Religiosity

Religiosity is difficult to define, but different scholars have seen this concept as broadly about religious orientations and involvement. It includes experiential, ritualistic, ideological, intellectual, consequential, creedal, communal, doctrinal, moral, and cultural dimensions.[1] Sociologists of religion have observed that the people's beliefs, sense of belonging, and behavior often are not congruent with an individual's actual religious beliefs since there is much diversity in how one can be religious or not.[2] Multiple problems exist in measuring religiosity. For instance, variables such as church attendance produce different results when different methods are used such as traditional surveys vs time use surveys.[3]

Diversity in an individuals' beliefs, affiliations, and behaviors

Decades of anthropological, sociological, and psychological research have established that "religious congruence" (the assumption that religious beliefs and values are tightly integrated in an individual's mind or that religious practices and behaviors follow directly from religious beliefs or that religious beliefs are chronologically linear and stable across different contexts) is actually rare. People’s religious ideas are fragmented, loosely connected, and context-dependent; like in all other domains of culture and in life. The beliefs, affiliations, and behaviors of any individual are complex activities that have many sources including culture. As examples of religious incongruence he notes, "Observant Jews may not believe what they say in their Sabbath prayers. Christian ministers may not believe in God. And people who regularly dance for rain don’t do it in the dry season."[2]

Demographic studies often show wide diversity of religious beliefs, belonging, and practices in both religious and non-religious populations. For instance, out of Americans who are not religious and not seeking religion: 68% believe in God, 12% are atheists, 17% are agnostics; also, in terms of self-identification of religiosity 18% consider themselves religious, 37% consider themselves as spiritual but not religious, and 42% considers themselves as neither spiritual nor religious; and 21% pray every day and 24% pray once a month.[4][5][6] Global studies on religion also show diversity.[7]

Components

Numerous studies have explored the different components of human religiosity (Brink, 1993; Hill & Hood 1999). What most have found is that there are multiple dimensions (they often employ factor analysis). For instance, Cornwall, Albrecht, Cunningham and Pitcher (1986) identify six dimensions of religiosity based on the understanding that there are at least three components to religious behavior: knowing (cognition in the mind), feeling (effect to the spirit), and doing (behavior of the body). For each of these components of religiosity, there were two cross classifications resulting in the six dimensions:[10]

- Cognition

- traditional orthodoxy

- particularistic orthodoxy

- Effect

- Palpable

- Tangible

- Behavior

- religious behavior

- religious participation

Other researchers have found different dimensions, ranging generally from four to twelve components. What most measures of religiosity find is that there is at least some distinction between religious doctrine, religious practice, and spirituality.

For example, one can accept the truthfulness of the Bible (belief dimension), but never attend a church or even belong to an organized religion (practice dimension). Another example is an individual who does not hold orthodox Christian doctrines (belief dimension), but does attend a charismatic worship service (practice dimension) in order to develop his/her sense of oneness with the divine (spirituality dimension).

An individual could disavow all doctrines associated with organized religions (belief dimension), not affiliate with an organized religion or attend religious services (practice dimension), and at the same time be strongly committed to a higher power and feel that the connection with that higher power is ultimately relevant (spirituality dimension). These are explanatory examples of the broadest dimensions of religiosity and may not be reflected in specific religiosity measures.

Most dimensions of religiosity are correlated, meaning people who often attend church services (practice dimension) are also likely to score highly on the belief and spirituality dimensions. But individuals do not have to score high on all dimensions or low on all dimensions; their scores can vary by dimension.

Sociologists have differed over the exact number of components of religiosity. Charles Glock's five-dimensional approach (Glock, 1972: 39) was among the first of its kind in the field of sociology of religion.[11] Other sociologists adapted Glock's list to include additional components (see for example, a six component measure by Mervin F. Verbit).[12][13][14]

Contributions

Genes and environment

The contributions of genes and environment to religiosity have been quantified in studies of twins (Bouchard et al., 1999; Kirk et al., 1999) and sociological studies of welfare, availability, and legal regulations [16] (state religions, etc.).

Koenig et al. (2005) report that the contribution of genes to variation in religiosity (called heritability) increases from 12% to 44% and the contribution of shared (family) effects decreases from 56% to 18% between adolescence and adulthood.[17]

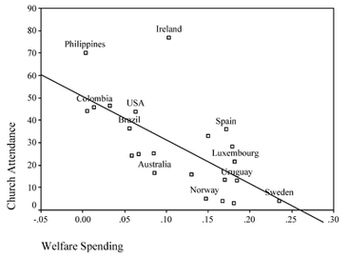

A market-based theory of religious choice and governmental regulation of religion have been the dominant theories used to explain variations of religiosity between societies. However, Gill and Lundsgaarde (2004) [15] documented a much stronger correlation between welfare state spending and religiosity. See "Welfare spending vs Church attendance" diagram on the right.

Just-world hypothesis

Studies have found belief in a just world to be correlated with aspects of religiousness.[18][19]

Risk-aversion

Several studies have discovered a positive correlation between the degree of religiousness and risk aversion.[20][21]

See also

Demographics:

- Importance of religion by country

- Religiosity and intelligence

- Religion and happiness

- Religiosity and education

References

- Holdcroft, Barbara (September 2006). "What is Religiosity?". Catholic Education: A Journal of Inquiry and Practice. 10 (1): 89–103.

