | |

| |||||||

Non-SI units accepted for use with SI

Many non-SI units continue to be used in the scientific, technical, and commercial literature. Some units are deeply embedded in history and culture, and their use has not been entirely replaced by their SI alternatives. The CIPM recognised and acknowledged such traditions by compiling a list of non-SI units accepted for use with SI:[24]

Some units of time, angle, and legacy non-SI units have a long history of use. Most societies have used the solar day and its non-decimal subdivisions as a basis of time and, unlike the foot or the pound, these were the same regardless of where they were being measured. The radian, being 1/2π of a revolution, has mathematical advantages but is rarely used for navigation. Further, the units used in navigation around the world are similar. The tonne, litre, and hectare were adopted by the CGPM in 1879 and have been retained as units that may be used alongside SI units, having been given unique symbols. The catalogued units are given below:

| Quantity | Name | Symbol | Value in SI units |

|---|---|---|---|

| time | minute | min | 1 min = 60 s |

| hour | h | 1 h = 60 min = 3600 s | |

| day | d | 1 d = 24 h = 86400 s | |

| length | astronomical unit | au | 1 au = 149597870700 m |

| plane and phase angle |

degree | ° | 1° = (π/180) rad |

| minute | ′ | 1′ = (1/60)° = (π/10800) rad | |

| second | ″ | 1″ = (1/60)′ = (π/648000) rad | |

| area | hectare | ha | 1 ha = 1 hm2 = 104 m2 |

| volume | litre | l, L | 1 l = 1 L = 1 dm3 = 103 cm3 = 10−3 m3 |

| mass | tonne (metric ton) | t | 1 t = 1 000 kg |

| dalton | Da | 1 Da = 1.660539040(20)×10−27 kg | |

| energy | electronvolt | eV | 1 eV = 1.602176634×10−19 J |

| logarithmic ratio quantities |

neper | Np | In using these units it is important that the nature of the quantity be specified and that any reference value used be specified. |

| bel | B | ||

| decibel | dB |

These units are used in combination with SI units in common units such as the kilowatt-hour (1 kW⋅h = 3.6 MJ).

Common notions of the metric units

The basic units of the metric system, as originally defined, represented common quantities or relationships in nature. They still do – the modern precisely defined quantities are refinements of definition and methodology, but still with the same magnitudes. In cases where laboratory precision may not be required or available, or where approximations are good enough, the original definitions may suffice.[Note 57]

- A second is 1/60 of a minute, which is 1/60 of an hour, which is 1/24 of a day, so a second is 1/86400 of a day (the use of base 60 dates back to Babylonian times); a second is the time it takes a dense object to freely fall 4.9 metres from rest.[Note 58]

- The length of the equator is close to 40000000 m (more precisely 40075014.2 m).[37] In fact, the dimensions of our planet were used by the French Academy in the original definition of the metre.[38]

- The metre is close to the length of a pendulum that has a period of 2 seconds;[Note 59] most dining tabletops are about 0.75 metres high;[39] a very tall human (basketball forward) is about 2 metres tall.[40]

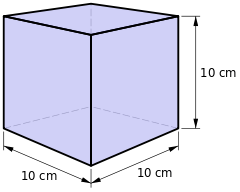

- The kilogram is the mass of a litre of cold water; a cubic centimetre or millilitre of water has a mass of one gram; a 1-euro coin weighs 7.5 g;[41] a Sacagawea US 1-dollar coin weighs 8.1 g;[42] a UK 50-pence coin weighs 8.0 g.[43]

- A candela is about the luminous intensity of a moderately bright candle, or 1 candle power; a 60 W tungsten-filament incandescent light bulb has a luminous intensity of about 64 candela.[Note 60]

- A mole of a substance has a mass that is its molecular mass expressed in units of grams; the mass of a mole of carbon is 12.0 g, and the mass of a mole of table salt is 58.4 g.

- Since all gases have the same volume per mole at a given temperature and pressure far from their points of liquefaction and solidification (see Perfect gas), and air is about 1/5 oxygen (molecular mass 32) and 4/5 nitrogen (molecular mass 28), the density of any near-perfect gas relative to air can be obtained to a good approximation by dividing its molecular mass by 29 (because 4/5 × 28 + 1/5 × 32 = 28.8 ≈ 29). For example, carbon monoxide (molecular mass 28) has almost the same density as air.

