Ruthenians

Ruthenians and Ruthenes are Latin exonyms formerly used in Western Europe for the ancestors of modern East Slavic peoples, especially the Rus' people with an Eastern Orthodox or Ruthenian Greek Catholic religious background.[1][2] The corresponding word in the Polish language is "rusini" and in Ukrainian language is "русини" (rusyny).[3]

A boy with the pilgrimage flag during the Ruthenian pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1906. | |

| Languages | |

|---|---|

| Previously Ruthenian; currently Belarusian, Ukrainian or Rusyn | |

| Religion | |

| Eastern Orthodox, Eastern Greek Catholic, Roman Catholic, Protestant | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other East Slavs |

Along with Lithuanians and Samogitians, Ruthenians constituted the main population of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which at its fullest extent was called the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Ruthenia and Samogitia (Ruthenian: Великое князство Литовское, Руское, Жомойтское и иных).[4]

From the 9th century, the "land of the Rus'", known later as Kievan Rus', was known in Western Europe by a variety of names derived from Rus'. In its broadest usage, "Ruthenians" or "Ruthenes" referred to peoples which were ancestors of the modern Belarusians, Rusyns and Ukrainians.

Geography

From the 9th century, the main Rus' state, which was known later as Kievan Rus' – and is now part of the modern states of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia – was known in Western Europe by a variety of names derived from Rus'. From the 12th century, the land of Rus' was usually known in Western Europe by the Latinised name Ruthenia.

Ruskaya zemlya, or Kievan Rus', also known as Ruthenia, c. 1230

Ruskaya zemlya, or Kievan Rus', also known as Ruthenia, c. 1230 1868 linguistic, ethnographic, and political map of Eastern Europe by Casimir DelamarreRuthenians and Ruthenian language

1868 linguistic, ethnographic, and political map of Eastern Europe by Casimir DelamarreRuthenians and Ruthenian language 1907 linguistic and ethnographic map that indicates Ukrainians as "Little Russians or Ruthenians"

1907 linguistic and ethnographic map that indicates Ukrainians as "Little Russians or Ruthenians" 1911 map depicting the Austro-Hungarian Empire, with Ruthenians in light green

1911 map depicting the Austro-Hungarian Empire, with Ruthenians in light green 1927 Polish map that indicates Ukrainians as "Ruthenians" ("Rusini"), and Belarusians as "White Ruthenians" ("Bialo Rusini").

1927 Polish map that indicates Ukrainians as "Ruthenians" ("Rusini"), and Belarusians as "White Ruthenians" ("Bialo Rusini").

History

One of the earliest references to Rus' in a Latinised form was in the 5th century, when King Odoacer styled himself as "Rex Rhutenorum".[5]

Ruteni, a misnomer that was also the name of an extinct and unrelated Celtic tribe in Ancient Gaul,[3] was used in reference to Rus' in the Annales Augustani of 1089.[3] An alternative early modern Latinisation, Rucenus (plural Ruceni) was, according to Boris Unbegaun, derived from Rusyn.[3] Baron Herberstein, describing the land of Russia, inhabited by the Rutheni who call themselves Russi, claimed that the first of the governors who rule Russia is the Grand Duke of Moscow, the second is the Grand Duke of Lithuania and the third is the King of Poland.[6][7] According to professor of Ukrainian origin John-Paul Himka from University of Alberta the word Rutheni did not include the modern Russians, who were known as Moscovitae.[3] Modern studies, however, indicate that even after the 16th century the word Rutheni was associated with all East Slavs. Vasili III of Russia, who ruled the Grand Duchy of Moscow in the 16th century, was known in European Latin sources as Rhuteni Imperator.[8] Jacques Margeret in his book "Estat de l'empire de Russie, et grande duché de Moscovie" of 1607 explained, that the name "Muscovites" for the population of Tsardom (Empire) of Russia is an error. During conversations they called themselves rusaki (which is a colloquial term for Russians) and only the citizens of the capital called themself "Muscovites". Margeret considered that this error is worse than calling all the French "Parisians."[9][10] Professor David Frick from the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute has also found in Vilnius the documents from 1655, which demonstrate that Moscovitae were also known in Lithuania as Rutheni.[11]

