Renewable energy in China

China is the world's leading country in electricity production from renewable energy sources, with over double the generation of the second-ranking country, the United States. By the end of 2018, the country had a total capacity of 728 GW of renewable power, mainly from hydroelectric and wind power. China's renewable energy sector is growing faster than its fossil fuels and nuclear power capacity.

| Part of a series on |

| Renewable energy |

|---|

|

Although China currently has the world's largest installed capacity of hydro, solar and wind power, its energy needs are so large that in 2015 renewable sources provided only 24% of its electricity generation, with most of the remainder provided by coal power plants.[1] In 2017, renewable energy comprised 36.6% of China's total installed electric power capacity, and 26.4% of total power generation, the vast majority from hydroelectric sources.[2] Nevertheless, the share of renewable sources in the energy mix had been gradually rising in recent years.

China sees renewables as a source of energy security and not just only to reduce carbon emission.[3] China's Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Air Pollution issued by China's State Council in September 2013, illustrates the government's desire to increase the share of renewables in China's energy mix.[4] Unlike oil, coal and gas, the supplies of which are finite and subject to geopolitical tensions, renewable energy systems can be built and used wherever there is sufficient water, wind, and sun.[5]

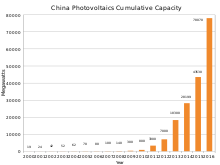

As Chinese renewable manufacturing has grown, the costs of renewable energy technologies have dropped dramatically. Innovation has helped, but the main driver of reduced costs has been market expansion.[5] In 2015, China became the world's largest producer of photovoltaic power, with 43 GW of total installed capacity.[6][7] From 2005 to 2014, production of solar cells in China has expanded 100-fold.[5] However, China is not expected to achieve grid parity – when an alternate source of energy is as cheap or cheaper than power purchased from the grid—until 2022.[8] In 2017, investments in renewable energy amounted to US$279.8 billion worldwide, with China accounting for US$126.6 billion or 45% of the global investments.[9]

Renewable electricity overview

Hydro Waste Wind Biofuels Solar PV Solar thermal Geothermal Tide

| Year | Total | Fossil | Nuclear | Renewable | Total renewable |

% renewable | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coal | Oil | Gas | Hydro | Wind | Solar PV | Biofuels | Waste | Solar thermal | Geo- thermal |

Tide | |||||

| 2008 | 3,481,985 | 2,743,767 | 23,791 | 31,028 | 68,394 | 585,187 | 14,800 | 152 | 14,715 | 0 | 0 | 144 | 7 | 615,005 | 17.66% |

| 2009 | 3,741,961 | 2,940,751 | 16,612 | 50,813 | 70,134 | 615,640 | 26,900 | 279 | 20,700 | 0 | 0 | 125 | 7 | 663,651 | 17.74% |

| 2010 | 4,207,993 | 3,250,409 | 13,236 | 69,027 | 73,880 | 722,172 | 44,622 | 699 | 24,750 | 9,064 | 2 | 125 | 7 | 801,441 | 19.05% |

| 2011 | 4,715,761 | 3,723,315 | 7,786 | 84,022 | 86,350 | 698,945 | 70,331 | 2,604 | 31,500 | 10,770 | 6 | 125 | 7 | 814,288 | 17.27% |

| 2012 | 4,994,038 | 3,785,022 | 6,698 | 85,686 | 97,394 | 872,107 | 95,978 | 6,344 | 33,700 | 10,968 | 9 | 125 | 7 | 1,019,238 | 20.41% |

| 2013 | 5,447,231 | 4,110,826 | 6,504 | 90,602 | 111,613 | 920,291 | 141,197 | 15,451 | 38,300 | 12,304 | 26 | 109 | 8 | 1,127,686 | 20.70% |

| 2014 | 5,678,945 | 4,115,215 | 9,517 | 114,505 | 132,538 | 1,064,337 | 156,078 | 29,195 | 44,437 | 12,956 | 34 | 125 | 8 | 1,307,170 | 23.02% |

| 2015 | 5,859,958 | 4,108,994 | 9,679 | 145,346 | 170,789 | 1,130,270 | 185,766 | 45,225 | 52,700 | 11,029 | 27 | 125 | 8 | 1,425,180 | 24.32% |

| 2016 | 6,217,907 | 4,241,786 | 10,367 | 170,488 | 213,287 | 1,193,374 | 237,071 | 75,256 | 64,700 | 11,413 | 29 | 125 | 11 | 1,581,979 | 25.44% |

| 2017 | 6,452,900 | 248,100 | 1,194,700 | 304,600 | 117,800 | 1,700,000 | 26.34% | ||||||||

| 2018 | 6,994,000 | 294,400 | 1,232,900 | 366,000 | 177,500 | 1,870,000 | 26.73% | ||||||||

