Ruby-throated hummingbird

The ruby-throated hummingbird (Archilochus colubris) is a species of hummingbird that generally spends the winter in Central America, Mexico, and Florida, and migrates to Eastern North America for the summer to breed. It is by far the most common hummingbird seen east of the Mississippi River in North America.

| Ruby-throated hummingbird | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Apodiformes |

| Family: | Trochilidae |

| Genus: | Archilochus |

| Species: | A. colubris |

| Binomial name | |

| Archilochus colubris | |

| |

| Summer-only range Winter-only range Migratory path | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Trochilus colubris Linnaeus, 1758 | |

Description

This hummingbird is from 7 to 9 cm (2.8 to 3.5 in) long and has an 8 to 11 cm (3.1 to 4.3 in) wingspan. Weight can range from 2 to 6 g (0.071 to 0.212 oz), with males averaging 3.4 g (0.12 oz) against the slightly larger female which averages 3.8 g (0.13 oz).[2][3] Adults are metallic green above and grayish white below, with near-black wings. Their bill, at up to 2 cm (0.79 in), is long, straight, and very slender. As in all hummingbirds, the toes and feet of this species are quite small, with a middle toe of around 0.6 cm (0.24 in) and a tarsus of approximately 0.4 cm (0.16 in). The ruby-throated hummingbird can only shuffle if it wants to move along a branch, though it can scratch its head and neck with its feet.[4][5]

The species is sexually dimorphic.[6] The adult male has a gorget (throat patch) of iridescent ruby red bordered narrowly with velvety black on the upper margin and a forked black tail with a faint violet sheen. The red iridescence is highly directional and appears dull black from many angles. The female has a notched tail with outer feathers banded in green, black, and white and a white throat that may be plain or lightly marked with dusky streaks or stipples. Males are smaller than females and have slightly shorter bills. Juvenile males resemble adult females, though usually with heavier throat markings.[7] The plumage is molted once a year on the wintering grounds, beginning in early fall and ending by late winter.[8]

Habitat, range and migration

The breeding habitat is throughout most of the Eastern United States and south-central and southeastern Canada in deciduous and pine forests and forest edges, orchards, and gardens. The female builds a nest in a protected location in a shrub or a tree. Of all hummingbirds in the United States, this species has the largest breeding range.[4]

The ruby-throated hummingbird is migratory, spending most of the winter in Florida, southern Mexico and Central America,[9] as far south as extreme western Panama,[10] and the West Indies. During migration, some birds embark on a nonstop 900-mile journey across the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean from Panama or Mexico to the eastern United States.[9] The bird breeds throughout the eastern United States, east of the 100th meridian, and in southern Canada, particularly Ontario, in eastern and mixed deciduous and broadleaved forest.[11][12] In winter, it is seen mostly in Mexico and Florida.

During migration southward in autumn along the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico, older male and female birds were better prepared for long-distance flight than first-year birds by having higher body weights and larger fuel loads.[13]

Behavior and metabolism

Ruby-throated hummingbirds are solitary. Adults of this species are not social, other than during courtship (which lasts a few minutes); the female also cares for her offspring. Both males and females of any age are aggressive toward other hummingbirds. They may defend territories, such as a feeding territory, attacking and chasing other hummingbirds that enter.

As part of their spring migration, portions of the population fly from the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico across the Gulf of Mexico, arriving first in Florida and Louisiana.[9] This feat is impressive, as an 800 km (500 mi), non-stop flight over water would seemingly require a caloric energy that far exceeds an adult hummingbird's body weight of 3 g (0.11 oz).[9] However, researchers discovered the tiny birds can double their fat mass in preparation for their Gulf crossing,[14] then expend the entire calorie reserve from fat during the 20-hour non-stop crossing when food and water are unavailable.[9][14]