- A temperature difference of one kelvin is the same as one degree Celsius: 1/100 of the temperature differential between the freezing and boiling points of water at sea level; the absolute temperature in kelvins is the temperature in degrees Celsius plus about 273; human body temperature is about 37 °C or 310 K.

- A 60 W incandescent light bulb rated at 120 V (US mains voltage) consumes 0.5 A at this voltage. A 60 W bulb rated at 240 V (European mains voltage) consumes 0.25 A at this voltage.[Note 61]

Lexicographic conventions

Unit names

The symbols for the SI units are intended to be identical, regardless of the language used,[24]:130–135 but names are ordinary nouns and use the character set and follow the grammatical rules of the language concerned. Names of units follow the grammatical rules associated with common nouns: in English and in French they start with a lowercase letter (e.g., newton, hertz, pascal), even when the unit is named after a person and its symbol begins with a capital letter.[24]:148 This also applies to "degrees Celsius", since "degree" is the beginning of the unit.[45][46] The only exceptions are in the beginning of sentences and in headings and publication titles.[24]:148 The English spelling for certain SI units differs: US English uses the spelling deka-, meter, and liter, whilst International English uses deca-, metre, and litre.

Unit symbols and the values of quantities

Although the writing of unit names is language-specific, the writing of unit symbols and the values of quantities is consistent across all languages and therefore the SI Brochure has specific rules in respect of writing them.[24]:130–135 The guideline produced by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)[47] clarifies language-specific areas in respect of American English that were left open by the SI Brochure, but is otherwise identical to the SI Brochure.[48]

General rules

General rules[Note 62] for writing SI units and quantities apply to text that is either handwritten or produced using an automated process:

- The value of a quantity is written as a number followed by a space (representing a multiplication sign) and a unit symbol; e.g., 2.21 kg, 7.3×102 m2, 22 K. This rule explicitly includes the percent sign (%)[24]:134 and the symbol for degrees Celsius (°C).[24]:133 Exceptions are the symbols for plane angular degrees, minutes, and seconds (°, ′, and ″, respectively), which are placed immediately after the number with no intervening space.

- Symbols are mathematical entities, not abbreviations, and as such do not have an appended period/full stop (.), unless the rules of grammar demand one for another reason, such as denoting the end of a sentence.

- A prefix is part of the unit, and its symbol is prepended to a unit symbol without a separator (e.g., k in km, M in MPa, G in GHz, μ in μg). Compound prefixes are not allowed. A prefixed unit is atomic in expressions (e.g., km2 is equivalent to (km)2).

- Unit symbols are written using roman (upright) type, regardless of the type used in the surrounding text.

- Symbols for derived units formed by multiplication are joined with a centre dot (⋅) or a non-breaking space; e.g., N⋅m or N m.

- Symbols for derived units formed by division are joined with a solidus (/), or given as a negative exponent. E.g., the "metre per second" can be written m/s, m s−1, m⋅s−1, or m/s. A solidus must not be used more than once in a given expression without parentheses to remove ambiguities; e.g., kg/(m⋅s2) and kg⋅m−1⋅s−2 are acceptable, but kg/m/s2 is ambiguous and unacceptable.

- The first letter of symbols for units derived from the name of a person is written in upper case; otherwise, they are written in lower case. E.g., the unit of pressure is named after Blaise Pascal, so its symbol is written "Pa", but the symbol for mole is written "mol". Thus, "T" is the symbol for tesla, a measure of magnetic field strength, and "t" the symbol for tonne, a measure of mass. Since 1979, the litre may exceptionally be written using either an uppercase "L" or a lowercase "l", a decision prompted by the similarity of the lowercase letter "l" to the numeral "1", especially with certain typefaces or English-style handwriting. The American NIST recommends that within the United States "L" be used rather than "l".

- Symbols do not have a plural form, e.g., 25 kg, but not 25 kgs.

- Uppercase and lowercase prefixes are not interchangeable. E.g., the quantities 1 mW and 1 MW represent two different quantities (milliwatt and megawatt).

- The symbol for the decimal marker is either a point or comma on the line. In practice, the decimal point is used in most English-speaking countries and most of Asia, and the comma in most of Latin America and in continental European countries.[49]

- Spaces should be used as a thousands separator (1000000) in contrast to commas or periods (1,000,000 or 1.000.000) to reduce confusion resulting from the variation between these forms in different countries.

