Retail

Retail is the process of selling consumer goods or services to customers through multiple channels of distribution to earn a profit. Retailers satisfy demand identified through a supply chain. The term "retailer" is typically applied where a service provider fills the small orders of many individuals, who are end-users, rather than large orders of a small number of wholesale, corporate or government clientele. Shopping generally refers to the act of buying products. Sometimes this is done to obtain final goods, including necessities such as food and clothing; sometimes it takes place as a recreational activity. Recreational shopping often involves window shopping and browsing: it does not always result in a purchase.

.jpg)

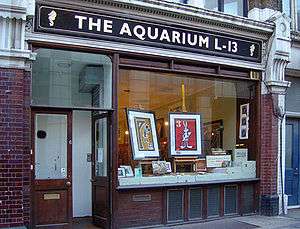

Retail markets and shops have a very ancient history, dating back to antiquity. Some of the earliest retailers were itinerant peddlers. Over the centuries, retail shops were transformed from little more than "rude booths" to the sophisticated shopping malls of the modern era.

Most modern retailers typically make a variety of strategic level decisions including the type of store, the market to be served, the optimal product assortment, customer service, supporting services and the store's overall market positioning. Once the strategic retail plan is in place, retailers devise the retail mix which includes product, price, place, promotion, personnel, and presentation. In the digital age, an increasing number of retailers are seeking to reach broader markets by selling through multiple channels, including both bricks and mortar and online retailing. Digital technologies are also changing the way that consumers pay for goods and services. Retailing support services may also include the provision of credit, delivery services, advisory services, stylist services and a range of other supporting services.

Retail shops occur in a diverse range of types and in many different contexts – from strip shopping centres in residential streets through to large, indoor shopping malls. Shopping streets may restrict traffic to pedestrians only. Sometimes a shopping street has a partial or full roof to create a more comfortable shopping environment – protecting customers from various types of weather conditions such as extreme temperatures, winds or precipitation. Forms of non-shop retailing include online retailing (a type of electronic-commerce used for business-to-consumer (B2C) transactions) and mail order.

Etymology

The word retail comes from the Old French verb tailler, meaning "to cut off, clip, pare, divide in terms of tailoring" (c. 1365). It was first recorded as a noun in 1433 with the meaning of "a sale in small quantities" from the Middle French verb retailler meaning "a piece cut off, shred, scrap, paring".[1] At the present, the meaning of the word retail (in English, French, Dutch, and German) refers to the sale of small quantities of items to consumers (as opposed to wholesale).

Definition and explanation

Retail refers to the activity of selling goods or services directly to consumers or end-users.[2] Some retailers may sell to business customers, and such sales are termed non-retail activity. In some jurisdictions or regions, legal definitions of retail specify that at least 80 percent of sales activity must be to end-users.[3]

Retailing often occurs in retail stores or service establishments, but may also occur through direct selling such as through vending machines, door-to-door sales or electronic channels.[4] Although the idea of retail is often associated with the purchase of goods, the term may be applied to service-providers that sell to consumers. Retail service providers include retail banking, tourism, insurance, private healthcare, private education, private security firms, legal firms, publishers, public transport and others. For example, a tourism provider might have a retail division that books travel and accommodation for consumers plus a wholesale division that purchases blocks of accommodation, hospitality, transport and sightseeing which are subsequently packaged into a holiday tour for sale to retail travel agents.

Some retailers badge their stores as "wholesale outlets" offering "wholesale prices." While this practice may encourage consumers to imagine that they have access to lower prices, while being prepared to trade-off reduced prices for cramped in-store environments, in a strictly legal sense, a store that sells the majority of its merchandise direct to consumers, is defined as a retailer rather than a wholesaler. Different jurisdictions set parameters for the ratio of consumer to business sales that define a retail business.

History

- See also: History of merchants; History of the market place ; History of marketing

Retailing in antiquity

Retail markets have existed since ancient times. Archaeological evidence for trade, probably involving barter systems, dates back more than 10,000 years. As civilizations grew, barter was replaced with retail trade involving coinage. Selling and buying are thought to have emerged in Asia Minor (modern Turkey) in around the 7th-millennium BCE.[5] Gharipour points to evidence of primitive shops and trade centers in Sialk Hills in Kashan (6000 BCE), Catalk Huyuk in modern-day Turkey (7,500–5,700 BCE), Jericho (2600 BCE) and Susa (4000 BCE).[6] Open air, public markets were known in ancient Babylonia, Assyria, Phoenicia, and Egypt. These markets typically occupied a place in the town's center. Surrounding the market, skilled artisans, such as metal-workers and leather workers, occupied permanent premises in alleys that led to the open market-place. These artisans may have sold wares directly from their premises, but also prepared goods for sale on market days.[7] In ancient Greece markets operated within the agora, an open space where, on market days, goods were displayed on mats or temporary stalls.[8] In ancient Rome, trade took place in the forum.[9] Rome had two forums; the Forum Romanum and Trajan's Forum. The latter was a vast expanse, comprising multiple buildings with shops on four levels.[10] The Roman forum was arguably the earliest example of a permanent retail shop-front.[11] In antiquity, exchange involved direct selling via merchants or peddlers and bartering systems were commonplace.[12]

The Phoenicians, noted for their seafaring skills, plied their ships across the Mediterranean, becoming a major trading power by the 9th century BCE. The Phoenicians imported and exported wood, textiles, glass and produce such as wine, oil, dried fruit, and nuts. Their trading skills necessitated a network of colonies along the Mediterranean coast, stretching from modern-day Crete through to Tangiers and onto Sardinia[13] The Phoenicians not only traded in tangible goods, but were also instrumental in transporting culture. The Phoenician's extensive trade networks necessitated considerable book-keeping and correspondence. In around 1500 BCE, the Phoenicians developed a consonantal alphabet which was much easier to learn that the complex scripts used in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Phoenician traders and merchants were largely responsible for spreading their alphabet around the region.[14] Phoenician inscriptions have been found in archaeological sites at a number of former Phoenician cities and colonies around the Mediterranean, such as Byblos (in present-day Lebanon) and Carthage in North Africa.[15]

In the Graeco-Roman world, the market primarily served the local peasantry. Local producers, who were generally poor, would sell small surpluses from their individual farming activities, purchase minor farm equipment and also buy a few luxuries for their homes. Major producers such as the great estates were sufficiently attractive for merchants to call directly at their farm-gates, obviating the producers' need to attend local markets. The very wealthy landowners managed their own distribution, which may have involved exporting and importing. The nature of export markets in antiquity is well documented in ancient sources and archaeological case studies.[16] The Romans preferred to purchase goods from specific places: oysters from Londinium, cinnamon from a specific mountain in Arabia, and these place-based preferences stimulated trade throughout Europe and the Middle East.[17] Markets were also important centers of social life.[18]

The rise of retailing and marketing in England and Europe has been extensively studied, but less is known about developments elsewhere.[19] Nevertheless, recent research suggests that China exhibited a rich history of early retail systems.[20] From as early as 200 BCE, Chinese packaging and branding were used to signal family, place names and product quality, and the use of government imposed product branding was used between 600 and 900 CE.[21] Eckhart and Bengtsson have argued that during the Song Dynasty (960–1127), Chinese society developed a consumerist culture, where a high level of consumption was attainable for a wide variety of ordinary consumers rather than just the elite.[22] The rise of a consumer culture led to the commercial investment in carefully managed company image, retail signage, symbolic brands, trademark protection and sophisticated brand concepts.[23]

Retailing in Medieval Europe

In Medieval England and Europe, relatively few permanent shops were to be found; instead, customers walked into the tradesman's workshops where they discussed purchasing options directly with tradesmen. In 13th-century London, mercers, and haberdashers were known to exist and grocers sold "miscellaneous small wares as well as spices and medicines" but fish and other perishables were sold through markets, costermongers, hucksters, peddlers or other types of itinerant vendor.[24]

In the more populous cities, a small number of shops were beginning to emerge by the 13th century. In Chester, a medieval covered shopping arcade represented a major innovation that attracted shoppers from many miles around. Known as "The Rows" this medieval shopping arcade is believed to be the first of its kind in Europe.[25] Fragments of Chester's Medieval Row, which is believed to date to the mid-13th century, can still be found in Cheshire.[26] In the 13th or 14th century, another arcade with several shops was recorded at Drapery Row in Winchester.[27] The emergence of street names such as Drapery Row, Mercer's Lane and Ironmonger Lane in the medieval period suggests that permanent shops were becoming more commonplace.