Hummingbirds have one of the highest metabolic rates of any animal, with heart rates up to 1260 beats per minute, breathing rate of about 250 breaths per minute even at rest, and oxygen consumption of about 4 ml oxygen/g/hour at rest.[15] During flight, hummingbird oxygen consumption per gram of muscle tissue is approximately 10 times higher than that seen for elite human athletes.[9]

They feed frequently while active during the day. When temperatures drop, particularly on cold nights, they may conserve energy by entering hypothermic torpor.[9]

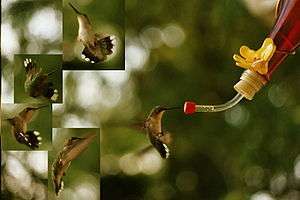

Flight

Hummingbirds have many skeletal and flight muscle adaptations which allow great agility in flight. Muscles make up 25–30% of their body weight, and they have long, blade-like wings that, unlike the wings of other birds, connect to the body only from the shoulder joint.[16] This adaptation allows the wing to rotate almost 180°, enabling the bird to fly not only forward but backward, and to hover in mid-air, flight capabilities that are similar to insects and unique among birds.[16]

The main wing bone, the humerus, is specifically adapted for hovering flight. Hummingbirds have a relatively short humerus with proportionally massive deltoid-pectoral muscles which permit pronounced wing supination during upstroke when hovering.[17]

A hummingbird's ability to hover is due to its small mass, high wingbeat frequency and relatively large margin of mass-specific power available for flight. Several anatomical features contribute further, including proportionally massive major flight muscles (pectoralis major and supracoracoideus) and wing anatomy that enables the bird to leave its wings extended yet turned over (supine) during the upstroke. This generates lift that supports body weight and maneuvering.[18]

Hummingbirds achieve ability to support their weight and hover from wing beats creating lift on the downstroke of a wing flap and also on the upstroke in a ratio of 75%:25%, respectively, similarly to an insect.[18][19] Hummingbirds and insects gain lift during hovering partially through inversion of their cambered wings during an upstroke.[19] During hovering, hummingbird wings beat up to 80 times per second.[20]

Diet

.jpg)

Nectar from flowers and flowering trees, as well as small insects and spiders, are its main food. Although hummingbirds are well known to feed on nectar, small arthropods are an important source part of protein, minerals, and vitamins in the diet of adult hummingbirds. Hummingbirds show a slight preference for red, orange, and bright pink tubular flowers as nectar sources, though flowers not adapted to hummingbird pollination (e.g., willow catkins) are also visited.[10] Their diet may also occasionally include sugar-rich tree sap taken from sapsucker wells. The birds feed from flowers using a long, extendable tongue and catch insects on the wing or glean them from flowers, leaves, bark, and spiders' webs.

Young birds are fed insects for protein since nectar is an insufficient source of protein for the growing birds.[10]

Reproduction

As typical for their family, ruby-throated hummingbirds are thought to be polygynous. Polyandry and polygynandry may also occur. They do not form breeding pairs, with males departing immediately after the reproductive act and females providing all parental care.[21]

Males arrive at the breeding area in the spring and establish a territory before the females arrive. When the females return, males court females that enter their territory by performing courtship displays. They perform a "dive display" rising 2.45–3.1 m (8.0–10.2 ft) above and 1.52–1.82 m (5.0–6.0 ft) to each side of the female. If the female perches, the male begins flying in very rapid horizontal arcs less than 0.5 m (1.6 ft) in front of her. If the female is receptive to the male, she may give a call and assume a solicitous posture with her tail feathers cocked and her wings drooped.

The nest is usually constructed on a small, downward-sloping tree limb 3.1 to 12.2 m (10 to 40 ft) feet above the ground. Favored trees are usually deciduous, such as oak, hornbeam, birch, poplar or hackberry, although pines have also been used. Nests have even been found on loops of chain, wire, and extension cords.[4] The nest is composed of bud scales, with lichen on the exterior, bound with spider's silk, and lined with fibers such as plant down (often dandelion or thistle down) and animal hair. Most nests are well camouflaged. Old nests may be occupied for several seasons, but are repaired annually.[10] As in all known hummingbird species, the female alone constructs the nest and cares for the eggs and young.

