Queen Anne's Revenge

Queen Anne's Revenge was an early-18th-century ship, most famously used as a flagship by Edward Teach (or Edward Thatch), better known by his nickname Blackbeard. Although the date and place of the ship's construction are uncertain,[3] it was originally believed she was built for merchant service in Bristol, England in 1710 and named Concord,[4] later captured by French privateers and renamed La Concorde. This origin hypothesis was found to be incorrect and has been dismissed by the project crew.[5] After several years' service with the French (both as a naval frigate and as a merchant vessel – much of the time as a slave trading ship), she was captured by Blackbeard in 1717. Blackbeard used the ship for less than a year,[6] but captured numerous prizes using her as his flagship.

Illustration published in 1736 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | La Concorde |

| Launched: | c. 1710 |

| History | |

| Name: | Queen Anne's Revenge |

| Fate: | Ran aground on 10 June 1718 near Beaufort Inlet, North Carolina |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Ship |

| Tons burthen: | 200 bm |

| Length: | 103 ft (31.4 m) |

| Beam: | 24.6 ft (7.5 m) |

| Sail plan: | Full-rigged |

| Complement: | up to 300 in Blackbeard's service |

| Armament: | 40 cannons (alleged), 30 found[1] |

Queen Anne's Revenge | |

| |

| Nearest city | Atlantic Beach, North Carolina |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | c. 1710 |