Medieval shops had little in common with their modern equivalent. As late as the 16th century, London's shops were described as little more than "rude booths" and their owners "bawled as loudly as the itinerants."[28] Shopfronts typically had a front door with two wider openings on either side, each covered with shutters. The shutters were designed to open so that the top portion formed a canopy while the bottom was fitted with legs so that it could serve as a shopboard.[29] Cox and Dannehl suggest that the Medieval shopper's experience was very different. The lack of glazed windows, which were rare during the medieval period, and did not become commonplace until the eighteenth century, meant that shop interiors were dark places. Outside the markets, goods were rarely out on display and the service counter was unknown. Shoppers had relatively few opportunities to inspect the merchandise prior to consumption. Many stores had openings onto the street from which they served customers.[30]

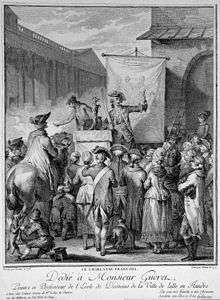

Outside the major cities, most consumable purchases were made through markets or fairs. Markets were held daily in the more populous towns and cities or weekly in the more sparsely populated rural districts. Markets sold fresh produce; fruit, vegetables, baked goods, meat, poultry, fish and some ready to eat foodstuffs; while fairs operated on a periodic cycle and were almost always associated with a religious festival.[31] Fairs sold non-perishables such as farm tools, homewares, furniture, rugs and ceramics. Market towns dotted the medieval European landscape while itinerant vendors supplied less populated areas or hard-to-reach districts. Peddlers and other itinerant vendors operated alongside other types of retail for centuries. The political philosopher, John Stuart Mill compared the convenience of markets/fairs to that of the itinerant peddlers:

- "The contrivance of fairs and markets was early had recourse to, where consumers and producers might periodically meet, without any intermediate agency; and this plan answers tolerably well for many articles, especially agricultural produce … but were inconvenient to buyers who have other occupations, and do not live in the immediate vicinity … and the wants of the consumers must either be provided for so long beforehand, or must remain so long unsupplied, that even before the resources of society admitted of the establishment of shops, the supply of these wants fell universally into the hands of itinerant dealers: the pedlar, who might appear once a month, being preferred to the fair, which only returned once or twice a year."[32]

Blintiff has investigated the early Medieval networks of market towns across Europe and suggests that by the 12th century there was an upsurge in the number of market towns and the emergence of merchant circuits as traders bulked up surpluses from smaller regional, different day markets and resold them at the larger centralized market towns.[33] Market-places appear to have emerged independently outside Europe. The Grand Bazaar in Istanbul is often cited as the world's oldest continuously-operating market; its construction began in 1455. The Spanish conquistadors wrote glowingly of markets in the Americas. In the 15th century, the Mexica (Aztec) market of Tlatelolco was the largest in all the Americas.[34]

English market towns were regulated from a relatively early period. The English monarchs awarded a charter to local Lords to create markets and fairs for a town or village. This charter would grant the lords the right to take tolls and also afford some protection from rival markets. For example, once a chartered market was granted for specific market days, a nearby rival market could not open on the same days.[35] Across the boroughs of England, a network of chartered markets sprang up between the 12th and 16th centuries, giving consumers reasonable choice in the markets they preferred to patronize.[36] A study on the purchasing habits of the monks and other individuals in medieval England, suggests that consumers of the period were relatively discerning. Purchase decisions were based on purchase criteria such as consumers' perceptions of the range, quality, and price of goods. This informed decisions about where to make their purchases and which markets were superior.[37]

Braudel and Reynold have made a systematic study of these European market towns between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries. Their investigation shows that in regional districts markets were held once or twice a week while daily markets were common in larger cities. Gradually over time, permanent shops with regular trading days began to supplant the periodic markets, while peddlers filled in the gaps in distribution. The physical market was characterized by transactional exchange and the economy was characterized by local trading. Braudel reports that, in 1600, goods traveled relatively short distances – grain 5–10 miles; cattle 40–70 miles; wool and woollen cloth 20–40 miles. Following the European age of discovery, goods were imported from afar – calico cloth from India, porcelain, silk and tea from China, spices from India and South-East Asia and tobacco, sugar, rum and coffee from the New World.[38]

English essayist, Joseph Addison, writing in 1711, described the exotic origin of produce available to English society in the following terms:

- "Our Ships are laden with the Harvest of every Climate: Our Tables are stored with Spices, and Oils, and Wines: Our Rooms are filled with Pyramids of China, and adorned with the Workmanship of Japan: Our Morning's Draught comes to us from the remotest Corners of the Earth: We repair our Bodies by the Drugs of America and repose ourselves under Indian Canopies. My Friend Sir ANDREW calls the Vineyards of France our Gardens; the Spice-Islands our Hot-beds; the Persians our Silk-Weavers, and the Chinese our Potters. Nature indeed furnishes us with the bare Necessaries of Life, but Traffick gives us greater Variety of what is Useful, and at the same time supplies us with every thing that is Convenient and Ornamental."[39]

Luca Clerici has made a detailed study of Vicenza’s food market during the sixteenth century. He found that there were many different types of reseller operating out of the markets. For example, in the dairy trade, cheese and butter were sold by the members of two craft guilds (i.e., cheesemongers who were shopkeepers) and that of the so-called ‘resellers’ (hucksters selling a wide range of foodstuffs), and by other sellers who were not enrolled in any guild. Cheesemongers’ shops were situated in the town hall and were very lucrative. Resellers and direct sellers increased the number of sellers, thus increasing competition, to the benefit of consumers. Direct sellers, who brought produce from the surrounding countryside, sold their wares through the central market place and priced their goods at considerably lower rates than cheesemongers.[40]

Retailing in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries

By the 17th century, permanent shops with more regular trading hours were beginning to supplant markets and fairs as the main retail outlet. Provincial shopkeepers were active in almost every English market town. These shopkeepers sold general merchandise, much like a contemporary convenience store or a general store. For example, William Allen, a mercer in Tamworth who died in 1604, sold spices alongside furs and fabrics.[41] William Stout of Lancaster retailed sugar, tobacco, nails and prunes at both his shop and at the central markets. His autobiography reveals that he spent most of his time preparing products for sale at the central market, which brought an influx of customers into town.[42]

As the number of shops grew, they underwent a transformation. The trappings of a modern shop, which had been entirely absent from the sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century store, gradually made way for store interiors and shopfronts that are more familiar to modern shoppers. Prior to the eighteenth century, the typical retail store had no counter, display cases, chairs, mirrors, changing rooms, etc. However, the opportunity for the customer to browse merchandise, touch and feel products began to be available, with retail innovations from the late 17th and early 18th centuries.[43] Glazing was widely used from the early 18th century. English commentators pointed to the speed at which glazing was installed, Daniel Defoe, writing in 1726, noted that "Never was there such painting and guildings, such sashings and looking-glasses as the shopkeepers as there is now."[44]

