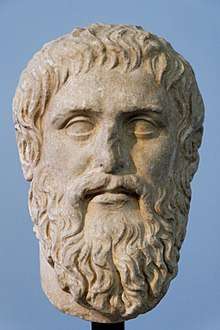

Plato's theory of soul

Plato's theory of soul, drawing on the words of his teacher Socrates, considered the psyche (ψυχή) to be the essence of a person, being that which decides how people behave. He considered this essence to be an incorporeal, eternal occupant of our being. Plato said that even after death, the soul exists and is able to think. He believed that as bodies die, the soul is continually reborn (metempsychosis) in subsequent bodies. The Platonic soul consists of three parts which are located in different regions of the body:[1][2][3]

- the logos (λογιστικόν), or logistikon, located in the head, is related to reason and regulates the other part.

- the thymos (θυμοειδές), or thumetikon, located near the chest region and is related to anger.

- the eros (ἐπιθυμητικόν), or epithumetikon, located in the stomach and is related to one's desires.

| Part of a series on |

| Platonism |

|---|

|

| Allegories and metaphors |

| Related articles |

| Related categories |

|

► Plato |

|

In his treatise the Republic, and also with the chariot allegory in Phaedrus, Plato asserted that the three parts of the psyche also correspond to the three classes of a society.[4] Whether in a city or an individual, δικαιοσύνη (dikaiosyne, justice) is declared to be the state of the whole in which each part fulfills its function, while temperance is the state of the whole where each part does not attempt to interfere in the functions of the others.[5] The function of the epithymetikon is to produce and seek pleasure. The function of the logistikon is to gently rule through the love of learning. The function of the thymoeides is to obey the directions of the logistikon while ferociously defending the whole from external invasion and internal disorder. Whether in a city or an individual, ἀδικία (adikia, injustice) is the contrary state of the whole, often taking the specific form in which the spirited listens instead to the appetitive, while they together either ignore the logical entirely or employ it in their pursuits of pleasure.

In the Republic

In Book IV of the Republic, Socrates and his interlocutors (Glaucon and Adeimantus) are attempting to answer whether the soul is one or made of parts. Socrates states that, "It is clear that the same thing will never do or undergo opposite things in the same part of it and towards the same thing at the same time; so if we find this happening, we shall know it was not one thing but more than one."[6] (This is an example of Plato's Principle of Non-Contradiction.) For instance, it seems that, given each person has only one soul, it should be impossible for a person to simultaneously desire something yet also at that very moment be averse to the same thing, as when one is tempted to commit a crime but also averse to it.[7] Both Socrates and Glaucon agree that it should not be possible for the soul to at the same time both be in one state and its opposite. From this it follows that there must be at least two aspects to soul.[8]

Reason (λογιστικόν)

The logical or logistikon (from logos) is the thinking part of the soul which loves the truth and seeks to learn it. Plato originally identifies the soul dominated by this part with the Athenian temperament.[9]

Plato makes the point that the logistikon would be the smallest part of the soul (as the rulers would be the smallest population within the Republic), but that, nevertheless, a soul can be declared just only if all three parts agree that the logistikon should rule.[10]

Spirit (θυμοειδές)

According to Plato, the spirited or thymoeides (from thymos) is the part of the soul by which we are angry or get into a temper.[11] He also calls this part 'high spirit' and initially identifies the soul dominated by this part with the Thracians, Scythians and the people of 'northern regions.'[12]

Appetite (ἐπιθυμητικόν)

The appetite or epithymetikon (from epithymia, translated to Latin as concupiscentiae or desideria)[13]

See also

- Tripartite (theology)

- Sigmund Freud's concepts of the id, ego and superego

References

- Jones, David (2009). The Gift of Logos: Essays in Continental Philosophy. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 33–35. ISBN 978-1-4438-1825-4. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- Hommel, Bernhard (2019-10-01). "Affect and control: A conceptual clarification". International Journal of Psychophysiology. 144: 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2019.07.006. ISSN 0167-8760.

- Long, A. A. Psychological Ideas in Antiquity. In: Dictionary of the History of Ideas. 1973-74 [2003]. link.

- "Plato's Ethics and Politics in The Republic" at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Retrieved August 29, 2009

- Plato Republic IV (433a)

- Republic IV: 436 b6–C1 (W. H. D. Rouse translation)

- Calian, Florian (2012). Plato’s psychology of action and the origin of agency. L'Harmattan. pp. 9–22. ISBN 978-963-236-587-9.

- Plato’s Psychology of Action and the Origin of Agency; "Ancient Theories of Soul" at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Republic IV 435 e8–9

- Republic IV 442 a

- Republic IV 439 e3–4

- Republic IV 435 e4–8

- Dixon, T. 2003. From Passions to Emotions: The Creation of a Secular Psychological Category. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 39. link.

External links

| Look up tripartite soul in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |