Raspberry Pi

The Raspberry Pi (/paɪ/) is a series of small single-board computers developed in the United Kingdom by the Raspberry Pi Foundation to promote teaching of basic computer science in schools and in developing countries.[13][14][15] The original model became far more popular than anticipated,[16] selling outside its target market for uses such as robotics. It now is widely used even in research projects, such as for weather monitoring[17] because of its low cost and portability. It does not include peripherals (such as keyboards and mice) or cases. However, some accessories have been included in several official and unofficial bundles.[16]

| |

Raspberry Pi 4 Model B | |

| Also known as | RPi |

|---|---|

| Release date |

|

| Introductory price | |

| Operating system | Android FreeBSD Linux NetBSD OpenBSD Plan 9 RISC OS Windows 10 ARM64 Windows 10 IoT Core[4] |

| System-on-chip used | |

| CPU | |

| Memory | |

| Storage | MicroSDHC slot |

| Graphics | |

| Power | 5 V; 3 A (for full power delivery to USB devices)[12] |

| Website | raspberrypi |

After the release of the second board type, the Raspberry Pi Foundation set up a new entity, named Raspberry Pi Trading, and installed Eben Upton as CEO, with the responsibility of developing technology. The Foundation was rededicated as an educational charity for promoting the teaching of basic computer science in schools and developing countries.

The Raspberry Pi is one of the best-selling British computers.[18] As of December 2019, more than thirty million boards have been sold.[19] Most Pis are made in a Sony factory in Pencoed, Wales,[20] while others are made in China and Japan.[21]

Generations

.png)

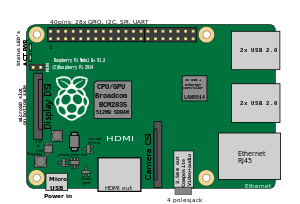

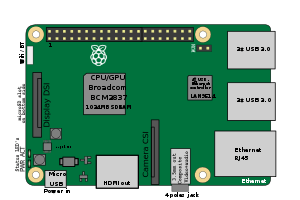

Several generations of Raspberry Pis have been released. All models feature a Broadcom system on a chip (SoC) with an integrated ARM-compatible central processing unit (CPU) and on-chip graphics processing unit (GPU).

Processor speed ranges from 700 MHz to 1.4 GHz for the Pi 3 Model B+ or 1.5 GHz for the Pi 4; on-board memory ranges from 256 MiB to 1 GiB random-access memory (RAM), with up to 8 GiB available on the Pi 4. Secure Digital (SD) cards in MicroSDHC form factor (SDHC on early models) are used to store the operating system and program memory. The boards have one to five USB ports. For video output, HDMI and composite video are supported, with a standard 3.5 mm tip-ring-sleeve jack for audio output. Lower-level output is provided by a number of GPIO pins, which support common protocols like I²C. The B-models have an 8P8C Ethernet port and the Pi 3, Pi 4 and Pi Zero W have on-board Wi-Fi 802.11n and Bluetooth. Prices range from US$5 to $55.

The first generation (Raspberry Pi Model B) was released in February 2012, followed by the simpler and cheaper Model A. In 2014, the Foundation released a board with an improved design, Raspberry Pi Model B+. These boards are approximately credit-card sized and represent the standard mainline form-factor. Improved A+ and B+ models were released a year later. A "Compute Module" was released in April 2014 for embedded applications.

The Raspberry Pi 2, which featured a 900 MHz quad-core ARM Cortex-A7 processor and 1 GiB RAM, was released in February 2015.

A Raspberry Pi Zero with smaller size and reduced input/output (I/O) and general-purpose input/output (GPIO) capabilities was released in November 2015 for US$5. On 28 February 2017, the Raspberry Pi Zero W was launched, a version of the Zero with Wi-Fi and Bluetooth capabilities, for US$10.[22][23] On 12 January 2018, the Raspberry Pi Zero WH was launched, a version of the Zero W with pre-soldered GPIO headers.[24]

Raspberry Pi 3 Model B was released in February 2016 with a 1.2 GHz 64-bit quad core processor, on-board 802.11n Wi-Fi, Bluetooth and USB boot capabilities.[25] On Pi Day 2018, the Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+ was launched with a faster 1.4 GHz processor and a three-times faster gigabit Ethernet (throughput limited to ca. 300 Mbit/s by the internal USB 2.0 connection) or 2.4 / 5 GHz dual-band 802.11ac Wi-Fi (100 Mbit/s).[26] Other features are Power over Ethernet (PoE) (with the add-on PoE HAT), USB boot and network boot (an SD card is no longer required).

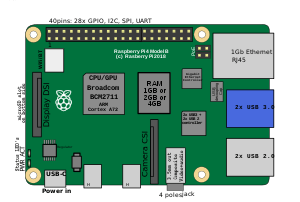

Raspberry Pi 4 Model B was released in June 2019[2] with a 1.5 GHz 64-bit quad core ARM Cortex-A72 processor, on-board 802.11ac Wi-Fi, Bluetooth 5, full gigabit Ethernet (throughput not limited), two USB 2.0 ports, two USB 3.0 ports, and dual-monitor support via a pair of micro HDMI (HDMI Type D) ports for up to 4K resolution . The Pi 4 is also powered via a USB-C port, enabling additional power to be provided to downstream peripherals, when used with an appropriate PSU. The initial Raspberry Pi 4 board has a design flaw where third-party e-marked USB cables, such as those used on Apple MacBooks, incorrectly identify it and refuse to provide power.[27][28] Tom's Hardware tested 14 different cables and found that 11 of them turned on and powered the Pi without issue.[29] The design flaw was fixed in revision 1.2 of the board, released in late 2019.[30]

| Family | Model | Form Factor | Ethernet | Wireless | GPIO | Released | Discontinued |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raspberry Pi | B | Standard[lower-alpha 1] | Yes | No | 26-pin | 2012 | Yes |

| A | No | 2013 | Yes | ||||

| B+ | Yes | 40-pin | 2014 | ||||

| A+ | Compact[lower-alpha 2] | No | 2014 | ||||

| Raspberry Pi 2 | B | Standard[lower-alpha 1] | Yes | No | 2015 | ||

| Raspberry Pi Zero | Zero | Zero[lower-alpha 3] | No | No | 2015 | ||

| W/WH | Yes | 2017 | |||||

| Raspberry Pi 3 | B | Standard[lower-alpha 1] | Yes | Yes | 2016 | ||

| A+ | Compact[lower-alpha 2] | No | 2018 | ||||

| B+ | Standard[lower-alpha 1] | Yes | 2018 | ||||

| Raspberry Pi 4 | B (1 GiB) | Standard[lower-alpha 1] | Yes | Yes | 2019[31] | Yes[1] | |

| B (2 GiB) | |||||||

| B (4 GiB) | |||||||

| B (8 GiB) | 2020 |

- 85.6 mm × 56.5 mm (3.37 in × 2.22 in)

- 65 mm × 56.5 mm (2.56 in × 2.22 in)

- 65 mm × 30 mm (2.6 in × 1.2 in)

Hardware

The Raspberry Pi hardware has evolved through several versions that feature variations in the type of the central processing unit, amount of memory capacity, networking support, and peripheral-device support.

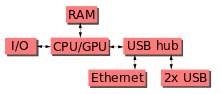

This block diagram describes Model B and B+; Model A, A+, and the Pi Zero are similar, but lack the Ethernet and USB hub components. The Ethernet adapter is internally connected to an additional USB port. In Model A, A+, and the Pi Zero, the USB port is connected directly to the system on a chip (SoC). On the Pi 1 Model B+ and later models the USB/Ethernet chip contains a five-port USB hub, of which four ports are available, while the Pi 1 Model B only provides two. On the Pi Zero, the USB port is also connected directly to the SoC, but it uses a micro USB (OTG) port. Unlike all other Pi models, the 40 pin GPIO connector is omitted on the Pi Zero with solderable through holes only in the pin locations. The Pi Zero WH remedies this.

Processor

All SoCs used in Raspberry Pis are custom-developed under collaboration of Broadcom and Raspberry Pi Foundation.

The Broadcom BCM2835 SoC used in the first generation Raspberry Pi[32] includes a 700 MHz ARM1176JZF-S processor, VideoCore IV graphics processing unit (GPU),[33] and RAM. It has a level 1 (L1) cache of 16 KiB and a level 2 (L2) cache of 128 KiB. The level 2 cache is used primarily by the GPU. The SoC is stacked underneath the RAM chip, so only its edge is visible. The ARM1176JZ(F)-S is the same CPU used in the original iPhone,[34] although at a higher clock rate, and mated with a much faster GPU.

The earlier V1.1 model of the Raspberry Pi 2 used a Broadcom BCM2836 SoC with a 900 MHz 32-bit, quad-core ARM Cortex-A7 processor, with 256 KiB shared L2 cache.[35] The Raspberry Pi 2 V1.2 was upgraded to a Broadcom BCM2837 SoC with a 1.2 GHz 64-bit quad-core ARM Cortex-A53 processor,[36] the same SoC which is used on the Raspberry Pi 3, but underclocked (by default) to the same 900 MHz CPU clock speed as the V1.1. The BCM2836 SoC is no longer in production as of late 2016.