.jpg)

Outside the major metropolitan cities, few stores could afford to serve one type of clientele exclusively. However, gradually retail shops introduced innovations that would allow them to separate wealthier customers from the "riff raff." One technique was to have a window opening out onto the street from which customers could be served. This allowed the sale of goods to the common people, without encouraging them to come inside. Another solution, that came into vogue from the late sixteenth century was to invite favored customers into a back-room of the store, where goods were permanently on display. Yet another technique that emerged around the same time was to hold a showcase of goods in the shopkeeper's private home for the benefit of wealthier clients. Samuel Pepys, for example, writing in 1660, describes being invited to the home of a retailer to view a wooden jack.[45] The eighteenth-century English entrepreneurs, Josiah Wedgewood and Matthew Boulton, both staged expansive showcases of their wares in their private residences or in rented halls.[46]

Savitt has argued that by the eighteenth century, American merchants, who had been operating as importers and exporters, began to specialize in either wholesale or retail roles. They tended not to specialize in particular types of merchandise, often trading as general merchants, selling a diverse range of product types. These merchants were concentrated in the larger cities. They often provided high levels of credit financing for retail transactions.[47]

%2C_au_Palais-Royal%2C_1825.jpg)

By the late eighteenth century, grand shopping arcades began to emerge across Europe and in the Antipodes. A shopping arcade refers to a multiple-vendor space, operating under a covered roof. Typically, the roof was constructed of glass to allow for natural light and to reduce the need for candles or electric lighting. Some of the earliest examples of shopping arcade appeared in Paris, due to its lack of pavement for pedestrians. Retailers, eager to attract window shoppers by providing a shopping environment away from the filthy streets, began to construct rudimentary arcades. Opening in 1771, the Coliseé, situated on the Champs Elysee, consisted of three arcades, each with ten shops, all running off a central ballroom. For Parisians, the location was seen as too remote and the arcade closed within two years of opening.[29] Inspired by the souks of Arabia, the Galerie de Bois, a series of wooden shops linked the ends of the Palais Royal, opened in 1786 and became a central part of Parisian social life.[48]

The architect, Bertrand Lemoine, described the period, 1786 to 1935, as l’Ère des passages couverts (the Arcade Era).[49] In the European capitals, shopping arcades spread across the continent, reaching their heyday in the early 19th century: the Palais Royal in Paris (opened in 1784); Passage de Feydeau in Paris (opened in 1791) and Passage du Claire in 1799.[29] London's Piccadilly Arcade (opened in 1810); Paris's Passage Colbert (1826) and Milan's Galleria Vittorio Emanuele (1878).[50] Designed to attract the genteel middle class, arcade retailers sold luxury goods at relatively high prices. However, prices were never a deterrent, as these new arcades came to be the place to shop and to be seen. Arcades offered shoppers the promise of an enclosed space away from the chaos that characterised the noisy, dirty streets; a warm, dry space away from the elements, and a safe-haven where people could socialise and spend their leisure time. As thousands of glass covered arcades spread across Europe, they became grander and more ornately decorated. By the mid-nineteenth century, they had become prominent centres of fashion and social life. Promenading in these arcades became a popular nineteenth-century pass-time for the emerging middle classes. The Illustrated Guide to Paris of 1852 summarized the appeal of arcades in the following description:

- "In speaking of the inner boulevards, we have made mention again and again of the arcades which open onto them. These arcades, a recent invention of industrial luxury, are glass-roofed, marble-paneled corridors extending through whole blocks of buildings, whose owners have joined together for such enterprises. Lining both sides of these corridors, which get their light from above, are the most elegant shops so that the arcade is a city, a world in miniature, in which customers will find everything they need."[51]

The Palais-Royal, which opened to Parisians in 1784 and became one of the most important marketplaces in Paris, is generally regarded as the earliest example in the grand shopping arcades.[52] The Palais-Royal was a complex of gardens, shops and entertainment venues situated on the external perimeter of the grounds, under the original colonnades. The area boasted some 145 boutiques, cafés, salons, hair salons, bookshops, museums, and numerous refreshment kiosks as well as two theatres. The retail outlets specialised in luxury goods such as fine jewellery, furs, paintings and furniture designed to appeal to the wealthy elite. Retailers operating out of the Palais complex were among the first in Europe to abandon the system of bartering, and adopt fixed-prices thereby sparing their clientele the hassle of bartering. Stores were fitted with long glass exterior windows which allowed the emerging middle-classes to window shop and indulge in fantasies, even when they may not have been able to afford the high retail prices. Thus, the Palais-Royal became one of the first examples of a new style of shopping arcade, frequented by both the aristocracy and the middle classes. It developed a reputation as being a site of sophisticated conversation, revolving around the salons, cafés, and bookshops, but also became a place frequented by off-duty soldiers and was a favourite haunt of prostitutes, many of whom rented apartments in the building.[53] London's Burlington Arcade, which opened in 1819, positioned itself as an elegant and exclusive venue from the outset.[54] Other notable nineteenth-century grand arcades include the Galeries Royales Saint-Hubert in Brussels which was inaugurated in 1847, Istanbul's Çiçek Pasajı opened in 1870 and Milan's Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II first opened in 1877. Shopping arcades were the precursor to the modern shopping mall.

While the arcades were the province of the bourgeoisie, a new type of retail venture emerged to serve the needs of the working poor. John Stuart Mill wrote about the rise of the co-operative retail store, which he witnessed first-hand in the mid-nineteenth century. Stuart Mill locates these co-operative stores within a broader co-operative movement which was prominent in the industrial city of Manchester and in the counties of Yorkshire and Lancashire. He documents one of the early co-operative retail stores in Rochdale in Manchester, England, "In 1853, the Store purchased for £745, a warehouse (freehold) on the opposite side of the street, where they keep and retail their stores of flour, butcher's meat, potatoes, and kindred articles." Stuart Mill also quoted a contemporary commentator who wrote of the benefits of the co-operative store:

Buyer and seller meet as friends; there is no overreaching on one side, and no suspicion on the other... These crowds of humble working men, who never knew before when they put good food in their mouths, whose every dinner was adulterated, whose shoes let in the water a month too soon, whose waistcoats shone with devil's dust, and whose wives wore calico that would not wash, now buy in the markets like millionaires, and as far as pureness of food goes, live like lords.[55]

Retailing in the modern era

The modern era of retailing is defined as the period from the industrial revolution to the 21st century.[56] In major cities, the department store emerged in the mid- to late 19th century, and permanently reshaped shopping habits, and redefined concepts of service and luxury. The term, "department store" originated in America. In 19th-century England, these stores were known as emporia or warehouse shops.[57] In London, the first department stores appeared in Oxford Street and Regent Street, where they formed part of a distinctly modern shopping precinct.[58] When London draper, William Whiteley attempted to transform his Bayswater drapery store into a department store by adding a meat and vegetable department and an Oriental Department in around 1875, he met with extreme resistance from other shop-keepers, who resented that he was encroaching on their territory and poaching their customers.[59] Before long, however, major department stores began to open across the US, Britain and Europe from the mid-nineteenth century, including Harrod's of London in 1834; Kendall's in Manchester in 1836; Selfridges of London in 1909; Macy's of New York in 1858; Bloomingdale's in 1861; Sak's in 1867; J.C. Penney in 1902; Le Bon Marché of France in 1852 and Galeries Lafayette of France in 1905.[60] Other twentieth-century innovations in retailing included chain stores, mail-order, multi-level marketing (pyramid selling or network marketing, c. 1920s), party plans (c. 1930s) and B2C e-commerce.[61]