- Any line-break inside a number, inside a compound unit, or between number and unit should be avoided. Where this is not possible, line breaks should coincide with thousands separators.

- Because the value of "billion" and "trillion" varies between languages, the dimensionless terms "ppb" (parts per billion) and "ppt" (parts per trillion) should be avoided. The SI Brochure does not suggest alternatives.

Printing SI symbols

The rules covering printing of quantities and units are part of ISO 80000-1:2009.[50]

Further rules[Note 62] are specified in respect of production of text using printing presses, word processors, typewriters, and the like.

International System of Quantities

- SI Brochure

The CGPM publishes a brochure that defines and presents the SI.[24] Its official version is in French, in line with the Metre Convention.[24]:102 It leaves some scope for local variations, particularly regarding unit names and terms in different languages.[Note 63][32]

The writing and maintenance of the CGPM brochure is carried out by one of the committees of the International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM). The definitions of the terms "quantity", "unit", "dimension" etc. that are used in the SI Brochure are those given in the International vocabulary of metrology.[51]

The quantities and equations that provide the context in which the SI units are defined are now referred to as the International System of Quantities (ISQ). The ISQ is based on the quantities underlying each of the seven base units of the SI. Other quantities, such as area, pressure, and electrical resistance, are derived from these base quantities by clear non-contradictory equations. The ISQ defines the quantities that are measured with the SI units.[52] The ISQ is formalised, in part, in the international standard ISO/IEC 80000, which was completed in 2009 with the publication of ISO 80000-1,[53] and has largely been revised in 2019–2020 with the remainder being under review.

Realisation of units

Metrologists carefully distinguish between the definition of a unit and its realisation. The definition of each base unit of the SI is drawn up so that it is unique and provides a sound theoretical basis on which the most accurate and reproducible measurements can be made. The realisation of the definition of a unit is the procedure by which the definition may be used to establish the value and associated uncertainty of a quantity of the same kind as the unit. A description of the mise en pratique[Note 64] of the base units is given in an electronic appendix to the SI Brochure.[55][24]:168–169

The published mise en pratique is not the only way in which a base unit can be determined: the SI Brochure states that "any method consistent with the laws of physics could be used to realise any SI unit."[24]:111 In the current (2016) exercise to overhaul the definitions of the base units, various consultative committees of the CIPM have required that more than one mise en pratique shall be developed for determining the value of each unit.[56] In particular:

- At least three separate experiments be carried out yielding values having a relative standard uncertainty in the determination of the kilogram of no more than 5×10−8 and at least one of these values should be better than 2×10−8. Both the Kibble balance and the Avogadro project should be included in the experiments and any differences between these be reconciled.[57][58]

- When the kelvin is being determined, the relative uncertainty of the Boltzmann constant derived from two fundamentally different methods such as acoustic gas thermometry and dielectric constant gas thermometry be better than one part in 10−6 and that these values be corroborated by other measurements.[59]

Evolution of the SI

Changes to the SI

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM) has described SI as "the modern form of metric system".[24]:95 Changing technology has led to an evolution of the definitions and standards that has followed two principal strands – changes to SI itself, and clarification of how to use units of measure that are not part of SI but are still nevertheless used on a worldwide basis.

Since 1960 the CGPM has made a number of changes to the SI to meet the needs of specific fields, notably chemistry and radiometry. These are mostly additions to the list of named derived units, and include the mole (symbol mol) for an amount of substance, the pascal (symbol Pa) for pressure, the siemens (symbol S) for electrical conductance, the becquerel (symbol Bq) for "activity referred to a radionuclide", the gray (symbol Gy) for ionising radiation, the sievert (symbol Sv) as the unit of dose equivalent radiation, and the katal (symbol kat) for catalytic activity.[24]:156[60][24]:156[24]:158[24]:159[24]:165

The range of defined prefixes pico- (10−12) to tera- (1012) was extended to 10−24 to 1024.[24]:152[24]:158[24]:164

The 1960 definition of the standard metre in terms of wavelengths of a specific emission of the krypton 86 atom was replaced with the distance that light travels in vacuum in exactly 1/299792458 second, so that the speed of light is now an exactly specified constant of nature.

