Religion in Spain

The major religion in Spain has been Catholic Christianity since the Reconquista, with a small minority of other Christian and non-Christian religions and high levels of secularization as of 2020. The Pew Research Center ranked Spain as the 16th out of 34 European countries in levels of religiosity, which is lower than Italy, Portugal and Poland, but much higher than the United Kingdom and the Nordic countries.[2] There is no official religion and religious freedom is protected: the Spanish Constitution of 1978 abolished Catholicism as the official state religion, while recognizing the role it plays in Spanish society.[3]

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Spain |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

|

Mythology and folklore

|

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

|

| Art |

| Literature |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Media

|

| Sport |

|

Monuments |

|

Symbols |

|

Catholicism has been present in the Iberian Peninsula since Roman times.[4][5] The Spanish Empire spread it to the Philippine islands and Latin America, which are now predominantly Catholic countries.[6][7][8] However, since the end of the Francoist dictatorship practical secularization has grown strongly.[9][10][11][12][13] Only 3% of Spaniards consider religion as one of their three most important values, lower than the 5% European average.[14]

A Survey published in 2019 by the Pew Research Center found that 54% of Spaniards had a favorable view of Muslims, while 76% had a favorable view about Jews.[15] Spain has been seen as a graveyard for Protestant missionaries:[16] only 1% of the population of Spain is Protestant[17] and 92% of Spain's 8,131 villages do not have any evangelical protestant church.[18][19]

According to the Spanish Center for Sociological Research, 68.3% of Spanish citizens self-identify as Catholics, (46.8% define themselves as not practising, while 21.5% as practising), 2.6% as followers of other faiths (including Islam, Protestant Christianity, Buddhism etc.), and 27.9% identify as Atheists (12.5%), agnostics (7.3%) or non-believers (8.1%) as of October 2019.[1] Most Spaniards do not participate regularly in religious worship. This same study shows that of the Spaniards who identify themselves as religious, 31.9% never attend mass, 30% barely ever attend mass, 16% attend mass a few times a year, 7.1% two or three times per month, 11.5% every Sunday and holidays, and 2% multiple times per week.[1]

Although a majority of Spaniards self-identify as Catholics, many younger generations ignore the Church's moral doctrines on issues such as pre-marital sex, sexual orientation, marriage or contraception.[10][11][20][21] The total number of parish priests shrank from 24,300 in 1975 to 18,500 in 2018, with an average age of 65.5 years.[22][23][24] By contrast, some expressions of popular religiosity still thrive, often linked to local festivals.

Attitudes

[Asked only to Catholics or believers in another religion] How often do you attend mass or other religious services, except for those related to ceremonies of social nature, such as weddings, communions or funerals? (October 2019 CIS survey; N=12,512)[1]

While Catholicism is still the largest religion in Spain, most Spaniards—and especially the younger—choose not to follow the Catholic teachings in morals, politics or sexuality, and do not attend Mass regularly.[10][25][26] Irreligiosity, including agnosticism and atheism, enjoys social prestige in line with the general Western European secularization.[12][13][25][16][27]

Culture wars in Spain are far more related to politics than religion, and the huge unpopularity of typically religion-related issues like creationism prevent them from being used in such conflicts. Revivalist efforts by the Catholic Church and other creeds have not had any significant success out of their previous sphere of influence.[26][16] According to the Eurobarometer 83 (2015), only 3% of Spaniards consider religion as one of their three most important values, just like in 2008 and even lower than the 5% European average.[14][28] And according to the 2005 Eurobarometer Poll:[29]

- 59% of Spaniards responded that "they believe there is a God."

- 21% answered that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force".

- 18% answered that "they do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God, or life force."

Evidence of the liberal turn in contemporary Spain can be seen in the widespread support for the legalization of same-sex marriage in Spain—over 70% of Spaniards supported gay marriage in 2004 according to a study by the Centre for Sociological Research.[30] Indeed, in June 2005 a bill was passed by 187 votes to 147 to allow gay marriage, making Spain the third country in the European Union to allow same-sex couples to marry. This vote was split along conservative-liberal lines, with Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) and other left-leaning parties supporting the measure and the center-to-right People's Party (PP) against it. However, when the Popular Party came into power in 2011, the law was not revoked or modified. Changes to the divorce laws to make the process quicker and to eliminate the need for a guilty party have also been popular. Abortion, contraception and emergency contraception are legal and readily available on par with Western European standards.

Christianity

Catholicism

Eastern Orthodoxy

Spain is not a traditionally Orthodox country, as after the Great Schism of 1054 the Spanish Christians (at that time controlling the northern half of the Iberian Peninsula) remained in the Catholic sphere of influence.

The number of Orthodox adherents in the country began to increase in the early 1990s, when Spain experienced an influx of migrant workers from Eastern Europe. The dominant nationality among Spanish Orthodox adherents is Romanian (as many as 0.7 million people), with Bulgarians, Russians, Ukrainians, Moldovans, and others bringing the total to about 1.0 million.

Protestantism

Protestantism in Spain has been boosted by immigration, but remains a small testimonial force among native Spaniards (1%). Spain has been seen as a graveyard for foreign missionaries (meaning lack of success) among Evangelical Protestants.[16] Protestant churches claim to have about 1,200,000 members.[31][32]

Other

Irreligion and Atheism

Irreligion in Spain is a phenomenon that exists at least since the 17th century.[33] Atheism, agnosticism and freethinking became relatively popular (although the majority of the society was still very religious) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. During the Spanish civil war irreligious people were repressed by the Francoist side, while religion was largely abolished among the republicans. During the Francoist dictatorship period (1939-1975) irreligion was not tolerated, following the national-catholic ideology of the regime. Irreligious people could not be public workers or express their thoughts openly. After the Spanish democratic transition (1975-1982), restrictions on irreligion were lifted.[34] In the last decades religious practice has fallen dramatically and atheism and agnosticism have grown in popularity, with over 14 million people (30.3% of the population as of January 2020)[35] having no religion.[36]

