Religion in Chile

Religion in Chile is diverse under secular principles, due to the freedom of religion established under the Constitution.

A majority of Chileans believes firmly in the existence of God. 63% of the population profess some branch of Christianity, according to the Encuesta Nacional Bicentenario identifies as Christian, with an estimated 45% of Chileans declaring to be part of the Catholic Church and 18% of Protestant or Evangelical churches. 5% of the population adheres to other religion.[1]

32% of the population declares to be religiously unaffiliated, including atheists, agnostics and people who do not identify with any particular religion. According to a 2017 poll by Latinobarometro, the country has the second highest rate of non-affiliated people in Latin America (only after Uruguay).[2] This number has increased firmly in the last decades, doubling from the 12% recorded in 2006.[1]

Even though Chile has been identified in the past as a conservative country compared with other Latin American societies, the role of religion has decreased and is now one with the less religious influence in the region. Only 27% of Chileans say religion is very important in their lives, according to a 2015 Pew Research Center report,[3] and less than a third of the population participates normally in religious ceremonies (38% of Protestants and 11% of Catholics). Chile is often seen as a low observant Catholic society, differentiating from more observant societies in Latin America like Mexico and Brazil.[4]

Historically, the indigenous peoples in Chile observed different religions before the Spanish conquest in the XVI century. During Spanish occupation and the first century of Chilean independence, the Catholic Church was one of the most powerful institutions in the country. In the late XIX century, liberal policies (the so-called Leyes laicas or "lay laws") started to reduce the influence of the clergy and the promulgation of a new Constitution in 1925 established the separation of church and state.

Demography

Religion in Chile (Encuesta Nacional Bicentenario 2019)[5]

Religion in Chile (CEP 2018)[6]

In the last census in Chile, in the year 2002, indigenous people make up 5 percent (780,000) of the population. 65 percent of indigenous people identify themselves as Catholic, 29 percent as evangelical, and 6 percent as "others." Mapuche communities, constituting 87 percent of indigenous citizens, continue to respect traditional religious leaders (Longkos and Machis), and anecdotal information indicates a high degree of syncretism in worship and traditional healing practices.[7]

Members of the largest religious groups (Catholic, Pentecostal, and other evangelical churches) are numerous in the capital and are also found in other regions of the country. Jewish communities are located in Santiago, Valparaíso, Viña del Mar, Valdivia, Temuco, Concepción, La Serena, and Iquique (although there is no synagogue in Iquique). Mosques are located in Santiago, Iquique, and Coquimbo.[7]

Religious affiliation and practices

Evolution

| Year | Catholic | Protestant/Evangelical | Unaffiliated (None/Atheist/Agnostic) | Other religions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 70% | 14% | 12% | 4% |

| 2007 | 66% | 18% | 14% | 3% |

| 2008 | 67% | 14% | 15% | 4% |

| 2009 | 67% | 16% | 13% | 4% |

| 2010 | 63% | 17% | 17% | 3% |

| 2011 | 63% | 15% | 18% | 4% |

| 2012 | 59% | 18% | 19% | 4% |

| 2013 | 61% | 17% | 19% | 4% |

| 2014 | 59% | 16% | 22% | 3% |

| 2015 | 61% | 16% | 21% | 2% |

| 2016 | 58% | 18% | 20% | 3% |

| 2017 | 59% | 17% | 19% | 4% |

| 2018 | 58% | 16% | 21% | 3% |

| 2019 | 45% | 18% | 32% | 5% |

Importance of religion

According to a 2015 Pew Research Center report, Chileans who say religion is very important in their lives has decreased from 46% in 2007 to 27% in 2015. Twenty percent said religion is "Not at all important."[3][11]

| How important is religion in your life? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Very important | Somewhat important | Not too important | Not at all important | Don't Know/Refused |

| 2007 | 46% | 31% | 11% | 10% | 3% |

| 2013 | 39% | 32% | 18% | 10% | 0% |

| 2015 | 27% | 34% | 17% | 20% | 2% |

| 2017 | 56% | 21% | 11% | 11% | 1% |

Legal and policy framework

The Constitution provides for freedom of religion, and other laws and policies contribute to the generally free practice of religion. The law at all levels protects this right in full against abuse, either by governmental or private actors.[7]

