Project-based learning

Project-based learning (PBL) is a student-centered pedagogy that involves a dynamic classroom approach in which it is believed that students acquire a deeper knowledge through active exploration of real-world challenges and problems.[1] Students learn about a subject by working for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to a complex question, challenge, or problem.[2] It is a style of active learning and inquiry-based learning. PBL contrasts with paper-based, rote memorization, or teacher-led instruction that presents established facts or portrays a smooth path to knowledge by instead posing questions, problems or scenarios.[3]

History

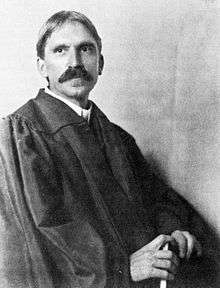

John Dewey is recognized as one of the early proponents of project-based education or at least its principles through his idea of "learning by doing".[4] In My Pedagogical Creed (1897) Dewey enumerated his beliefs including the view that "the teacher is not in the school to impose certain ideas or to form certain habits in the child, but is there as a member of the community to select the influences which shall affect the child and to assist him in properly responding to these.[5] For this reason, he promoted the so-called expressive or constructive activities as the centre of correlation.[5] Educational research has advanced this idea of teaching and learning into a methodology known as "project-based learning". William Heard Kilpatrick built on the theory of Dewey, who was his teacher, and introduced the project method as a component of Dewey's problem method of teaching.[6]

Some scholars (e.g. James G. Greeno) also associated project-based learning with Jean Piaget's "situated learning" perspective[7] and constructivist theories. Piaget advocated an idea of learning that does not focus on the memorization. Within his theory, project-based learning is considered a method that engages students to invent and to view learning as a process with a future instead of acquiring knowledge base as a matter of fact.[8]

Further developments to the project-based education as a pedagogy later drew from the experience- and perception-based theories on education proposed by theorists such as Jan Comenius, Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, and Maria Montessori, among others.[6]

Concept

Thomas Markham (2011) describes project-based learning (PBL) thus: "PBL integrates knowing and doing. Students learn knowledge and elements of the core curriculum, but also apply what they know to solve authentic problems and produce results that matter. PBL students take advantage of digital tools to produce high quality, collaborative products. PBL refocuses education on the student, not the curriculum—a shift mandated by the global world, which rewards intangible assets such as drive, passion, creativity, empathy, and resiliency. These cannot be taught out of a textbook, but must be activated through experience."[9]

Blumenfeld et al. elaborate on the processes of PBL: "Project-based learning is a comprehensive perspective focused on teaching by engaging students in investigation. Within this framework, students pursue solutions to nontrivial problems by asking and refining questions, debating ideas, making predictions, designing plans and/or experiments, collecting and analyzing data, drawing conclusions, communicating their ideas and findings to others, asking new questions, and creating artifacts."[10] The basis of PBL lies in the authenticity or real-life application of the research. Students working as a team are given a "driving question" to respond to or answer, then directed to create an artifact (or artifacts) to present their gained knowledge. Artifacts may include a variety of media such as writings, art, drawings, three-dimensional representations, videos, photography, or technology-based presentations.

Proponents of project-based learning cite numerous benefits to the implementation of its strategies in the classroom – including a greater depth of understanding of concepts, broader knowledge base, improved communication and interpersonal/social skills, enhanced leadership skills, increased creativity, and improved writing skills. Another definition of project-based learning includes a type of instruction, where students work together to solve real-world problems in their schools and communities. Successful problem-solving often requires students to draw on lessons from several disciplines and apply them in a very practical way. The promise of seeing a very real impact becomes the motivation for learning.[11]

In Peer Evaluation in Blended Team Project-Based Learning: What Do Students Find Important?, Hye-Jung & Cheolil (2012) describe "social loafing" as a negative aspect of collaborative learning. Social loafing may include insufficient performances by some team members as well as a lowering of expected standards of performance by the group as a whole to maintain congeniality amongst members. These authors said that because teachers tend to grade the finished product only, the social dynamics of the assignment may escape the teacher's notice.[12]

Structure

Project-based learning emphasizes learning activities that are long-term, interdisciplinary and student-centered. Unlike traditional, teacher-led classroom activities, students often must organize their own work and manage their own time in a project-based class. Project-based instruction differs from traditional inquiry by its emphasis on students' collaborative or individual artifact construction to represent what is being learned.