Popular religion

However, some expressions of popular religiosity still thrive, often linked to Christian festivals and local patron saints. World-famous examples include the Holy Week in Seville, the Romería de El Rocío in Huelva or the Mystery Play of Elche, while the Sanfermines in Pamplona and the Falles of Valencia have mostly lost their original religious nature. The continuing success of these festivals is the result of a mix of religious, cultural, social and economic factors including sincere devotion, local or family traditions, non-religious fiesta and partying, perceived beauty, cultural significance, territorial identity, meeting friends and relatives, increased sales and a massive influx of tourists to the largest ones. The Pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela is not so popular among Spaniards but it attracts many visitors. Most if not all cities and towns celebrate a patron saint's festival, no matter how small or known, which often includes processions, Mass and the like but whose actual religious following is variable and sometimes merely nominal.[37]

Another trend among Spanish believers is syncretism, often defined as religión a la carta.[38] In religion à la carte, people mix popular Roman Catholic beliefs and traditions with their own worldview and/or esoteric, self-help, New Age or philosophical borrowings they like, resulting in a unique personal 'soft' spirituality without any possible church.[39] These people typically self-define themselves as Catholics, but they only attend church for christenings, funerals or weddings and are not actual followers.

Islam

The recent waves of immigration, especially during and after the 1990s, have led to an increasing number of Muslims and Protestants. Nowadays, Islam is the second largest religion, but far behind Roman Catholicism and irreligion. A study made by Unión de comunidades islámicas de España showed that there were almost 1,900,000 inhabitants of Muslim background living in Spain in 2016 (4% of the total population).[40] The vast majority was composed of immigrants and descendants originating from Morocco and other North African/Arab countries. Almost 780,000 of them had Spanish nationality.[40]

Judaism

Jews in Spain account for less than 0.2% of the population, mostly in Barcelona, Madrid and Murcia.[41]

Minor religions

Besides various varieties of Christianity, Islam, Judaism and the non-religious, Spain also has small groups of Hindus, Buddhists, Pagans, Taoists, and Bahá'ís.

Hinduism

Hinduism first arrived in Spain by Sindhi immigrants through British colony of Gibraltar in the early 20th century[42]. There are about 40,000[43]-50,000 Hindus in Spain, about 25,000 from India, 5,000 from Eastern Europe and Latin America and 10,000 Spanish. There are also small communities of Hindus from Nepal (around 200) and Bangladesh (around 500).[44]

There are also about 40 Hindu temples/worship-places in Spain. The first Hindu temple in Ceuta city was completed in 2007. There are ISKCON Krishna Temples in Barcelona, Madrid, Malaga, Tenerife and Brihuega along with a Krishna restaurant in Barcelona.[45] Some of Hinduism's shared teaching with Buddhism like reincarnation or karma, have partially syncretized with the cultural mainstream via New Age-style movements.

Buddhism

Buddhism didn't arrive in Spain until the late 20th century. According to an estimation, there are around 65,000 followers and an indeterminate number of sympathizers. However, some of its teachings, like reincarnation or karma, have partially syncretized with the cultural mainstream via New Age-style movements.

Paganism

Paganism draws a minority in Spain. The most visible pagan religions are forms of Germanic Heathenism (Spanish: Etenismo), Celtic paganism (and Druidry) and Wicca. Spanish Heathen groups include the Odinist Community of Spain–Ásatrú, which identifies as both Odinist and Ásatrú, the Asatru Lore Vanatru Assembly, the Gotland Forn Sed and Circulo Asatrú Tradición Hispánica, of which four, the first one is officially registered by the State; Celtist or Druidic groups include the Dun Ailline Druid Brotherhood (Hermandad Druida Dun Ailline) and the Fintan Druidic Order, both registered.[46] Amongst the Wiccan groups, two have been granted official registration: the Spanish Wiccan Association (Asociación Wicca España) and the Celtiberian Wicca (Wicca Tradición Celtíbera).[47]

Galicia is a center of Druidry (Galician: Druidaria) due to its strong Celtic heritage; the Pan-Galician Druidic Order (Galician: Irmandade Druídica Galaica) is specific to Galicia. In the Basque Country, traditional Basque Gentility (Basque: Jentiltasuna) and Sorginkery (Basque: Sorginkeria), Basque witchcraft, have been revived and have ties with Basque nationalism. Sorginkoba Elkartea is a Basque Neopagan organisation active in the Basque countries.

Taoism

Taoism has a presence in Spain, especially in Catalonia. Among Spanish people, it was introduced by the Chinese master Tian Chengyang in the 2000s, leading to the foundation of the Catalan Taoist Association (Asociación de Taoísmo de Cataluña) and the opening of the Temple of Purity and Silence (Templo de la Pureza y el Silencio) in Barcelona, both in 2001. The association has planned to expand the Temple of Purity and Silence as a traditional Chinese Taoist templar complex, the first Taoist temple of this kind in Europe.[48]

A further Taoist temple was opened in 2014 by the Chinese community of Barcelona, led by Taoist priest Liu Zemin, a 21st-generation descendant of poet, soldier and prophet Liu Bo Wen (1311-1375). The temple, located in the district of Sant Martí and inaugurated with the presence of the People's Republic of China consul Qu Chengwu, enshrines 28 deities of the province of China where most of the Chinese in Barcelona come from.[49][50]

