Roman–Seleucid War

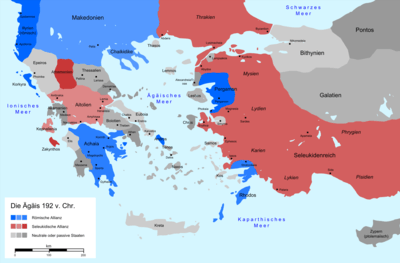

The Seleucid War (192–188 BC), also known as the War of Antiochos or the Syrian War, was a military conflict between two coalitions led by the Roman Republic and the Seleucid Empire. The fighting took place in modern day southern Greece, the Aegean Sea and Asia Minor.

| Seleucid War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Macedonian Wars | |||||||||

Map of Asia Minor and the general region after the war | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Seleucid Empire Aetolian League Athamania Kingdom of Cappadocia |

Achaean League Pergamon Rhodes | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Antiochus III the Great Hannibal Polyxenidas |

Lucius Aemilius Regillus Scipio Asiaticus Scipio Africanus Eumenes II of Pergamum Philip V of Macedon | ||||||||

The war was the consequence of a "cold war" between both powers, which had started in 196 BC. In this period Romans and Seleucids had tried to settle spheres of influence by making alliances with the small Greek city states.

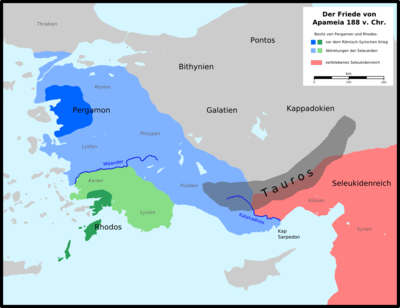

The fighting ended with a clear Roman victory. In the Treaty of Apamea the Seleucids were forced to give up Asia Minor, which fell to Roman allies. As a main result of the war the Roman Republic gained hegemony over Greek city states and Asia Minor, and became the only remaining major power around the Mediterranean Sea.

Prelude

Antiochus III the Great, the Seleucid king, first became involved with Greece when he signed an alliance with King Philip V of Macedon in 203 BC.[1] The treaty stated that Antiochus and Philip would help each other conquer the lands of the young Ptolemaic pharaoh, Ptolemy V.[1]

In 200 BC, Rome first became involved in the affairs of Greece, when two of its allies, Pergamum and Rhodes, who had been fighting Philip in the Cretan War, appealed to the Romans for help.[2] In response to this appeal the Romans sent an army to Greece and attacked Macedon. The Second Macedonian War lasted until 196 BC, and it effectively ended when the Romans and their allies, including the Aetolian League, defeated Philip at the Battle of Cynoscephalae. The treaty's terms forced Philip to pay a war indemnity and become a Roman ally while Rome occupied some areas of Greece.

Meanwhile, Antiochus was fighting the armies of Ptolemy in Coele-Syria in the Fifth Syrian War (201–195 BC). Antiochus' army crushed the Egyptian army at the Battle of Panium in 201 BC, and by 198 BC, Coele-Syria was in Antiochus' hands.

Antiochus then concentrated on raiding Ptolemaic possessions in Cilicia, Lycia and Caria.[3] While attacking Ptolemy's possessions in Asia Minor, Antiochus sent a fleet to occupy Ptolemy's coastal cities in the area as well as to support Philip.[3] Rhodes, a Roman ally and the strongest naval power in the area became alarmed and sent envoys to Antiochus saying that they would have to oppose him if his fleet passed Chelidonae in Cilicia because they didn't want Philip to receive aid.[4] Antiochus ignored the threat and kept proceeding with his naval movements, but the Rhodians did not act because they had heard that Philip had been defeated at Cynoscephalae and was no longer a threat.[4]

Peace was established in 195 BC with the marriage of Antiochus' daughter, Cleopatra, to Ptolemy. Antiochus' hands were now clear of problems in Asia and he now turned his eyes towards Europe.