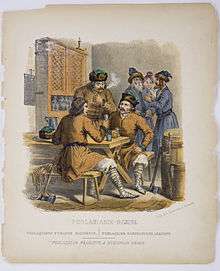

1, 2. Galician Ruthenians;

3. Carpathian Ruthenians;

4, 5. Podolian Ruthenians.

After the partition of Poland the term Ruthenian referred exclusively to people of the Rusyn- and Ukrainian-speaking areas of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, especially in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia.[3]

At the request of Mykhajlo Levitsky, in 1843 the term Ruthenian became the official name for the Rusyns and Ukrainians within the Austrian Empire.[3] For example, Ivan Franko and Stepan Bandera in their passports were identified as Ruthenians (Polish: Rusini).[12] By 1900 more and more Ruthenians began to call themselves with the self-designated name Ukrainians.[3] A number of Ukrainian members of the intelligentsia, such as Mykhailo Drahomanov and Ivan Franko, perceived the term as narrow-minded, provincial and Habsburg. With the emergence of Ukrainian nationalism during the mid-19th century, use of "Ruthenian" and cognate terms declined among Ukrainians, and fell out of use in Eastern and Central Ukraine. Most people in the western region of Ukraine followed suit later in the 19th century. During the early 20th century, the name Ukrajins’ka mova ("Ukrainian language") became accepted by much of the Ukrainian-speaking literary class in the Austro-Hungarian Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria.

Following the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, new states emerged and dissolved; borders changed frequently. After several years the Rusyn and Ukrainian speaking areas of eastern Austria-Hungary found themselves divided between the Ukrainian Soviet Republic, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Romania.

In the Soviet Union the Rusyns were not officially regarded as an ethnicity distinct from Ukrainians. However, the name Ruthenian (or "Little Ruthenian") was still often applied to the Rusyn minorities of Czechoslovakia and Poland.

The Polish census of 1931 listed "Russian", "Ruthenian" and "Ukrainian" (Polish: rossyjski, ruski, ukraiński, respectively) as separate languages.[13][14]

When commenting on the partition of Czechoslovakia by Nazi Germany in March 1939, US diplomat George Kennan noted, "To those who inquire whether these peasants are Russians or Ukrainians, there is only one answer. They are Neither. They are simply Ruthenians."[15] Dr. Paul R. Magosci emphasizes that modern Ruthenians have "the sense of a nationality distinct from Ukrainians" and often associate Ukrainians with Soviets or Communists.[16]

After the expansion of Soviet Ukraine following World War II, many groups who had not previously considered themselves Ukrainians were merged into the Ukrainian identity[17]

The government of Slovakia has proclaimed Rusyns (Rusíni) to be a distinct national minority (1991) and recognised Rusyn language as a distinct language (1995).[3]

Ruthenians in Poland

In the Interbellum period of the 20th century, the term rusyn (Ruthenian) was also applied to people from the Kresy Wschodnie (the eastern borderlands) in the Second Polish Republic, and included Ukrainians, Rusins, and Lemkos, or alternatively, members of the Uniate or Greek Catholic Church churches. In Galicia, the Polish government actively replaced all references to "Ukrainians" with the old word rusini ("Ruthenians"), an action that caused many Ukrainians to view their original self-designation with distaste.[18]