The Raspberry Pi 3 Model B uses a Broadcom BCM2837 SoC with a 1.2 GHz 64-bit quad-core ARM Cortex-A53 processor, with 512 KiB shared L2 cache. The Model A+ and B+ are 1.4 GHz[37][38][39]

The Raspberry Pi 4 uses a Broadcom BCM2711 SoC with a 1.5 GHz 64-bit quad-core ARM Cortex-A72 processor, with 1 MiB shared L2 cache.[40][41] Unlike previous models, which all used a custom interrupt controller poorly suited for virtualisation, the interrupt controller on this SoC is compatible with the ARM Generic Interrupt Controller (GIC) architecture 2.0, providing hardware support for interrupt distribution when using ARM virtualisation capabilities.[42][43]

The Raspberry Pi Zero and Zero W use the same Broadcom BCM2835 SoC as the first generation Raspberry Pi, although now running at 1 GHz CPU clock speed.[44]

Performance

While operating at 700 MHz by default, the first generation Raspberry Pi provided a real-world performance roughly equivalent to 0.041 GFLOPS.[45][46] On the CPU level the performance is similar to a 300 MHz Pentium II of 1997–99. The GPU provides 1 Gpixel/s or 1.5 Gtexel/s of graphics processing or 24 GFLOPS of general purpose computing performance. The graphical capabilities of the Raspberry Pi are roughly equivalent to the performance of the Xbox of 2001.

Raspberry Pi 2 V1.1 included a quad-core Cortex-A7 CPU running at 900 MHz and 1 GiB RAM. It was described as 4–6 times more powerful than its predecessor. The GPU was identical to the original.[35] In parallelised benchmarks, the Raspberry Pi 2 V1.1 could be up to 14 times faster than a Raspberry Pi 1 Model B+.[47]

The Raspberry Pi 3, with a quad-core ARM Cortex-A53 processor, is described as having ten times the performance of a Raspberry Pi 1.[48] Benchmarks showed the Raspberry Pi 3 to be approximately 80% faster than the Raspberry Pi 2 in parallelised tasks.[49]

Overclocking

Most Raspberry Pi systems-on-chip could be overclocked to 800 MHz, and some to 1000 MHz. There are reports the Raspberry Pi 2 can be similarly overclocked, in extreme cases, even to 1500 MHz (discarding all safety features and over-voltage limitations). In the Raspbian Linux distro the overclocking options on boot can be done by a software command running "sudo raspi-config" without voiding the warranty.[50] In those cases the Pi automatically shuts the overclocking down if the chip temperature reaches 85 °C (185 °F), but it is possible to override automatic over-voltage and overclocking settings (voiding the warranty); an appropriately sized heat sink is needed to protect the chip from serious overheating.

Newer versions of the firmware contain the option to choose between five overclock ("turbo") presets that when used, attempt to maximise the performance of the SoC without impairing the lifetime of the board. This is done by monitoring the core temperature of the chip and the CPU load, and dynamically adjusting clock speeds and the core voltage. When the demand is low on the CPU or it is running too hot the performance is throttled, but if the CPU has much to do and the chip's temperature is acceptable, performance is temporarily increased with clock speeds of up to 1 GHz, depending on the board version and on which of the turbo settings is used.

The overclocking modes are:

- none; 700 MHz ARM, 250 MHz core, 400 MHz SDRAM, 0 overvolting

- modest; 800 MHz ARM, 250 MHz core, 400 MHz SDRAM, 0 overvolting,

- medium; 900 MHz ARM, 250 MHz core, 450 MHz SDRAM, 2 overvolting,

- high; 950 MHz ARM, 250 MHz core, 450 MHz SDRAM, 6 overvolting,

- turbo; 1000 MHz ARM, 500 MHz core, 600 MHz SDRAM, 6 overvolting,

- Pi 2; 1000 MHz ARM, 500 MHz core, 500 MHz SDRAM, 2 overvolting,

- Pi 3; 1100 MHz ARM, 550 MHz core, 500 MHz SDRAM, 6 overvolting. In system information the CPU speed appears as 1200 MHz. When idling, speed lowers to 600 MHz.[50][51]

In the highest (turbo) mode the SDRAM clock speed was originally 500 MHz, but this was later changed to 600 MHz because of occasional SD card corruption. Simultaneously, in high mode the core clock speed was lowered from 450 to 250 MHz, and in medium mode from 333 to 250 MHz.

The CPU of the first and second generation Raspberry Pi board did not require cooling with a heat sink or fan, even when overclocked, but the Raspberry Pi 3 may generate more heat when overclocked.[52]

RAM

The early designs of the Raspberry Pi Model A and B boards included only 256 MiB of random access memory (RAM). Of this, the early beta Model B boards allocated 128 MiB to the GPU by default, leaving only 128 MiB for the CPU.[53] On the early 256 MiB releases of models A and B, three different splits were possible. The default split was 192 MiB for the CPU, which should be sufficient for standalone 1080p video decoding, or for simple 3D processing. 224 MiB was for Linux processing only, with only a 1080p framebuffer, and was likely to fail for any video or 3D. 128 MiB was for heavy 3D processing, possibly also with video decoding.[54] In comparison, the Nokia 701 uses 128 MiB for the Broadcom VideoCore IV.[55]

The later Model B with 512 MiB RAM, was released on 15 October 2012 and was initially released with new standard memory split files (arm256_start.elf, arm384_start.elf, arm496_start.elf) with 256 MiB, 384 MiB, and 496 MiB CPU RAM, and with 256 MiB, 128 MiB, and 16 MiB video RAM, respectively. But about one week later, the foundation released a new version of start.elf that could read a new entry in config.txt (gpu_mem=xx) and could dynamically assign an amount of RAM (from 16 to 256 MiB in 8 MiB steps) to the GPU, obsoleting the older method of splitting memory, and a single start.elf worked the same for 256 MiB and 512 MiB Raspberry Pis.[56]

The Raspberry Pi 2 has 1 GiB of RAM. The Raspberry Pi 3 has 1 GiB of RAM in the B and B+ models, and 512 MiB of RAM in the A+ model.[57][58][59] The Raspberry Pi Zero and Zero W have 512 MiB of RAM.

The Raspberry Pi 4 is available with 2, 4 or 8 GiB of RAM.[60] A 1GiB model was originally available at launch in June 2019 but was discontinued in March 2020,[1] and the 8 GiB model was introduced in May 2020.[3]

Networking

The Model A, A+ and Pi Zero have no Ethernet circuitry and are commonly connected to a network using an external user-supplied USB Ethernet or Wi-Fi adapter. On the Model B and B+ the Ethernet port is provided by a built-in USB Ethernet adapter using the SMSC LAN9514 chip.[61] The Raspberry Pi 3 and Pi Zero W (wireless) are equipped with 2.4 GHz WiFi 802.11n (150 Mbit/s) and Bluetooth 4.1 (24 Mbit/s) based on the Broadcom BCM43438 FullMAC chip with no official support for monitor mode but implemented through unofficial firmware patching[62] and the Pi 3 also has a 10/100 Mbit/s Ethernet port. The Raspberry Pi 3B+ features dual-band IEEE 802.11b/g/n/ac WiFi, Bluetooth 4.2, and Gigabit Ethernet (limited to approximately 300 Mbit/s by the USB 2.0 bus between it and the SoC). The Raspberry Pi 4 has full gigabit Ethernet (throughput is not limited as it is not funnelled via the USB chip.)

Special-purpose features

The Pi Zero can be used as a USB device or "USB gadget", plugged into another computer via a USB port on another machine. It can be configured in multiple ways, for example to show up as a serial device or an ethernet device.[63] Although originally requiring software patches, this was added into the mainline Raspbian distribution in May 2016.[63]

The Pi 3 can boot from USB, such as from a flash drive.[64] Because of firmware limitations in other models, the Pi 2B v1.2, 3A+, 3B, and 3B+ are the only boards that can do this.

Peripherals

Although often pre-configured to operate as a headless computer, the Raspberry Pi may also optionally be operated with any generic USB computer keyboard and mouse.[65] It may also be used with USB storage, USB to MIDI converters, and virtually any other device/component with USB capabilities, depending on the installed device drivers in the underlying operating system (many of which are included by default).

Other peripherals can be attached through the various pins and connectors on the surface of the Raspberry Pi.[66]

Video

The video controller can generate standard modern TV resolutions, such as HD and Full HD, and higher or lower monitor resolutions as well as older NTSC or PAL standard CRT TV resolutions. As shipped (i.e., without custom overclocking) it can support the following resolutions: 640×350 EGA; 640×480 VGA; 800×600 SVGA; 1024×768 XGA; 1280×720 720p HDTV; 1280×768 WXGA variant; 1280×800 WXGA variant; 1280×1024 SXGA; 1366×768 WXGA variant; 1400×1050 SXGA+; 1600×1200 UXGA; 1680×1050 WXGA+; 1920×1080 1080p HDTV; 1920×1200 WUXGA.[67]

Higher resolutions, up to 2048×1152, may work[68][69] or even 3840×2160 at 15 Hz (too low a frame rate for convincing video).[70] Allowing the highest resolutions does not imply that the GPU can decode video formats at these resolutions; in fact, the Pis are known to not work reliably for H.265 (at those high resolutions), commonly used for very high resolutions (however, most common formats up to Full HD do work).

Although the Raspberry Pi 3 does not have H.265 decoding hardware, the CPU is more powerful than its predecessors, potentially fast enough to allow the decoding of H.265-encoded videos in software.[71] The GPU in the Raspberry Pi 3 runs at higher clock frequencies of 300 MHz or 400 MHz, compared to previous versions which ran at 250 MHz.[72]

The Raspberry Pis can also generate 576i and 480i composite video signals, as used on old-style (CRT) TV screens and less-expensive monitors through standard connectors – either RCA or 3.5 mm phono connector depending on model. The television signal standards supported are PAL-BGHID, PAL-M, PAL-N, NTSC and NTSC-J.[73]

Lack of real-time clock

None of the Raspberry Pi models have a built-in real-time clock. When booting, the time is either set manually or configured from a state previously saved at shutdown to provide relative consistency for the file system. The Network Time Protocol is used to update the system time when connected to a network.