A few changes to notation conventions have also been made to alleviate lexicographic ambiguities. An analysis under the aegis of CSIRO, published in 2009 by the Royal Society, has pointed out the opportunities to finish the realisation of that goal, to the point of universal zero-ambiguity machine readability.[61]

2019 redefinitions

After the metre was redefined in 1960, the International Prototype of the Kilogram (IPK) was the only physical artefact upon which base units (directly the kilogram and indirectly the ampere, mole and candela) depended for their definition, making these units subject to periodic comparisons of national standard kilograms with the IPK.[62] During the 2nd and 3rd Periodic Verification of National Prototypes of the Kilogram, a significant divergence had occurred between the mass of the IPK and all of its official copies stored around the world: the copies had all noticeably increased in mass with respect to the IPK. During extraordinary verifications carried out in 2014 preparatory to redefinition of metric standards, continuing divergence was not confirmed. Nonetheless, the residual and irreducible instability of a physical IPK undermined the reliability of the entire metric system to precision measurement from small (atomic) to large (astrophysical) scales.

A proposal was made that:

- In addition to the speed of light, four constants of nature – the Planck constant, an elementary charge, the Boltzmann constant, and the Avogadro number – be defined to have exact values

- The International Prototype of the Kilogram be retired

- The current definitions of the kilogram, ampere, kelvin, and mole be revised

- The wording of base unit definitions should change emphasis from explicit unit to explicit constant definitions.

The new definitions were adopted at the 26th CGPM on 16 November 2018, and came into effect on 20 May 2019.[63] The change was adopted by the European Union through Directive (EU) 2019/1258.[64]

History

The improvisation of units

The units and unit magnitudes of the metric system which became the SI were improvised piecemeal from everyday physical quantities starting in the mid-18th century. Only later were they moulded into an orthogonal coherent decimal system of measurement.

The degree centigrade as a unit of temperature resulted from the scale devised by Swedish astronomer Anders Celsius in 1742. His scale counter-intuitively designated 100 as the freezing point of water and 0 as the boiling point. Independently, in 1743, the French physicist Jean-Pierre Christin described a scale with 0 as the freezing point of water and 100 the boiling point. The scale became known as the centi-grade, or 100 gradations of temperature, scale.

The metric system was developed from 1791 onwards by a committee of the French Academy of Sciences, commissioned to create a unified and rational system of measures.[66] The group, which included preeminent French men of science,[67]:89 used the same principles for relating length, volume, and mass that had been proposed by the English clergyman John Wilkins in 1668[68][69] and the concept of using the Earth's meridian as the basis of the definition of length, originally proposed in 1670 by the French abbot Mouton.[70][71]

In March 1791, the Assembly adopted the committee's proposed principles for the new decimal system of measure including the metre defined to be 1/10,000,000 of the length of the quadrant of earth's meridian passing through Paris, and authorised a survey to precisely establish the length of the meridian. In July 1792, the committee proposed the names metre, are, litre and grave for the units of length, area, capacity, and mass, respectively. The committee also proposed that multiples and submultiples of these units were to be denoted by decimal-based prefixes such as centi for a hundredth and kilo for a thousand.[72]:82

Later, during the process of adoption of the metric system, the Latin gramme and kilogramme, replaced the former provincial terms gravet (1/1000 grave) and grave. In June 1799, based on the results of the meridian survey, the standard mètre des Archives and kilogramme des Archives were deposited in the French National Archives. Subsequently, that year, the metric system was adopted by law in France.[78] [79] The French system was short-lived due to its unpopularity. Napoleon ridiculed it, and in 1812, introduced a replacement system, the mesures usuelles or "customary measures" which restored many of the old units, but redefined in terms of the metric system.

During the first half of the 19th century there was little consistency in the choice of preferred multiples of the base units: typically the myriametre (10000 metres) was in widespread use in both France and parts of Germany, while the kilogram (1000 grams) rather than the myriagram was used for mass.[65]

In 1832, the German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss, assisted by Wilhelm Weber, implicitly defined the second as a base unit when he quoted the Earth's magnetic field in terms of millimetres, grams, and seconds.[73] Prior to this, the strength of the Earth's magnetic field had only been described in relative terms. The technique used by Gauss was to equate the torque induced on a suspended magnet of known mass by the Earth's magnetic field with the torque induced on an equivalent system under gravity. The resultant calculations enabled him to assign dimensions based on mass, length and time to the magnetic field.[Note 65][80]

A candlepower as a unit of illuminance was originally defined by an 1860 English law as the light produced by a pure spermaceti candle weighing 1⁄6 pound (76 grams) and burning at a specified rate. Spermaceti, a waxy substance found in the heads of sperm whales, was once used to make high-quality candles. At this time the French standard of light was based upon the illumination from a Carcel oil lamp. The unit was defined as that illumination emanating from a lamp burning pure rapeseed oil at a defined rate. It was accepted that ten standard candles were about equal to one Carcel lamp.