| NRHP reference No. | 04000148[2] |

| Added to NRHP | March 9, 2004 |

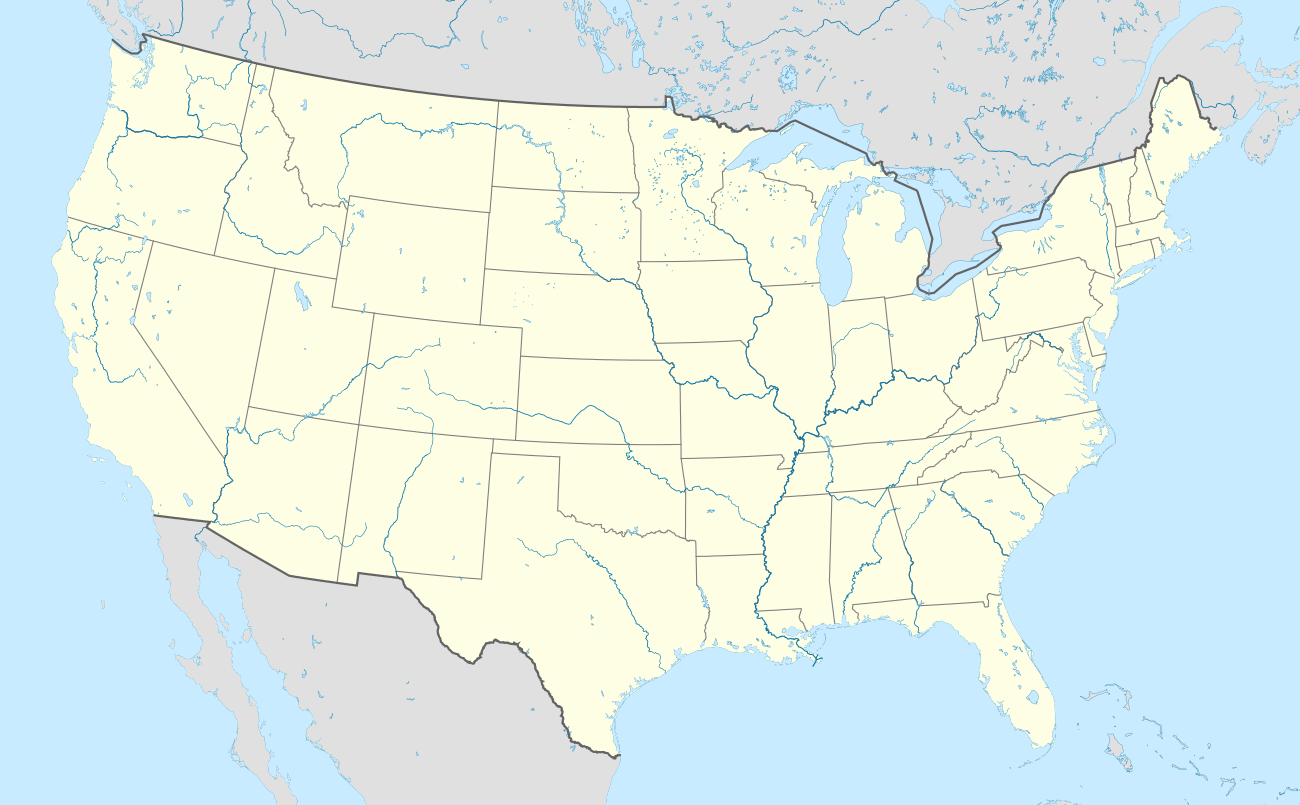

In May 1718, Blackbeard ran the ship aground at Topsail Inlet, now known as Beaufort Inlet, North Carolina, United States, in the present-day Carteret County.[6] After the grounding, her crew and supplies were transferred to smaller ships. In 1996 Intersal, Inc., a private firm, discovered the remains of a vessel that was later determined to be Queen Anne's Revenge,[7] which was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

History

The ship that would be known as Queen Anne's Revenge was a 200-ton vessel believed to have been built in 1710. She was handed over to René Duguay-Trouin and employed in his service for some time before being converted into a slave ship, then operated by the leading slave trader René Montaudin of Nantes, until sold in 1713 in Peru or Chile. She was briefly re-acquired by the French Navy in November 1716, but was sold by them for commerce five months later in France, again for use as a slaver.[8] She was captured by Blackbeard and his pirates on 28 November 1717, near the island of Saint Vincent in the West Indies.[9]

After selling her cargo of slaves at Martinique, Blackbeard made the vessel into his flagship, adding more heavy cannon and renaming her Queen Anne's Revenge. The name may come from the War of the Spanish Succession, known in the Americas as Queen Anne's War, in which Blackbeard had served in the Royal Navy, or possibly from sympathy for the Jacobite cause (Queen Anne being the last Stuart monarch).[10] Blackbeard sailed this ship from the west coast of Africa to the Caribbean, attacking British, Dutch, and Portuguese merchant ships along the way.

Shortly after blockading Charleston harbor in May 1718, and refusing to accept the Governor's offer of a pardon, Blackbeard ran Queen Anne's Revenge aground while entering Beaufort Inlet, North Carolina on 10 June 1718. A deposition given by David Herriot, the former captain of the sloop Adventure, states "Thatch's [Teach's] ship Queen Anne's Revenge run a-ground off of the Bar of Topsail-Inlet." He also states that Adventure "run a-ground likewise about Gun-shot from the said Thatch" in an attempt to kedge Queen Anne's Revenge off the bar.[11] Blackbeard then disbanded his flotilla and escaped by transferring supplies onto the smaller Adventure. He stranded several crew members on a small island nearby, where they were later rescued by Captain Stede Bonnet. Some[12] suggest Blackbeard deliberately grounded the ship as an excuse to disperse the crew. Shortly afterward, he surrendered and accepted a royal pardon for himself and his remaining crewmen from Governor Charles Eden at Bath, North Carolina. However, Blackbeard eventually returned to piracy and was killed in combat in November 1718.[11]

Discovery and excavation

Intersal Inc., a private research firm, discovered the wreck believed to be Queen Anne’s Revenge on November 21, 1996.[13] It was located by Intersal's director of operations, Mike Daniel, who used historical research provided by the company's president, Phil Masters[14][15][16] and maritime archaeologist David Moore.[17] The shipwreck lies in 28 feet (8.5 m) of water about one mile (1.6 km) offshore of Fort Macon State Park (34°41′44″N 76°41′20″W), Atlantic Beach, North Carolina. Thirty-one cannons have been identified to date and more than 300,000 artifacts have been recovered.[18] The cannons are of different origins including Sweden, England and possibly France, and of different sizes as would be expected with a colonial pirate crew.[11]

Recognizing the significance of Queen Anne's Revenge, the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources (NCDNCR), Intersal, and Maritime Research Institute (MRI) entered into a memorandum of agreement in 1998.[19] Intersal agreed to forego entitlement to any coins and precious metals recovered from the wreck site in order that all artifacts remain as one intact collection, and in order for NCDNCR to determine the ultimate disposition of the artifacts. In return, Intersal was granted media-, replica- and other rights related to an entity known as Blackbeard's Queen Anne's Revenge Shipwreck Project;[20] MRI was granted joint artifact touring rights with NCDNCR. NCDNCR, Intersal, and Rick Allen of Nautilus Productions signed a settlement agreement[21] on October 24, 2013 connected to commercial-, replica- and promotional opportunities for the benefit of Queen Anne's Revenge. The State of North Carolina owns the wreck since it lies in state waters (within the three-mile limit).