Church and state are officially separate. The 1999 law on religion prohibits religious discrimination; however, the Catholic Church enjoys a privileged status and occasionally receives preferential treatment. Government officials attend Catholic events and also major Protestant and Jewish ceremonies.[7]

The Government observes Christmas, Good Friday, the Feast of the Virgin of Carmen, the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul, the Feast of the Assumption, All Saints' Day, and the Feast of the Immaculate Conception as national holidays.[7]

The law allows any religious group to apply for legal public right status (comprehensive religious nonprofit status). The Ministry of Justice may not refuse to accept a registration petition, although it may object to the petition within 90 days on the grounds that all legal prerequisites for registration have not been satisfied. The petitioner then has 60 days to address objections raised by the Ministry or challenge the Ministry in court. Once a religious entity is registered, the state cannot dissolve it by decree. The semiautonomous Council for the Defense of the State may initiate a judicial review; however, no organization that has registered under the 1999 law has subsequently been deregistered.[7]

In addition, the law allows religious entities to adopt a charter and by-laws suited to a religious organization rather than a private corporation. They may establish affiliates (schools, clubs, and sports organizations) without registering them as separate corporations.

During the period covered by this report 516 religious organizations registered under the 1999 law and gained legal public right status, bringing the total to 1,659 registered religious groups. Publicly subsidized schools are required to offer religious education twice a week through high school; participation is optional (with parental waiver). Religious instruction in public schools is almost exclusively Catholic. Teaching the creed requested by parents is mandatory; however, enforcement is sometimes lax, and religious education in faiths other than Catholicism is often provided privately through Sunday schools and at other venues. Local school administrations decide how funds are spent on religious instruction. Although the Ministry of Education has approved curriculums for 14 other denominations, 92 percent of public schools and 81 percent of private schools offered only Catholic instruction. Parents may homeschool their children or enroll them in private schools for religious reasons.[7]

Religious freedom

The constitution Chile provides for the freedom of religion, although it stipulates that this freedom must be not be “opposed to morals, to good customs or to the public order". It further establishes a separation between church and state, and other laws prohibit religious discrimination.[13]

Religious organizations are not required to register with the government, but may do so to receive tax breaks. Religious groups may appoint chaplains to provide services in hospitals and prisons. Officially registered groups may appoint chaplains for the military.[13] The celebration of a Catholic Mass frequently marks official and public events. If the event is of a military nature, all members of the participating units may be obliged to attend. Membership in the Catholic Church is considered beneficial to a military career.[7]

All schools are required to provide two hours of religious per week, tailored to the religious affiliations of the students. The majority of such courses focus on a Catholic perspective, but the government has approved curricula for 14 different religious groups. Parents may also choose to excuse their children from such classes.[13]

According to Christian Solidarity Worldwide, arsonists attacked Baptist and Catholic churches in the primarily indigenous Mapuche communities in the rural Araucania Region in 2017. According to other sources, the church attacks fit into a pattern of sabotage directed at a wide range of institutions, business interests, and infrastructure in Araucania, and thus may not necessarily have been intended as a religiously-motivated attack. As of the end of 2017, a trial was still pending for the arson suspects, and the regional government verbally committed itself to helping rebuild the churches.[13]

Leaders of the Jewish community have expressed concerns about incidences of antisemitic vandalism and graffiti targeting Jews.[13]

The National Office of Religious Affairs facilitates inter-religious dialogue and promotes tolerance of religious diversity.[13]

Catholicism

Catholic Church Approval (2017)

As with most of Latin America, Catholicism is the main religion in Chile since its introduction during the Spanish colonization of the Americas although their figures have declined signifactively in the last decade. According to latest polls, between 45% and 55% of the population identifies as Catholic.

Catholicism was introduced by priests with the Spanish colonialists in the 16th century. Most of the native population in the northern and central regions was evangelized by 1650. The southern area proved more difficult and Catholicisim settled in the area after the Occupation of the Araucania in the late XIX century. In the 20th century, church expansion was impeded by a shortage of clergy and government attempts to control church administration. Relations between church and state were strained under both Salvador Allende and Augusto Pinochet.

The Catholic Church is one of the largest organizations in the country. There are five archdioceses, 18 dioceses, two territorial prelatures, one apostolic vicariate, one military ordinariate and one personal prelature (Opus Dei). Usually, the archbishop of Santiago acts as the head of the church in the country, although the Holy See is represented officially by the Apostolic Nunciature to Chile.

The Catholic Church is currently one of the principal providers of education (including universities) and health care in the country and is involved in several initiatives to support different charities. However, the support of the Chilean population has decreased in the last decades, especially after diverse cases of sexual abuse by Catholic members have been published. According to a survey conducted in October 2017 by Plaza Publica Cadem, 56% of Chileans disapprove the performance of the Catholic Church in Chile, whilst 32% approve.[14]

Protestantism

Protestants represent 13% of Chilean people. Protestants first arrived in the first half of the nineteenth century, with American missionary David Trumbull[15] and with German immigrants from Protestant parts of Germany, mainly Lutherans. Later came Anglicans, Presbyterians, Baptists, Seventh-day Adventists, Methodists, Pentecostals, and other Protestant Christians.

Seventh-Day Adventist missionaries first arrived in 1895,[16] today there are estimated 126,814 Adventists in Chile.

Latter-day Saints (Mormon)

Early apostle Parley P. Pratt was among the first Mormon missionaries to preach in Chile, landing in Valparaiso in November, 1851, along with Elder Rufus Allen and Phoebe Sopher, one of Pratt's wives, who was pregnant at the time. The mission party was impressed by the Chilean countryside and people. Pratt wrote that the people he met in Chile were “a neat, plain, loving and sociable people; very friendly, frank, and easy to become acquainted with,” but the mission trip met with tragedy when the Pratt's month-old son died in January 1852.[17] Hampered by language difficulties and a lack of literature in the Spanish language (selections of the Book of Mormon were not translated into Spanish until 1875[18]) the missionaries left Chile after four months without having a successful baptism.[17] Pratt used his experience in South America to advise Brigham Young that the success of future missionary efforts would be based on translations of the scriptures.[19]

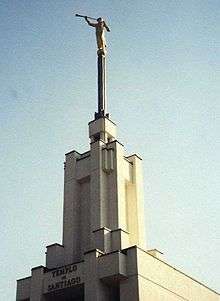

Missionary work in Chile began in earnest in 1956, when the country was made part of the Argentine mission and the first small branch was formed.[20] By 1961, the country had 1,100 members and the Chilean mission was organized. The following three decades saw explosive growth in church membership, with the church membership doubling every two years at its peak.[17] The growth sparked a building boom during these decades. Hundreds of LDS chapels were constructed, capped by the dedication of the Santiago Temple in 1983. Church growth continued in the 1990s, with the country having the greatest growth in LDS membership in South America during the decade. Between 1994 and 1996, 26 new stakes were dedicated in the country.[20] A second temple, in Concepción, was announced in 2009. The Antofagasta Chile Temple, Chile's third temple, was announced on April 7, 2019, by President Russell M. Nelson in his concluding remarks at the Sunday Afternoon Session of General Conference.[21]