Many of the early department stores were more than just a retail emporium; rather they were venues where shoppers could spend their leisure time and be entertained. Some department stores offered reading rooms, art galleries and concerts. Most department stores had tea-rooms or dining rooms and offered treatment areas where ladies could indulge in a manicure. The fashion show, which originated in the US in around 1907, became a staple feature event for many department stores and celebrity appearances were also used to great effect. Themed events featured wares from foreign shores, exposing shoppers to the exotic cultures of the Orient and Middle-East.[62] One such market that used themed events was the Dayton Arcade. Its opening day celebrations in 1904 used themed stalls to introduce shoppers to goods from around the world.[63]

During this period, retailers worked to develop modern retail marketing practices. Pioneering merchants who contributed to modern retail marketing and management methods include: A. T. Stewart, Potter Palmer, John Wanamaker, Montgomery Ward, Marshall Field, Richard Warren Sears, Rowland Macy, J.C. Penney, Fred Lazarus, brothers Edward and William Filene and Sam Walton.[64]

Retail, using mail order, came of age during the mid-19th century. Although catalogue sales had been used since the 15th century, this method of retailing was confined to a few industries such as the sale of books and seeds. However, improvements in transport and postal services led several entrepreneurs on either side of the Atlantic to experiment with catalogue sales. In 1861, Welsh draper Pryce Pryce-Jones sent catalogues to clients who could place orders for flannel clothing which was then despatched by post. This enabled Pryce-Jones to extend his client base across Europe.[65] A decade later, the US retailer, Montgomery Ward also devised a catalogue sales and mail-order system. His first catalogue which was issued in August 1872 consisted of an 8 in × 12 in (20 cm × 30 cm) single-sheet price list, listing 163 items for sale with ordering instructions for which Ward had written the copy. He also devised the catch-phrase "satisfaction guaranteed or your money back" which was implemented in 1875.[66] By the 1890s, Sears and Roebuck were also using mail order with great success.

Edward Filene, a proponent of the scientific approach to retail management, developed the concept of the automatic bargain Basement. Although Filene's basement was not the first ‘bargain basement’ in the U.S., the principles of ‘automatic mark-downs’ generated excitement and proved very profitable. Under Filene's plan, merchandise had to be sold within 30 days or it was marked down; after a further 12 days, the merchandise was further reduced by 25% and if still unsold after another 18 days, a further markdown of 25% was applied. If the merchandise remained unsold after two months, it was given to charity.[67] Filene was a pioneer in employee relations. He instituted a profit sharing program, a minimum wage for women, a 40-hour work week, health clinics and paid vacations. He also played an important role in encouraging the Filene Cooperative Association, "perhaps the earliest American company union". Through this channel he engaged constructively with his employees in collective bargaining and arbitration processes.[68]

In the post-war period, an American architect, Victor Gruen developed a concept for a shopping mall; a planned, self-contained shopping complex complete with an indoor plaza, statues, planting schemes, piped music, and car-parking. Gruen's vision was to create a shopping atmosphere where people felt so comfortable, they would spend more time in the environment, thereby enhancing opportunities for purchasing. The first of these malls opened at Northland Mall near Detroit in 1954. He went on to design some 50 such malls. Due to the success of the mall concept, Gruen was described as "the most influential architect of the twentieth century by a journalist in the New Yorker."[69]

Throughout the twentieth century, a trend towards larger store footprints became discernible. The average size of a U.S. supermarket grew from 31,000 square feet (2,900 m2) square feet in 1991 to 44,000 square feet (4,100 m2) square feet in 2000. In 1963, Carrefour opened the first hypermarket in St Genevieve-de-Bois, near Paris, France.[70] By the end of the twentieth century, stores were using labels such as "mega-stores" and "warehouse" stores to reflect their growing size. In Australia, for example, the popular hardware chain, Bunnings has shifted from smaller "home centres" (retail floor space under 5,000 square metres (54,000 sq ft)) to "warehouse" stores (retail floor space between 5,000 square metres (54,000 sq ft) and 21,000 square metres (230,000 sq ft)) in order to accommodate a wider range of goods and in response to population growth and changing consumer preferences.[71] The upward trend of increasing retail space was not consistent across nations and led in the early 21st century to a 2-fold difference in square footage per capita between the United States and Europe.[72]

As the 21st century takes shape, some indications suggest that large retail stores have come under increasing pressure from online sales models and that reductions in store size are evident.[73] Under such competition and other issues such as business debt,[74] there has been a noted business disruption called the retail apocalypse in recent years which several retail businesses, especially in North America, are sharply reducing their number of stores, or going out of business entirely.

Retail strategy

The distinction between "strategic" and "managerial" decision-making is commonly used to distinguish "two phases having different goals and based on different conceptual tools. Strategic planning concerns the choice of policies aiming at improving the competitive position of the firm, taking account of challenges and opportunities proposed by the competitive environment. On the other hand, managerial decision-making is focused on the implementation of specific targets."[75]

In retailing, the strategic plan is designed to set out the vision and provide guidance for retail decision-makers and provide an outline of how the product and service mix will optimize customer satisfaction. As part of the strategic planning process, it is customary for strategic planners to carry out a detailed environmental scan which seeks to identify trends and opportunities in the competitive environment, market environment, economic environment and statutory-political environment. The retail strategy is normally devised or reviewed every 3– 5 years by the chief executive officer.

The strategic retail analysis typically includes following elements:[76]

- * Market analysis

- Market size, stage of market, market competitiveness, market attractiveness, market trends

- * Customer analysis

- Market segmentation, demographic, geographic and psychographic profile, values and attitudes, shopping habits, brand preferences, analysis of needs and wants, media habits

- * Internal analysis

- Other capabilities e.g. human resource capability, technological capability, financial capability, ability to generate scale economies or economies of scope, trade relations, reputation, positioning, past performance

- * Competition analysis

- Availability of substitutes, competitor's strengths and weaknesses, perceptual mapping, competitive trends

- * Review of product mix

- Sales per square foot, stock-turnover rates, profitability per product line

- * Review of distribution channels

- Lead-times between placing order and delivery, cost of distribution, cost efficiency of intermediaries

- * Evaluation of the economics of the strategy

- Cost-benefit analysis of planned activities

At the conclusion of the retail analysis, retail marketers should have a clear idea of which groups of customers are to be the target of marketing activities. Not all elements are, however, equal, often with demographics, shopping motivations, and spending directing consumer activities.[77] Retail research studies suggest that there is a strong relationship between a store's positioning and the socio-economic status of customers.[78] In addition, the retail strategy, including service quality, has a significant and positive association with customer loyalty.[79] A marketing strategy effectively outlines all key aspects of firms' targeted audience, demographics, preferences. In a highly competitive market, the retail strategy sets up long-term sustainability. It focuses on customer relationships, stressing the importance of added value, customer satisfaction and highlights how the store's market positioning appeals to targeted groups of customers.[80]

The retail marketing mix

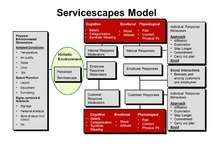

See also product management; promotion mix; marketing mix; price; servicescapes and retail design

Once the strategic plan is in place, retail managers turn to the more managerial aspects of planning. A retail mix is devised for the purpose of coordinating day-to-day tactical decisions. The retail marketing mix typically consists of six broad decision layers including product decisions, place decisions, promotion, price, personnel and presentation (also known as physical evidence). The retail mix is loosely based on the marketing mix, but has been expanded and modified in line with the unique needs of the retail context. A number of scholars have argued for an expanded marketing, mix with the inclusion of two new Ps, namely, Personnel and Presentation since these contribute to the customer's unique retail experience and are the principal basis for retail differentiation. Yet other scholars argue that the Retail Format (i.e. retail formula) should be included.[81] The modified retail marketing mix that is most commonly cited in textbooks is often called the 6 Ps of retailing (see diagram at right).[82][83]

Product

The primary product-related decisions facing the retailer are the product assortment (what product lines, how many lines and which brands to carry); the type of customer service (high contact through to self-service) and the availability of support services (e.g. credit terms, delivery services, after sales care). These decisions depend on careful analysis of the market, demand, competition as well as the retailer's skills and expertise.