For one week in 2000 and 2001, live underwater video of the project was webcast to the Internet as a part of the QAR DiveLive[22] educational program that reached thousands of children around the world.[23] Created and co-produced by Nautilus Productions and Marine Grafics, this project enabled students to talk to scientists and learn about methods and technologies utilized by the underwater archaeology team.[24][25]

In November 2006 and 2007, more artifacts were discovered at the site and brought to the surface. The additional artifacts appear to support the claim that the wreck is that of Queen Anne's Revenge. Among evidence to support this theory is that the cannons were found loaded. In addition, there were more cannons than would be expected for a ship of this size, and the cannons were of different makes. Depth markings on the part of the stern that was recovered point to it having been made according to the French foot measurements.[26]

By the end of 2007, approximately one third of the wreck was fully excavated. Part of the hull of the ship, including much of the keel and part of the stern post, has survived. The 1,500-pound (680 kg) stern post was recovered in November 2007.[27][28] The NCDNCR set up the website[29] Queen Anne's Revenge to build on intense public interest in the finds. Artifacts recovered in 2008 include loose ceramic and pewter fragments, lead strainer fragments, a nesting weight, cannon apron, ballast stones, a sword guard and a coin.[30]

Goals during the 2010 field season included staging of one of the ship's largest main deck cannons to the large artifact holding area on site, taking corrosion readings from anchors and cannon undergoing in situ corrosion treatment, attaching aluminum-alloy anodes to the remaining anchors and cannons so as to begin their in situ corrosion treatment and continuing site excavations.[31]

In 2011, the 1.4-tonne (3,100 lb) anchor from the ship was brought to the surface along with a range of makeshift weaponry including langrage or canister shot.[32][33]

On August 29, 2011, the National Geographic Society reported that the State of North Carolina had confirmed the shipwreck as Queen Anne's Revenge, reversing a conclusion previously maintained because of a lack of conclusive evidence.[34] Specific artifacts that support this conclusion include a brass coin weight bearing the bust of Queen Anne of England, cast during her reign (1702–1714); the stem of a wine glass decorated with diamonds and tiny embossed crowns, made to commemorate the 1714 coronation of Queen Anne's successor, King George I; the remains of a French hunting sword featuring a bust that closely resembles King Louis XV, who claimed the French throne in 1715; and a urethral syringe for treating venereal diseases with a control mark indicating manufacture between 1707 and 1715 in Paris, France.[35]

On June 21, 2013, the National Geographic Society reported recovery of two cannons from Queen Anne's Revenge.[36] Several months later, on October 28, archaeologists recovered five more cannons from the wreck.[37] Three of these have been identified as iron 6-pounders manufactured at Ehrendals works in Södermanland, Sweden, in 1713. Thomas Roth, the head of Sweden's Armament Museum Research Department, derived the origin of the iron cannons by a mark on their tubes.[38]

The 23rd of 31 cannons identified at the wreck site was recovered on October 24, 2014. The gun is approximately 56 inches (140 cm) long, weighs over 300 pounds (140 kg) and may be a sister to a Swedish gun that was previously recovered. Nine cannonballs, bar shot halves, an iron bolt and a grenado were also recovered during the 2014 field season.[39]

Archaeological recovery ceased on the shipwreck after the 2015 season because of lawsuits filed against the State of North Carolina, the NCDNCR, and the Friends of the Queen Anne's Revenge nonprofit.[40] Intersal, which discovered the Queen Anne's Revenge, filed suit in state court over contract violations.[41][42] In a unanimous decision on November 2, 2019, the North Carolina Supreme Court affirmed Intersal's complaint and voted to send the lawsuit back to complex business court for reconsideration.[43] Nautilus Productions, the company documenting the recovery since 1998, filed suit in federal court over copyright violations and the passage of "Blackbeard's Law" by the North Carolina legislature.[44][45][46] On November 5, 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Allen v. Cooper. A decision in the case is expected in the late spring of 2020.[47][48][49][50]

In January 2018, sixteen fragments of paper were identified after being recovered from sludge inside a cannon. The scraps were from a copy of the book A Voyage to the South Sea, and Round the World, Perform'd in the Years 1708, 1709, 1710 and 1711 by Captain Edward Cooke, in which Cooke travels under Woodes Rogers; it is likely the pages were torn from the book and used as wadding in that cannon.[51]

National Register of Historic Places

Queen Anne's Revenge was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2004. The reference number is 04000148. It is listed as owned by the State of North Carolina and located near Morehead City.[52] The wreck site is designated 31CR314 by the state of North Carolina.[53]

In popular culture

- "Queen Anne's Revenge" is the title of a song by American Celtic punk band Flogging Molly, from their third album Within a Mile of Home.