Connectors

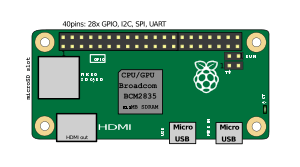

Pi Zero

|

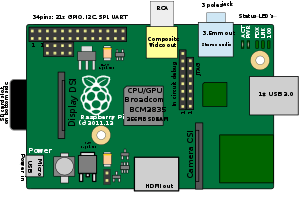

Model A

|

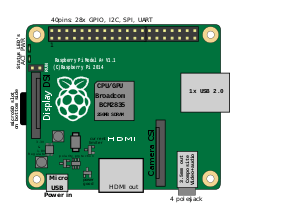

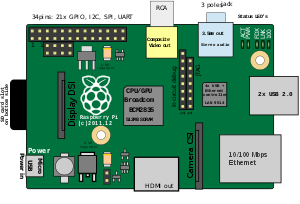

Model B

|

|

General purpose input-output (GPIO) connector

Raspberry Pi 1 Models A+ and B+, Pi 2 Model B, Pi 3 Models A+, B and B+, Pi 4, and Pi Zero, Zero W, and Zero WH GPIO J8 have a 40-pin pinout.[74][75] Raspberry Pi 1 Models A and B have only the first 26 pins.[76][77][78]

In the Pi Zero and Zero W the 40 GPIO pins are unpopulated, having the through-holes exposed for soldering instead. The Zero WH (Wireless + Header) has the header pins preinstalled.

| GPIO# | 2nd func. | Pin# | Pin# | 2nd func. | GPIO# | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +3.3 V | 1 | 2 | +5 V | |||

| 2 | SDA1 (I²C) | 3 | 4 | +5 V | ||

| 3 | SCL1 (I²C) | 5 | 6 | GND | ||

| 4 | GCLK | 7 | 8 | TXD0 (UART) | 14 | |

| GND | 9 | 10 | RXD0 (UART) | 15 | ||

| 17 | GEN0 | 11 | 12 | GEN1 | 18 | |

| 27 | GEN2 | 13 | 14 | GND | ||

| 22 | GEN3 | 15 | 16 | GEN4 | 23 | |

| +3.3 V | 17 | 18 | GEN5 | 24 | ||

| 10 | MOSI (SPI) | 19 | 20 | GND | ||

| 9 | MISO (SPI) | 21 | 22 | GEN6 | 25 | |

| 11 | SCLK (SPI) | 23 | 24 | CE0_N (SPI) | 8 | |

| GND | 25 | 26 | CE1_N (SPI) | 7 | ||

| (Pi 1 Models A and B stop here) | ||||||

| 0 | ID_SD (I²C) | 27 | 28 | ID_SC (I²C) | 1 | |

| 5 | N/A | 29 | 30 | GND | ||

| 6 | N/A | 31 | 32 | 12 | ||

| 13 | N/A | 33 | 34 | GND | ||

| 19 | N/A | 35 | 36 | N/A | 16 | |

| 26 | N/A | 37 | 38 | Digital IN | 20 | |

| GND | 39 | 40 | Digital OUT | 21 | ||

Model B rev. 2 also has a pad (called P5 on the board and P6 on the schematics) of 8 pins offering access to an additional 4 GPIO connections.[79] These GPIO pins were freed when the four board version identification links present in revision 1.0 were removed.[80]

| GPIO# | 2nd func. | Pin# | Pin# | 2nd func. | GPIO# | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +5 V | 1 | 2 | +3.3 V | |||

| 28 | GPIO_GEN7 | 3 | 4 | GPIO_GEN8 | 29 | |

| 30 | GPIO_GEN9 | 5 | 6 | GPIO_GEN10 | 31 | |

| GND | 7 | 8 | GND |

Models A and B provide GPIO access to the ACT status LED using GPIO 16. Models A+ and B+ provide GPIO access to the ACT status LED using GPIO 47, and the power status LED using GPIO 35.

Specifications

| Version | Model A | Model B | Compute Module[lower-alpha 1] | Zero | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPi 1 Model A | RPi 1 Model A+ | RPi 3 Model A+ | RPi 1 Model B | RPi 1 Model B+ | RPi 2 Model B | RPi 2 Model B v1.2 | RPi 3 Model B | RPi 3 Model B+ | RPi 4 Model B | Compute Module 1 | Compute Module 3 | Compute Module 3 Lite | Compute Module 3+ | Compute Module 3+ Lite | RPi Zero PCB v1.2 | RPi Zero PCB v1.3 | RPi Zero W | |

| Release date | Feb 2013[81] | Nov 2014[82] | Nov 2018 | Apr–June 2012 | July 2014[83] | Feb 2015[35] | Oct 2016[84] | Feb 2016[48] | 14 Mar 2018[26] | 24 June 2019[85] 28 May 2020 (8GB)[3] |

Apr 2014[86][87] | Jan 2017[88] | Jan 2019[89] | Nov 2015[8] | May 2016 | 28 Feb 2017 | ||

| Target price (USD) | $25[81] | $20[82] | $25 | $35[90] | $25[91] | $35 | $35/55/75[85][1][3] | $30 (in batches of 100)[92] | $30 | $25 | $30/35/40 | $25 | $5[8] | $10 | ||||

| Instruction set | ARMv6Z (32-bit) | ARMv8 (64-bit) | ARMv6Z (32-bit) | ARMv7-A (32-bit) | ARMv8-A (64/32-bit) | ARMv6Z (32-bit) | ARMv8-A (64/32-bit) | ARMv6Z (32-bit) | ||||||||||

| SoC | Broadcom BCM2835[32] | Broadcom BCM2837B0[26] | Broadcom BCM2835[32] | Broadcom BCM2836 | Broadcom BCM2837 | Broadcom BCM2837B0[26] | Broadcom BCM2711[85] | Broadcom BCM2835[92] | Broadcom BCM2837 | Broadcom BCM2837B0 | Broadcom BCM2835 | |||||||

| FPU | VFPv2; NEON not supported | VFPv4 + NEON | VFPv2; NEON not supported | VFPv3 + NEON | VFPv4 + NEON | VFPv2; NEON not supported | VFPv4 + NEON | VFPv2; NEON not supported | ||||||||||

| CPU | 1× ARM1176JZF-S 700 MHz | 4× Cortex-A53 1.4 GHz | 1× ARM1176JZF-S 700 MHz | 4× Cortex-A7 900 MHz | 4× Cortex-A53 900 MHz | 4× Cortex-A53 1.2 GHz | 4× Cortex-A53 1.4 GHz | 4× Cortex-A72 1.5 GHz[31] | 1× ARM1176JZF-S 700 MHz | 4× Cortex-A53 1.2 GHz | 1× ARM1176JZF-S 1 GHz | |||||||

| GPU | Broadcom VideoCore IV @ 250 MHz[lower-alpha 2] | Broadcom VideoCore VI @ 500 MHz[93] | Broadcom VideoCore IV @ 250 MHz[lower-alpha 2] | |||||||||||||||

| Memory (SDRAM)[94] | 256 MiB | 256 or 512 MiB Changed to 512 MiB on 10th August 2016[95] |

512 MiB | 256 or 512 MiB Changed to 512 MiB on 15th October 2012[96] |

512 MiB | 1 GiB | 1 GiB | 1, 2, 4 or 8 GiB | 512 MiB | 1 GiB | 512 MiB | |||||||

| USB 2.0 ports[65] | 1[lower-alpha 4] | 1[lower-alpha 5] | 2[lower-alpha 6][97] | 4[lower-alpha 7][61][83][98] | 2[85] | 1[lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 1] | 1[lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 1] | 1[lower-alpha 5][lower-alpha 1] | 1 Micro-USB[lower-alpha 4] | |||||||||

| USB 3.0 ports | 0 | 2[85] | 0 | |||||||||||||||

| Video input | 15-pin MIPI camera interface (CSI) connector, used with the Raspberry Pi camera or Raspberry Pi NoIR camera[99] | 2× MIPI camera interface (CSI)[lower-alpha 1][92][100][101] | None | MIPI camera interface (CSI)[102] | ||||||||||||||

| HDMI | 1× HDMI (rev 1.3) | 2× HDMI (rev 2.0) via Micro-HDMI[31] | 1× HDMI[lower-alpha 1] | 1× Mini-HDMI | ||||||||||||||

| Composite video | via RCA jack | via 3.5 mm CTIA style TRRS jack | via RCA jack | via 3.5 mm CTIA style TRRS jack | Yes[lower-alpha 1][100][103] | via marked points on PCB for optional header pins[104] | ||||||||||||

| MIPI display interface (DSI)[lower-alpha 8] | Yes | Yes[lower-alpha 1][92][101][105][106] | No | |||||||||||||||

| Audio inputs | As of revision 2 boards via I²S[107] | |||||||||||||||||

| Audio outputs | Analog via 3.5 mm phone jack; digital via HDMI and, as of revision 2 boards, I²S | Analog, HDMI, I²S[lower-alpha 1] | Mini-HDMI, stereo audio through PWM on GPIO | |||||||||||||||

| On-board storage[65] | SD, MMC, SDIO card slot (3.3 V with card power only) | MicroSDHC slot[83] | SD, MMC, SDIO card slot | MicroSDHC slot | MicroSDHC slot, USB Boot Mode[108] | 4 GiB eMMC flash memory chip[92] | MicroSDHC slot | 8/16/32 GiB eMMC flash memory chip[92] | MicroSDHC slot | |||||||||

| Ethernet (8P8C)[65] | None[109] | None | 10/100 Mbit/s USB adapter on the USB hub[97] |

10/100 Mbit/s | 10/100/1000 Mbit/s[98] (real speed max 300 Mbit/s)[110] | 10/100/1000 Mbit/s[85] | None | None | ||||||||||

| WiFi IEEE 802.11 wireless | b/g/n/ac dual band 2.4/5 GHz | None | b/g/n single band 2.4 GHz | b/g/n/ac dual band 2.4/5 GHz | b/g/n single band 2.4 GHz | |||||||||||||

| Bluetooth | 4.2 BLE | None | 4.1 BLE | 4.2 LS BLE | 5.0[85] | 4.1 BLE | ||||||||||||

| Low-level peripherals | 8× GPIO[111] plus the following, which can also be used as GPIO: UART, I²C bus, SPI bus with two chip selects, I²S audio[112] +3.3 V, +5 V, ground[113][114] |

