Province of North Carolina

The Province of North Carolina was a British colony that existed in North America from 1712 to 1776, created as a proprietary colony. The power of the British government was vested in a governor of North Carolina, but the colony declared independence from Great Britain in 1776. The Province of North Carolina had four capitals: Bath (1712–1722), Edenton (1722–1743), Brunswick (1743–1770), and New Bern (after 1770). The colony later became the states of North Carolina and Tennessee, and parts of the colony combined with other territory to form the states of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi.[1]

Province of North Carolina | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1712–1776 | |||||||||

Motto: Quae Sera Tamen Respexit "Which, though late, looked upon me" | |||||||||

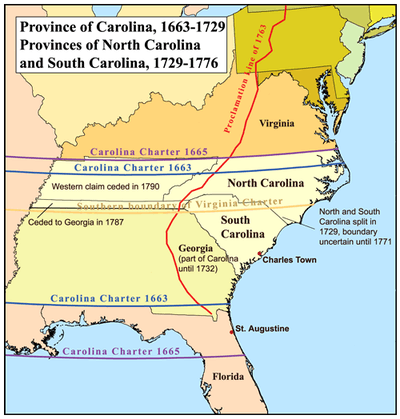

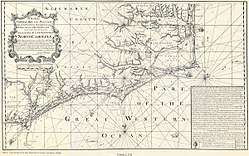

Map of the Province of North Carolina, the Province of South Carolina and the former Province of Carolina | |||||||||

| Status | Colony of Great Britain | ||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||

| Official languages | English | ||||||||

| Government |

| ||||||||

| Legislature | General Assembly | ||||||||

| Provincial Council and Governor | |||||||||

| Colonial Assembly or House of Burgesses | |||||||||

| Historical era | Georgian era | ||||||||

• Separation from Province of Carolina | January 24, 1712 | ||||||||

| July 4, 1776 | |||||||||

| Currency | North Carolina pound | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | United States

| ||||||||

History

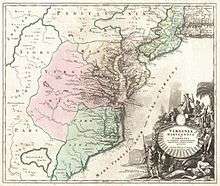

King Charles II of England granted the Carolina charter in 1663 for land south of Virginia Colony and north of Spanish Florida. He granted the land to eight Lords Proprietors in return for their financial and political assistance in restoring him to the throne in 1660.[2] The northern half of the colony differed significantly from the southern half, and transportation and communication were difficult between the two regions, so a separate deputy governor was named to administer the northern half of the colony starting in 1691.[3]

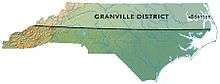

The division of the colony into north and south was completed at a meeting of the Lords Proprietors held at Craven House[lower-alpha 1] in London on December 7, 1710, although the same proprietors continued to control both colonies. The first Governor of the separate North Carolina province was Edward Hyde. Unrest against the proprietors in South Carolina in 1719 led King George I to appoint a royal governor in that colony, whereas the Lords Proprietor continued to appoint the governor of North Carolina.[5] Both Carolinas became royal colonies in 1729, after the British government had tried for nearly 10 years to locate and buy out seven of the eight Lords Proprietors. The remaining one-eighth share of the Province was retained by members of the Carteret family until 1776, part of North Carolina known as the Granville District.[6]

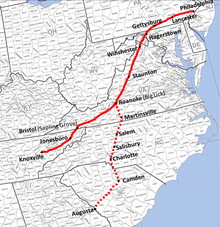

In the late eighteenth century, the tide of immigration to North Carolina from Virginia and Pennsylvania began to swell.[7] The Scots-Irish (Ulster Protestants) from what is today Northern Ireland were the largest immigrant group from the British Isles to the colonies before the Revolution.[8][9][10][9] In total, English indentured servants, who arrived mostly in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, comprised the majority of English settlers prior to the Revolution.[10][11] On the eve of the American Revolution, North Carolina was the fastest-growing British colony in North America. The small family farms of Piedmont contrasted sharply with the plantation economy of the coastal region, where wealthy planters had established a slave society, growing tobacco and rice with slave labor.

Differences in the settlement patterns of eastern and western North Carolina, or the low country and uplands, affected the political, economic, and social life of the state from the eighteenth until the twentieth century. The Tidewater in eastern North Carolina was settled chiefly by immigrants from rural England and the Scottish Highlands. The upcountry of western North Carolina was settled chiefly by Scots-Irish, English and German Protestants, the so-called "cohee". During the Revolutionary War, the English and Highland Scots of eastern North Carolina tended to remain loyal to the British Crown, because of longstanding business and personal connections with Great Britain. The English, Welsh, Scots-Irish and German settlers of western North Carolina tended to favor American independence from Britain.

With no cities and very few towns or villages, the colony was rural and thinly populated. Local taverns provided multiple services ranging from strong drink, beds for travelers, and meeting rooms for politicians and businessmen. In a world sharply divided along lines of ethnicity, gender, race, and class, the tavern keepers' rum proved a solvent that mixed together all sorts of locals, as well as travelers. The increasing variety of drinks on offer and the emergence of private clubs meeting in the taverns showed that genteel culture was spreading from London to the periphery of the English world.[12]

The courthouse was usually the most imposing building in a county. Jails were often an important part of the courthouse but were sometimes built separately. Some county governments built tobacco warehouses to provide a common service for their most important export crop.[13]

Expansion westward began early in the 18th century from the province's seats of power on the coast, particularly after the conclusion of the Tuscarora and Yamasee wars, in which the largest barrier was removed to colonial settlement farther inland. Settlement in large numbers became more feasible over the Appalachian Mountains after the French and Indian War and the accompanying Anglo-Cherokee War, in which the Cherokee and Catawba tribes were effectively neutralized. King George III issued the Proclamation of 1763 in order to stifle potential conflict with Indians in that region, including the Cherokee. This barred any settlement near the headwaters of any rivers or streams that flowed westward towards the Mississippi River. It included several North Carolina rivers, such as the French Broad River and Watauga River. This proclamation was not strictly obeyed and was widely detested in North Carolina, but it somewhat delayed migration westward until after the American Revolutionary War.[5]

Settlers continued to flow westwards in smaller numbers, despite the prohibition, and several trans-Appalachian settlements were formed. Most prominent was the Watauga Association, formed in 1772 as an independent territory within the bounds of North Carolina which adopted its own written constitution. Notable frontiersmen such as Daniel Boone traveled back and forth across the invisible proclamation line as market hunters, seeking valuable pelts to sell in eastern settlements, and many served as leaders and guides for groups who settled in the Tennessee River valley and the Kentucke country.

Geography and administrative divisions

The oldest precincts (counties) were Albemarle County (1664–1689) and Bath County (1696–1739). During the period of 1668 to 1774, 32 counties were created. As western counties, such as Anson and Rowan Counties were created, their western borders were not well defined and extended west as far as the Mississippi. Toward the end of this period, the boundaries were more well defined and extended to include the Cherokee lands in the west.[15][16]

Two important maps of the province were produced: one by Edward Moseley in 1733, and another by John Collet in 1770. Edward Mosely was the Surveyor General of the Province of North Carolina before 1710 and 1723 to 1733. He was also the first colonial Treasurer of North Carolina, starting in 1715. He was responsible, with William Byrd II of Virginia Colony, for surveying the boundary between North Carolina and Virginia in 1728. Other maps exist dating to the early period of the Age of Discovery that depict portions of the province, or, more specifically, the coastline of the province along with that of South Carolina.[17]

The ports for which there were Customs Agents in the Province of North Carolina included: Bath, Roanoke, Currituck Precinct, Brunswick (Cape Fear), and Beaufort (Topsail Inlet).[18][17]

There were 52 new towns established in the Province of North Carolina between 1729 and 1775. Major towns during this period included: Bath (chartered in 1705), Brunswick (founded after 1726, destroyed during the American Revolution), Campbellton (established in 1762), Edenton (chartered in 1712), Halifax (chartered in 1757), Hillsborough (1754), New Bern (settled in 1710, chartered in 1723), Salisbury (chartered in 1753), and Wilmington (founded in 1732, chartered in 1739 or 1749). Campbellton and the town of Cross Creek (established in 1765) were combined in 1783 to form the town of Fayetteville. Each of these nine major towns had a single representative in the North Carolina House of Burgesses in 1775.[19]

Government

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1720 | 21,270 | — |

| 1730 | 30,000 | +41.0% |

| 1740 | 51,760 | +72.5% |

| 1750 | 72,984 | +41.0% |

| 1760 | 110,442 | +51.3% |

| 1770 | 197,200 | +78.6% |

| 1780 | 270,138 | +37.0% |

| 1786 | 123,785 | −54.2% |

| Source: 1720–1760;[20] 1786[21] 1770–1780[22] | ||

There were two primary branches of government, the governor and his council and the colonial assembly, called the House of Burgesses. All colonial officials were appointed by either the Lords Proprietor prior to 1728 or The Crown afterwards. The Crown received advice for appointment of the Governor from the Secretary of State for the Southern Department. The Governor was accountable to the Secretary of State and the Board of Trade. The governor was also responsible for commissioning officers and provisioning the provincial militia. Besides the governor, other colonial officials included a secretary, attorney general, surveyor general, the receiver general, Chief Justice, five Customs Collectors for each of the five ports in North Carolina, and a council. The council advised the governor and also served as the upper house of the legislature. Members of the lower house of the legislature, the House of Burgess, were elected from each precinct (called county after 1736) and from districts (also called boroughs or towns, which were large centers of population).[23][24][25][26][27]

Governors of the Province of North Carolina

The eight persons appointed by the Crown to serve as Governor of the province during nine Executive councils included the following:

- Edward Hyde (1712)

- Charles Eden (1714–1722)

- George Burrington (1724–1725), (1731–1734)

- Sir Richard Everard, 4th Baronet (1725–1731)

- Gabriel Johnston (1734–1752)

- Arthur Dobbs (1754–1764)

- William Tryon (1764–1771)

- Josiah Martin (1771–1776)

The last Executive Council

The last Governor of the Province of North Carolina was Josiah Martin, who served from 1771 to 1776. His Executive Council included the following members:[18]

- Samuel Cornell

- William Dry

- George Mercer (Lieutenant Governor)

- James Hasell (Chief Baron of the Exchequer, Acting Governor of the Province of North Carolina in 1771)

- Martin Howard

- Alexander McCulloch

- Robert Palmer

- John Rutherfurd (Receiver General)

- Lewis Henry De Rosset

- John Sampson

- Samuel Strudwick (Clerk)

- Thomas McGuire (Attorney General)

Governor Josiah Martin and the Executive Council issued a proclamation on April 8, 1775 dissolving the Province of North Carolina's General Assembly after the House of Burgesses presented a resolve endorsing the Continental Congress that was to be held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. As the Council met for the last time onboard HMS Cruizer in the Cape Fear River on July 18, 1775, they noted that the "deluded people of this Province" will see their error and return to their allegiance to the King.[18]

Judiciary

The Court Act of 1746 established a supreme court, initially known as the General Court, which sat twice a year at New Bern, consisting of a Chief Justice and three Associate Justices.

- Chief Justices of the Supreme Court [28]

| Incumbent | Tenure | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Took office | Left office | ||

| Christopher Gale | 1703 | 1731 | interrupted by Tobias Knight and Frederick Jones |

| William Smith | 1 Apr 1731 | 1731 | left for England |

| John Palin | 1731 | 18 Oct 1732 | |

| William Little | 18 Oct 1732 | 1734 | died 1734 |

| Daniel Hanmer | 1734 | ||

| William Smith | 1740 | on return from England, died 1740 | |

| John Montgomery | 1740 | ||

| Edward Moseley | 1744 | 1749 | |

| Enoch Hall | 1749 | ||

| Eleazer Allen | 1749 | ||

| James Hasell | name also spelled Hazel or Hazell | ||

| Peter Henley | 1758 | died 1758 | |

| Charles Berry | 1760 | 1766 | committed suicide, 1766 |

| Martin Howard | 1767 | 1775 | Loyalist, forced to leave |

Related events

- Cary's Rebellion (1711)

- Tuscarora War (1711–1715)

- Battle of Cape Fear River (1718)

- King George's War (1744–1748) This war caused disruption at the ports in the Province of North Carolina.[29]