Metre Convention

A French-inspired initiative for international cooperation in metrology led to the signing in 1875 of the Metre Convention, also called Treaty of the Metre, by 17 nations.[Note 66][67]:353–354 Initially the convention only covered standards for the metre and the kilogram. In 1921, the Metre Convention was extended to include all physical units, including the ampere and others thereby enabling the CGPM to address inconsistencies in the way that the metric system had been used.[74][24]:96

A set of 30 prototypes of the metre and 40 prototypes of the kilogram,[Note 67] in each case made of a 90% platinum-10% iridium alloy, were manufactured by British metallurgy specialty firm and accepted by the CGPM in 1889. One of each was selected at random to become the International prototype metre and International prototype kilogram that replaced the mètre des Archives and kilogramme des Archives respectively. Each member state was entitled to one of each of the remaining prototypes to serve as the national prototype for that country.[81]

The treaty also established a number of international organisations to oversee the keeping of international standards of measurement:[82] [83]

The CGS and MKS systems

In the 1860s, James Clerk Maxwell, William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) and others working under the auspices of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, built on Gauss's work and formalised the concept of a coherent system of units with base units and derived units christened the centimetre–gram–second system of units in 1874. The principle of coherence was successfully used to define a number of units of measure based on the CGS, including the erg for energy, the dyne for force, the barye for pressure, the poise for dynamic viscosity and the stokes for kinematic viscosity.[76]

In 1879, the CIPM published recommendations for writing the symbols for length, area, volume and mass, but it was outside its domain to publish recommendations for other quantities. Beginning in about 1900, physicists who had been using the symbol "μ" (mu) for "micrometre" or "micron", "λ" (lambda) for "microlitre", and "γ" (gamma) for "microgram" started to use the symbols "μm", "μL" and "μg".[84]

At the close of the 19th century three different systems of units of measure existed for electrical measurements: a CGS-based system for electrostatic units, also known as the Gaussian or ESU system, a CGS-based system for electromechanical units (EMU) and an International system based on units defined by the Metre Convention.[85] for electrical distribution systems. Attempts to resolve the electrical units in terms of length, mass, and time using dimensional analysis was beset with difficulties—the dimensions depended on whether one used the ESU or EMU systems.[77] This anomaly was resolved in 1901 when Giovanni Giorgi published a paper in which he advocated using a fourth base unit alongside the existing three base units. The fourth unit could be chosen to be electric current, voltage, or electrical resistance.[86] Electric current with named unit 'ampere' was chosen as the base unit, and the other electrical quantities derived from it according to the laws of physics. This became the foundation of the MKS system of units.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a number of non-coherent units of measure based on the gram/kilogram, centimetre/metre, and second, such as the Pferdestärke (metric horsepower) for power,[87][Note 68] the darcy for permeability[88] and "millimetres of mercury" for barometric and blood pressure were developed or propagated, some of which incorporated standard gravity in their definitions.[Note 69]

At the end of the Second World War, a number of different systems of measurement were in use throughout the world. Some of these systems were metric system variations; others were based on customary systems of measure, like the U.S customary system and Imperial system of the UK and British Empire.

The Practical system of units

In 1948, the 9th CGPM commissioned a study to assess the measurement needs of the scientific, technical, and educational communities and "to make recommendations for a single practical system of units of measurement, suitable for adoption by all countries adhering to the Metre Convention".[89] This working document was Practical system of units of measurement. Based on this study, the 10th CGPM in 1954 defined an international system derived from six base units including units of temperature and optical radiation in addition to those for the MKS system mass, length, and time units and Giorgi's current unit. Six base units were recommended: the metre, kilogram, second, ampere, degree Kelvin, and candela.

The 9th CGPM also approved the first formal recommendation for the writing of symbols in the metric system when the basis of the rules as they are now known was laid down.[90] These rules were subsequently extended and now cover unit symbols and names, prefix symbols and names, how quantity symbols should be written and used, and how the values of quantities should be expressed.[24]:104,130

Birth of the SI

In 1960, the 11th CGPM synthesised the results of the 12-year study into a set of 16 resolutions. The system was named the International System of Units, abbreviated SI from the French name, Le Système International d'Unités.[24]:110[91]

Historical definitions

When Maxwell first introduced the concept of a coherent system, he identified three quantities that could be used as base units: mass, length, and time. Giorgi later identified the need for an electrical base unit, for which the unit of electric current was chosen for SI. Another three base units (for temperature, amount of substance, and luminous intensity) were added later.