17× GPIO plus the same specific functions, and HAT ID bus | 8× GPIO plus the following, which can also be used as GPIO: UART, I²C bus, SPI bus with two chip selects, I²S audio +3.3 V, +5 V, ground. | 17× GPIO plus the same specific functions, and HAT ID bus | 17× GPIO plus the same specific functions, HAT, and an additional 4× UART, 4× SPI, and 4× I2C connectors.[115] | 46× GPIO, some of which can be used for specific functions including I²C, SPI, UART, PCM, PWM[lower-alpha 1][116] | 17× GPIO plus the same specific functions, and HAT ID bus[8] | |||||||||||

| Power ratings | 300 mA (1.5 W)[117] | 200 mA (1 W)[118] | 700 mA (3.5 W) | 200 mA (1 W) average when idle, 350 mA (1.75 W) maximum under stress (monitor, keyboard and mouse connected)[119] | 220 mA (1.1 W) average when idle, 820 mA (4.1 W) maximum under stress (monitor, keyboard and mouse connected)[119] | 300 mA (1.5 W) average when idle, 1.34 A (6.7 W) maximum under stress (monitor, keyboard, mouse and WiFi connected)[119] | 459 mA (2.295 W) average when idle, 1.13 A (5.661 W) maximum under stress (monitor, keyboard, mouse and WiFi connected)[120] | 600 mA (3 W) average when idle, 1.25 A (6.25 W) maximum under stress (monitor, keyboard, mouse and Ethernet connected),[119] 3 A (15 W) power supply recommended[2] | 200 mA (1 W) | 700 mA (3.5 W) | 100 mA (0.5 W) average when idle, 350 mA (1.75 W) maximum under stress (monitor, keyboard and mouse connected)[119] | |||||||

| Power source | 5 V via MicroUSB or GPIO header | 5 V via USB-C or GPIO header | 5 V[lower-alpha 1] | 5 V via MicroUSB or GPIO header | ||||||||||||||

| Size | 85.6 mm × 56.5 mm (3.37 in × 2.22 in)[lower-alpha 9] |

65 mm × 56.5 mm × 10 mm (2.56 in × 2.22 in × 0.39 in)[lower-alpha 10] |

65 mm × 56.5 mm (2.56 in × 2.22 in) |

85.60 mm × 56.5 mm (3.370 in × 2.224 in)[lower-alpha 9] |

85.60 mm × 56.5 mm × 17 mm (3.370 in × 2.224 in × 0.669 in)[121] |

67.6 mm × 30 mm (2.66 in × 1.18 in) |

67.6 mm × 31 mm (2.66 in × 1.22 in) |

65 mm × 30 mm × 5 mm (2.56 in × 1.18 in × 0.20 in) | ||||||||||

| Weight | 31 g (1.1 oz) |

23 g (0.81 oz) |

45 g (1.6 oz) |

46 g (1.6 oz)[122] |

7 g (0.25 oz)[123] |

9 g (0.32 oz)[124] | ||||||||||||

| Console | Adding a USB network interface via tethering[109] or a serial cable with optional GPIO power connector[125] | |||||||||||||||||

| Generation | 1 | 1+ | 3+ | 1 | 1+ | 2 | 2 ver 1.2 | 3 | 3+ | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 Lite | 3+ | 3+ Lite | PCB ver 1.2 | PCB ver 1.3 | W (wireless) |

| Obsolescence Statement |

N/A | in production until at least January 2022 | in production until at least January 2023 | N/A | in production until at least January 2022 | N/A | in production until at least January 2022 | in production until at least January 2026[126] | in production until at least January 2023 | in production until at least January 2026 | N/A | N/A | N/A | in production until at least January 2026 | N/A, or see PCB ver 1.3 | in production until at least January 2022 | in production until at least January 2026 | |

| Type | Model A | Model B | Compute Module[lower-alpha 1] | Zero | ||||||||||||||

- All interfaces are via 200-pin DDR2 SO-DIMM connector.

- BCM2837: 3D part of GPU at 300 MHz, video part of GPU at 400 MHz,[113][127] OpenGL ES 2.0 (BCM2835, BCM2836: 24 GFLOPS / BCM2837: 28.8 GFLOPS). MPEG-2 and VC-1 (with licence),[128] 1080p30 H.264/MPEG-4 AVC high-profile decoder and encoder[32] (BCM2837: 1080p60)

- Direct from the BCM2835 chip.

- Direct from the BCM2837B0 chip.

- via on-board 3-port USB hub; one USB port internally connected to the Ethernet port.

- via on-board 5-port USB hub; one USB port internally connected to the Ethernet port.

- for raw LCD panels

- Excluding protruding connectors.

- Same as HAT board.

Software

Operating systems

The Raspberry Pi Foundation provides Raspberry Pi OS (formerly called Raspbian), a Debian-based (32-bit) Linux distribution for download, as well as third-party Ubuntu, Windows 10 IoT Core, RISC OS, and specialised media centre distributions.[129] It promotes Python and Scratch as the main programming languages, with support for many other languages.[130] The default firmware is closed source, while unofficial open source is available.[131][132][133] Many other operating systems can also run on the Raspberry Pi. Third-party operating systems available via the official website include Ubuntu MATE, Windows 10 IoT Core, RISC OS and specialised distributions for the Kodi media centre and classroom management.[134] The formally verified microkernel seL4 is also supported.[135]

- Other operating systems (not Linux-based)

- Broadcom VCOS – Proprietary operating system which includes an abstraction layer designed to integrate with existing kernels, such as ThreadX (which is used on the VideoCore4 processor), providing drivers and middleware for application development. In case of Raspberry Pi this includes an application to start the ARM processor(s) and provide the publicly documented API over a mailbox interface, serving as its firmware. An incomplete source of a Linux port of VCOS is available as part of the reference graphics driver published by Broadcom.[136]

- RISC OS Pi (a special cut down version RISC OS Pico, for 16 MiB cards and larger for all models of Pi 1 & 2, has also been made available.)

- FreeBSD[137][138]

- NetBSD[139][140]

- OpenBSD (only on 64-bit platforms, such as Raspberry Pi 3)[141]

- Plan 9 from Bell Labs[142][143] and Inferno[144] (in beta)

- Windows 10 IoT Core – a zero-price edition of Windows 10 offered by Microsoft that runs natively on the Raspberry Pi 2.[145]

- Haiku – an open source BeOS clone that has been compiled for the Raspberry Pi and several other ARM boards.[146] Work on Pi 1 began in 2011, but only the Pi 2 will be supported.[147]

- HelenOS – a portable microkernel-based multiserver operating system; has basic Raspberry Pi support since version 0.6.0[148]

- Other operating systems (Linux-based)

- Android Things – an embedded version of the Android operating system designed for IoT device development.

- Arch Linux ARM – a port of Arch Linux for ARM processors.

- openSUSE[149]

- SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 12 SP2[150]

- SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 12 SP3 (Commercial support)[150]

- Gentoo Linux[151]

- Lubuntu[152]

- Xubuntu[152]

- Devuan

- CentOS for Raspberry Pi 2 and later

- RedSleeve (a RHEL port) for Raspberry Pi 1

- Slackware ARM – version 13.37 and later runs on the Raspberry Pi without modification.[153][154][155][156] The 128–496 MiB of available memory on the Raspberry Pi is at least twice the minimum requirement of 64 MiB needed to run Slackware Linux on an ARM or i386 system.[157] (Whereas the majority of Linux systems boot into a graphical user interface, Slackware's default user environment is the textual shell / command line interface.[158]) The Fluxbox window manager running under the X Window System requires an additional 48 MiB of RAM.[159]

- Kali Linux – a Debian-derived distro designed for digital forensics and penetration testing.

- SolydXK – a light Debian-derived distro with Xfce.

- Ark OS – designed for website and email self-hosting.

- Sailfish OS with Raspberry Pi 2 (due to use ARM Cortex-A7 CPU; Raspberry Pi 1 uses different ARMv6 architecture and Sailfish requires ARMv7.)[160]

- Tiny Core Linux – a minimal Linux operating system focused on providing a base system using BusyBox and FLTK. Designed to run primarily in RAM.

- Alpine Linux – a Linux distribution based on musl and BusyBox, primarily designed for "power users who appreciate security, simplicity and resource efficiency".

- postmarketOS - distribution based on Alpine Linux, primarily developed for smartphones.

- Void Linux – a rolling release Linux distribution which was designed and implemented from scratch, provides images based on musl or glibc.

- Fedora – supports Pi 2 and later since Fedora 25 (Pi 1 is supported by some unofficial derivatives, e.g. listed here.).

- OpenWrt – a highly extensible Linux distribution for embedded devices (typically wireless routers). It supports Pi 1, 2, 3, 4 and Zero W.[161]

Driver APIs

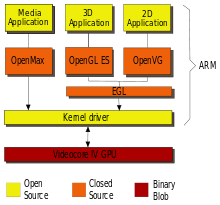

Raspberry Pi can use a VideoCore IV GPU via a binary blob, which is loaded into the GPU at boot time from the SD-card, and additional software, that initially was closed source.[162] This part of the driver code was later released.[163] However, much of the actual driver work is done using the closed source GPU code. Application software makes calls to closed source run-time libraries (OpenMax, OpenGL ES or OpenVG), which in turn call an open source driver inside the Linux kernel, which then calls the closed source VideoCore IV GPU driver code. The API of the kernel driver is specific for these closed libraries. Video applications use OpenMAX, 3D applications use OpenGL ES and 2D applications use OpenVG, which both in turn use EGL. OpenMAX and EGL use the open source kernel driver in turn.[164]

Vulkan driver

The Raspberry Pi Foundation first announced it was working on a Vulkan driver in February of 2020.[165] A working Vulkan driver running Quake 3 at 100 frames per second on a 3B+ was revealed by a graphics engineer that had been working on it as a hobby project on June 20th.[166]

Firmware

The official firmware is a freely redistributable[167] binary blob, that is proprietary software.[146] A minimal proof-of-concept open source firmware is also available, mainly aimed at initialising and starting the ARM cores as well as performing minimal startup that is required on the ARM side. It is also capable of booting a very minimal Linux kernel, with patches to remove the dependency on the mailbox interface being responsive. It is known to work on Raspberry Pi 1, 2 and 3, as well as some variants of Raspberry Pi Zero.[168]

Third-party application software

- AstroPrint – AstroPrint's wireless 3D printing software can be run on the Pi 2.[169]

- C/C++ Interpreter Ch – Released 3 January 2017, C/C++ interpreter Ch and Embedded Ch are released free for non-commercial use for Raspberry Pi, ChIDE is also included for the beginners to learn C/C++.[170]

- Mathematica & the Wolfram Language – These were released free as a standard part of the Raspbian NOOBS image in November 2013.[171][172][173] As of 12 February 2020, the version is Mathematica 12.0.[174] Programs can be run either from a command line interface or from a Notebook interface. There are Wolfram Language functions for accessing connected devices.[175] There is also a Wolfram Language desktop development kit allowing development for Raspberry Pi in Mathematica from desktop machines, including features from the loaded Mathematica version such as image processing and machine learning.[176][177][178]

- Minecraft – Released 11 February 2013, a modified version that allows players to directly alter the world with computer code.[179]

- RealVNC – Since 28 September 2016, Raspbian includes RealVNC's remote access server and viewer software.[180][181][182] This includes a new capture technology which allows directly-rendered content (e.g. Minecraft, camera preview and omxplayer) as well as non-X11 applications to be viewed and controlled remotely.[183][184]

- UserGate Web Filter – On 20 September 2013, Florida-based security vendor Entensys announced porting UserGate Web Filter to Raspberry Pi platform.[185]

- Steam Link – On 13 December 2018, Valve released official Steam Link game streaming client for the Raspberry Pi 3 and 3 B+.[186][187]

Software development tools

- Arduino IDE – for programming an Arduino.

- Algoid – for teaching programming to children and beginners.

- BlueJ – for teaching Java to beginners.

- Greenfoot – Greenfoot teaches object orientation with Java. Create 'actors' which live in 'worlds' to build games, simulations, and other graphical programs.

- Julia – an interactive and cross-platform programming language/environment, that runs on the Pi 1 and later.[188] IDEs for Julia, such as Juno, are available. See also Pi-specific Github repository JuliaBerry.

- Lazarus[189] – a Free Pascal RAD IDE

- LiveCode – an educational RAD IDE descended from HyperCard using English-like language to write event-handlers for WYSIWYG widgets runnable on desktop, mobile and Raspberry Pi platforms.

- Ninja-IDE – a cross-platform integrated development environment (IDE) for Python.

- Processing – an IDE built for the electronic arts, new media art, and visual design communities with the purpose of teaching the fundamentals of computer programming in a visual context.

- Scratch – a cross-platform teaching IDE using visual blocks that stack like Lego, originally developed by MIT's Life Long Kindergarten group. The Pi version is very heavily optimised[190] for the limited computer resources available and is implemented in the Squeak Smalltalk system. The latest version compatible with The 2 B is 1.6.

- Squeak Smalltalk – a full-scale open Smalltalk.

- TensorFlow – an artificial intelligence framework developed by Google. The Raspberry Pi Foundation worked with Google to simplify the installation process through pre-built binaries.[191]

- Thonny – a Python IDE for beginners.

- V-Play Game Engine – a cross-platform development framework that supports mobile game and app development with the V-Play Game Engine, V-Play apps, and V-Play plugins.

- Xojo – a cross-platform RAD tool that can create desktop, web and console apps for Pi 2 and Pi 3.

- C-STEM Studio – a platform for hands-on integrated learning of computing, science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (C-STEM) with robotics.

- Erlang - a functional language for building concurrent systems with light-weight processes and message passing.

- LabVIEW Community Edition - a system-design platform and development environment for a visual programming language from National Instruments.

Accessories

- Gertboard – A Raspberry Pi Foundation sanctioned device, designed for educational purposes, that expands the Raspberry Pi's GPIO pins to allow interface with and control of LEDs, switches, analogue signals, sensors and other devices. It also includes an optional Arduino compatible controller to interface with the Pi.[192]

- Camera – On 14 May 2013, the foundation and the distributors RS Components & Premier Farnell/Element 14 launched the Raspberry Pi camera board alongside a firmware update to accommodate it.[193] The camera board is shipped with a flexible flat cable that plugs into the CSI connector which is located between the Ethernet and HDMI ports. In Raspbian, the user must enable the use of the camera board by running Raspi-config and selecting the camera option. The camera module costs €20 in Europe (9 September 2013).[194] It can produce 1080p, 720p and 640x480p video. The dimensions are 25 mm × 20 mm × 9 mm.[194] In May 2016, v2 of the camera came out, and is an 8 megapixel camera.

- Infrared Camera – In October 2013, the foundation announced that they would begin producing a camera module without an infrared filter, called the Pi NoIR.[195]

- Official Display – On 8 September 2015, The foundation and the distributors RS Components & Premier Farnell/Element 14 launched the Raspberry Pi Touch Display[196]

- HAT (Hardware Attached on Top) expansion boards – Together with the Model B+, inspired by the Arduino shield boards, the interface for HAT boards was devised by the Raspberry Pi Foundation. Each HAT board carries a small EEPROM (typically a CAT24C32WI-GT3)[197] containing the relevant details of the board,[198] so that the Raspberry Pi's OS is informed of the HAT, and the technical details of it, relevant to the OS using the HAT.[199] Mechanical details of a HAT board, which uses the four mounting holes in their rectangular formation, are available online.[200][201]

- High Quality Camera - In May 2020, the 12.3 megapixel Sony IMXZ477 sensor camera module was released with support for C- and CS-mount lenses.[202] The unit initially retailed for $50 USD with interchangeable lenses starting at $25 USD.

Vulnerability to flashes of light

In February 2015, a switched-mode power supply chip, designated U16, of the Raspberry Pi 2 Model B version 1.1 (the initially released version) was found to be vulnerable to flashes of light,[203] particularly the light from xenon camera flashes and green[204] and red laser pointers. However, other bright lights, particularly ones that are on continuously, were found to have no effect. The symptom was the Raspberry Pi 2 spontaneously rebooting or turning off when these lights were flashed at the chip. Initially, some users and commenters suspected that the electromagnetic pulse (EMP) from the xenon flash tube was causing the problem by interfering with the computer's digital circuitry, but this was ruled out by tests where the light was either blocked by a card or aimed at the other side of the Raspberry Pi 2, both of which did not cause a problem. The problem was narrowed down to the U16 chip by covering first the system on a chip (main processor) and then U16 with Blu-Tack (an opaque poster mounting compound). Light being the sole culprit, instead of EMP, was further confirmed by the laser pointer tests,[204] where it was also found that less opaque covering was needed to shield against the laser pointers than to shield against the xenon flashes.[203] The U16 chip seems to be bare silicon without a plastic cover (i.e. a chip-scale package or wafer-level package), which would, if present, block the light. Unofficial workarounds include covering U16 with opaque material (such as electrical tape,[203][204] lacquer, poster mounting compound, or even balled-up bread[203]), putting the Raspberry Pi 2 in a case,[204] and avoiding taking photos of the top side of the board with a xenon flash. This issue was not discovered before the release of the Raspberry Pi 2 because it is not standard or common practice to test susceptibility to optical interference,[203] while commercial electronic devices are routinely subjected to tests of susceptibility to radio interference.

Reception and use

Technology writer Glyn Moody described the project in May 2011 as a "potential BBC Micro 2.0", not by replacing PC compatible machines but by supplementing them.[205] In March 2012 Stephen Pritchard echoed the BBC Micro successor sentiment in ITPRO.[206] Alex Hope, co-author of the Next Gen report, is hopeful that the computer will engage children with the excitement of programming.[207] Co-author Ian Livingstone suggested that the BBC could be involved in building support for the device, possibly branding it as the BBC Nano.[208] The Centre for Computing History strongly supports the Raspberry Pi project, feeling that it could "usher in a new era".[209] Before release, the board was showcased by ARM's CEO Warren East at an event in Cambridge outlining Google's ideas to improve UK science and technology education.[210]

Harry Fairhead, however, suggests that more emphasis should be put on improving the educational software available on existing hardware, using tools such as Google App Inventor to return programming to schools, rather than adding new hardware choices.[211] Simon Rockman, writing in a ZDNet blog, was of the opinion that teens will have "better things to do", despite what happened in the 1980s.[212]

In October 2012, the Raspberry Pi won T3's Innovation of the Year award,[213] and futurist Mark Pesce cited a (borrowed) Raspberry Pi as the inspiration for his ambient device project MooresCloud.[214] In October 2012, the British Computer Society reacted to the announcement of enhanced specifications by stating, "it's definitely something we'll want to sink our teeth into."[215]

In June 2017, Raspberry Pi won the Royal Academy of Engineering MacRobert Award.[216] The citation for the award to the Raspberry Pi said it was "for its inexpensive credit card-sized microcomputers, which are redefining how people engage with computing, inspiring students to learn coding and computer science and providing innovative control solutions for industry."[217]

Clusters of hundreds of Raspberry Pis have been used for testing programs destined for supercomputers[218]