Project-based learning also gives students the opportunity to explore problems and challenges that have real-world applications, increasing the possibility of long-term retention of skills and concepts.[13]

Elements

The core idea of project-based learning is that real-world problems capture students' interest and provoke serious thinking as the students acquire and apply new knowledge in a problem-solving context. The teacher plays the role of facilitator, working with students to frame worthwhile questions, structuring meaningful tasks, coaching both knowledge development and social skills, and carefully assessing what students have learned from the experience. Typical projects present a problem to solve (What is the best way to reduce the pollution in the schoolyard pond?) or a phenomenon to investigate (What causes rain?). PBL replaces other traditional models of instruction such as lecture, textbook-workbook driven activities and inquiry as the preferred delivery method for key topics in the curriculum. It is an instructional framework that allows teachers to facilitate and assess deeper understanding rather than stand and deliver factual information. PBL intentionally develops students' problem solving and creative making of products to communicate deeper understanding of key concepts and mastery of 21st Century essential learning skills such as critical thinking. Students become active digital researchers and assessors of their own learning when teachers guide student learning so that students learn from the project making processes. In this context, PBLs are units of self-directed learning from students' doing or making throughout the unit. PBL is not just "an activity" (project) that is stuck on the end of a lesson or unit.

Comprehensive project-based learning:

- is organized around an open-ended driving question or challenge.

- creates a need to know essential content and skills.

- requires inquiry to learn and/or create something new.

- requires critical thinking, problem solving, collaboration, and various forms of communication, often known as 21st century skills.

- allows some degree of student voice and choice.

- incorporates feedback and revision.

- results in a publicly presented product or performance.[14]

Examples

Although projects are the primary vehicle for instruction in project-based learning, there are no commonly shared criteria for what constitutes an acceptable project. Projects vary greatly in the depth of the questions explored, the clarity of the learning goals, the content and structure of the activity, and guidance from the teacher. The role of projects in the overall curriculum is also open to interpretation. Projects can guide the entire curriculum (more common in charter or other alternative schools) or simply consist of a few hands-on activities. They might be multidisciplinary (more likely in elementary schools) or single-subject (commonly science and math). Some projects involve the whole class, while others are done in small groups or individually. For example, Perrault and Albert[15] report the results of a PBL assignment in a college setting surrounding creating a communication campaign for the campus' sustainability office, finding that after project completion in small groups that the students had significantly more positive attitudes toward sustainability than prior to working on the project.

When PBL is used with 21st century tools/skills, students are expected to use technology in meaningful ways to help them investigate, collaborate, analyze, synthesize and present their learning. The term IPBL (Interdisciplinary PBL) has also been used to reflect a pedagogy where an emphasis on technology and/or an interdisciplinary approach has been included.

An example of a school that utilizes a project-based learning curriculum is Think Global School. In each country Think Global School visits, students select an interdisciplinary, project-based learning module designed to help them answer key questions about the world around them. These projects combine elements of global studies, the sciences, and literature, among other courses. Projects from past years have included recreating Homer's The Odyssey by sailing across Greece and exploring the locations and concepts central to the epic poem, and while in Kerala, India, students participated in a project-based learning module centered around blending their learning and travels into a mock business venture. The interdisciplinary project was designed to enable students to engage in the key areas of problem solving, decision making and communication — all framed by the demanding parameters of a "Shark Tank", or "Dragon's Den" style competition.

Another example of applied PBL is Muscatine High School, located in Muscatine, Iowa. The school started the G2 (Global Generation Exponential Learning) which consists of middle and high school "Schools within Schools" that deliver the four core subject areas. At the high school level, activities may include making water purification systems, investigating service learning, or creating new bus routes. At the middle school level, activities may include researching trash statistics, documenting local history through interviews, or writing essays about a community scavenger hunt. Classes are designed to help diverse students become college and career ready after high school.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has provided funding to start holistic PBL schools across the United States. Notable funded organizations include,

- EdVisions Schools

- Envision Schools

- New Tech Network

- North Bay Academy of Communication and Design

- Raisbeck Aviation High School[16]

Another example is Manor New Technology High School, a public high school that since opening in 2007 is a 100 percent project-based instruction school. Students average 60 projects a year across subjects. It is reported that 98 percent of seniors graduate, 100 percent of the graduates are accepted to college, and fifty-six percent of them have been the first in their family to attend college.[17]

Outside of the United States, the European Union has also providing funding for project-based learning projects within the Lifelong Learning Programme 2007–2013. In China, PBL implementation has primarily been driven by International School offerings,[18] although public schools use PBL as a reference for Chinese Premier Ki Keqiang's mandate for schools to adopt Maker Education,[19] in conjunction with micro-schools like Moonshot Academy and ETU, and maker education spaces such as SteamHead.[20]

