Portuguese cuisine

Portuguese cuisine was first recorded in the seventeenth century, with regional recipes establishing themselves in the nineteenth century. Culinária Portuguesa, by António-Maria De Oliveira Bello, better known as Olleboma; was the first ‘Portuguese-only’ recipe book published in 1936.[1] Despite being relatively restricted to an Atlantic, Celtic sustenance,[2][3] the Portuguese cuisine also has strong French[4] and Mediterranean[5] influences.

The influence of Portugal's former colonial possessions is also notable, especially in the wide variety of spices used. These spices include piri piri (small, fiery chili peppers), white pepper, black pepper, paprika, clove, allspice, cumin, nutmeg, and saffron are used in meat, fish or multiple savoury dishes. Homemade hot red pepper paste made of malagueta peppers is very commonly used in the various dishes of the Azores islands, along with other spices. Cinnamon, vanilla, cardamom, aniseed, clove and allspice are used in many traditional desserts and sometimes in savoury dishes.

Garlic and onions are widely used, as are herbs, such as bay leaf, parsley, oregano, thyme, mint, marjoram, rosemary and coriander being the most prevalent.

Olive oil is one of the bases of Portuguese cuisine, which is used both for cooking and flavouring raw meals. This has led to a unique classification of olive oils in Portugal, depending on their acidity: 1.5 degrees is only for cooking with (virgin olive oil), anything lower than 1 degree is good for dousing over fish, potatoes and vegetables (extra virgin). 0.7, 0.5 or even 0.3 degrees are for those who do not enjoy the taste of olive oil at all, or who wish to use it in, say, a mayonnaise or sauce where the taste is meant to be disguised.

Portuguese dishes include meats (pork, beef, poultry mainly also game (hunting) and others), seafood (fish, crustaceans such as lobster, crab, shrimps, prawns, octopus, and molluscs such as scallops, clams and barnacles), vegetables and legumes (a variety of soups) and desserts (cakes being the most numerous). Portuguese often consume bread with their meals and there are numerous varieties of traditional fresh breads like broa[6][7][8] which may also have regional and national variations within the countries under Lusophone or Galician influence.[9][10]

Meals

A Portuguese traditional breakfast often consists of fresh bread, with butter, ham, cheese or jam, accompanied by coffee, milk, tea or hot chocolate. A small espresso coffee (sometimes called a bica or cimbalino after the spout of the coffee machine) is a very popular beverage had during breakfast, which is enjoyed at home or at the many cafés in towns and cities throughout Portugal. Sweet pastries are also very popular, as well as breakfast cereal, mixed with milk or yogurt and fruit.

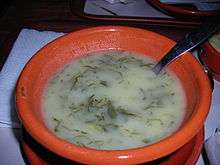

Lunch is served between noon and 2 o'clock, typically around 1 o'clock and dinner is generally served at around 8 o'clock. There are three main courses, with lunch and dinner often including a soup. The most common Portuguese soup is caldo verde (kale soup)[11], which consists of a base of pureed potato, onion and garlic, to which thinly shredded kale[12] leaves are then added. Chunks of chouriço (a smoked or spiced Portuguese sausage) are often added as well, but may be omitted, thereby making the soup fully vegan. This soup is served in a tigela, a traditional earthenware bowl.[13]

Among fish recipes, salted dried cod (bacalhau)[14] dishes are pervasive. There are apparently 365 different bacalhau recipes in Portugal, one for each day of the year.[15] The most typical desserts are arroz doce (rice pudding decorated with cinnamon) and caramel custard. There is also a wide variety of cheeses made from the milk of sheep, goats or cows. These cheeses can also contain a mixture of different kinds of milk. The most famous are queijo da serra from the region of Serra da Estrela, Queijo São Jorge from the island of São Jorge, Castelo Branco[16] Queijo Rabaçal, Requeijão.[17]

A very popular pastry is the pastel de nata,[18] a small custard tart often sprinkled with cinnamon. This pastry is now famous in different countries worldwide, including the UK where it is known as nata or Portuguese custard tart.[19][20]

Fish and seafood

.jpg)