Community

The Raspberry Pi community was described by Jamie Ayre of FLOSS software company AdaCore as one of the most exciting parts of the project.[219] Community blogger Russell Davis said that the community strength allows the Foundation to concentrate on documentation and teaching.[219] The community developed a fanzine around the platform called The MagPi[220] which in 2015, was handed over to the Raspberry Pi Foundation by its volunteers to be continued in-house.[221] A series of community Raspberry Jam events have been held across the UK and around the world.[222]

Education

As of January 2012, enquiries about the board in the United Kingdom have been received from schools in both the state and private sectors, with around five times as much interest from the latter. It is hoped that businesses will sponsor purchases for less advantaged schools.[223] The CEO of Premier Farnell said that the government of a country in the Middle East has expressed interest in providing a board to every schoolgirl, to enhance her employment prospects.[224][225]

In 2014, the Raspberry Pi Foundation hired a number of its community members including ex-teachers and software developers to launch a set of free learning resources for its website.[226] The Foundation also started a teacher training course called Picademy with the aim of helping teachers prepare for teaching the new computing curriculum using the Raspberry Pi in the classroom.[227]

In 2018, NASA launched the JPL Open Source Rover Project, which is a scaled down of Curiosity rover and uses a Raspberry Pi as the control module, to encourage students and hobbyists to get involved in mechanical, software, electronics, and robotics engineering.[228]

Home automation

There are a number of developers and applications that are using the Raspberry Pi for home automation. These programmers are making an effort to modify the Raspberry Pi into a cost-affordable solution in energy monitoring and power consumption. Because of the relatively low cost of the Raspberry Pi, this has become a popular and economical alternative to the more expensive commercial solutions.[229]

Industrial automation

In June 2014, Polish industrial automation manufacturer TECHBASE released ModBerry, an industrial computer based on the Raspberry Pi Compute Module. The device has a number of interfaces, most notably RS-485/232 serial ports, digital and analogue inputs/outputs, CAN and economical 1-Wire buses, all of which are widely used in the automation industry. The design allows the use of the Compute Module in harsh industrial environments, leading to the conclusion that the Raspberry Pi is no longer limited to home and science projects, but can be widely used as an Industrial IoT solution and achieve goals of Industry 4.0.[230]

In March 2018, SUSE announced commercial support for SUSE Linux Enterprise on the Raspberry Pi 3 Model B to support a number of undisclosed customers implementing industrial monitoring with the Raspberry Pi.[231]

Commercial products

OTTO is a digital camera created by Next Thing Co. It incorporates a Raspberry Pi Compute Module. It was successfully crowd-funded in a May 2014 Kickstarter campaign.[232]

Slice is a digital media player which also uses a Compute Module as its heart. It was crowd-funded in an August 2014 Kickstarter campaign. The software running on Slice is based on Kodi.[233]

COVID-19 pandemic

In Q1 of 2020, during the coronavirus pandemic, Raspberry Pi computers saw a large increase in demand primarily due to the increase in working from home, but also because of the use of many Raspberry Pi Zeros in ventilators for COVID-19 patients in countries such as Colombia,[234] which were used to combat strain on the healthcare system. In March 2020, Raspberry Pi sales reached 640,000 units, the second largest month of sales in the company's history.[235]

Astro Pi

A project was launched in December 2014 at an event held by the UK Space Agency. The Astro Pis are augmented Raspberry Pis and included Sensor Hats and either a visible-light Raspberry Pi camera or an infrared raspberry Pi camera. The Astro Pi competition, called Principia, was officially opened in January and was opened to all primary and secondary school aged children who were residents of the United Kingdom. During his mission, British ESA astronaut Tim Peake deployed the computers on board the International Space Station.[236] He loaded the winning code while in orbit, collected the data generated and then sent this to Earth where it was distributed to the winning teams. Covered themes during the competition included spacecraft sensors, satellite imaging, space measurements, data fusion and space radiation.

The organisations involved in the Astro Pi competition include the UK Space Agency, UKspace, Raspberry Pi, ESERO-UK and ESA.

In 2017, the European Space Agency ran another competition open to all students in the European Union called Proxima. The winning programs were ran on the ISS by Thomas Pesquet, a French astronaut.[237]

History

In 2006, early concepts of the Raspberry Pi were based on the Atmel ATmega644 microcontroller. Its schematics and PCB layout are publicly available.[238] Foundation trustee Eben Upton assembled a group of teachers, academics and computer enthusiasts to devise a computer to inspire children.[223] The computer is inspired by Acorn's BBC Micro of 1981.[239][240] The Model A, Model B and Model B+ names are references to the original models of the British educational BBC Micro computer, developed by Acorn Computers.[241] The first ARM prototype version of the computer was mounted in a package the same size as a USB memory stick.[242] It had a USB port on one end and an HDMI port on the other.

The Foundation's goal was to offer two versions, priced at US$25 and $35. They started accepting orders for the higher priced Model B on 29 February 2012,[243] the lower cost Model A on 4 February 2013.[244] and the even lower cost (US$20) A+ on 10 November 2014.[82] On 26 November 2015, the cheapest Raspberry Pi yet, the Raspberry Pi Zero, was launched at US$5 or £4.[245] According to Upton, the name "Raspberry Pi" was chosen with "Raspberry" as an ode to a tradition of naming early computer companies after fruit, and "Pi" as a reference to the Python programming language.[246]

Pre-launch

- July 2011: Trustee Eben Upton publicly approached the RISC OS Open community in July 2011 to enquire about assistance with a port.[247] Adrian Lees at Broadcom has since worked on the port,[248][249] with his work being cited in a discussion regarding the graphics drivers.[250] This port is now included in NOOBS.

- August 2011 – 50 alpha boards are manufactured. These boards were functionally identical to the planned Model B,[251] but they were physically larger to accommodate debug headers. Demonstrations of the board showed it running the LXDE desktop on Debian, Quake 3 at 1080p,[252] and Full HD MPEG-4 video over HDMI.[253]

- October 2011 – A version of RISC OS 5 was demonstrated in public, and following a year of development the port was released for general consumption in November 2012.[254][255][256][257]

- December 2011 – Twenty-five Model B Beta boards were assembled and tested[258] from one hundred unpopulated PCBs.[259] The component layout of the Beta boards was the same as on production boards. A single error was discovered in the board design where some pins on the CPU were not held high; it was fixed for the first production run.[260] The Beta boards were demonstrated booting Linux, playing a 1080p movie trailer and the Rightware Samurai OpenGL ES benchmark.[261]

- Early 2012 – During the first week of the year, the first 10 boards were put up for auction on eBay.[262][263] One was bought anonymously and donated to the museum at The Centre for Computing History in Cambridge, England.[209][264] The ten boards (with a total retail price of £220) together raised over £16,000,[265] with the last to be auctioned, serial number No. 01, raising £3,500.[266] In advance of the anticipated launch at the end of February 2012, the Foundation's servers struggled to cope with the load placed by watchers repeatedly refreshing their browsers.[267]

Launch

- 19 February 2012 – The first proof of concept SD card image that could be loaded onto an SD card to produce a preliminary operating system is released. The image was based on Debian 6.0 (Squeeze), with the LXDE desktop and the Midori browser, plus various programming tools. The image also runs on QEMU allowing the Raspberry Pi to be emulated on various other platforms.[268][269]

- 29 February 2012 – Initial sales commence 29 February 2012[270] at 06:00 UTC;. At the same time, it was announced that the model A, originally to have had 128 MiB of RAM, was to be upgraded to 256 MiB before release.[243] The Foundation's website also announced: "Six years after the project's inception, we're nearly at the end of our first run of development – although it's just the beginning of the Raspberry Pi story."[271] The web-shops of the two licensed manufacturers selling Raspberry Pi's within the United Kingdom, Premier Farnell and RS Components, had their websites stalled by heavy web traffic immediately after the launch (RS Components briefly going down completely).[272][273] Unconfirmed reports suggested that there were over two million expressions of interest or pre-orders.[274] The official Raspberry Pi Twitter account reported that Premier Farnell sold out within a few minutes of the initial launch, while RS Components took over 100,000 pre orders on day one.[243] Manufacturers were reported in March 2012 to be taking a "healthy number" of pre-orders.[219]

- March 2012 – Shipping delays for the first batch were announced in March 2012, as the result of installation of an incorrect Ethernet port,[275][276] but the Foundation expected that manufacturing quantities of future batches could be increased with little difficulty if required.[277] "We have ensured we can get them [the Ethernet connectors with magnetics] in large numbers and Premier Farnell and RS Components [the two distributors] have been fantastic at helping to source components," Upton said. The first batch of 10,000 boards was manufactured in Taiwan and China.[278][279]

- 8 March 2012 – Release Raspberry Pi Fedora Remix, the recommended Linux distribution,[280] developed at Seneca College in Canada.[281]

- March 2012 – The Debian port is initiated by Mike Thompson, former CTO of Atomz. The effort was largely carried out by Thompson and Peter Green, a volunteer Debian developer, with some support from the Foundation, who tested the resulting binaries that the two produced during the early stages (neither Thompson nor Green had physical access to the hardware, as boards were not widely accessible at the time due to demand).[282] While the preliminary proof of concept image distributed by the Foundation before launch was also Debian-based, it differed from Thompson and Green's Raspbian effort in a couple of ways. The POC image was based on then-stable Debian Squeeze, while Raspbian aimed to track then-upcoming Debian Wheezy packages.[269] Aside from the updated packages that would come with the new release, Wheezy was also set to introduce the armhf architecture,[283] which became the raison d'être for the Raspbian effort. The Squeeze-based POC image was limited to the armel architecture, which was, at the time of Squeeze's release, the latest attempt by the Debian project to have Debian run on the newest ARM embedded-application binary interface (EABI).[284] The armhf architecture in Wheezy intended to make Debian run on the ARM VFP hardware floating-point unit, while armel was limited to emulating floating point operations in software.[285][286] Since the Raspberry Pi included a VFP, being able to make use of the hardware unit would result in performance gains and reduced power use for floating point operations.[282] The armhf effort in mainline Debian, however, was orthogonal to the work surrounding the Pi and only intended to allow Debian to run on ARMv7 at a minimum, which would mean the Pi, an ARMv6 device, would not benefit.[283] As a result, Thompson and Green set out to build the 19,000 Debian packages for the device using a custom build cluster.[282]

Post-launch

- 16 April 2012 – Reports appear from the first buyers who had received their Raspberry Pi.[287][288]

- 20 April 2012 – The schematics for the Model A and Model B are released.[289]

- 18 May 2012 – The Foundation reported on its blog about a prototype camera module they had tested.[290] The prototype used a 14-megapixel module.