- "Queen Anne's Revenge" is a jazz song recorded by The Sean J. Kennedy Quartet featuring drummer Liberty DeVitto.[54]

- Queen Anne's Revenge appears in the 2011 film Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, portrayed by Sunset, a ship which previously portrayed the Black Pearl in the film's predecessors: Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest and Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End.[55] This incarnation of the ship was shown to shoot Greek fire from its prow. Queen Anne's Revenge also appeared in the Pirates of the Caribbean Online video game.[56] The ship returned in the 2017 film Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales where it served as the flagship of Hector Barbossa's pirate fleet.

- It appears in the video game Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag by Ubisoft. The ship is briefly playable during a mission to assist Blackbeard.

- It also appears in Rick Riordan's novel The Sea of Monsters, in which Percy Jackson and Annabeth Chase escape Circe's island.

- The ship appears in the DC's Legends of Tomorrow episode "The Curse of the Earth Totem".

- The ship also appears in the 2004 remake of the video game Sid Meier's Pirates! at first as an NPC ship captained by Blackbeard, but which can be captured and used as a player ship if the player defeats Blackbeard in battle.

References

- "Pirate Arms and Armament | Queen Anne's Revenge Project". www.qaronline.org. Archived from the original on 2017-12-02.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "The Pirate Ship's Journey - Queen Anne's Revenge Project". www.qaronline.org. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "Queen Anne's Revenge - Story of Blackbeard's Ship". www.thewayofthepirates.com. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Kircher, Kenneth W. (2017). Queen Anne's Revenge: A Systems Analysis of Blackbeard's Flagship. MA thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri, Columbia.

- Brian Handwerk (2005-07-12). "'Blackbeard's Ship' Yields New Clues to Pirate Mystery". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2011-10-15. Retrieved 2011-05-27.

- "Intersal Discovers Blackbeard's Flagship!". Intersal, Inc. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Rif Winfield (2017), French Warships in the Age of Sail 1626-1786: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates, p.234. Seaforth Publishing, Barnsley. ISBN 978-1-4738-9351-1.

- "The Pirate Ship's Journey | Queen Anne's Revenge Project". www.qaronline.org. Archived from the original on 2017-10-23. Retrieved 2017-12-01.

- "Blackbeard (Edward Thatch) Biography -- The Republic of Pirates". www.republicofpirates.net. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- D. Moore. (1997) "A General History of Blackbeard the Pirate, the Queen Anne's Revenge and the Adventure". In Tributaries, Volume VII, 1997. pp. 31–35. (North Carolina Maritime History Council)

- Cordingly, David (1996). Life Among The Pirates. London, England: Abacus. ISBN 978-0349113142.

- "QAR Discovered". lat3440.com. Intersal, Inc. Archived from the original on 17 July 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- "In Shipwreck Linked to Pirate, State Sees a Tourism Treasure". The New York Times.

- White, Fred A. "East Carolina Dive and Historical Recovery Team, Beaufort Inlet and Oregon Inlet Surveys, 1982 Field Reports". East Carolina Dive and Historical Recovery Team. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- "Globe-trotting archaeologist finds treasure right under his feet". East Carolina University. August 19, 2013. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved June 21, 2014.

- Gray, Nancy (February 1998). "Maps and microfilm: tools of a Blackbeard sleuth". The ECU Report. Archived from the original on November 23, 2011. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 9, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Queen Anne's Revenge Fact Sheet" (PDF). qaronline.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-04.

- "Blackbeard's Queen Anne's Revenge Shipwreck Project". Nautilus Productions.

- "Mediated Settlement Agreement". Scribd.com. Archived from the original on 2015-04-13.

- "Live from Morehead City, it's Queen Anne's Revenge :: State Publications". digital.ncdcr.gov. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- C Southerly and J Gillman-Bryan. (2003). "Diving on the Queen Anne's Revenge". In: SF Norton (ed). Diving for Science...2003. Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences (22nd Annual Scientific Diving Symposium). Archived from the original on 2008-07-05. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- "Apple, QuickTime help with underwater diving trip". Macworld. Archived from the original on 2015-04-03.

- "Blackbeard's Glowing Shipwreck". P3 Update. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-04-10.

- "Secrets of the Dead: Blackbeard's Lost Ship". PBS. Archived from the original on 2010-06-20.