- Granville land grants after 1750

- North-Carolina Gazette First newspaper established in 1751 in New Bern

- Royal Proclamation of 1763 changed the western border of the Province of North Carolina

- Stamp Act 1765

- War of the Regulation (1765–1771), Battle of Alamance (May 16, 1771)

- Tea Act 1773

- North Carolina Light Dragoons Regiment formation in April 1775

Notes

- Craven House, Drury Lane, London was named after William Craven, 1st Earl of Craven (1608–1697). The five story house was demolished in 1809.[4]

References

- Lawson, John (1709). A New Voyage to Carolina. London. p. A2. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Danforth Prince (10 March 2011). Frommer's The Carolinas and Georgia. John Wiley & Sons. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-118-03341-8. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- Lawson, John (1709). A New Voyage to Carolina. London. pp. 239–254. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Wheatley, Cunningham (1891). London Past and Present. Volume 1 A-D. London: John Murray. p. 472. OCLC 832579536. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- Hugh T. Lefler and William S. Powell (1973). Colonial North Carolina: A History. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York.

- Mitchell, Thornton W. (2006). William S. Powell (ed.). Granville Grant and District, Encyclopedia of North Carolina. UNC Press.

- Bishir, Catherine (2005). North Carolina Architecture. UNC Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8078-5624-6.

- David Hackett Fischer, Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America, 1986

- "Table 3a. Persons Who Reported a Single Ancestry Group for Regions, Divisions and States: 1980" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 August 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Table 1. Type of Ancestry Response for Regions, Divisions and States: 1980" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Indentured Servitude in Colonial America"

- Daniel B. Thorp, "Taverns and tavern culture on the southern colonial frontier," Journal of Southern History, Nov 1996, Vol. 62#4 pp. 661–88

- Alan D. Watson, "County Buildings and Other Public Structures in Colonial North Carolina," North Carolina Historical Review, Oct 2005, Vol. 82 Issue 4, pp. 427–463,

- "Chart of his majestie's province of North Carolina with a full description of the coast, 1738." Courtesy of the North Carolina State Department of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.

- Richard A. Stephenson and William S. Powell. "Maps". NCPedia.org. North Carolina Government & Heritage Library. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- Medley, Mary Louise (1976). Anson County Historical Association (ed.). "History of Anson County, North Carolina, 1750-1976". Heritage Printer, Inc., Charlotte, North Carolina. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "New and Correct Map of the Province of North Carolina". digital.lib.ecu.edu. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Lewis, J.D. "Josiah Martin's Executive Council". Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Lewis, J.D. "27th House of Burgess". Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- Purvis, Thomas L. (1999). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Colonial America to 1763. New York: Facts on File. pp. 128–129. ISBN 978-0816025275.

- Purvis, Thomas L. (1995). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Revolutionary America 1763 to 1800. New York: Facts on File. p. 167. ISBN 978-0816025282.

- "Colonial and Pre-Federal Statistics" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. p. 1168.

- "Overview of the Colonial Period". NCPEDIA. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Lewis, J.D. "House of Burgesses of North Carolina". Carolana.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Lewis, J.D. "Executive Councils of Royal Governors". Carolana.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Lewis, J.D. "The Royal Colony Governors". Carolana.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Robinson, Blackwell P. (1963). The Five Royal Governors of North Carolina 1729-1775.

- "History of the Supreme Court of North Carolina" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 21, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- Lewis, J.D. "King Georges War". carolan.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

Further reading

- Cheshire, Jr., Joseph Blount (May 1890). The Church in the Province of North Carolina (Speech). Joint Centennial Convention of the Dioceses of North and East Carolina. Tarboro, N.C. – via Internet Archive.

- Collet, John; Bayly, I. (1770). A Compleat map of North-Carolina from an actual Survey (Map). London: S. Hooper – via University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- "Records of the Executive Council 1664-1734," "Records of the Executive Council 1734-1754," and "Records of the Executive Council 1755-1775," edited by Robert J. Cain, and published by the North Carolina State Archives between 1984 and 1994.

External links

- Colonial Period at NCpedia (ncpedia.org)

.svg.png)