Specific beliefs

A 2008 poll by the Obradoiro de Socioloxia[51] yielded the following results:[52]

| Sex | Age | Education | Religion | Total | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belief | Male | Female | 18–29 | 30–44 | 45–59 | 60+ | Elementary school | High school | College & higher | Practicing Catholic | Non-practicing Catholic | No religion | Yes | No | Unsure | N/A |

| % answering Yes: | Total percentage: | |||||||||||||||

| Existence of God | 45 | 61 | 45 | 50 | 49 | 68 | 61 | 48 | 47 | 89 | 54 | 0 | 53 | 23 | 23 | 1 |

| Divine creation ex nihilo | 26 | 42 | 26 | 28 | 30 | 51 | 43 | 29 | 26 | 68 | 26 | 3 | 34 | 47 | 17 | 2 |

| Adam and Eve | 21 | 37 | 20 | 25 | 23 | 40 | 22 | 19 | 23 | 58 | 24 | 2 | 29 | 53 | 17 | 1 |

| Historicity of Jesus | 70 | 76 | 63 | 65 | 71 | 80 | 70 | 77 | 72 | 94 | 68 | 65 | 73 | 13 | 13 | 1 |

| Jesus son of God | 40 | 54 | 38 | 41 | 45 | 63 | 57 | 41 | 39 | 85 | 46 | 0 | 47 | 25 | 23 | 2 |

| Virgin birth of Jesus | 35 | 46 | 26 | 35 | 37 | 63 | 55 | 31 | 29 | 81 | 35 | 0 | 41 | 41 | 16 | 2 |

| Three wise men visited Jesus | 40 | 51 | 37 | 43 | 45 | 56 | 52 | 42 | 38 | 71 | 47 | 11 | 45 | 35 | 18 | 2 |

| Resurrection of Jesus | 35 | 50 | 32 | 38 | 36 | 63 | 52 | 37 | 33 | 83 | 38 | 0 | 43 | 38 | 17 | 2 |

| Miracles | 35 | 46 | 40 | 42 | 36 | 44 | 42 | 43 | 35 | 67 | 36 | 14 | 41 | 44 | 14 | 1 |

| Afterlife | 30 | 50 | 34 | 41 | 33 | 52 | 45 | 33 | 41 | 72 | 34 | 14 | 41 | 36 | 22 | 1 |

| Reincarnation | 12 | 17 | 23 | 18 | 10 | 7 | 14 | 15 | 14 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 14 | 68 | 16 | 2 |

| Communication with the dead | 13 | 15 | 24 | 19 | 9 | 5 | 12 | 18 | 12 | 13 | 17 | 8 | 14 | 72 | 13 | 1 |

| Heaven | 30 | 43 | 32 | 33 | 27 | 53 | 44 | 35 | 28 | 71 | 31 | 2 | 37 | 48 | 14 | 1 |

| Hell | 24 | 30 | 27 | 26 | 19 | 35 | 20 | 29 | 20 | 49 | 24 | 0 | 27 | 56 | 15 | 1 |

| Angels | 25 | 39 | 26 | 32 | 27 | 42 | 36 | 30 | 28 | n/d | n/d | n/d | 32 | 52 | 15 | 1 |

| The Devil | 24 | 35 | 27 | 29 | 21 | 39 | 35 | 28 | 23 | 55 | 26 | 3 | 29 | 56 | 13 | 1 |

| Malevolent sorcery | 14 | 23 | 20 | 21 | 21 | 13 | 19 | 22 | 14 | 22 | 19 | 9 | 19 | 70 | 10 | 1 |

| Evil eye | 19 | 24 | 27 | 23 | 22 | 13 | 24 | 26 | 11 | 24 | 25 | 9 | 21 | 69 | 8 | 1 |

| Divination of the future | 14 | 16 | 20 | 18 | 15 | 8 | 14 | 20 | 10 | 14 | 16 | 10 | 15 | 72 | 12 | 1 |

| Astrology | 21 | 27 | 30 | 23 | 23 | 21 | 28 | 22 | 20 | 25 | 26 | 18 | 24 | 63 | 11 | 2 |

| UFOs | 25 | 22 | 28 | 32 | 20 | 13 | 19 | 26 | 27 | 19 | 25 | 23 | 23 | 61 | 14 | 1 |

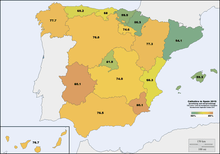

Regional Data

Large studies carried out by the Center for Sociological Research (Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas) in September-October 2012 and September-October 2019 discovered information relating to the rates of religious self-identification across Spain's various autonomous communities. A study carried out by the same institution in October 2019 showed that the percentage of Catholics has decreased overall, from 72.9% to 68.3%, in a period of seven years.[53][54]

| Region | Catholic Practicing and non-practicing |

Other | Unaffiliated

(Atheism/Agnosticism) |

Unanswered | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2019 | 2012 | 2019 | 2012 | 2019 | 2012 | 2019 | ||

| 85.0 | 80.1 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 13.9 | 17.9 | 0.3 | 0 | [57] | |

| 81.2 | 80.1 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 17 | 18 | 0.7 | 0.3 | [58] | |

| 82.2 | 77.7 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 16.6 | 19.4 | 0.7 | 1.7 | [59] | |

| 82.4 | 77.3 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 15.2 | 16.6 | 1.2 | 4.0 | [60] | |

| 79.4 | 76.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 17.1 | 20.3 | 1.8 | 1.3 | [61] | |

| 84.9 | 76.7 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 12.3 | 20.2 | 1.0 | 0.3 | [62] | |

| 78.8 | 76.5 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 18.6 | 21.2 | 0.8 | 0.5 | [63] | |

| 74.0 | 74.6 | 2.6 | 1.1 | 23.2 | 22.9 | 0.3 | 1.4 | [64] | |

| 81.1 | 74.0 | 2.1 | 2 | 15.2 | 23.3 | 1.6 | 0.8 | [65] | |

| 72.9 | 68.3 | 2.3 | 3.2 | 23.0 | 25.4 | 1.7 | 1.2 | [66] | |

| 74.3 | 68.0 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 21.8 | 29 | 2.0 | 2.3 | [67] | |

| 75.0 | 66.3 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 21.3 | 30.5 | 0.9 | 1.1 | [68] | |