Outbreak of the war

Meanwhile, Hannibal, the Carthaginian general who had fought against Rome in the Second Punic War, fled from Carthage to Tyre, and from there he sought refuge at Antiochus' court in Ephesus where the King was deciding what actions to take against Rome.[5]

Because of the continued Roman influence in Greece, the Aetolians, in spite of the philo-Hellenic consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus having just declared Greece "free", now garrisoned Chalcis and Demetrias, which the Romans themselves had argued were key to Macedonia's domination of Greece, and became anti-Roman. They also resented how the Romans had prevented them from reincorporating Echinus and Pharsalus, which had formerly been part of the League, at the end of the Second Macedonian War.[6] In 195 BC, when the Romans decided to invade Sparta, the Aetolians, wanting the Romans to leave Greece, offered to deal with Sparta. However, the Achaean League, not wanting Aetolia's power to grow, refused.[7] The modern historian Erich Gruen has suggested that the Romans may have used the war as an excuse to station a few legions in Greece in order to prevent the Spartans and the Aetolian League from joining the Seleucid King Antiochus III if he invaded Greece.[8]

Having defeated Sparta in 195 BC, the Roman legions under Flamininus left Greece the next year. In 192 BC, a weakened Sparta appealed to the Aetolians for military assistance.[9] The Aetolians responded to this request by sending a unit of 1,000 cavalry.[10] However, after they got there, this force assassinated Nabis, Sparta's last independent ruler, and tried to gain control of Sparta, only to be defeated.[10]

The military conflict

Building on anti-Roman sentiment in Greece, particularly among the city-states of the Aetolian League, Antiochus III led an army across the Hellespont planning to "liberate" it. Antiochus and the Aetolian league failed to gain the support of Philip V of Macedon and the Achaean League. The Romans responded to the invasion by sending an army to Greece which defeated Antiochus' army at Thermopylae.

This defeat proved crushing, and Antiochus was forced to retreat from Greece. The Romans under the command of Scipio Asiaticus followed him across the Aegean. The combined Roman-Rhodian fleet defeated the Seleucid fleet commanded by Hannibal at the Battle of the Eurymedon and at the Battle of Myonessus. After some fighting in Asia Minor, the Seleucids fought against the armies of Rome and Pergamum at Magnesia. The Roman-Pergamese army won the battle, and Antiochus was forced to retreat.

The Peace of Apamea

The battle was disastrous for the Seleucids, and Antiochus was forced to come to terms. Amongst the terms of the Treaty of Apamea, Antiochus had to pay 15,000 talents (450 tonnes/990,000 pounds) of silver as a war indemnity, and he was forced to abandon his territory west and north of the Taurus Mountains. Rhodes gained control over Caria and Lycia, while the Pergamese gained northern Lycia and all of Antiochus' other territories in Asia Minor.

See also

References

Bibliography

Ancient literature

Modern literature

- Ernst Badian, (1959). Rome and Antiochos the Great: A Study in Cold War. CPh 54, Page 81–99.

- John D. Grainger, (2002). The Roman War of Antiochos the Great. Leiden and Boston.

- Peter Green, (1990). Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age, (2nd edition). Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-500-01485-X.

- Erich Gruen, (1984). The Hellenistic World and the Coming of Rome. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05737-6

- Bezalel Bar-Kochva, (1976). The Seleucid Army. Organization and Tactics in the Great Campaigns. Cambridge.

- Robert M. Errington, (1989). Rome against Philipp and Antiochos. In: A.E. Astin (Hrsg.). CAH VIII2, S. 244–289.

| Library resources about Roman-Seleucid War |

Further reading

- Sherwin-White, Adrian N. 1984. Roman foreign policy in the East 168 B.C. to A.D. 1. London: Duckworth.

- Sullivan, Richard D. 1990. Near Eastern royalty and Rome: 100–30 B.C. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.