Portugal is a seafaring nation with a well-developed fishing industry and this is reflected in the amount of fish and seafood eaten. The country has Europe's highest fish consumption per capita and is among the top four in the world for this indicator.[21] Fish is served grilled, boiled (including poached and simmered), fried or deep-fried, stewed (often in clay pot cooking), roasted or steamed. Foremost amongst these is bacalhau (cod), which is the type of fish most consumed in Portugal.[22] It is said that there are more than 365 ways to cook cod, one for every day of the year. Cod is almost always used dried and salted, because the Portuguese fishing tradition in the North Atlantic developed before the invention of refrigeration—therefore it needs to be soaked in water or sometimes milk before cooking. The simpler fish dishes are often flavoured with virgin olive oil, parsley, freshly squeezed lemon or lime, piri-piri sauce and white wine vinegar that can be added to your preference.

Portugal has been fishing and trading cod since the 15th century, and this cod trade accounts for its widespread use in the cuisine. Other popular seafoods include fresh sardines (especially as sardinhas assadas), brill, John Dory, sole, octopus, squid, cuttlefish, crabs, shrimp and prawns, lobster, spiny lobster, and many other crustaceans, such as barnacles, hake, horse mackerel (scad), lamprey, sea bass, scabbard (especially in Madeira), and a great variety of other fish and shellfish, as well as molluscs, such as clams, mussels, oysters, periwinkles, and scallops. Caldeirada is a stew consisting of a variety of fish and shellfish with potatoes, tomatoes, bell peppers, parsley, garlic and onions, typically seasoned with pepper.

.jpg)

Sardines used to be preserved in brine for sale in rural areas. Later, sardine canneries developed all along the Portuguese coast. Ray fish is dried in the sun in Northern Portugal. Canned tuna is widely available in Continental Portugal. Tuna used to be plentiful in the waters of the Algarve. They were trapped in fixed nets when they passed the Portuguese southern coast to spawn in the Mediterranean, and again when they returned to the Atlantic. Portuguese writer Raul Brandão, in his book Os Pescadores, describes how the tuna was hooked from the raised net into the boats, and how the fishermen would amuse themselves riding the larger fish around the net. Fresh tuna, however, is usually eaten in Madeira and the Algarve where tuna steaks are an important item in local cuisine. Canned sardines or tuna, served with boiled potatoes, black-eyed peas, collard greens, hard-boiled eggs, onion, drizzled with plenty of olive oil and seasoned with black pepper and paprika constitutes a convenient meal when there is no time to prepare anything more elaborate.

Meat and poultry

Eating meat and poultry on a daily basis was historically a privilege of the upper classes. Pork and beef are the most common meats in the country. Meat was a staple at the nobleman's table during the Middle Ages. A Portuguese Renaissance chronicler, Garcia de Resende, describes how an entrée at a royal banquet was composed of a whole roasted ox garnished with a circle of chickens. A common Portuguese dish, mainly eaten in winter, is cozido à portuguesa, which somewhat parallels the French pot-au-feu or the New England boiled dinner. Its composition depends on the cook's imagination and budget. An extensive lavish cozido may include beef, pork, salt pork, several types of enchidos (such as cured chouriço, morcela e chouriço de sangue, linguiça, farinheira, etc.), pig's feet, cured ham, potatoes, carrots, turnips, cabbage and rice. This would originally have been a favourite food of the affluent farmer, which later reached the tables of the urban bourgeoisie and typical restaurants.

Tripas à moda do Porto (tripe with white beans) is said to have originated in the 14th century, when the Castilians laid siege to Lisbon and blockaded the Tagus entrance. The Portuguese chronicler Fernão Lopes dramatically recounts how starvation spread all over the city. Food prices rose astronomically, and small boys would go to the former wheat market place in search of a few grains on the ground, which they would eagerly put in their mouths when found. Old and sick people, as well as prostitutes, or in short anybody who would not be able to aid in the city's defence, were sent out to the Castilian camp, only to be returned to Lisbon by the invaders. It was at this point that the citizens of Porto decided to organize a supply fleet that managed to slip through the river blockade. Apparently, since all available meat was sent to the capital for a while, Porto residents were limited to tripe and other organs. Whatever the truth may be, since at least the 17th century, people from Porto have been known as tripeiros or tripe eaters. Another Portuguese dish with tripe is Dobrada.

The Porto region is equally known for the toasted sandwich known as a francesinha (little Frenchie).[23][24]

In Alto Alentejo (North Alentejo), there is a very typical dish made with lungs, blood and liver, of either pork or lamb. This traditional Easter dish is eaten at other times of year as well.