The early metric systems defined a unit of weight as a base unit, while the SI defines an analogous unit of mass. In everyday use, these are mostly interchangeable, but in scientific contexts the difference matters. Mass, strictly the inertial mass, represents a quantity of matter. It relates the acceleration of a body to the applied force via Newton's law, F = m × a: force equals mass times acceleration. A force of 1 N (newton) applied to a mass of 1 kg will accelerate it at 1 m/s2. This is true whether the object is floating in space or in a gravity field e.g. at the Earth's surface. Weight is the force exerted on a body by a gravitational field, and hence its weight depends on the strength of the gravitational field. Weight of a 1 kg mass at the Earth's surface is m × g; mass times the acceleration due to gravity, which is 9.81 newtons at the Earth's surface and is about 3.5 newtons at the surface of Mars. Since the acceleration due to gravity is local and varies by location and altitude on the Earth, weight is unsuitable for precision measurements of a property of a body, and this makes a unit of weight unsuitable as a base unit.

| Unit name |

Definition[n 1] |

|---|---|

| second |

|

| metre |

|

| kilogram |

|

| ampere |

|

| kelvin |

|

| mole |

|

| candela |

|

The Prior definitions of the various base units in the above table were made by the following authors and authorities:

All other definitions result from resolutions by either CGPM or the CIPM and are catalogued in the SI Brochure. | |

Metric units that are not recognised by the SI

Although the term metric system is often used as an informal alternative name for the International System of Units,[95] other metric systems exist, some of which were in widespread use in the past or are even still used in particular areas. There are also individual metric units such as the sverdrup that exist outside of any system of units. Most of the units of the other metric systems are not recognised by the SI.[Note 71][Note 73] Here are some examples. The centimetre–gram–second (CGS) system was the dominant metric system in the physical sciences and electrical engineering from the 1860s until at least the 1960s, and is still in use in some fields. It includes such SI-unrecognised units as the gal, dyne, erg, barye, etc. in its mechanical sector, as well as the poise and stokes in fluid dynamics. When it comes to the units for quantities in electricity and magnetism, there are several versions of the CGS system. Two of these are obsolete: the CGS electrostatic ('CGS-ESU', with the SI-unrecognised units of statcoulomb, statvolt, statampere, etc.) and the CGS electromagnetic system ('CGS-EMU', with abampere, abcoulomb, oersted, maxwell, abhenry, gilbert, etc.).[Note 74] A 'blend' of these two systems is still popular and is known as the Gaussian system (which includes the gauss as a special name for the CGS-EMU unit maxwell per square centimetre).[Note 75] In engineering (other than electrical engineering), there was formerly a long tradition of using the gravitational metric system, whose SI-unrecognised units include the kilogram-force (kilopond), technical atmosphere, metric horsepower, etc. The metre–tonne–second (mts) system, used in the Soviet Union from 1933 to 1955, had such SI-unrecognised units as the sthène, pièze, etc. Other groups of SI-unrecognised metric units are the various legacy and CGS units related to ionising radiation (rutherford, curie, roentgen, rad, rem, etc.), radiometry (langley, jansky), photometry (phot, nox, stilb, nit, metre-candle,[99]:17 lambert, apostilb, skot, brill, troland, talbot, candlepower, candle), thermodynamics (calorie), and spectroscopy (reciprocal centimetre). The angstrom is still used in various fields. Some other SI-unrecognised metric units that don't fit into any of the already mentioned categories include the are, bar, barn, fermi,[100]:20–21 gradian (gon, grad, or grade), metric carat, micron, millimetre of mercury, torr, millimetre (or centimetre, or metre) of water, millimicron, mho, stere, x unit, γ (unit of mass), γ (unit of magnetic flux density), and λ (unit of volume). In some cases, the SI-unrecognised metric units have equivalent SI units formed by combining a metric prefix with a coherent SI unit. For example, 1 γ (unit of magnetic flux density) = 1 nT, 1 Gal = 1 cm⋅s−2, 1 barye = 1 decipascal, etc. (a related group are the correspondences[Note 74] such as 1 abampere ≘ 1 decaampere, 1 abhenry ≘ 1 nanohenry, etc.[Note 76]). Sometimes it is not even a matter of a metric prefix: the SI-nonrecognised unit may be exactly the same as an SI coherent unit, except for the fact that the SI does not recognise the special name and symbol. For example, the nit is just an SI-unrecognised name for the SI unit candela per square metre and the talbot is an SI-unrecognised name for the SI unit lumen second. Frequently, a non-SI metric unit is related to an SI unit through a power of ten factor, but not one that has a metric prefix, e.g. 1 dyn = 10−5 newton, 1 Å = 10−10 m, etc. (and correspondences[Note 74] like 1 gauss ≘ 10−4 tesla). Finally, there are metric units whose conversion factors to SI units are not powers of ten, e.g. 1 calorie = 4.184 joules and 1 kilogram-force = 9.806650 newtons. Some SI-unrecognised metric units are still frequently used, e.g. the calorie (in nutrition), the rem (in the U.S.), the jansky (in radio astronomy), the reciprocal centimetre (in spectroscopy), the gauss (in industry) and the CGS-Gaussian units[Note 75] more generally (in some subfields of physics), the metric horsepower (for engine power, in Europe), the kilogram-force (for rocket engine thrust, in China and sometimes in Europe), etc. Others are now rarely used, such as the sthène and the rutherford.