Although an average of 12,000 people were baptized annually between 1961 and 1990, membership growth has slowed and the church has a large number of inactive members. According to census data, 0.9% of the population claims to be Mormon, based upon those aged 15 and over who identify themselves as Mormon. The church itself reports that it has 543,628 members in Chile, which is equal to about 3.3% of the population. If accurate, these numbers makes the LDS Church the single largest denomination in Chile after Catholicism.[20] LDS statistics counts everyone baptized, including children age eight or older as well as inactive members. In 2002, the church sent Elder Jeffrey R. Holland, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, to remain in Chile for a year to train leadership and minister to the church, a role typically held by members of the quorums of the seventy.[22]

Jorge F. Zeballos, a former mining engineer, is a Chilean-born LDS General Authority. He was called to the First Quorum of the Seventy in April, 2008.[23] Zeballos is the second Chilean to serve as a General Authority following Eduardo Ayala, who served in the Second Quorum of the Seventy from 1990 to 1995.

Bahá'í Faith

The Bahá'í Faith in Chile begins with references to Chile in Bahá'í literature as early as 1916, with the first Bahá'ís visiting the country as early as 1919. A functioning community wasn't founded in Chile until 1940 with the beginning of the arrival of coordinated pioneers from the United States finding national Chilean converts and achieved an independent national community in 1963. The US government estimated 6000 Bahá'ís in Chile as of 2007[24] though the Association of Religion Data Archives (relying mostly on the World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated some 25,000 Bahá'ís in 2005.[25]

In 2002 this community was picked for the establishment of the first Bahá'í Temple of South America.[26] The Santiago Bahá'í Temple was inaugurated in 2016 in Peñalolén, in the Andean slopes over the city. After its dedication, the temple has become in an important landmark of the city, receiving thousands of visitors every month.

Judaism

The earliest recorded Jew living in Chile was a converso by the name of Rodrigo de Orgonos who came with the expedition of Diego de Almagro in 1535. Conversos were widely persecuted until Chile gained independence from Spain in 1818. Even after independence, it was not until 1865 that a special law permitted non-Catholics to practice their religion in private homes and establish private schools.[27] As of the 2012 Chilean census, 16,294 Chilean residents listed their religion as Judaism.[28]

Hinduism

A few Indians had gone to Chile in the 1920s. The others migrated there about 30 years ago, not only from India, but also from Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Nigeria, Panama, the Philippines and Singapore. The Hindu Community in Chile comprises more than 1400 members. Among these, 400 people (90 families) lives in the Capital city Santiago.[29] Most of the Hindus in Chile are Sindhis. There is a Hindu Temple in Punta Arenas which provide services in both Sindhi and Spanish.[30]

Islam

The statistics for Islam in Chile estimate a total Muslim population of 3,196, representing 0.02 percent of the population.

Islam has enjoyed a long history in Chile. Aurelio Díaz Meza's Chronicles of the History of Chile, one man in discoverer Diego de Almagro's expedition, a certain Pedro de Gasco, was a morisco (that is, a Moor from al-Andalus, Spain, who had been obliged to convert from Islam to Roman Catholicism). The first Islamic institution in Chile, the Muslim Union Society (Sociedad Unión Musulmana), was founded on September 25, 1926, at Santiago. The Society of Mutual Aid and Islamic Charity was established the following year, on October 16, 1927. Sources within the Islamic community indicate that at the moment, in Chile, there are 3,000 Muslims, many of whom are native Chileans who, as a result of their conversions, have even changed their names.

Buddhism

Buddhism first came to Chile by way of Japanese residents of Brazil migrating to the country. Though still a relatively small percentage of the population, it has grown significantly since the 1990s with 15 different centers across the country mostly of the Zen and Tibetan schools.