Many other meat dishes feature in Portuguese cuisine. In the Bairrada area, a famous dish is Leitão à Bairrada (roasted suckling pig). Nearby, another dish, chanfana (goat slowly cooked in red wine, paprika and white pepper) is claimed by two towns, Miranda do Corvo ("Capital da Chanfana")[25] and Vila Nova de Poiares ("Capital Universal da Chanfana").[26] Carne de porco à alentejana, fried pork with clams, is a popular dish with a misleading name as it originated in the Algarve, not in Alentejo. Alentejo is a vast agricultural province with only one sizeable fishing port, Sines; and in the past, shellfish would not have been available in the inland areas. On the other hand, all points in the Algarve are relatively close to the coast and pigs used to be fed with fish, so clams were added to the fried pork to disguise the fishy taste of the meat.[27]

The Portuguese steak, bife, is a slice of fried beef or pork marinated and served in a wine-based sauce with chips, rice, or salad. To add a few more calories to this dish an egg, sunny-side up, may be placed on top of the meat, in which case the dish acquires a new name, bife com ovo a cavalo (steak with an egg on horseback)[28]. This dish is sometimes referred to as bitoque, to demonstrate the idea that the meat only "touches" the grill twice, meaning that it does not grill for too long before being served, resulting in a rare to medium-rare cut of meat. Another variation of bife is bife à casa (house steak), which may resemble the bife à cavalo[29] or may feature embellishments, such as asparagus.[30]

Iscas (fried liver) were a favourite request in old Lisbon taverns. Sometimes, they were called iscas com elas, the elas referring to sautéed potatoes. Small beef or pork steaks in a roll (pregos or bifanas, respectively) are popular snacks, often served at beer halls with a large mug of beer. In modern days, however, when time and economy demand their toll, a prego or bifana, eaten at a snack bar counter, may constitute the lunch of a white collar worker. Espetada (meat on a skewer) is very popular in Madeira. Snails caracóis are another seasonal delicacy.[31]

Alheira, a slightly smoked sausage from Trás-os-Montes, served with fried potatoes and a fried egg, has an interesting story. In the late 15th century, King Manuel of Portugal ordered all resident Jews to convert to Christianity or leave the country. The King did not really want to expel the Jews, who constituted the economic and professional élite of the kingdom, but was forced to do so by outside pressures. So, when the deadline arrived, he announced that no ships were available for those who refused conversion—the vast majority—and had men, women and children dragged to churches for a forced mass baptism. Others were even baptized near the ships themselves, which gave birth to a concept popular at the time: baptizados em pé, literally meaning: "baptized while standing". Obviously, most Jews maintained their religion secretly, but tried to show an image of being good Christians. Since avoiding pork was a tell-tale practice in the eyes of the Inquisition, converts devised a type of sausage that would give the appearance of being made with pork, but really only contained heavily spiced game and chicken. Nowadays however, pork is also used in alheiras. Furthermore, there are a few kinds of unleavened bread and cakes, such as the arrufadas de Coimbra baked throughout Continental Portugal and the Azores. In the islands, meat is often repeatedly rinsed in water to clean it of any trace of blood. After chickens are killed, they may be hung upside down, so the blood may be drained, however, paradoxically, it can be used later for cabidela.

Farinheira another Portuguese smoked sausage, uses wheat flour as base ingredient. This sausage is one of the ingredients of traditional dishes like Cozido à Portuguesa. Borba, Estremoz and Portalegre farinheiras all have confirmed PGI[32] status.[33][34]

Presunto (prosciutto ham)[35] is another important item, part of the Portuguese charcutaria cured foods. It tends to be used as an aperitif or in sandwiches.

Poultry, easily raised around a peasant's home, was at first considered quality food. Turkeys were only eaten for Christmas or on special occasions, such as wedding receptions or banquets. Up until the 1930s, the farmers from the outskirts of Lisbon would come around Christmas time to bring herds of turkeys to the city streets for sale. Before being killed, a stiff dose of brandy was forced down the birds' throats to make the meat more tender and tasty, and hopefully to ensure a happy state of mind when the time would come for the use of a sharp knife. Poor people ate chicken almost only when they were sick. Nowadays, mass production in poultry farms makes these meats accessible to all classes. Thus bifes de peru, turkey steaks, have become an addition to Portuguese tables.