See also

- Conversion of units – Comparison of various scales

- Introduction to the metric system

- Outline of the metric system – Overview of and topical guide to the metric system

- List of international common standards – Wikipedia list article

Organisations

- International Bureau of Weights and Measures – Intergovernmental measurement science and measurement standards setting organisation

- Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements (EU)

- National Institute of Standards and Technology – Measurement standards laboratory in the United States (US)

Standards and conventions

- Conventional electrical unit

- Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) – Primary time standard by which the world regulates clocks and time

- Unified Code for Units of Measure

Notes

- For example, the SI unit of velocity is the metre per second, m⋅s−1; of acceleration is the metre per second squared, m⋅s−2; etc.

- For example the newton (N), the unit of force, equivalent to kg⋅m⋅s−2; the joule (J), the unit of energy, equivalent to kg⋅m2⋅s−2, etc. The most recently named derived unit, the katal, was defined in 1999.

- For example, the recommended unit for the electric field strength is the volt per metre, V/m, where the volt is the derived unit for electric potential difference. The volt per metre is equal to kg⋅m⋅s−3⋅A−1 when expressed in terms of base units.

- Meaning that different units for a given quantity, such as length, are related by factors of 10. Therefore, calculations involve the simple process of moving the decimal point to the right or to the left.[3]

For example, the basic SI unit of length is the metre, which is about the height of the kitchen counter. But if one wishes to talk about driving distances using the SI units, one will normally use kilometres, where one kilometre is 1000 metres. On the other hand, tailoring measurements would usually be expressed in centimetres, where one centimetre is 1/100 of a metre. - Although the terms the metric system and the SI system are often used as synonyms, there are in fact many different, mutually incompatible types of metric systems. Moreover, there even exist some individual metric units that are not recognised by any larger metric system. See the section Metric units that are not recognised by the SI, below.

- As of May 2020, only for the following countries is it uncertain whether the SI system has any official status: Myanmar, Liberia, the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, Palau, and Samoa.

- It shall be lawful throughout the United States of America to employ the weights and measures of the metric system; and no contract or dealing, or pleading in any court, shall be deemed invalid or liable to objection because the weights or measures expressed or referred to therein are weights or measures of the metric system.

- In the US, the history of legislation begins with the Metric Act of 1866, which legally protected use of the metric system in commerce. The first section is still part of US law (15 U.S.C. § 204).[Note 7] In 1875, the US became one of the original signatories of the Metre Convention. In 1893, the Mendenhall Order stated that the Office of Weights and Measures… will in the future regard the International Prototype Metre and Kilogramme as fundamental standards, and the customary units — the yard and the pound — will be derived therefrom in accordance with the Act of July 28, 1866. In 1954, the US adopted the International Nautical Mile, which is defined as exactly 1852 m, in lieu of the U.S. Nautical Mile, defined as 6080.20 ft = 1853.248 m. In 1959, the U.S. National Bureau of Standards officially adapted the International yard and pound, which are defined exactly in terms of the metre and the kilogram. In 1968, the Metric Study Act (Pub. L. 90-472, August 9, 1968, 82 Stat. 693) authorised a three-year study of systems of measurement in the U.S., with particular emphasis on the feasibility of adopting the SI. The Metric Conversion Act of 1975 followed, later amended by the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988, the Savings in Construction Act of 1996, and the Department of Energy High-End Computing Revitalization Act of 2004. As a result of all these acts, the US current law (15 U.S.C. § 205b) states that