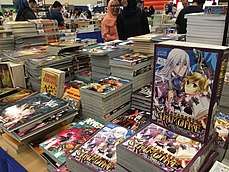

Product assortment

The term product assortment refers to the combination of both product breadth and depth. The main characteristics of a company's product assortment are:[84]

- (1) the length or number of products lines

- the number of different products carried by a store

- (2) the breadth

- refers to the variety of product lines that a store offers. It is also known as product assortment width, merchandise breadth, and product line width.:

- (3) depth or number of product varieties within a product line

- the number of each item or particular styles carried by a store

- (4) consistency

- how products relate to each other in a retail environment.

For a retailer, finding the right balance between breadth and depth can be a key to success. An average supermarket might carry 30,000–60,000 different product lines (product length or assortment), but might carry up to 100 different types of toothpaste (product depth).[85] Speciality retailers typically carry fewer product lines, perhaps as few as 20 lines, but will normally stock greater depth. Costco, for example, carries 5,000 different lines while Aldi carries just 1,400 lines per store.[86]

Large assortments offer consumers many benefits, notably increased choice and the possibility that the consumer will be able to locate the ideal product. However, for the retailer, larger assortments incur costs in terms of record-keeping, managing inventory, pricing and risks associated with wastage due to spoiled, shopworn or unsold stock. Carrying more stock also exposes the retailer to higher risks in terms of slow-moving stock and lower sales per square foot of store space. On the other hand, reducing the number of product lines can generate cost savings through increased stock turnover by eliminating slow-moving lines, fewer stockouts, increased bargaining power with suppliers, reduced costs associated with wastage and carrying inventory, and higher sales per square foot which means more efficient space utilisation.

When determining the number of product lines to carry, the retailer must consider the store type, store's physical storage capacity, the perishability of items, expected turnover rates for each line and the customer's needs and expectations.

Customer service and supporting services

Customer service is the "sum of acts and elements that allow consumers to receive what they need or desire from [the] retail establishment." Retailers must decide whether to provide a full service outlet or minimal service outlet, such as no-service in the case of vending machines; self-service with only basic sales assistance or a full service operation as in many boutiques and speciality stores. In addition, the retailer needs to make decisions about sales support such as customer delivery and after sales customer care.

Retailing services may also include the provision of credit, delivery services, advisory services, exchange/ return services, product demonstration, special orders, customer loyalty programs, limited-scale trial, advisory services and a range of other supporting services. Retail stores often seek to differentiate along customer service lines. For example, some department stores offer the services of a stylist; a fashion advisor, to assist customers selecting a fashionable wardrobe for the forthcoming season, while smaller boutiques may allow regular customers to take goods home on approval, enabling the customer to try out goods before making the final purchase. The variety of supporting services offered is known as the service type. At one end of the spectrum, self-service operators offer few basic support services. At the other end of the spectrum, full-service operators offer a broad range of highly personalised customer services to augment the retail experience.[87]

When making decisions about customer service, the retailer must balance the customer's desire for full-service against the customer's willingness to pay for the cost of delivering supporting services. Self-service is a very cost efficient way of delivering services since the retailer harnesses the customers labour power to carry out many of the retail tasks. However, many customers appreciate full service and are willing to pay a premium for the benefits of full-service.[88]

A sales assistant's role typically includes greeting customers, providing product and service-related information, providing advice about products available from current stock, answering customer questions, finalising customer transactions and if necessary, providing follow-up service necessary to ensure customer satisfaction.[89] For retail store owners, it is extremely important to train personnel with the requisite skills necessary to deliver excellent customer service. Such skills may include product knowledge, inventory management, handling cash and credit transactions, handling product exchange and returns, dealing with difficult customers and of course, a detailed knowledge of store policies. The provision of excellent customer service creates more opportunities to build enduring customer relationships with the potential to turn customers into sources of referral or retail advocates. In the long term, excellent customer service provides businesses with an ongoing reputation and may lead to a competitive advantage. Customer service is essential for several reasons.[90] Firstly, customer service contributes to the customer's overall retail experience. Secondly, evidence suggests that a retail organization that trains its employees in appropriate customer service benefits more than those who do not. Customer service training entails instructing personnel in the methods of servicing the customer that will benefit corporations and businesses. It is important to establish a bond amongst customers-employees known as Customer relationship management.[91]

.jpg)

Types of customer service

There are several ways the retailer can deliver services to consumers:

- Counter service, where goods are out of reach of buyers and must be obtained from the seller. This type of retail is common for small expensive items (e.g. jewellery) and controlled items like medicine and liquor.

- Curbside pickup, where orders are placed online, via a mobile app, or called in, then the customer picks up the product on the property of but outside of the physical store. The coronavirus pandemic is making curbside pickup much more valuable to customers[92]

- Ship to Store, where products are ordered online and can be picked up at the retailer's main store

- Delivery, where goods are shipped directly to consumer's homes or workplaces.

- Mail order from a printed catalogue was invented in 1744 and was common in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Ordering by telephone was common in the 20th century, either from a catalog, newspaper, television advertisement or a local restaurant menu, for immediate service (especially for pizza delivery), remaining in common use for food orders. Internet shopping – a form of delivery – has eclipsed phone-ordering, and, in several sectors – such as books and music – all other forms of buying. There is increasing competitor pressure to deliver consumer goods – especially those offered online – in a more timely fashion. Large online retailers such as Amazon.com are continually innovating and as of 2015 offer one-hour delivery in certain areas. They are also working with drone technology to provide consumers with more efficient delivery options. Direct marketing, including telemarketing and television shopping channels, are also used to generate telephone orders. started gaining significant market share in developed countries in the 2000s.

- Door-to-door sales, where the salesperson sometimes travels with the goods for sale.

- Self-service, where goods may be handled and examined prior to purchase.

- Digital delivery or Download, where intangible goods, such as music, film, and electronic books and subscriptions to magazines, are delivered directly to the consumer in the form of information transmitted either over wires or air-waves and is reconstituted by a device which the consumer controls (such as an MP3 player; see digital rights management). The digital sale of models for 3D printing also fits here, as do the media leasing types of services, such as streaming.

Place

Place decisions are primarily concerned with consumer access and may involve location, space utilisation and operating hours.