According to Terry Heick on his blog, Teach Thought, there are three types of project-based learning. The first is Challenge-Based Learning/Problem-Based Learning, the second is Place-Based Education, and the third is Activity-Based learning. Challenge-Based Learning is "an engaging multidisciplinary approach to teaching and learning that encourages students to leverage the technology they use in their daily lives to solve real-world problems through efforts in their homes, schools and communities." Place-based Education "immerses students in local heritage, cultures, landscapes, opportunities and experiences; uses these as a foundation for the study of language arts, mathematics, social studies, science and other subjects across the curriculum, and emphasizes learning through participation in service projects for the local school and/or community." Activity-Based Learning takes a kind of constructivist approach, the idea being students constructing their own meaning through hands-on activities, often with manipulatives and opportunities to. As a private school provider Nobel Education Network combines PBL with the International Baccalaureate as a central pillar of their strategy.[21]

Roles

PBL relies on learning groups. Student groups determine their projects, and in so doing, they engage student voice by encouraging students to take full responsibility for their learning. This is what makes PBL constructivist. Students work together to accomplish specific goals.

When students use technology as a tool to communicate with others, they take on an active role vs. a passive role of transmitting the information by a teacher, a book, or broadcast. The student is constantly making choices on how to obtain, display, or manipulate information. Technology makes it possible for students to think actively about the choices they make and execute. Every student has the opportunity to get involved, either individually or as a group.

The instructor's role in Project-Based Learning is that of a facilitator. They do not relinquish control of the classroom or student learning, but rather develop an atmosphere of shared responsibility. The instructor must structure the proposed question/issue so as to direct the student's learning toward content-based materials. The instructor must regulate student success with intermittent, transitional goals to ensure student projects remain focused and students have a deep understanding of the concepts being investigated. The students are held accountable to these goals through ongoing feedback and assessments. The ongoing assessment and feedback are essential to ensure the student stays within the scope of the driving question and the core standards the project is trying to unpack. According to Andrew Miller of the Buck Institute of Education, "In order to be transparent to parents and students, you need to be able to track and monitor ongoing formative assessments that show work toward that standard."[22] The instructor uses these assessments to guide the inquiry process and ensure the students have learned the required content. Once the project is finished, the instructor evaluates the finished product and the learning that it demonstrates.

The student's role is to ask questions, build knowledge, and determine a real-world solution to the issue/question presented. Students must collaborate, expanding their active listening skills and requiring them to engage in intelligent, focused communication, therefore allowing them to think rationally about how to solve problems. PBL forces students to take ownership of their success.

Outcomes

More important than learning science, students need to learn to work in a community, thereby taking on social responsibilities. The most significant contributions of PBL have been in schools languishing in poverty stricken areas; when students take responsibility, or ownership, for their learning, their self-esteem soars. It also helps to create better work habits and attitudes toward learning. In standardized tests, languishing schools have been able to raise their testing grades a full level by implementing PBL. Although students do work in groups, they also become more independent because they are receiving little instruction from the teacher. With Project-Based Learning students also learn skills that are essential in higher education. The students learn more than just finding answers, PBL allows them to expand their minds and think beyond what they normally would. Students have to find answers to questions and combine them using critically thinking skills to come up with answers.

PBL is significant to the study of (mis-)conceptions; local concepts and childhood intuitions that are hard to replace with conventional classroom lessons. In PBL, project science is the community culture; the student groups themselves resolve their understandings of phenomena with their own knowledge building. Technology allows them to search in more useful ways, along with getting more rapid results.

Blumenfeld & Krajcik (2006) cite studies that show students in project-based learning classrooms get higher scores than students in traditional classroom.[23]

Opponents of Project Based Learning warn against negative outcomes primarily in projects that become unfocused and tangential arguing that underdeveloped lessons can result in the wasting of precious class time. No one teaching method has been proven more effective than another. Opponents suggest that narratives and presentation of anecdotal evidence included in lecture-style instruction can convey the same knowledge in less class time. Given that disadvantaged students generally have fewer opportunities to learn academic content outside of school, wasted class time due to an unfocused lesson presents a particular problem. Instructors can be deluded into thinking that as long as a student is engaged and doing, they are learning. Ultimately it is cognitive activity that determines the success of a lesson. If the project does not remain on task and content driven the student will not be successful in learning the material. The lesson will be ineffective. A source of difficulty for teachers includes, "Keeping these complex projects on track while attending to students' individual learning needs requires artful teaching, as well as industrial-strength project management."[24] Like any approach, Project Based Learning is only beneficial when applied successfully.