Vegetables and starches

Vegetables that are popular in Portuguese cookery include cabbage, carrots, tomatoes, bell peppers, cucumber, collard greens, broccoli, pumpkin and onions. There are many starchy dishes, such as feijoada, a rich red bean stew with beef and pork. Beans are extremely popular throughout Portugal, especially kidney beans, butter beans, green beans, Braganza-beans (feijão Bragançano) black-eyed peas and chickpeas. Many dishes are served with salads usually made from tomato, lettuce, shredded carrots and onion with olive oil, vinegar and black pepper. Potatoes (French fries) and rice are also common in Portuguese cuisine.[36] Soups made from a variety of vegetables and legumes (beans, peas, broad beans, lentils, chickpeas) are commonly available, one of the most popular being caldo verde, made from potato purée, thinly sliced kale, and slices of chouriço.

Fruit, nuts and berries

Before the arrival of potatoes from the New World, chestnuts were widely used as seasonal staple ingredients, until almost totally replaced. Today there is a revival of old chestnut dishes, due to it’s naturally healthy and vitamin-rich composition.[37][38]

Other seasonal fruit, nuts and berries such as:

Pears,[39]apples,[40]table grapes,[41]plums, peaches, cherries, sour cherries,[42] melons, watermelons, citrus, figs,[43] walnuts, pine nuts, almonds, hazelnuts, strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, redcurrant and more recently blueberries[44][45] are part of the Portuguese diet. These are consumed naturally or used as desserts, marmalades, compotes, jellies and liqueurs.[46][47]

Cheese

.jpg)

There are a wide variety of Portuguese cheeses, made from cow's, goat's or sheep's milk.[48] In Portugal, cheese is usually eaten on its own before or after the main dishes. The Queijo da Serra da Estrela, can be eaten soft or more matured. Serra da Estrela is handmade from fresh sheep's milk and thistle-derived rennet. Queijo São Jorge from the Azores islands is quite famous. Other well known cheeses with protected designation of origin, include Queijo de Azeitão, Queijo de Castelo Branco. The Queijo mestiço de Tolosa, is the only[49] Portuguese cheese with protected geographical indication. It is produced in Tolosa, the village with the same name. Nearby is also Queijo de Nisa, another local variation within the Portalegre District.

Alcoholic beverages

Wines

Wine (red, white and "green") is the traditional Portuguese drink, the rosé variety being popular in non-Portuguese markets and not particularly common in Portugal itself. Vinho verde, termed "green" wine, is a specific kind of wine which can be red, white or rosé, and is only produced in the northwestern (Minho province) and does not refer to the colour of the drink, but to the fact that this wine needs to be drunk "young". A "green wine" should be consumed as a new wine while a "maduro" wine usually can be consumed after a period of ageing. Green wines are usually slightly sparkling. Port wine is a fortified wine of distinct flavour produced in Douro, which is normally served with desserts. Vinho da Madeira, is a regional wine produced in Madeira, similar to sherry. From the distillation of grape wastes from wine production, this is then turned into a variety of brandies (called aguardente, literally "burning water"), which are very strong-tasting. Typical liqueurs, such as Licor Beirão and Ginjinha, are very popular alcoholic beverages in Portugal. In the south, particularly the Algarve, a distilled spirit called medronho, is made from the fruit of the strawberry tree.

Pastries and sweets

.jpg)

Portuguese sweets have had a large impact on the development of Western cuisines. Many words like marmalade, caramel, molasses and sugar have Portuguese origins.

The origin of fried churros are fried pastry fritters sprinkled with sugar, dipped in chocolate or eaten plain, sometimes for breakfast or dessert. Served with marzipan and almonds, Portuguese sponge cake called pão-de-ló is based on a 17th century recipe.

Many of the country's typical pastries were created in the Middle Ages monasteries by nuns and monks and sold as a means of supplementing their incomes. This tradition is known as Doçaria conventual (Conventual sweets) and the names of these desserts are usually related to monastic life; barriga de freira (nun's belly), papos de anjo (angel's chests), and toucinho do céu (bacon from heaven).[50]

The main ingredient for these pastries was egg yolks. Rich egg-based desserts are still common in Portugal and are often seasoned with spices, such as cinnamon and vanilla.