The Polish census of 1921 considered Ukrainians no other than Ruthenians.[19] However the Polish census of 1931 counted Belarusian, Ukrainian, Russian, and Ruthenian as separate language categories, and the census results were substantially different from before.[20] According to Rusyn-American historian Paul Robert Magocsi, Polish government policy in the 1930s pursued a strategy of tribalization, regarding various ethnographic groups—i.e., Lemkos, Boikos, and Hutsuls, as well Old Ruthenians and Russophiles—as different from other Ukrainians (although no such category existed in the Polish census apart from the first-language speakers of Russian[20]), and offered instructions in Lemko vernacular in state schools set up in the westernmost Lemko Region.[21]

Recognition of Rusyn people

The designations Rusyn and Carpatho-Rusyn were banned in the Soviet Union by the end of World War II in June 1945.[22] Ruthenians who identified under the Rusyn ethnonym and considered themselves to be a national and linguistic group separate from Ukrainians and Belarusians[16] were relegated to the Carpathian diaspora and formally functioned among the large immigrant communities in the United States.[22] A cross-European revival took place only with the collapse of communist rule in 1989.[22] This has resulted in political conflict and accusations of intrigue against Rusyn activists, including criminal charges. The Rusyn minority is well represented in Slovakia. The single category of people who listed their ethnicity as Rusyn was created in the 1920s, however, no generally accepted standardised Rusyn language existed.[23]

After World War II, following the practice in the Soviet Union, Ruthenian ethnicity was disallowed. This Soviet policy maintained that the Ruthenians and their language were part of the Ukrainian ethnic group and language. At the same time, the Greek Catholic church was banned and replaced with the Eastern Orthodox church under the Russian Patriarch, in an atmosphere which repressed all religions. Thus, in Slovakia the former Ruthenians were technically free to register as any ethnicity but Ruthenian.[23]

See also

- American Carpatho-Ruthenian Orthodox Diocese

- Coat of arms of Carpathian Ruthenia

- Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth

- Ruthenian Greek Catholic Church

- Ruthenian nobility

- Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

- Ukrainian Russophiles

Citations

- Litauen und Ruthenien : Studien zu einer transkulturellen Kommunikationsregion (15.-18. Jahrhundert) = Lithuania and Ruthenia : studies of a transcultural communication zone (15th-18th centuries). Rohdewald, Stefan., Frick, David A., Wiederkehr, Stefan. Wiesbaden. 2007. p. 22. ISBN 9783447056052. OCLC 173071153.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "History of St. Josaphat Ukrainian Catholic Church Bethlehem". St. Josaphat Bethlehem. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- Himka, John-Paul. "Ruthenians". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com. Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine.

- Statute of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (1529), Part. 1., Art. 1.: "На первей преречоным прелатом, княжатом, паном, хоруговым, шляхтам и местом преречоных земель Великого князства Литовского, Руского, Жомойтского и иных дали есмо:..."; According to.: Pervyi ili Staryi Litovskii Statut // Vremennik Obschestva istorii i drevnostei Rossiiskih. 1854. Book 18. p. 2-106. P. 2.

- Miroliubov, Yuri (2015). Образование Киевской Руси и ее государственности (Времена до князя Кия и после него) [The formation of Kievan Rus' and its statehood (from the time of Prince Kyi and after him)] (in Russian). Direct Media. p. 27. ISBN 978-5-4475-3900-9. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- Sigismund von Herberstein Rerum Moscoviticarum Commentarii

- Myl'nikov 1999, p. 46.

- Лобин А. Н. Послание государя Василия III Ивановича императору Карлу V от 26 июня 1522 г.: Опыт реконструкции текста // Studia Slavica et Balcanica Petropolitana, № 1. Санкт-Петербург, 2013. C. 131.

- Dunning, Chester (15 June 1983). The Russian Empire and Grand Duchy of Muscovy: A Seventeenth-Century French Account. University of Pittsburgh Pre. pp. 7, 106. ISBN 978-0-8229-7701-8.

- Myl'nikov 1999, p. 84.

- Frick D. Ruthenians and their language in Seventeenth-century Vilnius, in: Speculum Slaviae Orientalis, IV. pp. 44-65.

