Proto-language

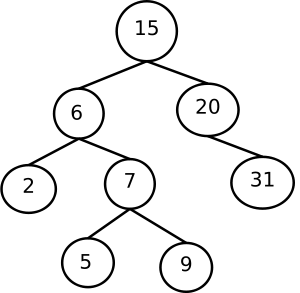

A proto-language, in the tree model of historical linguistics, is a language, usually hypothetical or reconstructed, and usually unattested, from which a number of attested known languages are believed to have descended by evolution, forming a language family. In the family tree metaphor, a proto-language can be called a mother language.

In the strict sense, a proto-language is the most recent common ancestor of a language family, immediately before the family started to diverge into the attested daughter languages. It is therefore equivalent with the ancestral language or parental language of a language family.[1]

Moreover, a group of languages (such as a dialect cluster) which are not considered separate languages (for whichever reasons) may also be described as descending from a unitary proto-language.

Occasionally, the German term Ursprache (from Ur- "primordial, original" and Sprache "language", pronounced [ˈuːɐ̯ʃpʁaːxə]) is used instead.

Definition and verification

Typically, the proto-language is not known directly. It is by definition a linguistic reconstruction formulated by applying the comparative method to a group of languages featuring similar characteristics.[2] The tree is a statement of similarity and a hypothesis that the similarity results from descent from a common language.

The comparative method, a process of deduction, begins from a set of characteristics, or characters, found in the attested languages. If the entire set can be accounted for by descent from the proto-language, which must contain the proto-forms of them all, the tree, or phylogeny, is regarded as a complete explanation and by Occam's razor, is given credibility. More recently such a tree has been termed "perfect" and the characters labelled "compatible".

No trees but the smallest branches are ever found to be perfect, in part because languages also evolve through horizontal transfer with their neighbours. Typically, credibility is given to the hypotheses of highest compatibility. The differences in compatibility must be explained by various applications of the wave model. The level of completeness of the reconstruction achieved varies, depending on how complete the evidence is from the descendant languages and on the formulation of the characters by the linguists working on it. Not all characters are suitable for the comparative method. For example, lexical items that are loans from a different language do not reflect the phylogeny to be tested, and if used will detract from the compatibility. Getting the right dataset for the comparative method is a major task in historical linguistics.

Some universally accepted proto-languages are Proto-Indo-European, Proto-Uralic, and Proto-Dravidian.

In a few fortuitous instances, which have been used to verify the method and the model (and probably ultimately inspired it), a literary history exists from as early as a few millennia ago, allowing the descent to be traced in detail. The early daughter languages, and even the proto-language itself, may be attested in surviving texts. For example, Latin is the proto-language of the Romance language family, which includes such modern languages as French, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian, Catalan and Spanish. Likewise, Proto-Norse, the ancestor of the modern Scandinavian languages, is attested, albeit in fragmentary form, in the Elder Futhark. Although there are no very early Indo-Aryan inscriptions, the Indo-Aryan languages of modern India all go back to Vedic Sanskrit (or dialects very closely related to it), which has been preserved in texts accurately handed down by parallel oral and written traditions for many centuries.

The first person to offer systematic reconstructions of an unattested proto-language was August Schleicher; he did so for Proto-Indo-European in 1861.[3]

Proto-X vs. Pre-X

Normally, the term "Proto-X" refers to the last common ancestor of a group of languages, occasionally attested but most commonly reconstructed through the comparative method, as with Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Germanic. An earlier stage of a single language X, reconstructed through the method of internal reconstruction, is termed "Pre-X", as in Pre-Old Japanese.[4] It is also possible to apply internal reconstruction to a proto-language, obtaining a pre-proto-language, such as Pre-Proto-Indo-European.[5]

Both prefixes are sometimes used for an unattested stage of a language without reference to comparative or internal reconstruction. "Pre-X" is sometimes also used for a postulated substratum, as in the Pre-Indo-European languages believed to have been spoken in Europe and South Asia before the arrival there of Indo-European languages.

When multiple historical stages of a single language exist, the oldest attested stage is normally termed "Old X" (e.g. Old English and Old Japanese). In other cases, such as Old Irish and Old Norse, the term refers to the language of the oldest known significant texts. Each of these languages has an older stage (Primitive Irish and Proto-Norse respectively) that is attested only fragmentarily.