Location

Also see Site selection

The perspective of marketing in large-scale enterprises is based on the theory of supply chain management; it emphasizes that the suppliers, large-scale retail enterprises, and customers form a chain of cooperative marketing that establishes mutually beneficial long-term relationships. Relationship marketing of huge retail enterprises from the perspective of supply chain mainly includes two relationship markets, supplier relationships, and customer relationships, as the two greatest influences on retail profits are suppliers and customers. First, as the supplier of commodities to retail enterprises, it directly determines the procurement cost of commodities to retail enterprises, which is mainly reflected in the purchase price of commodities themselves, the cost incurred in the procurement process, and the loss cost caused by unstable supply of commodities. In addition, the good relationship with supplier interaction, large retail enterprises can also promote the suppliers timely grasp the market information, improved or innovative products according to customer demand, which contributed to the retail enterprises improve the market competitiveness of the goods are sold, so the retail enterprise's relationship with the supplier directly affects the retail enterprises in the commodity market competitive. Second, due to the transfer of advantages between buyers and sellers, the retail industry has turned to the buyer's market, and consumers have become the key resources for major retailers to compete with each other.[93] Therefore, it is very important to establish a good relationship with clients and improve customer loyalty. The relationship marketing of customer relationship market regards the transaction with clients as a long term activity. Retail enterprises should pursue long-term mutual benefit maximization rather than a single transaction sales profit maximization. This requires large retail enterprises to establish a customer-oriented trading relationship with the customer relationship market. Retail stores are typically located where market opportunities are optimal – high traffic areas, central business districts. Selecting the right site can be a major success factor. When evaluating potential sites, retailers often carry out a trade area analysis; a detailed analysis designed to approximate the potential patronage area. Techniques used in trade area analysis include: Radial (ring) studies; Gravity models and Drive time analyses.

In addition, retailers may consider a range of both qualitative and quantitative factors to evaluate to potential sites under consideration:

Macro factors

- Macro factors include market characteristics (demographic, economic and socio-cultural), demand, competition and infrastructure (e.g. the availability of power, roads, public transport systems)

Micro factors

- Micro factors include the size of the site (e.g. availability of parking), access for delivery vehicles

Channels

A major retail trend has been the shift to multi-channel retailing. To counter the disruption caused by online retail, many bricks and mortar retailers have entered the online retail space, by setting up online catalogue sales and e-commerce websites. However, many retailers have noticed that consumers behave differently when shopping online. For instance, in terms of choice of online platform, shoppers tend to choose the online site of their preferred retailer initially, but as they gain more experience in online shopping, they become less loyal and more likely to switch to other retail sites.[94] Online stores are usually available 24 hours a day, and many consumers in Western countries have Internet access both at work and at home.

Pricing strategy and tactics

See also Pricing Strategies

The broad pricing strategy is normally established in the company's overall strategic plan. In the case of chain stores, the pricing strategy would be set by head office. Broadly, there are six approaches to pricing strategy mentioned in the marketing literature:

- Operations-oriented pricing: where the objective is to optimise productive capacity, to achieve operational efficiencies, or to match supply and demand through varying prices. In some cases, prices might be set to demarket.[95]

- Revenue-oriented pricing: (also known as profit-oriented pricing or cost-based pricing) – where the marketer seeks to maximise the profits (i.e., the surplus income over costs) or simply to cover costs and break even.[95]

- Customer-oriented pricing: where the objective is to maximise the number of customers; encourage cross-selling opportunities or to recognise different levels in the customer's ability to pay.[95]

- Value-based pricing: (also known as image-based pricing) occurs where the company uses prices to signal market value or associates price with the desired value position in the mind of the buyer. The aim of value-based pricing is to reinforce the overall positioning strategy e.g. premium pricing posture to pursue or maintain a luxury image.[96][97]

- Relationship-oriented pricing: where the marketer sets prices in order to build or maintain relationships with existing or potential customers.[98]

- Socially-oriented pricing: Where the objective is to encourage or discourage specific social attitudes and behaviours. e.g. high tariffs on tobacco to discourage smoking.[99]

Pricing tactics

When decision-makers have determined the broad approach to pricing (i.e., the pricing strategy), they turn their attention to pricing tactics. Tactical pricing decisions are shorter term prices, designed to accomplish specific short-term goals. The tactical approach to pricing may vary from time to time, depending on a range of internal considerations (e.g. the need to clear surplus inventory) or external factors (e.g. a response to competitive pricing tactics). Accordingly, a number of different pricing tactics may be employed in the course of a single planning period or across a single year. Typically store managers have the necessary latitude to vary prices on individual lines provided that they operate within the parameters of the overall strategic approach.

Retailers must also plan for customer preferred payment modes – e.g. cash, credit, lay-by, Electronic Funds Transfer at Point-of-Sale (EFTPOS). All payment options require some type of handling and attract costs. If credit is to be offered, then credit terms will need to be determined. If lay-by is offered, then the retailer will need to take into account the storage and handling requirements. If cash is the dominant mode of payment, the retailer will need to consider small change requirements, the number of cash floats required, wages costs associated with handling large volumes of cash and the provision of secure storage for change floats. Large retailers, handling significant volumes of cash, may need to hire security service firms to carry the day's takings and deliver supplies of small change. A small, but increasing number of retailers are beginning to accept newer modes of payment including PayPal and Bitcoin.[100] For example, Subway (US) recently announced that it would accept Bitcoin payments.[101]

Contrary to common misconception, price is not the most important factor for consumers, when deciding to buy a product.[102]

Pricing tactics that are commonly used in retail include:

- Discount pricing

Discount pricing is where the marketer or retailer offers a reduced price. Discounts in a variety of forms – e.g. quantity discounts, loyalty rebates, seasonal discounts, periodic or random discounts etc.[103]

- Everyday low prices (EDLP)

Everyday low prices refers to the practice of maintaining a regular low price-low price – in which consumers are not forced to wait for discounting or specials. This method is extensively used by supermarkets.[104]

- High-low pricing

High-low pricing refers to the practice of offering goods at a high price for a period of time, followed by offering the same goods at a low price for a predetermined time. This practice is widely used by chain stores selling homewares. The main disadvantage of the high-low tactic is that consumers tend to become aware of the price cycles and time their purchases to coincide with a low-price cycle.[104][105]

- Loss leader

A loss leader is a product that has a price set below the operating margin. Loss leadering is widely used in supermarkets and budget-priced retail outlets where it is intended to generate store traffic. The low price is widely promoted and the store is prepared to take a small loss on an individual item, with an expectation that it will recoup that loss when customers purchase other higher priced-higher margin items. In service industries, loss leadering may refer to the practice of charging a reduced price on the first order as an inducement and with anticipation of charging higher prices on subsequent orders.

- Price bundling

Price bundling (also known as product bundling) occurs where two or more products or services are priced as a package with a single price. There are several types of bundles: pure bundles where the goods can only be purchased as a package or mixed bundles where the goods can be purchased individually or as a package. The prices of the bundle are typically less than when the two items are purchased separately.[106] Price bundling is extensively used in the personal care sector to price cosmetics and skincare.

- Price lining

Price lining is the use of a limited number of prices for all products offered by a business. Price lining is a tradition started in the old five and dime stores in which everything cost either 5 or 10 cents. In price lining, the price remains constant but the quality or extent of product or service adjusted to reflect changes in cost. The underlying rationale of this tactic is that these amounts are seen as suitable price points for a whole range of products by prospective customers. It has the advantage of ease of administering, but the disadvantage of inflexibility, particularly in times of inflation or unstable prices. Price lining continues to be widely used in department stores where customers often note racks of garments or accessories priced at predetermined price points e.g. separate racks of men's ties, where each rack is priced at $10, $20 and $40.