As of year end 2014 hydroelectric power remains by far the largest component of renewable electricity production at 1,064 TWh. Wind power provided the next largest share with 156 TWh followed by biofuels at 44 TWh. Solar PV power started from a low base of just 152 GWh in 2008 and has grown rapidly since then to reach over 29 TWh by 2014. The overall share of electricity generated from renewable sources based on the figures in the above table has grown from a little over 17% in 2008 to a little over 23% by 2014. Solar and wind power continue to grow at a rapid pace.

Sources

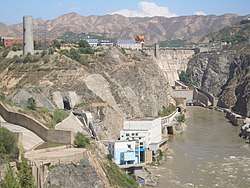

Hydropower

On 6 April 2007, the Gansu Dang River Hydropower Project[10] was registered as a Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) project in accordance with the requirements of the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The project consists of the construction and operation of eight run-of-river hydropower plants providing total capacity of 35.4 GW, which will generate an average of 224 GWh/year. The project is located in Dang Town, Subei Mongolian Autonomous County, Gansu Province, China, and was certified by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) to be in compliance with the "Measures for the Operation and Management of Clean Development Mechanism Projects in China". The power generated by the project will be sold to the Gansu power grid which is part of the China Northwest Regional Power Grid (NWPG). This will displace equivalent amounts of electricity generated by the current mix of power sold to the NWPG. The developer of the Gansu Dang River Hydropower Project, which started construction on 1 November 2004, is the Jiayuguan City Tongyuan Hydropower Co., Ltd. The Letter of Approval of the NDRC permits the Jiayuguan City Tongyuan Hydropower Co. Ltd. to transfer to Japan Carbon Finance, Ltd., an entity approved by the government of Japan no more than 1.2 megatons of carbon dioxide emissions in total Certified Emission Reductions (CERs) over the seven-year period beginning on 1 May 2007, and ending on 30 April 2014.[11]

In 2006 there were 10 GW of installed hydropower capacity that went into operation in China. The National Development and Reform Commission also approved thirteen additional hydropower projects in 2006, which cumulatively will have 19.5 GW of power generating capacity. New hydropower projects that were approved and began construction in 2006 include the Jinsha River Xiangjiaba Dam (6000 MW), the Yalong River (Second Phase) (4800 MW), the Lancang River's Jinghong Dam (1750 MW), the Beipan River(1040 MW), and the Wu River's Silin Dam (1080 MW). In 2005 the following hydroelectric power projects were approved by the NDRC and began construction: the Jinsha River's Xiluo Crossing (12600 MW), the Yellow River's Laxiwa Dam (4200 MW), and the Yalong River (First Phase) (3600 MW).[12]

Wind power

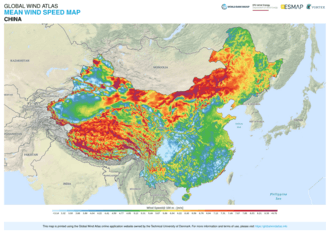

China has the largest wind resources in the world and three-quarters of this natural resource is located at sea.[14] China aims to have 210 GW of wind power capacity by 2020.[15] China encourages foreign companies, especially from the United States, to visit and invest in Chinese wind power generation.[16] However, use of wind energy in China has not always kept up with the remarkable construction of wind power capacity in the country.[4]

In 2008 China was the fourth largest producer of wind power after the United States, Germany, and Spain.[17] At the end of 2008, wind power in China accounted for 12.2 GW of electricity generating capacity. By the end of 2008, at least fifteen Chinese companies were commercially producing wind turbines and several dozen more were producing components. Turbine sizes of 1.5 MW and 2 MW became common. Leading wind power companies were Goldwind, Dongfang, and Sinovel.[18] China also increased the production of small-scale wind turbines to about 80,000 turbines (80 MW) in 2008. Through all these developments, the Chinese wind industry appeared unaffected by the global financial crisis, according to industry observers.[18]