Females lay two (with a range of 1 to 3) white eggs about 12.9 mm × 8.5 mm (0.51 in × 0.33 in) in size and produce one to two broods each summer.[4] They brood the chicks over a period of 12 to 14 days, by which point they are feathered and homeothermic. The female feeds the chicks from 1 to 3 times every hour by regurgitation, usually while the female continues hovering. When they are 18 to 22 days old, the young leave the nest and make their first flight.[10]

Longevity and mortality

The oldest known ruby-throated hummingbird to be banded was 9 years and 1 month of age. Almost all hummingbirds of 7 years or more in age are females, with males rarely surviving past 5 years of age. Reasons for higher mortality in males may include loss of weight during the breeding season due to the high energetic demands of defending a territory followed by energetically costly migration.[9]

A variety of animals prey on hummingbirds given the opportunity. Due to their small size, hummingbirds are vulnerable even to passerine birds and other animals which generally feed on insects. On the other hand, only very swift predators can capture them and a free-flying adult hummingbird is too nimble for most predators. Chief among their predators are the smaller, swifter raptors like sharp-shinned hawks, merlins, American kestrels and Mississippi kites as well as domestic cats, loggerhead shrikes and even greater roadrunners, all of which are likely to ambush the hummingbird while it sits or sleeps on a perch or are distracted by breeding or foraging activities. Predatory lizards and bird-eating snakes may also prey on the species, especially on its tropical wintering grounds. Even large, predatory invertebrates have preyed on ruby-throated hummingbirds, including praying mantises (which have been seen to ambush adult hummingbirds at hummingbird feeders on more than one occasion), orb-weaver spiders, and green Darners. Blue jays are common predators of nests, as are several other corvids in addition to some icterids, bats, squirrels and chipmunks.[22][23][24][25]

Vocalization

The vocalizations of ruby-throated hummingbirds are rapid, squeaky chirps, which are used primarily for threats. For example, males may vocalize to warn another male that has entered his territory.

During the courtship displays, the male makes a rapid tik-tik tik-tik tik-tik sound with his wings.[26] The sound is produced both during the shuttle display, at each end of the side-to-side flight. Also, the sound is made during dive displays. A second, rather faint, repeated whining sound is sometimes produced with the outer tail-feathers during the dive, as the male flies over the female, spreading and shutting the tail as he does so.

Gallery

.jpg) Male ruby-throated hummingbird guarding his territory from the top of a tomato stake

Male ruby-throated hummingbird guarding his territory from the top of a tomato stake Brooklyn Museum - Ruby-throated Humming Bird - John J. Audubon

Brooklyn Museum - Ruby-throated Humming Bird - John J. Audubon_RWD4.jpg) Female ruby-throated hummingbird, North Carolina

Female ruby-throated hummingbird, North Carolina Male ruby-throated hummingbird perched on a branch, displaying its tongue, East Texas

Male ruby-throated hummingbird perched on a branch, displaying its tongue, East Texas

Other reading

- Robinson, T. R., R. R. Sargent, and M. B. Sargent (1996). Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris). In The Birds of North America. No. 204 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

- Williamson, S. L. (2001). A Field Guide to Hummingbirds of North America (Peterson Field Guide Series). Houghton Mifflin. Co., Boston, MA.

- Ruby-throated hummingbird information

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Archilochus colubris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kirschbaum, Kari. "ADW: Archilochus colubris: INFORMATION". Animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- "Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Life History, All About Birds – Cornell Lab of Ornithology". Allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- "Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Life History, All About Birds – Cornell Lab of Ornithology". Allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- "John James Audubon's Description of the Ruby-throated Hummingbird". Rubythroat.org. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- "Hummingbird: external appearance, ageing, sexing". Ruby-Throat.org. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- Williamson (2001)

- Baltosser, William H. (1995). "Annual Molt in Ruby-throated and Black-chinned Hummingbirds" (PDF). The Condor. 97 (2): 484–491. doi:10.2307/1369034. JSTOR 1369034 – via Searchable Ornithological Research Archive.