- Promotional pricing

Promotional pricing is a temporary measure that involves setting prices at levels lower than normally charged for a good or service. Promotional pricing is sometimes a reaction to unforeseen circumstances, as when a downturn in demand leaves a company with excess stocks; or when competitive activity is making inroads into market share or profits.[107]

- Psychological pricing

Psychological pricing is a range of tactics designed to have a positive psychological impact. Price tags using the terminal digit "9", ($9.99, $19.99 or $199.99) can be used to signal price points and bring an item in at just under the consumer's reservation price. Psychological pricing is widely used in a variety of retail settings.[108]

Personnel and staffing

Because patronage at a retail outlet varies, flexibility in scheduling is desirable. Employee scheduling software is sold, which, using known patterns of customer patronage, more or less reliably predicts the need for staffing for various functions at times of the year, day of the month or week, and time of day. Usually needs vary widely. Conforming staff utilization to staffing needs requires a flexible workforce which is available when needed but does not have to be paid when they are not, part-time workers; as of 2012 70% of retail workers in the United States were part-time. This may result in financial problems for the workers, who while they are required to be available at all times if their work hours are to be maximized, may not have sufficient income to meet their family and other obligations.[109]

Selling and sales techniques

Also see Personal selling

Burwood_McDonalds.jpg)

Retailers can employ different techniques to enhance sales volume and to improve the customer experience:

- Add-on, Upsell or Cross-sell.

- Upselling and cross-selling are sometimes known as suggestive selling. When the consumer has selected their main purchase, sales assistants can try to sell the customer on a premium brand or higher quality item (up-selling) or can suggest complementary purchases (cross-selling). For instance, if a customer purchases a non-stick frypan, the sales assistant might suggest plastic slicers that do not damage the non-stick surface.

- Selling on value

- Skilled sales assistants find ways to focus on value rather than price. Selling on value often involves identifying a product’s unique features. Adding value to goods or services such as a free gift or buy 1 get 1 free adds value to customers whereas the store is gaining sales[110]

- Know when to close the sale

- Sales staff must learn to recognise when the customer is ready to make a purchase. If the sales person feels that the customer is ready, then they may seek to gain commitment and close the sale. Experienced sales staff soon learn to recognise specific verbal and non-verbal cues that signal the client's readiness to buy. For instance, if a customer begins to handle the merchandise, this may indicate a state of buyer interest. Clients also tend to employ different types of questions throughout the sales process. General questions such as, "Does it come in any other colours (or styles)?" indicate only a moderate level of interest. However, when clients begin to ask specific questions, such as "Do you have this model in black?" then this often indicates that the prospect is approaching readiness to buy.[111] When the sales person believes that the prospective buyer is ready to make the purchase, a trial close might be used to test the waters. A trial close is simply any attempt to confirm the buyer's interest in finalising the sale. An example of a trial close, is "Would you be requiring our team to install the unit for you?" or "Would you be available to take delivery next Thursday?" If the sales person is unsure about the prospect's readiness to buy, they might consider using a 'trial close.' The salesperson can use several different techniques to close the sale; including the ‘alternative close’, the ‘assumptive close’, the ‘summary close’, or the ‘special-offer close’, among others.

Promotion

In the 1980s, the customary sales concept in the retail industry began to show many disadvantages. Many transactions cost too much, and the industry was unable to retain customers as it only paid attention to the process of a single transaction rather than to marketing for customer development and maintenance. The traditional marketing theory holds that transactions are one-time value exchange processes and the means of exchanging goods needed by both parties. Accordingly, when the transaction is completed, the relationship between the two parties will also end, so the theory is called "transactional marketing". Transactional marketing aims to find target consumers, then negotiate, trade, and finally end relationships to complete the transaction. In this one-time transaction process, both parties aim to maximize their own interests. As a result, transactional marketing raises follow-up problems such as poor after-sales service quality and a lack of feedback channels for both parties. In addition, because retail enterprises needed to redevelop client relationships for each transaction, marketing costs were high and customer retention was low. All these downsides to transactional marketing gradually pushed the retail industry towards establishing long-term cooperative relationships with customers. Through this lens, enterprises began to focus on the process from transaction to relationship.[112] While expanding the sales market and attracting new customers is very important for the retail industry, it is also important to establish and maintain long term good relationships with previous customers, hence the name of the underlying concept, "relational marketing". Under this concept, retail enterprises value and attempt to improve relationships with customers, as customer relationships are conducive to maintaining stability in the current competitive retail market, and are also the future of retail enterprises.

One of the unique aspects of retail promotions is that two brands are often involved; the store brand and the brands that make up the retailer's product range. Retail promotions that focus on the store tend to be ‘image’ oriented, raising awareness of the store and creating a positive attitude towards the store and its services. Retail promotions that focus on the product range, are designed to cultivate a positive attitude to the brands stocked by the store, in order to indirectly encourage favourable attitudes towards the store itself.[113] Some retail advertising and promotion is partially or wholly funded by brands and this is known as co-operative (or co-op) advertising.[114]

Retailers make extensive use of advertising via newspapers, television and radio to encourage store preference. In order to up-sell or cross-sell, retailers also use a variety of in-store sales promotional techniques such as product demonstrations, samples, point-of-purchase displays, free trial, events, promotional packaging and promotional pricing. In grocery retail, shelf wobblers, trolley advertisements, taste tests and recipe cards are also used. Many retailers also use loyalty programs to encourage repeat patronage.

Presentation

See Merchandising; Servicescapes; Retail design

Presentation refers to the physical evidence that signals the retail image. Physical evidence may include a diverse range of elements – the store itself including premises, offices, exterior facade and interior layout, websites, delivery vans, warehouses, staff uniforms.

Designing retail spaces

The environment in which the retail service encounter occurs is sometimes known as the retail servicescape.[115] The store environment consists of many elements such as smells, the physical environment (furnishings, layout and functionality), ambient conditions (lighting, temperature, noise) as well as signs, symbols and artifacts (e.g. sales promotions, shelf space, sample stations, visual communications). Collectively, these elements contribute to the perceived retail servicescape or the overall atmosphere and can influence both the customer's cognitions, emotions and their behaviour within the retail space.

Relationship between market

Large retail enterprises of relationship marketing refers to a large retail enterprise with suppliers, customers, internal organization, channel distributors, market impact, and other competitors such as the interests of the enterprise marketing process related everything to establish and maintain good relations, thus maximizing the interests of the large retail enterprise in the long-term marketing activities, it was based on the relationship marketing concept as the core of innovation. Different from traditional marketing concepts, relationship marketing focuses on maintaining long-term good relations with relevant parties on marketing activities. The ultimate goal of relationship marketing is tantamount to maximize the long term interests of enterprises.

The marketing activities of large retail enterprises mainly have six relationship markets, which are supplier relationship market, customer relationship market, enterprise internal relationship market, intermediary relationship market at all levels, enterprise marketing activities influence relationship market and industry competitor relationship market. Among these six relational markets, supply relational market and customer relational market are the two markets that have the greatest influence on the relationship marketing of large retail enterprises. Substantial retail enterprises usually have two sources of profit. The principal source of profit is to reduce the purchase price from suppliers. The other is to develop new customers and keep old clients, so as to expand the market sales of goods. In addition, the extra four related markets have an indirect impact on the marketing activities of large retail enterprises.[116] The internal relationship market of an enterprise can be divided into several different types of relationships according to distinct objects, such as employee relationship market, department relationship market, shareholder relationship market and the mutual relations among the relationship markets. The purpose of carrying out relationship marketing is to promote the cohesion and innovation ability of enterprises and maximize the long term interests of enterprises. Another relationship of relationship marketing middlemen is the relationship between market and intermediary in the process of corporate marketing is playing the intermediary role between suppliers and customers, in the current increasingly fierce market competition, more important distribution channels for enterprises, but for retail enterprises, too much sales levels will increase the cost of sales of the enterprise. Therefore, large retail enterprises should realize the simplification of sales channel level by reasonably selecting suppliers. Large-scale retail enterprises purchasing goods to suppliers with procurement scale advantage, can directly contact with the product manufacturing, with strong bargaining power, therefore, direct contact with the manufacturer is a large retail enterprise to take the main purchasing mode, it is a terminal to the starting point of zero level channel purchasing mode, therefore, the elimination of middlemen, so as to make the large retail enterprise in the marketing activity, the dealer relationship market is not so important. Then there is the enterprise influence relationship market, which is a relational marketing influence in the enterprise supply chain. It mainly guides and standardizes the advance direction of enterprises through formulating systems at the macro level. The relationship market mainly includes the relationship between the relevant government departments at all levels where the enterprise is located, the relationship with the industry association to which the enterprise belongs, and the relationship with all kinds of public organizations, etc., and the enterprise influence itself cannot directly affect the marketing activities of the enterprise. The final relational market is the industry's competitors, potential competitors, alternative competitors and so on. How to correctly deal with the relationship between competitors and the market has become a problem that large retail enterprises need to solve.