By 2009 China had total installed windpower capacity up to 26 GW.[19] China has identified wind power as a key growth component of the country's economy.[20]

As of 2010, China has become the world's largest maker of wind turbines, surpassing Denmark, Germany, Spain, and the United States.[21] The initial future target set by the Chinese government was 10 GW by 2010,[22] but the total installed capacity for wind power generation in China had already reached 25.1 GW by the end of 2009.[17][23]

In September 2019, Norwegian energy firm Equinor and state-owned China Power International Holding (CPIH) announced their plan to cooperate in developing offshore wind in China and Europe.[24]

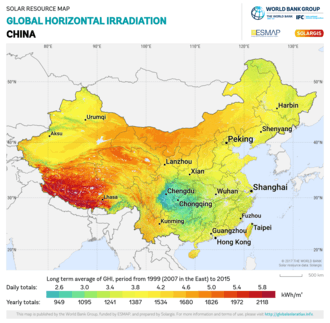

Solar power

China produces 63% of the world's solar photovoltaics (PV).[26] It has emerged as the world's largest manufacturer as of June 2015.[27][28]

Following the new incentive scheme of Golden Sun announced by the government in 2009, there are numerous recent developments and plans announced by industry players that became part of the milestones for solar industry and technology development in China, such as the new thin film solar plant developed by Anwell Technologies in the Henan province using its own proprietary solar technology. The agreement was signed by LDK for a 500 MW solar project in the desert, alongside First Solar and Ordos City. The effort to drive the renewable energy use in China was further assured after the speech of the Chinese President given at the UN climate summit on 22 September 2009 in New York, pledging that China would adopt plans to use 15% of its energy from renewable sources within a decade.[29][30][31]

China has become a world leader in the manufacture of solar photovoltaic technology, with its six biggest solar companies having a combined value of over $15 billion. Around 820 MW of solar PV were produced in China in 2007, second only to Japan.[32]

Biomass and biofuel

China emerged as the world's third largest producer of ethanol-based bio-fuels (after the U.S and Brazil) at the end of the 10th Five Year Plan Period in 2005 and at present ethanol accounts for 20% of total automotive fuel consumption in China.[33] In the 11th Five Year Plan period (2006 through 2010) China planned to develop six megatons/year of fuel ethanol capacity, which is expected to grow to 15 megatons/year by 2020. Despite this level of production, experts say that there will be no threat to food security, though there will be an increasing number of farmers who will be "farming oil" if the price of crude oil continues to increase. Based on planned ethanol projects in some provinces in China, the output of corn would be insufficient to provide the raw material for plants in these provinces. In the recently published World Economic Outlook, the International Monetary Fund expressed concern that there would be increasing competition worldwide between bio-fuels and food consumption for agricultural products and that that competition would likely continue to result in increases in the price of crops.[34]

Work has begun on the ¥250 million Kaiyou Green Energy Biomass (Rice Husks) Power Generating project located in the Suqian City Economic Development Zone in Jiangsu Province. The Kaiyou Green Energy Biomass Power project will generate 144 GWh/year (equivalent to 16.5 MW) and use 200 kilotonnes/year of crop waste as inputs.[35]

Bioenergy is also used at the domestic level in China, both in biomass stoves[36] and by producing biogas from animal manure.[37]

Geothermal

Geothermal resources in China are abundant and widely distributed throughout the country. There are over 2,700 hot springs occurring at the surface, with temperatures exceeding 250 °C. In 1990, the total flow rate of thermal water for direct uses amounted to over 9,500 kg/s, making China the second direct user of geothermal energy in the world. Recognizing geothermal energy as an alternative and renewable energy resource since the 1970s, China has conducted extensive explorations aiming at identifying high temperature resources for electric generation. Until 2006, 181 geothemal systems had been found on mainland China, with an estimated generation potential of 1,740 MW. However, only seven plants, with a total capacity of 32 MW, had been constructed and were operating in 2006.[38]

National laws and policies

After the dissolution of the Energy and Industry Department in 1993, China has been running without a government agency effectively managing the country's energy. Related issues are supervised by multiple organizations such as the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), Ministry of Commerce, State electricity Regulatory Commission (SERC) and so forth. In 2008, the National Energy Administration was founded under the NDRC, however its work has been proven inefficient.[39] In January 2010, the State Council decided to set up a National Energy Commission (NEC), headed by current Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao. The commission will be responsible for drafting a national energy development plan, reviewing energy security and major energy issues and coordinating domestic energy development and international cooperation.[40]