Problem-based learning is a similar pedagogic approach, however, problem-based approaches structure students' activities more by asking them to solve specific (open-ended) problems rather than relying on students to come up with their own problems in the course of completing a project. Another seemingly similar approach is quest-based learning; unlike project-based learning, in questing, the project is determined specifically on what students find compelling (with guidance as needed), instead of the teacher being primarily responsible for forming the essential question and task.[25]

A meta-analysis conducted by Purdue University found that when implemented well, PBL can increase long-term retention of material and replicable skill, as well as improve teachers' and students' attitudes towards learning.[26]

Overcoming obstacles and criticisms

A frequent criticism of PBL is that when students work in groups some will "slack off" or sit back and let the others do all the work. Anne Shaw recommends that teachers always build into the structure of the PBL curriculum an organizational strategy known as Jigsaw and Expert Groups. This structure forces students to be self-directed, independent and to work interdependently.

This means that the class is assigned (preferably randomly, by lottery) to Expert Groups. Each of the Expert Groups is then assigned to deeply study one particular facet of the overall project. For example, a class studying about environmental issues in their community may be divided into the following Expert Groups:

- Air

- Land

- Water

- Human impact on the environment

Each Expert Group is tasked with studying the materials for their group, taking notes, then preparing to teach what they learned to the rest of the students in the class. To do so, the class will "jigsaw", thus creating Jigsaw Groups. The Jigsaw Groups in the above example would each be composed of one representative from each of the Expert Groups, so each Jigsaw Group would include:

- One expert on Air

- One expert on Land

- One expert on Water

- One expert on "Human impact on the environment"

Each of these experts would then take turns teaching the others in the group. Total interdependence is assured. No one can "slack off" because each student is the only person in the group with that "piece" of the information. Another benefit is that the students must have learned the concepts, skills and information well enough to be able to teach it and must be able to assess (not grade) their own learning and the learning of their peers. This forces a much deeper learning experience.

Anne Shaw recommends that when students are teaching each other they also participate collaboratively in creating a concept map as they teach each other. This adds a significant dimension to the thinking and the learning. The students may build upon this map each time they Jigsaw. If a project is scheduled to last over the time period of six weeks the students may meet in their Expert Groups twice a week, and then Jigsaw twice a week, building upon their learning and exploration of the topics over time.

Once all the experts have taught each other, the Jigsaw Group then designs and creates a product to demonstrate what they now know about all four aspects of the PBL unit – air, land, water, human's impact. Performance-based products may include a wide range of possibilities such as dioramas, skits, plays, debates, student-produced documentaries, web sites, Glogsters, VoiceThreads, games (digital or not), presentations to members of the community (such as the City Council or a community organization), student-produced radio or television program, a student-organized conference, a fair, a film festival.

Students are assessed in two ways:

- Individual assessments for each student – may include research notes, teaching prep notes and teacher observation. Other assessments may include those assigned by the teacher, for example, each student in the class must write an individual research paper for a topic of their choice from within the theme of the overall PBL.

- Group assessments – each Jigsaw group creates and presents their product, preferably to an audience other than the teacher or their class.[27]

Criticism

One concern is that PBL may be inappropriate in mathematics, the reason being that mathematics is primarily skill-based at the elementary level. Transforming the curriculum into an over-reaching project or series of projects does not allow for necessary practice of particular mathematical skills. For instance, factoring quadratic expressions in elementary algebra requires extensive repetition .

On the other hand, a teacher could integrate a PBL approach into the standard curriculum, helping the students see some broader contexts where abstract quadratic equations may apply. For example, Newton's law implies that tossed objects follow a parabolic path, and the roots of the corresponding equation correspond to the starting and ending locations of the object.

Another criticism of PBL is that measures that are stated as reasons for its success are not measurable using standard measurement tools, and rely on subjective rubrics for assessing results.

In PBL there is also a certain tendency for the creation of the final product of the project to become the driving force in classroom activities. When this happens, the project can lose its content focus and be ineffective in helping students learn certain concepts and skills. For example, academic projects that culminate in an artistic display or exhibit may place more emphasis on the artistic processes involved in creating the display than on the academic content that the project is meant to help students learn.