Retail designers pay close attention to the front of the store, which is known as the decompression zone.This is usually an open space in the entrance of the store to allow customers to adjust to their new environment. An open-plan floor design is effective in retail as it allows customers to see everything. In terms of the store's exterior, the side of the road cars normally travel, determines the way stores direct customers. New Zealand retail stores, for instance, would direct customers to the left.

In order to maximise the number of selling opportunities, retailers generally want customers to spend more time in a retail store. However, this must be balanced against customer expectations surrounding convenience, access and realistic waiting times. The overall aim of designing a retail environment is to have customers enter the store, and explore the totality of the physical environment engaging in a variety of retail experiences – from browsing through to sampling and ultimately to purchasing. The retail service environment plays an important role in affecting the customer's perceptions of the retail experience.[117]

.jpg)

The retail environment not only affects quality perceptions, but can also impact on the way that customers navigate their way through the retail space during the retail service encounter. Layout, directional signage, the placement of furniture, shelves and display space along with the store's ambient conditions all affect patron's passage through the retail service system. Layout refers to how equipment, shelves and other furnishings are placed and the relationship between them. In a retail setting, accessibility is an important aspect of layout. For example, the grid layout used by supermarkets with long aisles and gondolas at the end displaying premium merchandise or promotional items, minimises the time customers spend in the environment and makes productive use of available space.[118] The gondola, so favoured by supermarkets, is an example of a retail design feature known as a merchandise outpost and which refers to special displays, typically at or near the end of an aisle, whose purpose is to stimulate impulse purchasing or to complement other products in the vicinity. For example, the meat cabinet at the supermarket might use a merchandise outpost to suggest a range of marinades or spice rubs to complement particular cuts of meat. As a generalisation, merchandise outposts are updated regularly so that they maintain a sense of novelty.[119]

According to Ziethaml et al., layout affects how easy or difficult it is to navigate through a system. Signs and symbols provide cues for directional navigation and also inform about appropriate behaviour within a store. Functionality refers to extent to which the equipment and layout meet the goals of the customer.[120] For instance, in the case of supermarkets, the customer's goal may be to minimise the amount of time spent finding items and waiting at the check-out, while a customer in a retail mall may wish to spend more time exploring the range of stores and merchandise. With respect to functionality of layout, retail designers consider three key issues; circulation – design for traffic-flow and that encourages customers to traverse the entire store; coordination – design that combines goods and spaces in order to suggest customer needs and convenience – design that arranges items to create a degree of comfort and access for both customers and employees.[121]

The way that brands are displayed is also part of the overall retail design. Where a product is placed on the shelves has implications for purchase likelihood as a result of visibility and access. Products placed too high or too low on the shelves may not turn over as quickly as those placed at eye level.[122] With respect to access, store designers are increasingly giving consideration to access for disabled and elderly customers.

Through sensory stimulation retailers can engage maximum emotional impact between a brand and its consumers by relating to both profiles; the goal and experience. Purchasing behaviour can be influenced through the physical evidence detected by the senses of touch, smell, sight, taste and sound.[123] Supermarkets offer taste testers to heighten the sensory experience of brands. Coffee shops allow the aroma of coffee to waft into streets so that passers-by can appreciate the smell and perhaps be lured inside. Clothing garments are placed at arms' reach, allowing customers to feel the different textures of clothing.[123] Retailers understand that when customers interact with products or handle the merchandise, they are more likely to make a purchase.

Within the retail environment, different spaces may be designed for different purposes. Hard floors, such as wooden floors, used in public areas, contrast with carpeted fitting rooms, which are designed to create a sense of homeliness when trying on garments. Peter Alexander, retailer of sleep ware, is renowned for using scented candles in retail stores.

Ambient conditions, such as lighting, temperature and music, are also part of the overall retail environment.[123] It is common for a retail store to play music that relates to their target market. Studies have found that "positively valenced music will stimulate more thoughts and feeling than negatively valenced music", hence, positively valenced music will make the waiting time feel longer to the customer than negatively valenced music.[124] In a retail store, for example, changing the background music to a quicker tempo may influence the consumer to move through the space at a quicker pace, thereby improving traffic flow.[125] Evidence also suggests that playing music reduces the negative effects of waiting since it serves as a distraction.[124] Jewellery stores like Michael Hill have dim lighting with a view to fostering a sense of intimacy.

The design of a retail store is critical when appealing to the intended market, as this is where first impressions are made. The overall servicescape can influence a consumer's perception of the quality of the store, communicating value in visual and symbolic ways. Certain techniques are used to create a consumer brand experience, which in the long run drives store loyalty.[126]

Shopper profiles

Two different strands of research have investigated shopper behaviour. One strand is primarily concerned with shopper motivations. Another stream of research seeks to segment shoppers according to common, shared characteristics. To some extent, these streams of research are inter-related, but each stream offers different types of insights into shopper behaviour.

_(14593807460).jpg)

Babin et al. carried out some of the earliest investigations into shopper motivations and identified two broad motives: utilitarian and hedonic. Utilitarian motivations are task-related and rational. For the shopper with utilitarian motives, purchasing is a work-related task that is to be accomplished in the most efficient and expedient manner. On the other hand, hedonic motives refer to pleasure. The shopper with hedonic motivations views shopping as a form of escapism where they are free to indulge fantasy and freedom. Hedonic shoppers are more involved in the shopping experience.[127]

Many different shopper profiles can be identified. Retailers develop customised segmentation analyses for each unique outlet. However, it is possible to identify a number of broad shopper profiles. One of the most well-known and widely cited shopper typologies is that developed by Sproles and Kendal in the mid-1980s.[128][129][130] Sproles and Kendall's consumer typology has been shown to be relatively consistent across time and across cultures.[131][132] Their typology is based on the consumer's approach to making purchase decisions.[133]

- Quality conscious/Perfectionist: Quality-consciousness is characterised by a consumer's search for the very best quality in products; quality conscious consumers tend to shop systematically making more comparisons and shopping around.

- Brand-conscious: Brand-consciousness is characterised by a tendency to buy expensive, well-known brands or designer labels. Those who score high on brand-consciousness tend to believe that the higher prices are an indicator of quality and exhibit a preference for department stores or top-tier retail outlets.

- Recreation-conscious/Hedonistic: Recreational shopping is characterised by the consumer's engagement in the purchase process. Those who score high on recreation-consciousness regard shopping itself as a form of enjoyment.

- Price-conscious: A consumer who exhibits price-and-value consciousness. Price-conscious shoppers carefully shop around seeking lower prices, sales or discounts and are motivated by obtaining the best value for money