The Chinese government is implementing multiple policies to promote renewable energy. From 2008 to January 2012, China held the top spot in clean energy investment.[41] The Renewable Energy Law passed in 2005 explicitly states in its first chapter that the development and the usage of renewable energy is a prioritized area in energy development.[42] The Twelfth Five-Year Plan, the current plan, also places great emphasis on green energy.[43] Detailed incentive policies and programs include the Golden Sun program, which provides financial subsidies, technology support and market incentives to facilitate the development of the solar power industry;[44] the Suggestions on Promoting Wind Electricity Industry in 2006, which offers preferential policies for wind power development;[45] and many other policies. Besides promoting policies, China has enacted a number of policies to standardize renewable energy products, to prevent environmental damage, and to regulate the price of green energy. These policies include, but are not limited to Renewable Energy Law,[46] the Safety Regulations of Hydropower Dams[47] and the National Standard of Solar Water Heaters.[48]

Several provisions in relevant Chinese laws and regulations address the development of methane gas in rural China. These provisions include Article 54 of the Agriculture Law of the People's Republic of China,[49] Articles 4 and 11 of the Energy Conservation Law of the People's Republic of China,[50] Article 18 of the Renewable Energy Law of the People's Republic of China[51] and Article 12 of the Regulations of the People's Republic of China Concerning Restoring Farmland to Forest.[52]

On 20 April 2007, the Environment and Resources Committee of the National People's Congress and the National Development and Reform Commission convened a conference on the occasion of the first anniversary of the Renewable Energy Law. There were approximately 250 people who attended the conference from the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Science and Technology, the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Construction, the General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine (AQSIQ), the National Bureau of Forestry, the National Power Network Company, science and technology institutes, oil companies, large energy investment companies, companies manufacturing renewable energy equipment, etc. Other conferences included the 3rd Annual China Power & Alternative Energy Summit, held from 16–20 May 2007, at the Swissotel, Beijing; the 2nd China Renewable Energy and Energy Conservation Products and Technology Exhibition, held from 1–3 June 2007, in Beijing at the National Agricultural Exhibition Hall; and the 2007 China International Solar Energy and Photovoltaic Engineering Exhibition, held at the Beijing International Exhibition Center from 25–29 June 2007. The sponsors of the exhibition included the Asia Renewable Energy Association, the China Energy Enterprises Management Association and the China Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation Enterprise Association.

Clean Development Mechanism projects in China

According to the UNFCCC database, by November 2011, China was the leading host nation for CDM projects with 1661 projects (46.32%) of a total of 3586 registered project activities (100%).[53] According to the IGES (Japan), the running total of CERs generated by CDM projects in China at 31 March 2011 was topped by HFC reduction/avoidance projects (365,577 x 1000t/CO2-e) followed by hydro power (227,693), wind power (149,492), N2O decomposition (102,798), and methane recovery (102,067).[54]

According to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, of a total of more than 600 registered CDM Projects worldwide through mid-April 2007, there are now 70 registered CDM projects in China. The pace of Chinese CDM project registration is accelerating; prior to the beginning of 2007 China had 34 registered CDM projects, yet to date in 2007 another 36 Chinese CDM projects have been registered.[55]

The Shanghai Power Transmission and Distribution Joint Stock Company, a subsidiary of the Shanghai Electric and Gas Group Joint Stock Company entered into a joint venture agreement with Canada's Xantrex Technology, Inc, to build a factory to design, manufacture and sell solar and wind power electric and gas electronics products. The new company is in the final stages of the approval process.[56]

According to Theo Ramborst, the General Manager and CEO of Bosch Rexroth (China) Ltd., a subsidiary of the Bosch Group AG, a world leader in controls, transmission and machine hydraulics manufacturing, Bosch Rexroth (China) Ltd. contracted €120 million in wind turbo generator business in China in 2006, a 66% increase year-on-year. Responding to the increase in wind energy business in China, Bosch Rexroth (China) Ltd. invested ¥280 million in October 2006 in plant expansions in Beijing and Changzhou, Jiangsu Province. Earlier in 2006 Bosch Rexroth started up its Shanghai Jinqiao (Golden Bridge) factory, which is involved in the manufacture, installation, distribution and service of transmission and control parts and systems; the Shanghai facility will also serve as Bosch's principal center for technology, personnel and distribution in China.[57]