See also

- Da Vinci Schools

- Dos Pueblos Engineering Academy

- Energetic Learning Campus (North Peace Secondary School)

- Design-based learning

- Experiential education

- Fremdsprachen und Hochschule (German academic journal)

- Hyper Island

- Inquiry-based learning

- John Dewey Academy of Learning

- Khan Lab School[28]

- Minnesota State University, Mankato Masters Degree in Experiential Education

- New Technology High School

- North Bay Academy of Communication and Design

- Northwoods Community Secondary School

- Phenomenon-based learning

- Problem-based learning

- Challenge-based learning

- Reggio Emilia approach

- Student voice

- Sudbury school

- TAGOS Leadership Academy

- Teaching for social justice

- Valley New School

References

- Project-Based Learning, Edutopia, March 14, 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-15

- What is PBL? Buck Institute for Education. Retrieved 2016-03-15

- Yasseri, Dar; Finley, Patrick M.; Mayfield, Blayne E.; Davis, David W.; Thompson, Penny; Vogler, Jane S. (2018-06-01). "The hard work of soft skills: augmenting the project-based learning experience with interdisciplinary teamwork". Instructional Science. 46 (3): 457–488. doi:10.1007/s11251-017-9438-9. ISSN 1573-1952.

- Bender, William N. (2012). Project-Based Learning: Differentiating Instruction for the 21st Century. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-4522-7927-5.

- John Dewey, Education and Experience, 1938/1997. New York. Touchstone.

- Beckett, Gulbahar; Slater, Tammy (2019). Global Perspectives on Project-Based Language Learning, Teaching, and Assessment: Key Approaches, Technology Tools, and Frameworks. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-78695-2.

- Greeno, J. G. (2006). Learning in activity. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 79-96). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Sarrazin, Natalie R. (2018). Problem-Based Learning in the College Music Classroom. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-26522-5.

- Markham, T. (2011). Project Based Learning. Teacher Librarian, 39(2), 38-42.

- Blumenfeld et al 1991, EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGIST, 26(3&4) 369-398 "Motivating Project-Based Learning: Sustaining the Doing, Supporting the Learning." Phyllis C. Blumenfeld, Elliot Soloway, Ronald W. Marx, Joseph S. Krajcik, Mark Guzdial, and Annemarie Palincsar.

- "Education World".

- Hye-Jung Lee1, h., & Cheolil Lim1, c. (2012). Peer Evaluation in Blended Team Project-Based Learning: What Do Students Find Important?. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 15(4), 214-224.

- Crane, Beverley (2009). Using Web 2.0 Tools in the K-12 Classroom. New York: Neal-Schuman Publishers. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-55570-653-1.

- http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational_leadership/sept10/vol68/num01/Seven_Essentials_for_Project-Based_Learning.aspx

- Perrault, Evan K.; Albert, Cindy A. (2017-10-04). "Utilizing project-based learning to increase sustainability attitudes among students". Applied Environmental Education & Communication. 0 (2): 96–105. doi:10.1080/1533015x.2017.1366882. ISSN 1533-015X.

- Aviation High students land in their new school, Seattle Times, October 16, 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-29

- Makes Project-Based Learning a Success?. Retrieved 2013-10-29

- . Larmer, John (2018)

- Xin Hua News, referenced 2017.

- Heick, Terry (August 2, 2018). "3 Types Of Project-Based Learning Symbolize Its Evolution"

- Miller, Andrew. "Edutopia". © 2013 The George Lucas Educational Foundation. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Sawyer, R. K. (2006) The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- "Projects and Partnerships Build a Stronger Future - Edutopia". edutopia.org.

- Alcock, Marie; Michael Fisher; Allison Zmuda (2018). The Quest for Learning: How to Maximize Student Engagement. Bloomington: Solution Tree.

- Strobel, Johannes; van Barneveld, Angela (24 March 2009). "When is PBL More Effective? A Meta-synthesis of Meta-analyses Comparing PBL to Conventional Classrooms". Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning. 3 (1). doi:10.7771/1541-5015.1046.

- 21st Century Schools. Retrieved 2016-03-15

- "Project-Based Learning". Khan Lab School.

Notes

- John Dewey, Education and Experience, 1938/1997. New York. Touchstone.

- Hye-Jung Lee1, h., & Cheolil Lim1, c. (2012). Peer Evaluation in Blended Team Project-Based Learning: What Do Students Find Important?. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 15(4), 214-224.

- Markham, T. (2011). Project Based Learning. Teacher Librarian, 39(2), 38-42.