Irreligion

Of the Chilean population, in 2019, 32% are either atheist, agnostic or without religion in particular.[31]

In September 2011, a group of atheists founded the Atheist Society of Chile.[32]

Wicca

According to the TV program Hola Chile on La Red TV channel there are at least 130 Wiccans in the Valparaíso Region.[33]

Sikhism

In 2016, after a four-year process, the religion received a legal status. The religion was introduced to Chile by Yogi Bhajan in the late 20th century.[34]

See also

References

- Centro de Políticas Pública UC (2019). "Encuesta Nacional Bicentenario 2019: Religión" (PDF) (in Spanish).

- "Latinobarómetro 1995 - 2017: El Papa Francisco y la Religión en Chile y América Latina" (PDF) (in Spanish). January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- "Pew Research Center Spring 2015 survey: Importance of Religion" (PDF). pewglobal.org. Pew Research Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-07-05. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Patterson, Eric (2013). Latin America's Neo-Reformation: Religion's Influence on Contemporary Politics. Routledge. ISBN 9781135412845.

- "Encuesta Nacional Bicentenario 2019: Religión"

- "Estudio Nacional de Opinión Pública" (PDF). Centro de Estudios Públicos. October–November 2018.

- "Chile - International Religious Freedom Report 2008". United States Department of State. 2008-09-19.

- "Encuesta Nacional Bicentenario 2017: Religión" (PDF) (in Spanish). encuestabicentenario.uc.cl. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "Encuesta Nacional Bicentenario 2016: Religión" (PDF) (in Spanish). encuestabicentenario.uc.cl. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "Encuesta Nacional Bicentenario 2019: Religión"

- "Q158. How important is religion in your life?" (PNG). Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- Memoria Chilena, Los cementerios en el siglo XIX

- International Religious Freedom Report 2017 § Chile US Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor.

- "Track semanal de Opinión Pública 9 de Octubre 2017 Estudio Nº 195" (PDF). Plaza Pública Cadem. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "Princeton Theological Seminary Library". Libweb.ptsem.edu. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Chile". Adventist Atlas. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- The Biggest Little Mormon Country in the World | Kristina Cordero | The Virginia Quarterly Report

- Stocks, Hugh G. (1992), "Book of Mormon Translations", in Ludlow, Daniel H (ed.), Encyclopedia of Mormonism, New York: Macmillan Publishing, pp. 213–214, ISBN 0-02-879602-0, OCLC 24502140

- "Autobiograph of Parley P. Pratt, 1807-1857". Gordonbanks.com. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Chile: Facts and Statistics", Newsroom, 2020. Retrieved on 22 March 2020.

- Cox, Erin and Ellis, Joshua "Latter-day Saint leaders announce eight new temples", Fox News, 7 April 2019. Retrieved on 22 March 2020.

- "Country information: Chile". Church News. 2010-01-28. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Elder Jorge F. Zeballos", Church News, 2020. Retrieved on 22 March 2020.

- Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (2007-09-14). "International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Chile". State Department. Retrieved 2008-03-08.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Most Baha'i Nations (2005)". QuickLists > Compare Nations > Religions >. The Association of Religion Data Archives. 2005. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- Lamb, Artemus (November 1995). The Beginnings of the Bahá'í Faith in Latin America:Some Remembrances, English Revised and Amplified Edition. 1405 Killarney Drive, West Linn OR, 97068, United States of America: M L VanOrman Enterprises.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Chile: Virtual Jewish History tour". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- Marcos Fuentes T. (2013-09-13). "Censo: Comunidad Judía duda de las cifras sobre sus fieles - Terra Chile". Noticias.terra.cl. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- Chile, Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de (2008-10-09). "Bharat Dadlani: "La comunidad hindú de Chile se siente como en casa" - Programa Asia Pacifico". Observatorio Asiapacifico (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- "Keeping cultures alive: Sindhis and Hindus in Chile". Hindustan Times. 2015-08-02. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- "Encuesta Nacional Bicentenario 2019: Religión"

- http://sociedadatea.cl/sitio/

- Brujas de Valparaíso confiesan que practican la wicca

- "'We will now be protected': Sikhs get legal rights in Chile", Hindustan Times

.png)