- Hargrove, J. L. (2005). "Adipose energy stores, physical work, and the metabolic syndrome: Lessons from hummingbirds". Nutrition Journal. 4: 36. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-4-36. PMC 1325055. PMID 16351726.

- Robinson et al. (1996)

- Harris, M.; Naumann, R.; Kirschbaum, K. "Archilochus colubris". University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 24 August 2007.

- "The Ontario hummingbird project: migration and range maps". The Ontario Hummingbird Project. 2013. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Zenzal, T.J. and F.R. Moore (2016). "Stopover biology of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris) during autumn migration". The Auk: Ornithological Advances. 133 (2): 237–250. doi:10.1642/AUK-15-160.1.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Zenzal, T.J. and F.R. Moore. 2016. Stopover biology of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris) during autumn migration. The Auk: Ornithological Advances 133: 237–250.

- Suarez, R. K. (1992). "Hummingbird flight: Sustaining the highest mass-specific metabolic rates among vertebrates". Experientia. 48 (6): 565–70. doi:10.1007/bf01920240. PMID 1612136.

- Hedrick, T. L.; Tobalske, B. W.; Ros, I. G.; Warrick, D. R.; Biewener, A. A. (2011). "Morphological and kinematic basis of the hummingbird flight stroke: scaling of flight muscle transmission ratio". Proc Biol Sci. 22279 (1735): 1986–1992. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.2238. PMC 3311889. PMID 22171086.

- Tobalske, B. W.; Biewener, A. A.; Warrick, D. R.; Hedrick, T. L.; Powers, D. R. (2010). "Effects of flight speed upon muscle activity in hummingbirds" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 213 (Pt 14): 2515–23. doi:10.1242/jeb.043844. PMID 20581281.

- Tobalske BW (2010). "Hovering and intermittent flight in birds". Bioinspir Biomim. 5 (4): 045004. doi:10.1088/1748-3182/5/4/045004. PMID 21098953.

- Warrick DR, Tobalske BW, Powers DR (2005). "Aerodynamics of the hovering hummingbird". Nature. 435 (23 June 7045): 1094–7. doi:10.1038/nature03647. PMID 15973407.

- Gill V (30 July 2014). "Hummingbirds edge out helicopters in hover contest". BBC News. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- Lanny Chambers. "Ruby-throated Hummingbird". Hummingbirds.net. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- Kirschbaum, Kari. "ADW: Archilochus colubris: INFORMATION". Animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- "Hummingbirds: Predators 1". Rubythroat.org. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- "Praying Mantis Makes Meal of a Hummingbird | Bird Watcher's Digest". Birdwatchersdigest.com. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- Weidensaul, Scott, T. R. Robinson, R. R. Sargent and M. B. Sargent. 2013. Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- Clark, C. J.; Elias, D. O.; Prum, R. O. (2011). "Aeroelastic flutter produces hummingbird feather songs" (PDF). Science. 333 (6048): 1430–3. doi:10.1126/science.1205222. PMID 21903810.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikispecies has information related to Archilochus colubris |

- Tracking Migration/Journey North

- Ruby-throated hummingbird nest images (day-by-day)

- Ruby-throated hummingbird nest cycle

- Ruby-throated hummingbird species account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Ruby-throated hummingbird – Archilochus colubris – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Operation rubythroat: The Hummingbird Project

- All about the ruby-throated hummingbird

- How to Photograph Hummingbirds – including many photos of this species

- Migration map (US and Canada only)

- 2007 spring migration

- Ruby-throated hummingbird stamps at bird-stamps.org

- "Ruby-throated hummingbird media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Videos of ruby-throated hummingbirds

- Research project on the ruby-throated hummingbird in Québec

- Ruby-throated Hummingbird Migration Map Archives (2002–present)

- Ruby-throated hummingbird photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)