| 76.5 | 65.2 | 0.5 | 3.3 | 21.5 | 30.8 | 1.5 | 0.8 | [69] | |

| 46.3 | 65.0 | 37.5 | 20 | 12.1 | 15.0 | 4.3 | 0 | [70] | |

| 62.9 | 61.9 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 28.4 | 31.8 | 4.9 | 1.7 | [71] | |

| 68.0 | 60.0 | 28.3 | 36.7 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 0.5 | 0 | [72] | |

| 58.6 | 59.9 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 36.9 | 36.7 | 2.5 | 0.9 | [73] | |

| 68.7 | 59.3 | 1.8 | 4.3 | 28.0 | 33.7 | 1.5 | 2.8 | [74] | |

| 65.7 | 56.3 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 32.6 | 41.0 | 1.5 | 0.3 | ||

| 60.7 | 54.1 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 34.2 | 41.0 | 1.9 | 1.7 | [76] | |

History

Spain, it has been observed, is a nation-state born out of religious struggle mainly between Catholicism and Islam, but also against Judaism (and, to a lesser extent, Protestantism). The Reconquista against Al Andalus (ending in 1492), the establishment of the Spanish Inquisition (1478) and the expulsion of Jews (1492) were highly relevant in the union of Castile and Aragon under the Catholic Monarchs Isabel and Fernando (1492), followed by the persecution and eventual expulsion of the Moriscos in 1609. The Counter-Reformation (1563–1648) was especially strong in Spain and the Inquisition was not definitively abolished until 1834, thus keeping Islam, Judaism, Protestantism and parts of the Enlightenment at bay for most of its history.

Antiquity and late Antiquity

Before Christianity, there were multiple beliefs in the Iberian Peninsula including local Iberian, Celtiberian and Celtic religions, as well as the Greco-Roman religion.

According to a medieval legend, the apostle James was the first to spread Christianity in the Roman Iberian Peninsula. There is no factual evidence of this but he later became the patron saint of Spaniards and Portuguese, originating the Way of St James. According to Romans 15, Paul the Apostle also intended to visit Hispania; tradition has that he did and founded the Diocese of Écija, but there is no evidence of this either. Other later myths include the Seven Apostolic Men.

There is some archaeological evidence of Christianity slowly penetrating the Peninsula from Rome and Roman Mauretania via major cities and ports, especially Tarragona, since the early 2nd century. The Paleo-Christian Necropolis of Tarragona, with 2,050 discovered tombs, dates back to the second half of the 3rd century. Saints like Eulalia of Mérida or Barcelona and many others are believed to have been martyred during the Decian or Diocletianic Persecutions (3rd–early 4th centuries). Bishops like Basílides of Astorga, Marcial of Mérida or the influential Hosius of Corduba were active in the same period.

Theodosius I issued decrees that effectively made Nicene Christianity the official state church of the Roman Empire.,[77][78] This Christianity was already an early form of Catholicism.

As Rome declined, Germanic tribes invaded most of the lands of the former empire. In the years following 410 the Visigoths—who had converted to Arian Christianity around 360—occupied what is now Spain and Portugal. The Visigothic Kingdom established its capital in Toledo; it reached its high point during the reign of Leovigild (568-586). Visigothic rule led to a brief expansion of Arianism in Spain, however the native population remained staunchly Catholic. In 587 Reccared, the Visigothic king at Toledo, converted to Catholicism and launched a movement to unify doctrine. The Council of Lerida in 546 constrained the clergy and extended the power of law over them under the blessings of Rome. The multiple Councils of Toledo definitively established what would be later known as the Catholic Church in Spain and contributed to define Catholicism elsewhere.

Middle Ages

By the early 8th century, the Visigothic kingdom had fragmented and the fragments were in disarray, bankrupt and willing to accept external help to fight each other. In 711 an Arab raiding party led by Tariq ibn-Ziyad crossed the Strait of Gibraltar, then defeated the Visigothic king Roderic at the Battle of Guadalete. Tariq's commander, Musa bin Nusair, then landed with substantial reinforcements. Taking advantage of the Visigoths' infighting, by 718 the Muslims dominated most of the peninsula, establishing Islamic rule until 1492.

During this period the number of Muslims increased greatly through the migration of Arabs and Berbers, and the conversion of local Christians to Islam (known as Muladis or Muwalladun) with the latter forming the majority of the Islamic-ruled area by the end of the 10th century. Most Christians who remained adopted Arabic culture, and these Arabized Christians became known as Mozarabs. While under the status of dhimmis the Christian and Jewish subjects had to pay higher taxes than Muslims and could not hold positions of power over Muslims.

The era of Muslim rule before 1055 is often considered a "Golden Age" for the Jews as Jewish intellectual and spiritual life flourished in Spain.[79] Only in the northern fringes of the peninsula did Christians remain under Christian rule. Here they established the great pilgrimage centre of Santiago de Compostela.

In the Middle Ages, Spain saw a slow Christian re-conquest of Muslim territories. In 1147, when the Almohads took control of Muslim Andalusian territories, they reversed the earlier tolerant attitude and treated Christians harshly. Faced with the choice of death, conversion, or emigration, many Jews and Christians emigrated.[80] Christianity provided the cultural and religious cement that helped bind together those who rose up against the Moors and sought to drive them out. Christianity and the Catholic Church helped shape the re-establishment of European rule over Iberia.

After centuries of the Reconquista, in which Christian Spaniards fought to drive out the Muslims, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile established the Spanish Inquisition in 1478, a religious purge of Muslim and Jewish thought and practice, from the Iberian Peninsula. Granada, the last Muslim redoubt, was eventually reconquered on January 2, 1492, 781 years after Tariq's first landing.