Most towns have a local patisserie specialty, usually egg or cream-based pastry such as leite-creme (a dessert similar to Creme-brulée, consisting of an egg custard-base topped with a layer of hard caramel, similar ), pudim flã, pastéis de Tentúgal and many other pasties.

Other very popular pastries found in most cafés, bakeries and pastry shops across the country are the Bola de Berlim, the Bolo de arroz, and the Tentúgal pastries.[51]

Rice pudding called arroz doce is very popular,[52] as is Doce de chila/Gila made from squash), wafer paper, or candied egg threads called fios de ovos.[53][54]

Influences on world cuisine

Portugal formerly had a large empire and the cuisine has been influenced in both directions. Portuguese influences are strongly evident in Brazilian cuisine, which features its own versions of Portuguese dishes, such as feijoada and caldeirada (fish stew). Other Portuguese influences can be tasted in the Chinese territory of Macau (Macanese cuisine) and in the Indian province of Goa, where Goan dishes, such as vindalho (a spicy curry), show the pairing of vinegar, chilli pepper and garlic.

The Persian orange, grown widely in southern Europe since the 11th century, was bitter. Sweet oranges were brought from India to Europe in the 15th century by Portuguese traders. Some Southeast Indo-European languages name the orange after Portugal, which was formerly its main source of imports. Examples are Albanian portokall, Bulgarian portokal [портокал], Greek portokali [πορτοκάλι], Persian porteghal [پرتقال], and Romanian portocală. In South Italian dialects (Neapolitan), the orange is named portogallo or purtualle, literally "the Portuguese ones". Related names can also be found in other languages: Turkish Portakal, Arabic al-burtuqal [البرتقال], Amharic birtukan [ቢርቱካን], and Georgian phortokhali [ფორთოხალი].

From the sixteenth century onwards, the Portuguese started importing spices such as cinnamon, now liberally used in its traditional desserts and savoury dishes, originally from Asia.[55] Furthermore, the Portuguese "canja", a chicken soup made with rice, is a popular food therapy for the sick, which shares similarities with the Asian congee, used in the same way, suggesting it may have come from India or somewhere in the East.[56]

In 1543, Portuguese trade ships reached Japan and introduced refined sugar, valued there as a luxury good. Japanese lords enjoyed Portuguese confectionery so much it was remodelled in the now traditional Japanese konpeitō (confeito, candy), kasutera (sponge cake), and keiran somen (the Japanese version of Portuguese "fios de ovos"; this dish is also popular in Thai cuisine under the name "kanom foy tong"),[57] creating the Nanban-gashi, or "New-Style Wagashi". During this Nanban trade period, tempura was introduced to Japan by early Portuguese missionaries.

Tea was made fashionable in Britain in the 1660s after the marriage of King Charles II to the Portuguese princess Catherine of Braganza, who brought her liking for tea, originally from the colony of Macau, to the court.

All over the world, Portuguese immigrants influenced the cuisine of their new "homelands", such as Hawaii and parts of New England. Pão doce (Portuguese sweet bread), malasadas, sopa de feijão (bean soup), and Portuguese sausages (such as linguiça and chouriço) are eaten regularly in the Hawaiian islands by families of all ethnicities. Similarly, the "papo seco" is a Portuguese bread roll with an open texture, which has become a staple of cafés in Jersey, where there is a substantial Portuguese community.

In Australia, Canada and South Africa variants of "Portuguese-style" chicken, sold principally in fast food outlets, have become extremely popular in the last two decades.[58][59][60] Offerings include conventional chicken dishes and a variety of chicken and beef burgers. In some cases, such as "Portuguese chicken sandwiches", the dishes offered bear only a loose connection to Portuguese cuisine, usually only the use of "Piri-piri sauce" (a Portuguese sauce made with piri piri, which are small, fiery chili peppers), and the connection is made simply as a marketing technique.

The Portuguese had a major influence on African cuisine and vice versa. They are responsible for introducing corn in the African continent. In turn, the South African restaurant chain Nando's, among others, have helped diffusing Portuguese cuisine worldwide, in Asia for example, where the East Timorese cuisine also received influence.[61]

Madeira wine and early American history

The 18th century was the "golden age" for Madeira.[62] The wine's popularity extended from the American colonies and Brazil in the New World to Great Britain, Russia, and Northern Africa. The American colonies, in particular, were enthusiastic customers, consuming as much as a quarter of all wine produced on the island each year.