Environmental protection and energy conservation

According to China's "Energy Blue Paper" recently written by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the average rate of recovery of coal from mining in China is only 30%, less than one-half the rate of recovery throughout the world; the rate of recovery of coal resources in the US, Australia, Germany and Canada is ~80%. The rate of recovery of coal from mining in Shanxi Province, China's largest source of coal is approximately 40%, though the rate of recovery of village and township coal mines in Shanxi Province is only 10%-20%. Cumulatively over the course of the past 20 years (1980–2000) China has wasted upwards of 28 gigatons of coal.[58] The same causes for a low rate of recovery in coal mining — that extraction methods are backward — lead to safety problems in China's coal mining sector. Another reason for the low rate of recovery is that the majority of extraction comes from small-scale mining; of the 346.9 gigatons of coal extracted by China, only 98 gigatons has come from large or mid-sized mines while 250 gigatons are extracted from small mines. Based on coal production in 2005 of 2.19 gigatons and a current rate of recovery of 30%, if China were able to double its rate of recovery it would save approximately 3.5 gigatons of coal.[59]

On 13 April 2007, the Department of Science, Technology and Education of the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture hosted the Asian regional workshop on adaptation to climate change organized by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Climate change will affect Asian countries in different but consistently negative ways. Temperate regions will experience changes in boreal forest cover, while vanishing mountain glaciers will cause problems such as water shortages and increased risks of glacial lake flooding. Coastal zones are under increasing risk from sea level rises as well as pollution and overexploitation of natural resources. In 2006 in China storms, floods, heat and drought killed more than 2,700 people; effects ranged from drought in the southwest of China, which were the worst since records began to be kept in the late nineteenth century, to floods and typhoons in central and southeastern China. The weather events in China in 2006 were seen to be a prelude to weather patterns likely to become more common due to global warming. Topics discussed by representatives of Asian countries and developed countries, international organizations and nongovernmental organizations, included vulnerability assessments, implementing adaptation actions in various sectors of the economy and in specific geographical areas, such as coastal and mountainous regions.[60]

Based on a recently completed survey in 2007, the Standardization Administration of China plans to further develop and improve standards for conservation and comprehensive utilization of natural resources in the following areas: energy, water, wood and land conservation, development of renewable energy, the comprehensive utilization of mineral resources, recovery, recycling and reuse of scrap materials and clean production.[61]

Energy production and consumption

In 2011, China produced 70% of its energy from coal, emitted more carbon dioxide than the next two largest emitters combined (United States and India) and emissions had been increasing by 10% a year.[62]

In 2011, China produced 6% of its energy from hydroelectric, <1% from nuclear, and 1% from other renewable energy sources.[63]

Chinese energy experts estimate that by 2050 the share of electricity from coal will decline to 30%-50%, and that the remaining 50%-70% will come from a combination of oil, natural gas, and renewable energy sources, including hydropower, nuclear power, biomass, solar energy, wind energy, and other renewable energy sources.[64]

In 2007, transportation's share of crude oil consumption in China was approximately 35%, but by 2020 crude oil consumption for transportation will increase to 50% of total crude oil consumption.[65]

According to a study by the Energy Research Institute of the National Development and Reform Commission on the economic circumstances of China's crude oil and chemical industry as of 2007, in recent years China has wasted an average of 400 megatons of coal equivalents per year. In 2006, China consumed 2.46 gigatons coal equivalents, up from 1.4 in 2000. With energy consumption increasing by 10% per year, in the last 5 years total energy consumption exceeded the combined consumption over the previous 20 years. According to Dai Yande, the chairman of the Energy Research Institute of the NDRC, while continued high consumption of energy is unavoidable, China must take steps to change the form of its economic growth and increase substantially the energy efficiency of industry and society. Among other things, China should find new points of economic development that move it away from being the "World's Factory" and improves energy efficiency. It also must avoid unnecessary waste, foster a sustainable economy and encourage renewable energy to reduce its reliance on petrochemical energy resources.[66]