- (in Russian) Panayir, D. Muscophillia. How Galicians taught Russians to love Russia (Москвофільство. Як галичани вчили росіян любити Росію). Istorychna Pravda (Ukrayinska Pravda). 16 February 2011

- Henryk Zieliński, Historia Polski 1914-1939, (1983) Wrocław: Ossolineum

- "Główny Urząd Statystyczny Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, drugi powszechny spis ludności z dn. 9.XII 1931 r. - Mieszkania i gospodarstwa domowe ludność" [Central Statistical Office the Polish Republic, the second census dated 9.XII 1931 - Abodes and household populace] (PDF) (in Polish). Central Statistical office of the Polish Republic. 1938. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2014.

- Report on Conditions in Ruthenia March 1939, From Prague After Munich: Diplomatic Papers 1938-1940, (Princeton University Press, 1968)

- Paul R. Magosci, "The Rusyn Question" Political Thought 1995, №2-3 (6) P.221-231, :http://www.litopys.org.ua/rizne/magocie.htm

- "Ruthenian: also called Rusyn, Carpatho-Rusyn, Lemko, or Rusnak". Status since the end of World War II. Encyclopædia Britannica.

Subcarpathian Rus was ceded by Czechoslovakia to the Soviet Union and became the Transcarpathian oblast (region) of the Ukrainian S.S.R. The designations Rusyn and Carpatho-Rusyn were banned, and the local East Slavic inhabitants and their language were declared to be Ukrainian. Soviet policy was followed in neighbouring communist Czechoslovakia and Poland, where the Carpatho-Rusyn inhabitants (Lemko Rusyns in the case of Poland) were henceforth officially designated Ukrainians

- Magocsi, Paul R. (1996). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples. University of Toronto Press (published 2010). p. 638. ISBN 9781442610217. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

[...] the Polish government never referred to the Ukrainians and their language by the modern name Ukrainian; instead, it used the historical name Rusyn (Polish: Rusin), thereby inadvertently contributing to a disliking on the part of many Ukrainians, especially Galician Ukrainians, for their original national designation.

- (Polish) Główny Urząd Statystyczny (corporate author) (1932) "Ludnosc, Ludnosc wedlug wyznania religijnego i narodowosci" (table 11, pg. 56

- (Polish) Główny Urząd Statystyczny (corporate author) (1932) "Ludnosc. Ludnosc wedlug wyznania i plci oraz jezyka ojczystego" (table 10, pg. 15).

- Magocsi, Paul R. (1996). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples. University of Toronto Press (published 2010). p. 638. ISBN 9781442610217. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- "Ruthenian: also called Rusyn, Carpatho-Rusyn, Lemko, or Rusnak". Status since the end of World War II. Encyclopædia Britannica.

Today the name Rusyn refers to the spoken language and variants of a literary language codified in the 20th century for Carpatho-Rusyns living in Ukraine (Transcarpathia), Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, and Serbia (the Vojvodina).

- Christina Bratt Paulston, Donald Peckham (1998). Linguistic Minorities in Central and Eastern Europe. Soviet Heritage: Ruthenians. Multilingual Matters. pp. 258–259. ISBN 1853594164. Retrieved 8 October 2015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

General ources

- Myl'nikov, Alexander (1999). The Picture of the Slavic World: The View from the Eastern Europe: Views of Ethnic Names and Ethnicity (XVIth–beginning of the XVIIIth century). St. Petersburg: Петербургское востоковедение. ISBN 5-85803-117-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Nakonechny, Ye. УКРАДЕНЕ ІМ’Я чому русини стали українцями [Stolen Name: Why Ruthenians Became Ukrainians] (in Ukrainian). Stefanyk Science Library (National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine). Lviv, 2001.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ruthenians. |

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Himka, John-Paul. "Ruthenians". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com. Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine.

- Carpatho-Rusyn Heritage - The Carpathian Connection