Madeira was an important wine in the history of the United States of America.[63] No wine-quality grapes could be grown among the 13 colonies,[64] so imports were needed, with a great focus on Madeira. One of the major events on the road to revolution in which Madeira played a key role was the British seizure of John Hancock's sloop the Liberty on May 9, 1768. Hancock's boat was seized after he had unloaded a cargo of 25 casks (3,150 gallons) of Madeira wine, and a dispute arose over import duties. The seizure of the Liberty caused riots to erupt among the people of Boston.[65]

Madeira wine was a favorite of Thomas Jefferson,[66][67] and it was used to toast the Declaration of Independence. George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams are also said to have appreciated the qualities of Madeira.[68] The wine was mentioned in Benjamin Franklin's autobiography. On one occasion, Adams wrote to his wife, Abigail, of the great quantities of Madeira he consumed while a Massachusetts delegate to the Continental Congress. A bottle of Madeira was used by visiting Captain James Server to christen the USS Constitution in 1797. Chief Justice John Marshall was also known to appreciate Madeira, as did his fellow justices on the early U.S. Supreme Court.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cuisine of Portugal. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Desserts of Portugal. |

References

- https://www.academia.edu/37913572/_Uma_Cozinha_Portuguesa_com_certeza_A_Culinária_Portuguesa_de_António_Maria_de_Oliveira_Bello_in_Revista_Trilhas_da_História_Vol.8_n.o15_Três_Lagoas_2018_pp._221-236

- https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=6VwGAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA242&lpg=PA242&dq=is+portuguese+cuisine+celtic&source=bl&ots=mYXtx9Qgn8&sig=ACfU3U3N54Q7pHRfLlILBQ6jUf_9VNuLJQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjyl9-oj4fqAhUJUBUIHXOsDoEQ6AEwFHoECBwQAQ#v=onepage&q=is%20portuguese%20cuisine%20celtic&f=false

- http://www.aaronokada.com/foodanddrink/portugals-past-can-be-seen-in-its-cuisine/

- https://www.academia.edu/37913572/_Uma_Cozinha_Portuguesa_com_certeza_A_Culinária_Portuguesa_de_António_Maria_de_Oliveira_Bello_in_Revista_Trilhas_da_História_Vol.8_n.o15_Três_Lagoas_2018_pp._221-236

- http://host.fieramilano.it/en/why-portuguese-influence-next-food-trend-europe

- Verbete "broa" no dicionario Priberam (in Portuguese).

- https://www.farodevigo.es/opinion/2014/04/21/broa/1008551.html

- https://tradicional.dgadr.gov.pt/pt/cat/pao-e-produtos-de-panificacao?start=12

- https://www.academia.edu/37913572/_Uma_Cozinha_Portuguesa_com_certeza_A_Culinária_Portuguesa_de_António_Maria_de_Oliveira_Bello_in_Revista_Trilhas_da_História_Vol.8_n.o15_Três_Lagoas_2018_pp._221-236

- https://www.momondo.pt/discover/culinaria-portuguesa

- https://leitesculinaria.com/7580/recipes-portuguese-kale-soup-caldo-verde.html

- https://quercusedibles.co.uk/products/portuguese-walking-stick-kale-couve-galega

- https://lusojornal.com/na-cozinha-do-vitor-caldo-verde/

- https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=uL62DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT40&lpg=PT40&dq=bacalhau+etimologia&source=bl&ots=uDN4SUaXEo&sig=ACfU3U1Lt1m_ymNFWxXTEc1a8316yFqSYw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiM_9zb-_zpAhX6VBUIHYYRAeUQ6AEwB3oECBQQAQ#v=onepage&q=bacalhau%20etimologia&f=false

- https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=YqvcBFColi8C&pg=PT159&lpg=PT159&dq=bacalhau+365+dias+ao+ano&source=bl&ots=g-9Oulkc9s&sig=ACfU3U2rtGXgC0Jjf94XF9WjF-qVLAtd8A&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjUwq2F9_zpAhVSuXEKHUTkDuYQ6AEwCnoECBMQAQ#v=onepage&q=bacalhau%20365%20dias%20ao%20ano&f=false

- https://tradicional.dgadr.gov.pt/pt/cat/queijos-e-produtos-lacteos/92-queijo-rabacal-dop

- Queijos portugueses. Infopédia [Online]. Porto: Porto Editora, 2003-2013.

