Red Flag (magazine)

The Red Flag (Chinese: 红旗; pinyin: Hóngqí) was a theoretical political journal published by the Chinese Communist Party.[1] It was one of the "Two Newspapers and One Magazine"(两报一刊) during the 1960s and 1970s.[2][3] The newspapers were People's Daily and Guangming Daily.[3] People's Liberation Army Daily is also regarded as one of them.[4]

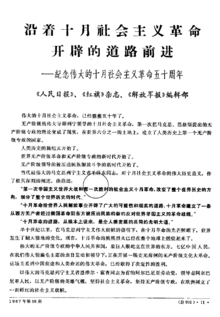

December 1967 issue, ""Advancing along the Road Opened by the October Socialist Revolution" | |

| Categories | Political magazine |

|---|---|

| Frequency | Bi-monthly |

| Publisher | Chinese Communist Party |

| Year founded | 1958 |

| Final issue | July 1988 |

| Country | China |

| Based in | Beijing |

| Language | Chinese |

| ISSN | 0441-4381 |

| OCLC | 1752410 |

History and profile

Red Flag was started during the Great Leap Forward era[2] in 1958.[1][5] The journal was the successor to another journal, Study (Xuexi).[6] Its name was given by Mao Zedong.[1] Chen Boda was the editor of the journal,[6] which served as a crucial media outlet during the Cultural Revolution.[1][7] In 1966 Pol Pot formed a similar magazine with the same name in Cambodia in Khmer language, Tung Krahom, modelled on Red Flag.[8]

During the 1960s Red Flag temporarily ended publication, but was restarted in 1968.[9] The frequency of the journal was monthly between its start in 1958 and 1979.[6] It was published bi-monthly from 1980 to 1988.[6] It covered theoretical arguments supported by the party.[2] In May 1988 Chinese officials announced that the journal would be closed.[10] Finally, it ceased publication in June 1988, and was succeeded by Qiushi, another magazine.[1][5]

References

- "China to Furl Red Flag, Its Maoist Theoretical Journal". Los Angeles Times. Beijing. 1 May 1988. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- Cynthia Leung; Jiening Ruan (4 October 2012). Perspectives on Teaching and Learning Chinese Literacy in China. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 52. ISBN 978-94-007-4821-7. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- Robert B. Kaplan; Richard B. Baldauf (2008). Language Planning and Policy in Asia: Japan, Nepal, Taiwan and Chinese characters. Multilingual Matters. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-84769-095-1. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- “两报一刊”有《光明日报》吗. CNKI.

- "About Qiushi Journal". Qiushi. 19 September 2011. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- Lawrence R. Sullivan (23 May 2007). Historical Dictionary of the People's Republic of China. Scarecrow Press. p. 420. ISBN 978-0-8108-6443-6. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- Kevin Latham (2007). Pop Culture China!: Media, Arts, and Lifestyle. ABC-CLIO. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-85109-582-7. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- Odd Arne Westad; Sophie Quinn-Judge (27 September 2006). The Third Indochina War: Conflict Between China, Vietnam and Cambodia, 1972-79. Routledge. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-134-16776-0. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science, Inc. February 1969. p. 86. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- Roderick MacFarquhar (13 January 1997). The Politics of China: The Eras of Mao and Deng. Cambridge University Press. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-521-58863-8. Retrieved 24 April 2016.