It is therefore the declared policy of the United States- (1) to designate the metric system of measurement as the preferred system of weights and measures for United States trade and commerce; (2) to require that each Federal agency, by a date certain and to the extent economically feasible by the end of the fiscal year 1992, use the metric system of measurement in its procurements, grants, and other business-related activities, except to the extent that such use is impractical or is likely to cause significant inefficiencies or loss of markets to United States firms, such as when foreign competitors are producing competing products in non-metric units; (3) to seek out ways to increase understanding of the metric system of measurement through educational information and guidance and in Government publications; and (4) to permit the continued use of traditional systems of weights and measures in non-business activities.

- And have been defined in terms of the SI's metric predecessors since at least the 1890s.

- See e.g. here for the various definitions of the catty, a traditional Chinese unit of mass, in various places across East and Southeast Asia. Similarly, see this article on the traditional Japanese units of measurement, as well as this one on the traditional Indian units of measurement.

- From French: Conférence générale des poids et mesures

- from French: Comité international des poids et mesures

- The SI Brochure for short. As of May 2020, the latest edition is the ninth, published in 2019. It is Ref. [2] of this article.

- from French: Bureau international des poids et mesures

- The latter are formalised in the International System of Quantities (ISQ).[2]:129

- Here are some examples of coherent derived SI units: the unit of velocity, which is the metre per second, with the symbol m/s; the unit of acceleration, which is the metre per second squared, with the symbol m/s2; etc.

- A useful property of a coherent system is that when the numerical values of physical quantities are expressed in terms of the units of the system, then the equations between the numerical values have exactly the same form, including numerical factors, as the corresponding equations between the physical quantities;[5]:6 An example may be useful to clarify this. Suppose we are given an equation relating some physical quantities, e.g. T = 1/2{m}{v}2, expressing the kinetic energy T in terms of the mass m and the velocity v. Choose a system of units, and let {T}, {m}, and {v} be the numerical values of T, m, and v when expressed in that system of units. If the system is coherent, then the numerical values will obey the same equation (including numerical factors) as the physical quantities, i.e. we will have that T = 1/2{m}{v}2.

On the other hand, if the chosen system of units is not coherent, this property may fail. For example, the following is not a coherent system: one where energy is measured in calories, while mass and velocity are measured in their SI units. After all, in that case, 1/2{m}{v}2 will give a numerical value whose meaning is the kinetic energy when expressed in joules, and that numerical value is different, by a factor of 4.184, from the numerical value when the kinetic energy is expressed in calories. Thus, in that system, the equation satisfied by the numerical values is instead {T} = 1/4.1841/2{m}{v}2. - For example the newton (N), the unit of force, equal to kg⋅m⋅s−2 when written in terms of the base units; the joule (J), the unit of energy, equal to kg⋅m2⋅s−2, etc. The most recently named derived unit, the katal, was defined in 1999.

- For example, the recommended unit for the electric field strength is the volt per metre, V/m, where the volt is the derived unit for electric potential difference. The volt per metre is equal to kg⋅m⋅s−3⋅A−1 when expressed in terms of base units.

- The SI base units (like the metre) are also called coherent units, because they belong to the set of coherent SI units.

- One kilometre is about 0.62 miles, a length equal to about two and a half laps around a typical athletic track. Walking at a moderate pace for one hour, an adult human will cover about five kilometres (about three miles). The distance from London, UK, to Paris, France is about 350 km; from London to New York, 5600 km.

- In other words, given any base unit or any coherent derived unit with a special name and symbol.

- Note, however, that there is a special group of units that are called non-SI units accepted for use with SI, most of which are not decimal multiples of the corresponding SI units; see below.

- Names and symbols for decimal multiples and sub-multiples of the unit of mass are formed as if it is the gram which is the base unit, i.e. by attaching prefix names and symbols, respectively, to the unit name "gram" and the unit symbol "g". For example, 10−6 kg is written as milligram, mg, not as microkilogram, μkg.[2]:144