Since June 2006 when Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao visited the Shenhua Group's coal liquefaction project and expressed that coal-to-liquids production was one important part of China's energy security, there have been many new ‘coal to oil' projects announced by many large coal producing provinces and cities. As of the end of 2006, 88 methyl alcohol projects were planned; their total was 48.5 megatons/year. If all of these projects are built, by 2010 output of methyl alcohol will reach 60 megatons/year. This development rush to build coal to oil projects prompted concerns about a new round of wasteful development and the unintended consequences of such rapid development; these include wasteful extraction of coal, excessive water use (this process requires 10 tons of water for every ton of oil produced), and likely increases in the price of coal.[67]

China and Russia are in talks to link their electric power networks so that China can buy power from the Russian Far East to supply Northeast China (Dongbei). The benefits for China of importing power from neighboring countries include conserving domestic resources, lowering energy consumption, lessening China's dependence on imported oil (80%-90% of which must be shipped through unsafe waters) and reducing pollution discharge. China already has begun to build a 1 MV high-tension demonstration project and an 800 kV direct power transmission project; after 2010 China will have a long-distance high-tension, high-capacity line for international transmission. China also is considering connecting its power transmission lines with Mongolia and several former Soviet states that border China; specialists predict that by the year 2020 more than 4 PWh of power will be transmitted to China from neighboring states. In that year China is expected to produce 250 megatons of crude oil and be required to import approximately 350 megatons of crude oil, a reliance on exports of 60%. If China is able to import 620 TWh of power from neighbors, it will be able to reduce crude oil imports by 100 megatons. By importing electricity China will not only reduce its dependence on imported crude oil, but also will enhance energy security by diversifying its foreign energy sources, making China less vulnerable to disruptions in supply.[68]

In 2006 a total of 2.8344 PWh of electricity was generated in China from an installed base of 622 GW of power generating capacity; in 2006 alone an additional 105 GW of installed capacity came on line in China.[69] Experts estimate that another 100 GW of newly installed electric power generating capacity will again come on-line in 2007, but that 2006 probably was the high-water mark for electric power capacity development in China.[70]

See also

China

- Wind power in China

- Solar power in China

- Geothermal power in China

- Bioenergy in China

- List of power stations in China

- List of offshore wind farms in China

- Automotive industry in China

- Climate change in China

- Electric vehicle industry in China

- Energy policy of China

- Pollution in China

- Three Gorges Dam

Global

- Renewable energy in Asia

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA)

- World energy resources and consumption

- Renewable energy commercialization

- The Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century(REN21)

- Hydrogen economy

- Global warming

- Greenhouse effect

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- Renewable energy legislation and incentives

- Sustainable energy

- Renewable energy by country

References

- "IEA - Report". www.iea.org. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- Dong, Wenjuan; Ye, Qi (18 May 2018). "Utility of renewable energy in China's low-carbon transition". Brookings. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- Deng, Haifeng and Farah, Paolo Davide and Wang, Anna, China's Role and Contribution in the Global Governance of Climate Change: Institutional Adjustments for Carbon Tax Introduction, Collection and Management in China (24 November 2015). Journal of World Energy Law and Business, Oxford University Press, Volume 8, Issue 6, December 2015. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2695612

- Andrews-Speed, Philip (November 2014). "China's Energy Policymaking Processes and Their Consequences". The National Bureau of Asian Research Energy Security Report. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- John A. Mathews & Hao Tan (10 September 2014). "Economics: Manufacture renewables to build energy security". Nature.

- Reuters Editorial (21 January 2016). "China's solar capacity overtakes Germany in 2015, industry data show". Reuters.

- "Chinese solar capacity outshone Germany's in 2015". businessgreen.com.

- N, Sushma U. "India is beating China in the race to build massive solar power projects". Quartz. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- Frankfurt School – UNEP Collaborating Centre for Climate & Sustainable Energy Finance (2018). Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment 2018. Available online at: https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/unep/documents/global-trends-renewable-energy-investment-2018

- Approval status of CDM projects in China(up to 16 June 2006)

- China's National Climate Change Programme, 2007-06-04

- "China To Launch Massive Hydropower Construction in 21st Century". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "Global Wind Atlas". Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- "China's Big Push for Renewable Energy: Scientific American". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "The 13th Five-Year-Plan for Wind Power" (PDF). National Energy Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2017.