- Malcom, Corey. "The Iron Bilboes of the Henrietta Marie" (PDF). melfisher.org. The Navigator: Newsletter of the Mel Fisher Maritime Heritage Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2015. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- Donovan, Chelsea. "Queen Anne's Revenge Artifact Found - WITN". YouTube. Archived from the original on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- qaronline.org Archived 2016-03-12 at the Wayback Machine: The Queen Anne's Revenge Shipwreck Project - Archaeological Investigations of Blackbeard's Flagship.

- Welsh, Wendy. "2008 Queen Anne's Revenge Shipwreck Field Summary" (PDF). qaronline.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- Southerly, Chris. "Queen Anne's Revenge Shipwreck Project - 2010 Field Expedition" (PDF). qaronline.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- "Blackbeard's Queen Anne's Revenge wreck reveals secrets of the real Pirate of the Caribbean". The Daily Telegraph, UK. May 29, 2011. Archived from the original on May 28, 2011. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- "'Blackbeard anchor' lifted in US". 28 May 2011. Archived from the original on 28 December 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2018 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- Drye, Willie (August 29, 2011). "Blackbeard's Ship Confirmed off North Carolina". Daily News. National Geographic. Archived from the original on September 25, 2011. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- Zucchino, David (9 June 2011). "Effort to tie North Carolina shipwreck to pirate Blackbeard advances". LA Times. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- "Archaeologists Recover Two More Cannons From Blackbeard's Ship". National Geographic. June 21, 2013. Archived from the original on June 27, 2013. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- "Archaeologists recover 5 cannons from wreck of Blackbeard's ship". Fox News. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- "Kapten Svartskägg sköt svenskt". NyTeknik. November 4, 2013. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- "Pirate Blackbeard's Newly Recovered Cannon to be Shared with Public". Popular Archaeology. October 31, 2014. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- Drye, Willie. "Blackbeard's Ship Confirmed off North Carolina". National Geographic. National Geographic. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- "Intersal, Inc. v Hamilton, et al". North Carolina Judicial Branch. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- Hand, Bill (15 May 2019). "Lawsuit over Blackbeard's pirate ship goes before NC Supreme Court". Fayetteville Observer. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- Waggoner, Martha (4 November 2019). "Treasure hunter vows legal showdown over Blackbeard shipwreck". Associated Press. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- "Allen v Cooper, et al". Supreme Court of the United States. Supreme Court of the United States. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- Gresko, Jessica (3 June 2019). "High court will hear copyright dispute involving pirate ship". Associated Press. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- Wolverton, Paul (2 November 2019). "Pirate ship lawsuit from Fayetteville goes to Supreme Court on Tuesday". Fayetteville Observer. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Murphy, Brian (5 November 2019). "How Blackbeard's ship and a diver with an 'iron hand' ended up at the Supreme Court". Charlotte Observer. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Wolf, Richard (5 November 2019). "Aarrr, matey! Supreme Court justices frown on state's public display of pirate ship's salvage operation". USA Today. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Livni, Ephrat (5 November 2019). "A Supreme Court piracy case involving Blackbeard proves truth is stranger than fiction". Quartz. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Woolverton, Paul (5 November 2019). "Supreme Court justices skeptical in Blackbeard pirate ship case from Fayetteville". Fayetteville Observer. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "Rare Scraps of Paper Unearthed in the Sludge of Famed Pirate Ship". Smithsonian Magazine. January 9, 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- "National Register of Historical Places - NORTH CAROLINA (NC), Carteret County". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2007-02-07. Archived from the original on 2016-11-16.

- "The Shipwreck". qaronline.org. Archived from the original on 2015-09-07.

- "Queen Anne's Revenge". Allaboutjazz.com. Archived from the original on 2012-11-11.

- "Pirates of the Caribbean". Cinemareview.com. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27.

- "The Queen Anne's Revenge Sets Sail!". Piratesonline.go.com. Archived from the original on 2013-10-07.

External links

- N.C Supreme Court revives lawsuit over Blackbeard’s ship and lost Spanish treasure ship, Fayetteville Observer

- Queen Anne's Revenge: Archaeological Site, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources

- Blackbeard's Ship Confirmed off North Carolina National Geographic News

- Piracy worries in pirate pursuit Blackbeard, Baltimore Sun

- Philip Masters, True Amateur of History, Dies at 70, New York Times

- Episode 955: Pirate Videos, Planet Money, NPR

- National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service

- Scientists Show Relics From Ship Fit For Pirate, Possibly Blackbeard, Chicago Tribune

- Resurrecting the Notorious Queen Anne's Revenge, ARTpublika Magazine