- Blumenfeld et al. 1991, EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGIST, 26(3&4) 369-398 "Motivating Project-Based Learning: Sustaining the Doing, Supporting the Learning." Phyllis C. Blumenfeld, Elliot Soloway, Ronald W. Marx, Joseph S. Krajcik, Mark Guzdial, and Annemarie Palincsar.

- Sawyer, R. K. (2006), The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Buck Institute for Education (2009). PBL Starter Kit: To-the-Point Advice, Tools and Tips for Your First Project. Introduction chapter free to download at: https://web.archive.org/web/20101104022305/http://www.bie.org/tools/toolkit/starter

- Buck Institute for Education (2003). Project Based Learning Handbook: A Guide to Standards-Focused Project Based Learning for Middle and High School Teachers. Introduction chapter free to download at: https://web.archive.org/web/20110122135305/http://www.bie.org/tools/handbook

- Barron, B. (1998). Doing with understanding: Lessons from research on problem- and project-based learning. Journal of the Learning Sciences. 7 (3&4), 271-311.

- Blumenfeld, P.C. et al. (1991). Motivating project-based learning: sustaining the doing, supporting the learning. Educational Psychologist, 26, 369-398.

- Boss, S., & Krauss, J. (2007). Reinventing project-based learning: Your field guide to real-world projects in the digital age. Eugene, OR: International Society for Technology in Education.

- Falk, B. (2008). Teaching the way children learn. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Katz, L. and Chard, S.C.. (2000) Engaging Children's Minds: The Project Approach (2d Edition), Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.

- Keller, B. (2007, September 19). No Easy Project. Education Week, 27(4), 21-23. Retrieved March 25, 2008, from Academic Search Premier database.

- Knoll, M. (1997). The project method: its origin and international development. Journal of Industrial Teacher Education 34 (3), 59-80.

- Knoll, M. (2012). "I had made a mistake": William H. Kilpatrick and the Project Method. Teachers College Record 114 (February), 2, 45 pp.

- Knoll, M. (2014). Project Method. Encyclopedia of Educational Theory and Philosophy, ed. C.D. Phillips. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Vol. 2., pp. 665–669.

- Shapiro, B. L. (1994). What Children Bring to Light: A Constructivist Perspective on Children's Learning in Science; New York. Teachers College Press.

- Helm, J. H., Katz, L. (2001). Young investigators: The project approach in the early years. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Mitchell, S., Foulger, T. S., & Wetzel, K., Rathkey, C. (February, 2009). The negotiated project approach: Project-based learning without leaving the standards behind. Early Childhood Education Journal, 36(4), 339-346.

- Polman, J. L. (2000). Designing project-based science: Connecting learners through guided inquiry. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Reeves, Diane Lindsey STICKY LEARNING. Raleigh, North Carolina: Bright Futures Press, 2009. .

- Foulger, T.S. & Jimenez-Silva, M. (2007). "Enhancing the writing development of English learners: Teacher perceptions of common technology in project-based learning". Journal of Research on Childhood Education, 22(2), 109-124.

- Shaw, Anne. 21st Century Schools.

- Wetzel, K., Mitchell-Kay, S., & Foulger, T. S., Rathkey, C. (June, 2009). Using technology to support learning in a first grade animal and habitat project. International Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning.

- Heick, Terry. (2013). 3 Types of Project-Based Learning Symbolize Its Evolution. Available at http://www.teachthought.com/learning/5-types-of-project-based-learning-symbolize-its-evolution/

External links

- Project Based Learning for the 21st century – From The Buck Institute for Education

- North Lawndale College Prep High School's Interdisciplinary Projects – Vertically aligned, high-bar problem- and project-based learning, 9-12, on Chicago's west side.

- Ten Tips for Assessing Project-Based Learning – From Edutopia by The George Lucas Educational Foundation.

- Project-Based Learning and High Standards at Shutesbury Elementary School – From Edutopia by The George Lucas Educational Foundation.

- Intel Teach Elements: Project-Based Approaches is a free, online professional development course that explores project-based learning.

- Project Work in (English) Language Teaching provides a practical guide to running a successful 30-hour (15-lesson) short film project in English with (pre-)intermediate students: planning, lessons, evaluation, deliverables, samples and experiences, plus ideas for other projects.

- Project Based Freelance Initiative Connects college students with local, national & global businesses as a way for students to gain real world experience via project based learning freelance. Project based learning "tasCerts" have a qualified mentor to ensure projects meet the required objectives of the businesses involved.