- "China's wind-power boom to outpace nuclear by 2020". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "China's Wind Power Industry: Blowing Past Expectations". Renewable Energy World. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- REN21 (2009). Renewables Global Status Report: 2009 Update Archived 12 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine p. 16.

- "China tops the world in clean energy production". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "Wind power becomes Europe's fastest growing energy source". the Guardian. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- Bradsher, Keith (30 January 2010). "China Leading Global Race to Make Clean Energy". The New York Times.

- "China blasts through wind energy target". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- 中国风电装机容量连续5年增长100%

- "Norway's Equinor to cooperate with China's CPIH in offshore wind". Reuters. 25 September 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- "Global Solar Atlas". Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- 颜培. "Size key to success in solar panel sector". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "China is utterly and totally dominating solar panels". FORTUNE. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- "China Leading Global Race to Make Clean Energy". The New York Times. 31 January 2010.

- "India's solar mission: How it is harnessing unlimited energy". EcoSeed. 23 September 2009.

- "Anwell Produces its First Thin Film Solar Panel". Solarbuzz. 7 September 2009.

- "First Solar to Team With Ordos City on Major Solar Power Plant in China Desert". First Solar. 8 September 2009. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- "China pioneers in renewable energy". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- Chinese development status of bioethanol and biodiesel

- World Economic Outlook Update, 25 July 2007

- Sector looks set to grow to be pillar of economy

- Ashden Awards. "Daxu, stoves burning crop waste". Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- Ashden Awards. "Shaanxi Mothers, biogas for cooking and lighting". Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- Geothermal Resources in China

- "国家能源部雏形初现 折射中国能源格局混乱". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- 网易. "国家能源委员会成立 温家宝任主任". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "US Replaces China as Top Clean Energy Investor". Environmental Leader.

- "中华人民共和国可再生能源法(全文)". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "可再生能源十二五规划初稿拟定 水电核电领衔新能源". Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "金太阳示范工程财政补助资金管理暂行办法(全文)". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- 发改委关于促进风电产业发展实施意见

- "中华人民共和国可再生能源法". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "Agriculture Law of the People's Republic of China (Order of the President No.81)". Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Energy Conservation Law of China

- The Renewable Energy Law of the People's Republic of China Archived 15 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Environmental Regulations in China

- Source: UNFCCC: .

- Source: UNFCCC website, statistics section: .

- "Xantrex and Shanghai Electric Supply China Renewable Energy Market". Renewable Energy World. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "Bosch Rexroth revs up capacity". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "China's Coal Industry: The Waste Has Us Gasping". TreeHugger. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- China coal industry unlikely to open up completely to foreign owners - AACI

- "China to share disaster expertise". SciDev.Net. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "China jumps into e-waste initiative". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- Borenstein, Seth (12 April 2013). "China's Carbon Emissions Directly Linked to Rise In Daily Temperature Spikes, Study Finds". The Huffingtion Post. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- "China - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)".

- Energy and Advanced Coal Utilization Strategy in China

- "China's Global Hunt for Energy". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "Improving Chinese energy efficiency". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "China Coal Chemical Industry Report, 2006". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "China-Russia Energy Cooperation" (PDF). Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "Office of Fossil Energy - Department of Energy". Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "Power Generation -- U.S. Commercial Service China". Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Renewable energy in China. |

- China Renewable Energy Society

- China Renewable Energy Information Network

- China Renewable Energy Scale-up Program

- The China Sustainable Energy Program of the Energy Foundation

- Professional Association for China's Environment (PACE)

- China Energy Group of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

- China New Energy Network (CNE)

- Energy Research Institute of the NDRC

- Renewable Energy Development Project Office of the NDRC

- China Renewable Energy Development Center of the NDRC

- China Renewable Energy Industries Association

- Are the Chinese Working To Curb Their Emissions? (China's Alternative Energy Revitalization Plan).

- Renewable Energy Policy in China: Overview of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (US NREL)

- China Watch of the Worldwatch Institute and Beijing-based Global Environmental Institute (GEI)

- China Renewable Energy and Sustainable Development Report: September 2007

- China Embraces The Development Of Renewable Energy

- Approaches to using renewable energy in rural areas of China

- Energy (R)evolution: A Sustainable China Energy Outlook (Greenpeace China report)

- The China International CleanTech Suppliers Conference

- REN21 Renewables 2016 Global Status - global statistics

- China Energy Statistical Yearbook 2016