- https://pastel-de-nata.pt/historia-do-pastel-de-nata/

- https://thegreatbritishbakeoff.co.uk/recipes/all/paul-hollywood-pasteis-de-nata/

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2019-04-15/portuguese-pastry-pastel-de-nata-takes-over-the-world

- (in Portuguese) PESSOA, M.F.; MENDES, B.; OLIVEIRA, J.S. CULTURAS MARINHAS EM PORTUGAL Archived 2008-10-29 at the Wayback Machine, "O consumo médio anual em produtos do mar pela população portuguesa, estima-se em cerca de 58,5 kg/ por habitante sendo, por isso, o maior consumidor em produtos marinhos da Europa e um dos quatro países a nível mundial com uma dieta à base de produtos do mar."

- SILVA, A. J. M. (2015), The fable of the cod and the promised sea. About portuguese traditions of bacalhau, in BARATA, F. T- and ROCHA, J. M. (eds.), Heritages and Memories from the Sea, Proceedings of the 1st International Conference of the UNESCO Chair in Intangible Heritage and Traditional Know-How: Linking Heritage, 14–16 January 2015. University of Evora, Évora, pp. 130-143. PDF version

- http://www.dn.pt/inicio/portugal/interior.aspx?content_id=1715506&page=-1

- http://www.telesfernandes.net/uploads/1/0/9/6/10963838/the_slow_cultural_cooking_of_francesinha.pdf

- Administrator. "Mas afinal...o que é a Chanfana?". www.bikeonelas.com.

- "Vila Nova de Poiares: Capital Universal da Chanfana".

- https://www.clubevinhosportugueses.pt/turismo/historia-e-origem-da-carne-de-porco-a-alentejana/

- https://www.196flavors.com/portugal-bitoque/

- "Bife a Casa (Portuguese House Steak)". Kidbite Lunches. 16 October 2012.

- "Gloria's Restaurant Menu". Gloria's Portuguese Restaurant.

- https://theculturetrip.com/europe/portugal/articles/a-brief-introduction-to-lisbons-favorite-summertime-snack-snails/

- https://europa.eu/youreurope/business/running-business/intellectual-property/geographical-indications/index_en.htm

- https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/quality/door/registeredName.html?denominationId=305

- https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/quality/door/registeredName.html?denominationId=306

- https://dicionario.priberam.org/presunto

- https://ncultura.pt/12-pratos-tipicos-da-gastronomia-portuguesa/

- https://digitalis-dsp.uc.pt/bitstream/10316.2/45246/1/Um%20doce%20e%20nutritivo%20fruto%20a%20castanha%20na%20historia%20da%20alimentacao.pdf

- https://tradicional.dgadr.gov.pt/pt/cat/frutos-secos-secados-e-similares/910-castanha-dos-soutos-da-lapa-dop

- http://www.iniav.pt/fotos/editor2/as_variedades_regionais_de_pereiras.pdf

- https://www.vidarural.pt/insights/recuperar-as-variedades-tradicionais-fruta-portuguesa/

- http://www.adrepes.pt/sites/default/files/publicacoes/cnvv_2017.pdf

- https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/quality/door/appliedName.html?denominationId=9251

- https://tradicional.dgadr.gov.pt/pt/cat/frutos-secos-secados-e-similares/302-figo-seco-de-torres-novas

- http://www.agronegocios.eu/noticias/desde-2012-a-producao-de-mirtilos-cresceu-700-em-portugal/

- http://www.agrotec.pt/noticias/portugal-destaca-se-pela-qualidade-do-mirtilo/

- https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=H6oQBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA58&lpg=PA58&dq=pinhoes+na+docaria+portuguesa&source=bl&ots=unSruyGdCH&sig=ACfU3U32Gw1Fx7sTc2a_wlpqnX4UF_IuYQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwicwP7JionqAhVARBUIHf2gCVcQ6AEwGXoECBIQAQ#v=onepage&q=pinhoes%20na%20docaria%20portuguesa&f=false