Modern period

In the Early Modern Period, Spain saw itself as the bulwark of Catholicism and doctrinal purity. Spain carried Catholicism to the New World and to the Philippines, but the Spanish kings insisted on independence from papal "interference"—bishops in the Spanish domains were forbidden to report to the Pope except through the Spanish crown. In the 18th century, Spanish rulers drew further from the papacy, banishing the Jesuits from their empire in 1767. The Spanish authorities abolished the Inquisition in the 1830s, but even after that, religious freedom was denied in practice, if not in theory.

Concordat of 1851

Catholicism became the state religion in 1851, when the Spanish government signed a Concordat with the Holy See that committed Madrid to pay the salaries of the clergy and to subsidize other expenses of the Roman Catholic Church as a compensation for the seizure of church property in the Desamortización de Mendizábal of 1835-1837. This pact was renounced in 1931, when the secular constitution of the Second Spanish Republic imposed a series of anticlerical measures that threatened the Church's hegemony in Spain, provoking the Church's support for the Francisco Franco uprising five years later.[81] In the ensuing Civil War, alleged communists and anarchists in Republican areas killed about 7,000 priests, the majority murdered between July and December 1936. Over four thousand were diocesan priests, as well as 13 bishops, and 2,365 male regulars or religious priests.[82][83][84]

Second Spanish Republic

On 9 December 1931, the Spanish Constitution of 1931 established a secular state and freedom of religion in the Second Spanish Republic. It would remain in effect until 1 April 1939.

Francoist Spain

_-_Fondo_Car-Kutxa_Fototeka.jpg)

The advent of the Franco regime saw the restoration of the church's privileges under a totalitarian system known as National Catholicism. During the Franco years, Roman Catholicism was the only religion to have legal status; other worship services could not be advertised, and no other religion could own property or publish books. The Government not only continued to pay priests' salaries and to subsidize the Church, it also assisted in the reconstruction of church buildings damaged by the war. Laws were passed abolishing divorce and civil marriages as well as banning abortion and the sale of contraceptives. Homosexuality and all other forms of sexual permissiveness were also banned. Catholic religious instruction was mandatory, even in public schools. Franco secured in return the right to name Roman Catholic bishops in Spain, as well as veto power over appointments of clergy down to the parish priest level.

In 1953 this close cooperation was formalized in a new Concordat with the Vatican that granted the church an extraordinary set of privileges: mandatory canonical marriages for all Catholics; exemption from government taxation; subsidies for new building construction; censorship of materials the Church deemed offensive; the right to establish universities, to operate radio stations, and to publish newspapers and magazines; protection from police intrusion into church properties; and exemption of military service.[85]

The proclamation of the Second Vatican Council in favor of religious freedom in 1965 provided more rights to other religious denominations in Spain. In the late 1960s, the Vatican attempted to reform the Church in Spain by appointing interim, or acting, bishops, thereby circumventing Franco's stranglehold on the country's clergy. Many young priests, under foreign influence, became worker priests and participated in anti-regime agitation. Many of them ended as leftist politicians, with some imprisoned in the Concordat prison reserved for priest prisoners. In 1966, the Franco regime passed a law that freed other religions from many of the earlier restrictions, but the law also reaffirmed the privileges of the Catholic Church. Any attempt to revise the 1953 Concordat met Franco's rigid resistance.[85]

Separation of church and state since 1978

In 1976, however, King Juan Carlos de Borbon unilaterally renounced the right to name the bishops; later that year, Madrid and the Vatican signed a new accord that restored to the church its right to name bishops, and the Church agreed to a revised Concordat that entailed a gradual financial separation of church and state. Church property not used for religious purposes was henceforth to be subject to taxation, and over a period of years the Church's reliance on state subsidies was to be gradually reduced. The timetable for this reduction was not adhered to, however, and the church continued to receive the public subsidy through 1987 (US$110 million in that year alone).[85]

It took the new 1978 Spanish Constitution to confirm the right of Spaniards to religious freedom and to begin the process of disestablishing Catholicism as the state religion. The drafters of the Constitution tried to deal with the intense controversy surrounding state support of the Church, but they were not entirely successful. The initial draft of the Constitution did not even mention the Church, which was included almost as an afterthought and only after intense pressure from the church's leadership. Article 16 disestablishes Roman Catholicism as the official religion and provides that religious liberty for non-Catholics is a state-protected legal right, thereby replacing the policy of limited toleration of non-Catholic religious practices. The article further states, however, that: "The public authorities shall take the religious beliefs of Spanish society into account and shall maintain the consequent relations of cooperation with the Catholic Church and the other confessions." In addition, Article 27 also aroused controversy by appearing to pledge continuing government subsidies for private, Church-affiliated schools. These schools were sharply criticized by Spanish Socialists for having created and perpetuated a class-based, separate, and unequal school system. The Constitution, however, includes no affirmation that the majority of Spaniards are Catholics or that the state should take into account the teachings of Catholicism.[85] The Constitution declares Spain a "non-confessional" state, however it is not a laïque (secular) state like France or Mexico.

Government financial aid to the Catholic Church was a difficult and contentious issue. The Church argued that, in return for the subsidy, the state had received the social, health, and educational services of tens of thousands of priests and nuns who fulfilled vital functions that the state itself could not have performed at that time. Nevertheless, the revised Concordat was supposed to replace direct state aid to the church with a scheme that would allow taxpayers to designate a certain portion of their taxes to be diverted directly to the Church. Through 1985, taxpayers were allowed to deduct up to 10 percent from their taxable income for donations to the Catholic Church. Partly because of the protests against this arrangement from representatives of Spain's other religious groups and even from some Catholics, the tax laws were changed in 2007 so that taxpayers could choose between giving 0.52 percent of their income tax to the church and allocating it to the government's welfare and culture budgets. For three years, the government would continue to give the Church a gradually reduced subsidy, but after that the church would have to subsist on its own resources. The government would continue, however, its program of subsidizing Catholic schools, which in 1987 cost the Spanish taxpayers about US$300 million exclusive of the salaries of teachers, which were paid directly by the Ministry of Education and Science.[85]