Accuracy

There are no objective criteria for the evaluation of different reconstruction systems yielding different proto-languages. Many researchers concerned with linguistic reconstruction agree that the traditional comparative method is an "intuitive undertaking."[6]

The bias of the researchers regarding the accumulated implicit knowledge can also lead to erroneous assumptions and excessive generalization. Kortlandt (1993) offers several examples in where such general assumptions concerning "the nature of language" hindered research in the field of historical linguistics. Linguists make personal judgements on how they consider "natural" for a language to change, and "[as] a result, our reconstructions tend to have a strong bias toward the average language type known to the investigator." Such an investigator finds him- or herself blinkered by their own linguistic frame of reference.

The advent of the wave model raised new issues in the domain of linguistic reconstruction, causing the reevaluation of old reconstruction systems and depriving the proto-language of its "uniform character." This is evident in Karl Brugmann's skepticism that the reconstruction systems could ever reflect a linguistic reality.[7] Ferdinand de Saussure would even express a more certain opinion, completely rejecting a positive specification of the sound values of reconstruction systems.[8]

In general, the issue of the nature of proto-language remains unresolved, with linguists generally taking either the realist or abstractionist position. Even the widely studied proto-languages, such as Proto-Indo-European, have drawn criticism for being outliers typologically with respect to the reconstructed phonemic inventory. The alternatives such as glottalic theory, despite representing a typologically less rare system, have not gained wider acceptance, with some researchers even suggesting the use of indexes to represent the disputed series of plosives. On the other end of spectrum, Pulgram (1959:424) suggests that Proto-Indo-European reconstructions are just "a set of reconstructed formulae" and "not representative of any reality". In the same vein Julius Pokorny in his study on Indo-European claims that the linguistic term IE parent language is merely an abstraction that does not exist in reality, and it should be understood as consisting of dialects possibly dating back to the paleolithic era, in which these very dialects formed the linguistic structure of the IE language group.[9] In his view, Indo-European is solely a system of isoglosses which bound together dialects which were operationalized by various tribes, from which the historically attested Indo-European languages emerged.[9]

See also

Notes

- Bruce M. Rowe, Diane P. Levine (2015). A Concise Introduction to Linguistics. Routledge. pp. 340–341. ISBN 1317349288. Retrieved 26 January 2017.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Koerner, E F K (1999), Linguistic historiography: projects & prospects, Amsterdam studies in the theory and history of linguistic science; Ser. 3, Studies in the history of the language sciences, Amsterdam [u.a.]: J. Benjamins, p. 109,

First, the historical linguist does not reconstruct a language (or part of the language) but a model which represents or is intended to represent the underlying system or systems of such a language.

- Lehmann 1993, p. 26.

- Campbell, Lyle (2013). Historical Linguistics: An Introduction (3rd ed.). Edinburgh University Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-7486-4601-2.

- Campbell (2013), p. 211.

- Schwink, Frederick W.: Linguistic Typology, Universality and the Realism of Reconstruction, Washington 1994. "Part of the process of “becoming” a competent Indo-Europeanist has always been recognized as coming to grasp “intuitively” concepts and types of changes in language so as to be able to pick and choose between alternative explanations for the history and development of specific features of the reconstructed language and its offspring.""

- Brugmann & Delbrück (1904:25)

- Saussure (1969:303)

- Pokorny (1953:79–80)

References

- Lehmann, Winfred P. (1993), Theoretical Bases of Indo-European Linguistics, London, New York: Taylor & Francis Group (Routledge)

- Schleicher, August (1861–1862), Compendium der vergleichenden Grammatik der indogermanischen Sprachen: 2 volumes, Weimar: H. Boehlau (Reprint: Minerva GmbH, Wissenschaftlicher Verlag), ISBN 3-8102-1071-4

- Kortlandt, Frederik (1993), General Linguistics and Indo-European Reconstruction (PDF) (revised text of a paper read at the Institute of general and applied linguistics, University of Copenhagen, on December 2, 1993)

- Brugmann, Karl; Delbrück, Berthold (1904), Kurze vergleichende Grammatik der indogermanischen Sprachen (in German), Strassburg

- Saussure, Ferdinand de (1969), Cours de linguistique générale [Course in General Linguistics] (in French), Paris

- Pulgram, Ernst (1959), "Proto-Indo-European Reality and Reconstruction", Language, 35 (Jul.–Sept.): 421–426, doi:10.2307/411229

- Pokorny, Julius (1953), Allgemeine und Vergleichende Sprachwissenschaft – Indogermanistik [General and Comparative Linguistics - Indo-European Studies], 2, Bern: A. Francke AG Verlag, pp. 79–80