- https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IUPQCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA164&lpg=PA164&dq=receitas+com+frutos+e+caldas+portugal&source=bl&ots=GXgAM4Iyjz&sig=ACfU3U0Ez7Aeo1wJ5Lj_LHChketucG_c6w&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjzz-P1i4nqAhW1ShUIHdRtDAgQ6AEwG3oECBUQAQ#v=onepage&q=receitas%20com%20frutos%20e%20caldas%20portugal&f=false

- https://ncultura.pt/os-melhores-queijos-de-portugal/

- Registed cheeses from Portugal in the DOOR database of the European Union. Retrieved 26 March 2014

- https://www.academia.edu/28895914/Receitas_e_sabores_dos_territórios_rurais

- "The Prettiest Pastries of Portugal, and How to Recognize Them". Vogue. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- https://boacamaboamesa.expresso.pt/boa-mesa/2014-05-19-tradicoes-gastronomicas-o-versatil-arroz-doce

- https://tradicional.dgadr.gov.pt/pt/cat/doces-e-produtos-de-pastelaria/252-doce-de-gila

- http://www.docesregionais.com/tag/fios-de-ovos/

- https://www.suapesquisa.com/o_que_e/especiarias.htm

- http://www.icm.gov.mo/rc/viewer/30037/2035

- Kyoto Foodie, Wagashi: Angel Hair Keiran Somen (Fios de Ovos) Where and what to eat in Kyoto, 20 December 2008

- Bird on the wing Sydney Morning Herald, 16 April 2004

- https://seattle.eater.com/2019/6/26/18759816/galos-portuguese-flame-grilled-chicken-chain-canada-seattle-open

- https://www.thestar.com/entertainment/2010/11/12/torontos_best_portuguese_chicken.html

- https://www.internationalcuisine.com/about-food-and-culture-of-east-timor/

- https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=B_g5BAAAQBAJ&pg=PA156&dq=golden+age+for+madeira+wine+18th+century+america&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjG2Zel4pLqAhVMQEEAHW9hB4oQ6AEwB3oECA0QAg#v=onepage&q=golden%20age%20for%20madeira%20wine%2018th%20century%20america&f=false

- https://www.academia.edu/19747048/_Have_Some_Madeira_MDear_The_Unique_History_of_Madeira_Wine_and_Its_Consumption_in_the_Atlantic_World

- https://doi.org/10.1080/14664650500314513

- https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=Lf1aDwAAQBAJ&pg=PR2&dq=golden+age+for+madeira+wine+18th+century+america&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjG2Zel4pLqAhVMQEEAHW9hB4oQ6AEwAHoECAYQAg#v=onepage&q=golden%20age%20for%20madeira%20wine%2018th%20century%20america&f=false

- https://smithsonianassociates.org/ticketing/tickets/thomas-jefferson-and-madeira-history-and-tasting

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/lanabortolot/2019/02/18/how-to-drink-like-a-president/#6733dec13693

- https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=tTAqDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT201&lpg=PT201&dq=George+Washington,+Alexander+Hamilton,+Benjamin+Franklin,+John+Adams+Mdeira+wine&source=bl&ots=3a9CEL3ZvX&sig=ACfU3U1wqTaYnd4PHO-ByWvtvC3GgU7pZg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiQsdvX4JLqAhXUilwKHbfZA5EQ6AEwAHoECBMQAQ#v=onepage&q=George%20Washington%2C%20Alexander%20Hamilton%2C%20Benjamin%20Franklin%2C%20John%20Adams%20Mdeira%20wine&f=false

http://heloraalmeida.com.br/gastronomia/cozinha-da-senzala/

https://www.portalsaofrancisco.com.br/culinaria/culinaria-afro-brasileira

Further reading

- SILVA, A. J. M. (2015), The fable of the cod and the promised sea. About Portuguese traditions of bacalhau, in BARATA, F. T- and ROCHA, J. M. (eds.), Heritages and Memories from the Sea, Proceedings of the 1st International Conference of the UNESCO Chair in Intangible Heritage and Traditional Know-How: Linking Heritage, 14–16 January 2015. University of Evora, Évora, pp. 130–143. PDF version

- Pamela Goyan Kittler, Kathryn Sucher, Marcia Nelms (6th edition), Food and fun

.jpg)

.png)