In a population of about 39 million at the beginning of Transition (begun in November 1975), the number of non-Catholics was probably no more than 300,000. About 290,000 of these were of other Christian faiths, including several Protestant denominations, Jehovah's Witnesses, and Mormons. The number of Jews in Spain was estimated at about 13,000 in the Murcia Jewish community. More than 19 out of every 20 Spaniards were baptized Catholics; about 60 percent of them attended Mass; about 30 percent of the baptized Catholics did so regularly, although this figure declined to about 20 percent in the larger cities. In 1979, about 97 percent of all marriages were performed according to the Catholic rite. A 1982 report by the church claimed that 82 percent of all children born the preceding year had been baptized in the church.[85]

Nevertheless, there were forces at work bringing about fundamental changes in the place of the church in society. One such force was the improvement in the economic fortunes of the great majority of Spaniards, making society more materialistic and less religious. Another force was the massive shift in population from farm and village to the growing urban centers, where the church had less influence over the values of its members. These changes were transforming the way Spaniards defined their religious identity.[85]

Being a Catholic in Spain had less and less to do with regular attendance at Mass and more to do with the routine observance of important rituals such as baptism, marriage, and burial of the dead. A 1980 survey revealed that, although 82 percent of Spaniards were believers in Catholicism, very few considered themselves to be very good practitioners of the faith. In the case of the youth of the country, even smaller percentages believed themselves to be "very good" or "practicing" Catholics.[85]

In contrast to an earlier era, when rejection of the church went along with education, in the late 1980s studies showed that the more educated a person was, the more likely he or she was to be a practicing Catholic. This new acceptance of the church was due partly to the church's new self-restraint in politics. In a significant change from the pre-Civil War era, the church had accepted the need for the separation of religion and the state, and it had even discouraged the creation of a Christian Democratic party in the country.[85]

.jpg)

The traditional links between the political right and the church no longer dictated political preferences; in the 1982 general election, more than half of the country's practicing Catholics voted for the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party. Although the Socialist leadership professed agnosticism, according to surveys between 40 and 45 percent of the party's rank-and-file members held religious beliefs, and more than 70 percent of these professed to be Catholics. Among those entering the party after Franco's death, about half considered themselves Catholic.[85]

One important indicator of the changes taking place in the role of the church was the reduction in the number of Spaniards in Holy Orders. In 1984 the country had more than 22,000 parish priests, nearly 10,000 ordained monks, and nearly 75,000 nuns. These numbers concealed a troubling reality, however. More than 70 percent of the diocesan clergy was between the ages of 35 and 65; the average age of the clergy in 1982 was 49 years. At the upper end of the age range, the low numbers reflected the impact of the Civil War, in which more than 4,000 parish priests died. At the lower end, the scarcity of younger priests reflected the general crisis in vocations throughout the world, which began to be felt in the 1960s. Its effects were felt very acutely in Spain. The crisis was seen in the decline in the number of young men joining the priesthood and in the increase in the number of priests leaving Holy Orders. The number of seminarians in Spain fell from more than 9,000 in the 1950s to only 1,500 in 1979, even though it rose slightly in 1982 to about 1,700.[85] In 2008, there were just 1,221 students in these theological schools.[90]

Changes in the social meaning of religious vocations were perhaps part of the problem; having a priest in the family no longer seemed to spark the kind of pride that family members would have felt in the past. The principal reason in most cases, though, was the church's continued ban on marriage for priests. Previously, the crisis was not particularly serious because of the age distribution of the clergy. As the twentieth century neared an end, however, a serious imbalance appeared between those entering the priesthood and those leaving it. The effects of this crisis were already visible in the decline in the number of parish priests in Spain—from 23,620 in 1979 to just over 22,000 by 1983[85] and 19,307 in 2005.[23] New ordinations also dropped 19% from 241 in 1998 to 196 in 2008, with all-time record lows of 168 priests out of 45 million Spaniards taking their vows in 2007.[90][91][92] The number of nuns shrank 6.9% to 54,160 in the period 2000-2005 as well.[23][93] On the August 21, 2005, Evans David Gliwitzki became the first Catholic priest to get married in Spain.

Another sign of the church's declining role in Spanish life was the diminishing importance of the controversial secular religious institute Opus Dei (Work of God). Opus Dei, a worldwide lay religious body, did not adhere to any particular political philosophy. Its founder, Jose Maria Escriva de Balaguer y Albas, stated that the organization was nonpolitical. The organization was founded in 1928 as a reaction to the increasing secularization of Spain's universities, and higher education continued to be one of the institute's foremost priorities. Despite its public commitment to a nonpolitical stance, Opus Dei members rose to occupy key positions in the Franco régime, especially in the field of economic policy-making in the late 1950s and the early 1960s. Opus Dei members dominated the group of liberal technocrats who engineered the opening of Spain's autarchic economy after 1957. After the 1973 assassination of Prime Minister Luis Carrero Blanco (often rumored to be an Opus Dei member), however, the influence of the institute declined sharply. The secrecy of the order and its activities and the power of its myth helped it maintain its strong position of influence in Spain; but there was little doubt that, compared with the 1950s and the 1960s, Opus Dei had fallen from being one of the country's chief political organizations to being simply one among many such groups competing for power in an open and pluralist society.[85]

21st century

An important number of Latin American immigrants, who are usually strong Catholic practitioners, have helped the Catholic Church to recover part of the attendance that regular Masses (Sunday Mass) used to have in the sixties and seventies and that was lost in the eighties among native Spaniards.