- 22 May 2012 – Over 20,000 units had been shipped.[291]

- July 2012 – Release of Raspbian.[292]

- 16 July 2012 – It was announced that 4,000 units were being manufactured per day, allowing Raspberry Pis to be bought in bulk.[293][294]

- 24 August 2012 – Hardware accelerated video (H.264) encoding becomes available after it became known that the existing licence also covered encoding. Formerly it was thought that encoding would be added with the release of the announced camera module.[295][296] However, no stable software exists for hardware H.264 encoding.[297] At the same time the Foundation released two additional codecs that can be bought separately, MPEG-2 and Microsoft's VC-1. Also it was announced that the Pi will implement CEC, enabling it to be controlled with the television's remote control.[128]

- 5 September 2012 – The Foundation announced a second revision of the Raspberry Pi Model B.[298] A revision 2.0 board is announced, with a number of minor corrections and improvements.[299]

- 6 September 2012 – Announcement that in future the bulk of Raspberry Pi units would be manufactured in the UK, at Sony's manufacturing facility in Pencoed, Wales. The Foundation estimated that the plant would produce 30,000 units per month, and would create about 30 new jobs.[300][301]

- 15 October 2012 – It is announced that new Raspberry Pi Model Bs are to be fitted with 512 MiB instead of 256 MiB RAM.[302]

- 24 October 2012 – The Foundation announces that "all of the VideoCore driver code which runs on the ARM" had been released as free software under a BSD-style licence, making it "the first ARM-based multimedia SoC with fully-functional, vendor-provided (as opposed to partial, reverse engineered) fully open-source drivers", although this claim has not been universally accepted.[163] On 28 February 2014, they also announced the release of full documentation for the VideoCore IV graphics core, and a complete source release of the graphics stack under a 3-clause BSD licence[303][304]

- October 2012 – It was reported that some customers of one of the two main distributors had been waiting more than six months for their orders. This was reported to be due to difficulties in sourcing the CPU and conservative sales forecasting by this distributor.[305]

- 17 December 2012 – The Foundation, in collaboration with IndieCity and Velocix, opens the Pi Store, as a "one-stop shop for all your Raspberry Pi (software) needs". Using an application included in Raspbian, users can browse through several categories and download what they want. Software can also be uploaded for moderation and release.[306]

- 3 June 2013 – "New Out of Box Software" or NOOBS is introduced. This makes the Raspberry Pi easier to use by simplifying the installation of an operating system. Instead of using specific software to prepare an SD card, a file is unzipped and the contents copied over to a FAT formatted (4 GiB or bigger) SD card. That card can then be booted on the Raspberry Pi and a choice of six operating systems is presented for installation on the card. The system also contains a recovery partition that allows for the quick restoration of the installed OS, tools to modify the config.txt and an online help button and web browser which directs to the Raspberry Pi Forums.[307]

- October 2013 – The Foundation announces that the one millionth Pi had been manufactured in the United Kingdom.[308]

- November 2013: they announce that the two millionth Pi shipped between 24 and 31 October.[309]

- 28 February 2014 – On the day of the second anniversary of the Raspberry Pi, Broadcom, together with the Raspberry Pi foundation, announced the release of full documentation for the VideoCore IV graphics core, and a complete source release of the graphics stack under a 3-clause BSD licence.[303][304]

- 7 April 2014 – The official Raspberry Pi blog announced the Raspberry Pi Compute Module, a device in a 200-pin DDR2 SO-DIMM-configured memory module (though not in any way compatible with such RAM), intended for consumer electronics designers to use as the core of their own products.[92]

- June 2014 – The official Raspberry Pi blog mentioned that the three millionth Pi shipped in early May 2014.[310]

- 14 July 2014 – The official Raspberry Pi blog announced the Raspberry Pi Model B+, "the final evolution of the original Raspberry Pi. For the same price as the original Raspberry Pi model B, but incorporating numerous small improvements people have been asking for".[83]

- 10 November 2014 – The official Raspberry Pi blog announced the Raspberry Pi Model A+.[82] It is the smallest and cheapest (US$20) Raspberry Pi so far and has the same processor and RAM as the Model A. Like the A, it has no Ethernet port, and only one USB port, but does have the other innovations of the B+, like lower power, micro-SD-card slot, and 40-pin HAT compatible GPIO.

- 2 February 2015 – The official Raspberry Pi blog announced the Raspberry Pi 2. Looking like a Model B+, it has a 900 MHz quad-core ARMv7 Cortex-A7 CPU, twice the memory (for a total of 1 GiB) and complete compatibility with the original generation of Raspberry Pis.[311]

- 14 May 2015 – The price of Model B+ was decreased from US$35 to $25, purportedly as a "side effect of the production optimizations" from the Pi 2 development.[312] Industry observers have sceptically noted, however, that the price drop appeared to be a direct response to the CHIP, a lower-priced competitor discontinued in April 2017.[313]

- 26 November 2015 – The Raspberry Pi Foundation launched the Raspberry Pi Zero, the smallest and cheapest member of the Raspberry Pi family yet, at 65 mm × 30 mm, and US$5. The Zero is similar to the Model A+ without camera and LCD connectors, while smaller and uses less power. It was given away with the Raspberry Pi magazine Magpi No. 40 that was distributed in the UK and US that day – the MagPi was sold out at almost every retailer internationally due to the freebie.[8]

- 29 February 2016 – Raspberry Pi 3 with a BCM2837 1.2 GHz 64-bit quad processor based on the ARMv8 Cortex-A53, with built-in Wi-Fi BCM43438 802.11n 2.4 GHz and Bluetooth 4.1 Low Energy (BLE). Starting with a 32-bit Raspbian version, with a 64-bit version later to come if "there is value in moving to 64-bit mode". In the same announcement it was said that a new BCM2837 based Compute Module was expected to be introduced a few months later.[314]

- February 2016 – The Raspberry Pi Foundation announces that they had sold eight million devices (for all models combined), making it the best-selling UK personal computer, ahead of the Amstrad PCW.[315][316] Sales reached ten million in September 2016.[16]

- 25 April 2016 – Raspberry Pi Camera v2.1 announced with 8 Mpixels, in normal and NoIR (can receive IR) versions. The camera uses the Sony IMX219 chip with a resolution of 3280 × 2464. To make use of the new resolution the software has to be updated.[317]

- 10 October 2016 – NEC Display Solutions announces that select models of commercial displays to be released in early 2017 will incorporate a Raspberry Pi 3 Compute Module.[318]

- 14 October 2016 – Raspberry Pi Foundation announces their co-operation with NEC Display Solutions. They expect that the Raspberry Pi 3 Compute Module will be available to the general public by the end of 2016.[319]

- 25 November 2016 – 11 million units sold.[320]

- 16 January 2017 – Compute Module 3 and Compute Module 3 Lite are launched.[88]

- 28 February 2017 – Raspberry Pi Zero W with WiFi and Bluetooth via chip scale antennas launched.[321][322]

- 14 March 2018 – On Pi Day, Raspberry Pi Foundation introduced Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+ with improvements in the Raspberry PI 3B computers performance, updated version of the Broadcom application processor, better wireless Wi-Fi and Bluetooth performance and addition of the 5 GHz band.[323]

- 15 November 2018 – Raspberry Pi 3 Model A+ launched.[324]

- 28 January 2019 – Compute Module 3+ (CM3+/Lite, CM3+/8 GiB, CM3+/16 GiB and CM3+/32 GiB) launched.[89]

- 24 June 2019 – Raspberry Pi 4 Model B launched.[325]

- 10 December 2019 – 30 million units sold;[326] sales are about 6 million per year.[327][328]

- 28 May 2020 – 8GB Raspberry Pi 4 announced for $75. The operating system is no longer called "Raspbian", but "Raspberry Pi OS", and an official 64-bit version is now available in beta.[329]

Sales

According to the Raspberry Pi Foundation, more than 5 million Raspberry Pis were sold by February 2015, making it the best-selling British computer.[18] By November 2016 they had sold 11 million units,[320][330] and 12.5 million by March 2017, making it the third best-selling "general purpose computer".[331] In July 2017, sales reached nearly 15 million,[332] climbing to 19 million in March 2018.[26] By December 2019, a total of 30 million devices had been sold.[19]

See also

References

- Halfacree, Gareth (March 2020). "Raspberry Pi 4 now comes with 2GB RAM Minimum". The MagPi (91). Raspberry Pi Press. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "Raspberry Pi 4 on sale now from $35". 24 June 2019.

- Upton, Eben (28 May 2020). "8GB Raspberry Pi 4 on sale now at $75". Raspberry Pi Blog. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "Windows 10 for IoT". Raspberry Pi Foundation. 30 April 2015.

- Hattersley, Lucy. "Raspberry Pi 4, 3A+, Zero W - specs, benchmarks & thermal tests". The MagPi magazine. Raspberry Pi Trading Ltd. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "DATASHEET – Raspberry Pi Compute Module 3+" (PDF). www.raspberrypi.org. 1 January 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "Raspberry Pi 4 Tech Specs". Raspberry Pi. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "Raspberry Pi Zero: the $5 Computer". Raspberry Pi Foundation. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- "BCM2835 - Raspberry Pi Documentation". raspberrypi.org.