- Chaves, Mark (March 2010). "SSSR Presidential Address Rain Dances in the Dry Season: Overcoming the Religious Congruence Fallacy". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 49 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2009.01489.x.

- Rossi, Maurizio; Scappini, Ettore (June 2014). "Church Attendance, Problems of Measurement, and Interpreting Indicators: A Study of Religious Practice in the United States, 1975-2010". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 53 (2): 249–267. doi:10.1111/jssr.12115. ISSN 0021-8294.

- "American Nones: The Profile of the No Religion Population" (PDF). American Religious Identification Survey. 2008. Retrieved 2014-01-30.

- "Religion and the Unaffiliated". "Nones" on the Rise. Pew Research Center: Religion & Public Life. October 9, 2012.

- "Most of the Religiously Unaffiliated Still Keep Belief in God". Pew Research Center. November 15, 2012.

- "The Global Religious Landscape". Pew Research Center. 2012-12-18.

- Crabtree, Steve. "Religiosity Highest in World's Poorest Nations". Gallup. Retrieved 27 May 2015. (in which numbers have been rounded)

- GALLUP WorldView - data accessed on 17 January 2009

- Cornwall; Albrecht; Cunningham; Pitcher (1986). "The Dimensions of Religiosity: A Conceptual Model with an Empirical Test". Review of Religious Research. 27 (3): 226–244. doi:10.2307/3511418. JSTOR 3511418.

- Glock, C. Y. (1972) ‘On the Study of Religious Commitment’ in J. E. Faulkner (ed.) Religion’s Influence in Contemporary Society, Readings in the Sociology of Religion, Ohio: Charles E. Merril: 38-56.

- Verbit, M. F. (1970). "The components and dimensions of religious behavior: Toward a reconceptualization of religiosity". American mosaic. 24: 39.

- Küçükcan, T (2010). "Multidimensional Approach to Religion: a way of looking at religious phenomena". Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies. 4 (10): 60–70.

- http://www.eskieserler.com/dosyalar/mpdf%20(1135).pdf

- Gill, Anthony; Erik Lundsgaarde (2004). "State Welfare Spending and Religiosity" (PDF). Comparative Political Studies. 16 (4): 399–436. doi:10.1177/1043463104046694.

- Nolan, P., & Lenski, G. E. (2010). Human societies: Introduction to macrosociology. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publisher.

- Koenig, L. B.; McGue, M.; Krueger, R. F.; Bouchard Jr, T. J. (2005). "Genetic and environmental influences on religiousness: findings for retrospective and current religiousness ratings". Journal of Personality. 73: 471–488. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00316.x.

- Begue, L (2002). "Beliefs in justice and faith in people: just world, religiosity and interpersonal trust". Personality and Individual Differences. 32 (3): 375–382. doi:10.1016/s0191-8869(00)00224-5.

- Kurst, J.; Bjorck, J.; Tan, S. (2000). "Causal attributions for uncontrollable negative events". Journal of Psychology and Christianity. 19: 47–60.

- Noussair, Charles; Stefan T. Trautmann; Gijs van de Kuilen; Nathanael Vellekoop (2013). "Risk aversion and religion" (PDF). Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 47 (2): 165–183. doi:10.1007/s11166-013-9174-8..

- Adhikari, Binay; Anup Agrawal (2016). "Does local religiosity matter for bank risk-taking?". Journal of Corporate Finance. 38: 272–293. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2016.01.009..

External links

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Religiosity |

- Bouchard, TJ Jr; McGue, M; Lykken, D; Tellegen, A (Jun 1999). "Intrinsic and extrinsic religiousness: genetic and environmental influences and personality correlates". Twin Res. 2 (2): 88–98. doi:10.1375/twin.2.2.88.

- Brink, T.L. 1993. Religiosity: measurement. in Survey of Social Science: Psychology, Frank N. Magill, Ed., Pasadena, CA: Salem Press, 1993, pp. 2096–2102.

- Cornwall, M.; Albrecht, S.L.; Cunningham, P.H.; Pitcher, B.L. (1986). "The dimensions of religiosity: A conceptual model with an empirical test". Review of Religious Research. 27: 226–244. doi:10.2307/3511418.

- Hill, Peter C. and Hood, Ralph W. Jr. 1999. Measures of Religiosity. Birmingham, Alabama: Religious Education Press. ISBN 0-89135-106-X

- Kirk, KM; Eaves, LJ; Martin, NG (Jun 1999). "Self-transcendence as a measure of spirituality in a sample of older Australian twins". Twin Res. 2 (2): 81–7. doi:10.1375/twin.2.2.81. PMID 10480742.

- Winter, T. Kaprio J; Viken, RJ; Karvonen, S; Rose, RJ. (Jun 1999). "Individual differences in adolescent religiosity in Finland: familial effects are modified by sex and region of residence". Twin Res. 2 (2): 108–14. doi:10.1375/136905299320565979. PMID 10480745.

.svg.png)