Since 2003, the involvement of the Catholic Church in political affairs, through special groups such as Opus Dei, the Neocatechumenal Way or the Legion of Christ, especially personated through important politicians in the right-wing People's Party, has increased again. Old and new media, which are property of the Church, such as the COPE radio network or 13 TV, have also contributed to this new involvement in politics by their own admission.[94][95] The Church is no longer seen as a neutral and independent institution in political affairs and it is generally aligned with the opinion and politics of the People's Party. This implication has had, as a consequence, a renewed criticism from important sectors of the population (especially the majority of left-wing voters) against the Church and the way in which it is economically sustained by the State. While by 2017-2018 the Church was slowly backpedaling, the damage is potentially long-lasting among the younger generations who had not experienced it personally to such a degree.

The total number of parish priests shrank from 24,300 in 1975 to 18,500 in 2018 when the average age was 65.5 years.[22] The number of nuns dropped by 44.5% to 32,270 between 2000 and 2016; most of them are old.[23][24] By contrast, some expressions of popular religiosity still thrive, often linked to local festivals, and about 68.5% of the population self-defined themselves as Catholics in 2018, but just 39.8% of them (27.3% of the total population) attend Mass monthly or more often.[53] Despite the arrival of large numbers of Catholic, Orthodox, Muslim and Protestant immigrants, irreligion continues to be the fastest growing demographic as of 2018.[96]

See also

- Spanish society after the democratic transition

- Religion in France

- Religion in Portugal

- Christianity in Spain

- Roman Catholicism in Spain

- Opus Dei in Spain

- Palmarian Church

- Protestantism in Spain

- Eastern Orthodoxy in Spain

- Roman Catholicism in Spain

- Islam in Spain

- Judaism in Spain

- Irreligion in Spain

- Bahá'í Faith in Spain

- Hinduism in Spain

References

- "Macrobarómetro de octubre de 2019" (PDF) (in Spanish). Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. p. 37. Retrieved 23 June 2020. The question was "¿Cómo se define Ud. en materia religiosa: católico/a practicante, católico/a no practicante, creyente de otra religión, agnóstico/a, indiferente o no creyente, o ateo/a?", the weight used was "PESOCCAA" which reflects the population sizes of the Autonomous communities of Spain.

- How do European countries differ in religious commitment? Use our interactive map to find out. Pew Research.

- "Spanish Constitution". Sections 14, 16 & 27.3, Constitution of 29 December 1978 (PDF). Retrieved 5 March 2018.

No religion shall have a state character. The public authorities shall take into account the religious beliefs of Spanish society and shall consequently maintain appropriate cooperation relations with the Catholic Church and other confessions.

- The National Catholic Almanac. St. Anthony's Guild. 1956.

- Gannon, Martin J.; Pillai, Rajnandini (2015). Understanding Global Cultures: Metaphorical Journeys Through 34 Nations, Clusters of Nations, Continents, and Diversity. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781483340067.

- Laicidad and Religious Diversity in Latin America. Springer. 2016. p. 10. ISBN 9783319447452.

- Cornelio, Jayeel Serrano (2016). Being Catholic in the Contemporary Philippines: Young People Reinterpreting Religion. Routledge. ISBN 9781317621966.

- Tarver Ph.D., H. Micheal; Slape, Emily (2016). The Spanish Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 198. ISBN 9781610694223.

- -Jofré, Rosa Bruno (2019). Educationalization and Its Complexities: Religion, Politics, and Technology. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781487505349.

- Morel, Sandrine (2017-02-01). "La sécularisation express des jeunes Espagnols" [The express secularization of the Spanish youth] (in French). Le Monde. Retrieved 2018-03-28.

- "España experimenta retroceso en catolicismo - El Mundo - Mundo Cristiano" (in Spanish). CBN.com. 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2015-05-29.

- Loewenberg, Samuel (2005-06-26). "As Spaniards Lose Their Religion, Church Leaders Struggle to Hold On". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- Pingree, Geoff (2004-10-01). "Secular drive challenges Spain's Catholic identity". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- "Eurobarometer 83 - Values of Europeans / Spring 2015" (PDF). May 2015. p. 56. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- "European Public Opinion Three Decades After the Fall of Communism — 6. Minority groups". Pew Research Center. 14 October 2019. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- MacHarg, Kenneth D. "Spain's Awakening:Is revival around the corner for Spain?". Latin American Mission. Archived from the original on 2008-10-23. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- "Global Christianity" (PDF). Pew Research Center. December 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-01. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- "92% dos 8 mil vilarejos na Espanha não têm igrejas evangélicas".

- "Spain: 10 million live in towns without evangelical presence".

- Tarvainen, Sinikka (2004-09-26). "Reforms anger Spanish church". Dawn International. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- "Zapatero accused of rejecting religion". Worldwide Religious News. 2004-10-15. Archived from the original on 2008-10-23. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- "La edad media del clero español es de 65 años y medio". Infocatólica. 2018-03-01. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

- "Estadísticas de la Iglesia en España, 2005" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-20. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- "Cae un 3,5% el número de religiosos en España hasta los 42.921, durante el Año de la Vida Consagrada". La Vanguardia. 2016-02-01. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

- Abernethy, Bobby (2006-07-07). "Catholicism In Spain". PBS. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- Sciolino, Elaine (2005-04-19). "Europeans Fast Falling Away From Church". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- "Spain". International Fellowship of Evangelical Students. Archived from the original on 2008-10-23. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- "Eurobarometer 69 - Values of Europeans" (PDF). November 2008. p. 16. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- "Eurobarometer on Social Values, Science and technology 2005" (PDF). p. 9. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- "·CIS·Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas·Página de inicio". www.cis.es. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- "Información general - Datos estadísticos" [General information - Statistical data] (in Spanish). Federation of Evangelical Religious Entities of Spain. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011.

- "Protestants call for 'equal treatment'". El Pais. December 10, 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- Andreu Navarra Ordoño: El ateísmo. La aventura de pensar libremente en España. Editorial Cátedra, Madrid, 2016.