- "BCM2711 - Raspberry Pi Documentation". raspberrypi.org.

- "BCM2835 - Raspberry Pi Documentation". raspberrypi.org.

- https://www.raspberrypi.org/documentation/hardware/raspberrypi/bcm2711/rpi_DATA_2711_1p0_preliminary.pdf

- Cellan-Jones, Rory (5 May 2011). "A£15 computer to inspire young programmers". BBC News.

- Price, Peter (3 June 2011). "Can a £15 computer solve the programming gap?". BBC Click. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- Bush, Steve (25 May 2011). "Dongle computer lets kids discover programming on a TV". Electronics Weekly. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- "Ten millionth Raspberry Pi, and a new kit – Raspberry Pi". 8 September 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

we've beaten our wildest dreams by three orders of magnitude

- "The Raspberry Pi in scientific research". Raspberry Pi. 25 April 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Gibbs, Samuel (18 February 2015). "Raspberry Pi becomes best selling British computer". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- Upton, Ebon (14 December 2019). "Ebon Upton tweet - sales up to 30 million". the twitter. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- "About Us". sonypencoed.co.uk. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Tung, Liam (27 July 2017). "Raspberry Pi: 14 million sold, 10 million made in the UK | ZDNet". ZDNet.

- "New $10 Raspberry Pi Zero comes with Wi-Fi and Bluetooth". Ars Technica. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- "The $10 Raspberry Pi Zero W brings Wi-Fi and Bluetooth to the minuscule micro". PC World. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- "Zero WH: Pre-soldered headers and what to do with them". Raspberry Pi Foundation. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- "Eben Upton talks Raspberry Pi 3". The MagPi Magazine. 29 February 2016.

- Upton, Eben (14 March 2018). "Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+ on Sale at $35". Raspberry Pi Blog. Raspberry Pi Foundation. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- "Confirmed: Raspberry Pi 4 suffers from significant USB-C design flaw". Android Authority. 10 July 2019.

- "The Raspberry Pi 4 doesn't work with all USB-C cables".

- "Tested: 10+ Raspberry Pi 4 USB-C Cables That Work". Tom's Hardware. 13 July 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

you’ll still need an AC adapter that delivers 5 volts and at least 3 amps of power so, unless you already have one, your best bet might be to buy the official Raspberry Pi 4 power supply, which comes with a built-in cable and goes for $8 to $10.

- Richard Speed (21 February 2020). "Get in the C: Raspberry Pi 4 can handle a wider range of USB adapters thanks to revised design's silent arrival". The Register.

- 23 June, Nick Heath in Hardware on; 2019; Pst, 11:00 Pm. "Raspberry Pi 4 Model B review: This board really can replace your PC". TechRepublic. Retrieved 24 June 2019.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "BCM2835 Media Processor; Broadcom". Broadcom.com. 1 September 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- Brose, Moses (30 January 2012). "Broadcom BCM2835 SoC has the most powerful mobile GPU in the world?". Grand MAX. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- Shimpi, Anand Lal. "The iPhone 3GS Hardware Exposed & Analyzed". Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- "Raspberry Pi 2 on sale now at $35". Raspberry Pi Foundation. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- "Raspberry Pi 2, Model B V1.2 Technical Specifications" (PDF). RS Components. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- "Buy a Raspberry Pi 3 Model B – Raspberry Pi". raspberrypi.org.

- "Raspberry Pi 3 Model A+"./

- "Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+"./

- "Raspberry Pi 4 Model B specifications". Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Merten, Dr. Maik (14 September 2019). "Raspi-Kernschau - Das Prozessor-Innenleben des Raspberry Pi 4 im Detail" [Raspi-kernel-show - The inner life of the Raspberry Pi 4 processor in detail]. c't (in German). 2019 (20): 164–169.

- "22. Raspberry Pi 4 — Trusted Firmware-A documentation". trustedfirmware-a.readthedocs.io. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- "Playing with a Raspberry Pi 4 64-bit | CloudKernels". blog.cloudkernels.net. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- "Raspberry Pi Zero". Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "Performance – measures of the Raspberry Pi's performance". RPi Performance. eLinux.org. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Benchoff, Brian. "64 Rasberry Pis turned into a supercomputer". Hackaday. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- "Raspberry Pi2 – Power and Performance Measurement". RasPi.TV. RasPi.TV. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- Upton, Eben (29 February 2016). "Raspberry Pi 3 on sale now at $35 – Raspberry Pi". Raspberry Pi. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- "How Much Power Does Raspberry Pi3B Use? How Fast Is It Compared To Pi2B?". RasPi.TV. RasPi.TV. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- "Introducing turbo mode: up to 50% more performance for free". Raspberrypi.org. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- "asb/raspi-config on Github". asb. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- Overclocking options – raspberrypi.org

- "I have a Raspberry Pi Beta Board AMA". reddit.com. 15 January 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "Raspberry Pi boot configuration text file". raspberrypi.org. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012.

- "Nokia 701 has a similar Broadcom GPU". raspberrypi.org. 2 February 2012. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- "introducing new firmware for the 512 MiB Pi". Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- "Raspberry Pi 3 A+ specs". raspberrypi.org. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- "Raspberry Pi 3 specs". raspberrypi.org. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Raspberry Pi 2 specs". raspberrypi.org. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Raspberry Pi 4 specs". raspberrypi.org. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- "Microchip/SMSC LAN9514 data sheet;" (PDF). Microchip. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "seemoo-lab/nexmon". GitHub.

- "Turning your Raspberry PI Zero into a USB Gadget". Adafruit Learning System.

- "USB mass storage device boot - Raspberry Pi Documentation". raspberrypi.org.

- "Verified USB Peripherals and SDHC Cards;". Elinux.org. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "GPIO – Raspberry Pi Documentation". raspberrypi.org. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- "Raspberry Pi, supported video resolutions". eLinux.org. 30 November 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- "Pi Screen limited to 1920 by RISC OS:-". RISC OS Open. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

2048 × 1152 monitor is the highest resolution the Pi's GPU can handle [presumably with non-low frame-rate ..] The monitors screen info confirms the GPU is outputting 2048×1152

- "RISC OS Open: Forum: Latest Pi firmware?". riscosopen.org.

- "Raspberry Pi and 4k @ 15Hz". Retrieved 6 January 2016.

I have managed to get 3840 x 2160 (4k x 2k) at 15Hz on a Seiki E50UY04 working

- "Raspberry Pi 3 announced with OSMC support". 28 February 2016.

- "Raspberry Pi 3 Model B" (PDF).

- Ozolins, Jason. "examples of Raspberry Pi composite output". Raspberrypi.org. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- James Adams (28 July 2014). "Raspberry Pi B+ (Reduced Schematics) 1.2" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2014.

- James Adams (4 April 2016). "Raspberry Pi 3 Model B (Reduced Schematics) 1.2" (PDF).

- "Raspberry Pi Rev 1.0 Model AB schematics" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2014.

- "Raspberry Pi Rev 2.0 Model AB schematics" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2014.

- "Raspberry Pi Rev 2.1 Model AB schematics" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2014.

- "Raspberry Pi Rev 1.0 Model AB schematics" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2014.

- Eben Upton (5 September 2012). "Upcoming board revision". Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- "Model A now for sale in Europe – buy one today!". Raspberry Pi Foundation. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- "Introducing Raspberry Pi Model A+". Raspberry Pi Foundation. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- "Introducing Raspberry Pi Model B+". Raspberry Pi Foundation. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- http://www.farnell.com/datasheets/2163186.pdf?_ga=1.9528053.1789915275.1482632652

- Amadeo, Ron (24 June 2019). "The Raspberry Pi 4 brings faster CPU, up to 4 GiB of RAM". Ars Technica. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- "Raspberry Pi gets more Arduino-y with new open source modular hardware". Ars Technica. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- Brodkin, Jon (16 January 2017). "Raspberry Pi upgrades Compute Module with 10 times the CPU performance". Ars Technica. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- Compute Module 3 Launch, Raspberry Pi Foundation

- Adams, James. "Compute Module 3+ on sale now from $25". raspberrypi.org. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- Bowater, Donna (29 February 2012). "Mini Raspberry Pi computer goes on sale for £22". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- Eben Upton (14 May 2015). "Price Cut! Raspberry Pi Model B+ Now Only $25".

- "Raspberry Pi Compute Module: New Product!". Raspberry Pi Foundation. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- "Raspberry Pi 4 specs and benchmarks". The MagPi Magazine. 24 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- "Raspberry Pi revision codes". Raspberry Pi Documentation. 28 May 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "Raspberry Pi Modal A+ 512MB RAM". Adafruit. 10 August 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "Model B Now Ships with 512MB of RAM". Raspberry Pi Blog. 15 October 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "SMSC LAN9512 Website;". Smsc.com. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "ProductCompare LAN7515 LAN9514". Microchip. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "diagram of Raspberry Pi with CSI camera connector". Elinux.org. 2 March 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- Adams, James (3 April 2014). "Raspberry Pi Compute Module electrical schematic diagram" (PDF). Raspberry Pi Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Adams, James (3 April 2014). "Raspberry Pi Compute Module IO Board electrical schematic diagram" (PDF). Raspberry Pi Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Upton, Eben (16 May 2016). "zero grows camera connector". Raspberry Pi Foundation. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- Adams, James (7 April 2014). "Comment by James Adams on Compute Module announcement". Raspberry Pi Foundation. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- "Pi Zero – The New Raspberry Pi Board • Pi Supply". Pi Supply.

- "Raspberry Pi Wiki, section screens". Elinux.org. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "diagram of Raspberry Pi with DSI LCD connector". Elinux.org. Retrieved 6 May 2012.