- Calvo, Vera Gutiérrez; Romero, José Manuel (2013-12-05). "España aconfesional y católica". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (January 2020). "Avance de resultados del estudio 3271 - Barómetro de enero 2020" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 47. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Embid, Julio. "España ha dejado de ser católica practicante". eldiario.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- "Jóvenes, ateos y cofrades" (in Spanish). El País. 2018-03-30. Retrieved 2018-04-08.

- Segurola, Santiago (21 September 2016). "Religión a la carta" [Religion à la carte]. El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- Red Iberoamericana de Estudio de las Sectas (3 April 2013). "Monseñor Munilla: "hoy se llevan el sincretismo y el esoterismo como espiritualidad"". Infocatólica (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- EP (2016-04-10). "Los musulmanes aumentan en España en 300.000 en cinco años". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- "European Jewish Congress - Spain". Archived from the original on 2006-03-01.

- https://www.hinduismtoday.com/modules/smartsection/item.php?itemid=5458

- https://www.yogaenred.com/2016/06/23/presentacion-de-la-federacion-hindu-de-espana/

- https://www.hinduismtoday.com/modules/smartsection/item.php?itemid=5458

- "Hare Krishna Temples Around the World". Stephen-knapp.com. Retrieved 2012-01-22.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-07-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-06-29. Retrieved 2013-07-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-06-12. Retrieved 2013-07-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "S'ha inaugurat un temple taoista a Barcelona" Archived 2017-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de Governació, Administracions Públiques i Habitatge. 29/04/2014. Retrieved 06/05/2017.

- "Así funciona el primer templo taoísta de Barcelona". La Vanguardia, 23/04/2014. Retrieved 06/05/2017.

- Zárraga, José Luis de (26 December 2008). "La fe española hace aguas". publico.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- Cantó, Antonio. "El estado de la religión en España" (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (November 2018). "Barómetro de noviembre de 2018" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 21. Retrieved 5 December 2018. The question was "¿Cómo se define Ud. en materia religiosa: católico/a, creyente de otra religión, no creyente o ateo/a?"

- "Apostatar en España, ¿trámite o vía crucis?". eldiario.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-12-21.

- http://www.lavanguardia.com/vangdata/20150402/54429637154/interactivo-creencias-y-practicas-religiosas-en-espana.html

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos" (in Spanish). p. 77. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Región de Murcia (aut.)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 22. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Extremadura (aut.)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 21. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Galicia (aut.)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 24. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Aragón (aut.)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 24. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Castilla y León (aut.)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 24. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Canarias (aut.)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 23. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Andalucía (aut.)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 23. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, La Rioja (aut.)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 21. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Castilla - La Mancha (aut.)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 24. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos" (in Spanish). p. 160. Retrieved 17 December 2019. The question was "¿Cómo se define Ud. en materia religiosa: católico/a practicante, católico/a no practicante, creyente de otra religión, agnóstico/a, indiferente o no creyente, o ateo/a?", the weight used was "PESOCCAA" which reflects the population sizes of the Autonomous communities of Spain.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Cantabria (aut.)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 21. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Comunidad Valenciana (aut.)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 25. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Principado de Asturias (aut.)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 21. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Ciudad Autónoma de Melilla" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 20. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Comunidad de Madrid (aut.)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 23. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Ciudad Autónoma de Ceuta" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 20. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, País Vasco (aut.)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 23. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Islas Baleares" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 23. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Cataluña (aut.)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 24. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Cf. decree, infra.

- "Edict of Thessalonica": See Codex Theodosianus XVI.1.2

- Rebecca Weiner. "Sephardim". Jewish Virtual Library.

- The Almohads Archived 2009-02-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Text used in this cited section originally came from: Spain Country Study from the Library of Congress Country Studies project.

- Michael Burleigh, Sacred Causes (New York: Harper Collins, 2007) 132.

- Jose M. Sanchez, The Spanish Civil War as a Religious Tragedy (South Bend: Notre Dame Press, 1987) 9.

- Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War, (London 3rd edition, 1990) 271.

- Solsten, Eric; Meditz, Sandra (1990). Spain: A Country Study. United States Library of Congress; Federal Research Division. p. 115. ISBN 9780160285509. LCCN 90006127.

- "El cardenal Tarancón lo intentó en 1971" (in Spanish). El País. 2007-11-20. Retrieved 2018-04-08.

Sin Tarancón y su grupo de colaboradores, apoyados en todo momento por el papa Pablo VI, la transición desde el nacionalcatolicismo hacia la democracia hubiera sido imposible.

- "La rabia de Tarancón" (in Spanish). El País. 2007-09-13. Retrieved 2018-04-08.

- "El cardenal que hizo llorar a Franco" (in Spanish). El País. 2012-01-22. Retrieved 2018-04-08.

- ""'Miembras' abrió el debate. Y eso vale para luchar por la igualdad"" (in Spanish). El País. 2008-06-29. Retrieved 2018-04-08.

Yo siempre me he declarado agnóstico (...) tengo una visión laica de la sociedad

- "Estadísticas "Día del Seminario" 2009, Conferencia Episcopal Española" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-30. Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- "Acontecimientos Vocacionales, estadística de seminarios mayores 2007. Pastoral Vocacional, Hermandad de Sacerdotes Operarios". Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- "Acontecimientos Vocacionales, estadística de seminarios mayores 2008. Pastoral Vocacional, Hermandad de Sacerdotes Operarios". Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- "Estadísticas de la Iglesia en España, Diócesis de Canarias". Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- "Un informe de la Iglesia califica a 13TV de "culturalmente pobre", afín al PP y para "la tercera edad"" (in Spanish). eldiario.es. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "La Iglesia califica a 13 TV como afín al PP y para "la tercera edad" | Bluper" (in Spanish). bluper.elespanol.com. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "España, cada vez menos católica, cada vez más incrédula y atea". Infocatólica (in Spanish). 2018-02-08. Retrieved 2018-04-08.

Bibliography