Bacteriophage

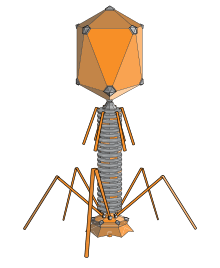

A bacteriophage (/bækˈtɪərioʊfeɪdʒ/), also known informally as a phage (/feɪdʒ/), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν (phagein), meaning "to devour". Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structures that are either simple or elaborate. Their genomes may encode as few as four genes (e.g. MS2) and as many as hundreds of genes. Phages replicate within the bacterium following the injection of their genome into its cytoplasm.

Bacteriophages are among the most common and diverse entities in the biosphere.[1] Bacteriophages are ubiquitous viruses, found wherever bacteria exist. It is estimated there are more than 1031 bacteriophages on the planet, more than every other organism on Earth, including bacteria, combined.[2] One of the densest natural sources for phages and other viruses is seawater, where up to 9x108 virions per millilitre have been found in microbial mats at the surface,[3] and up to 70% of marine bacteria may be infected by phages.[4]

Phages have been used since the late 20th century as an alternative to antibiotics in the former Soviet Union and Central Europe, as well as in France.[5][6] They are seen as a possible therapy against multi-drug-resistant strains of many bacteria (see phage therapy).[7] On the other hand, phages of Inoviridae have been shown to complicate biofilms involved in pneumonia and cystic fibrosis and to shelter the bacteria from drugs meant to eradicate disease, thus promoting persistent infection.[8]

Classification

Bacteriophages occur abundantly in the biosphere, with different genomes, and lifestyles. Phages are classified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) according to morphology and nucleic acid.

| Order | Family | Morphology | Nucleic acid | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belfryvirales | Turriviridae | Enveloped, isometric | Linear dsDNA | |

| Caudovirales | Ackermannviridae | Nonenveloped, contractile tail | Linear dsDNA | |

| Myoviridae | Nonenveloped, contractile tail | Linear dsDNA | T4, Mu, P1, P2 | |

| Siphoviridae | Nonenveloped, noncontractile tail (long) | Linear dsDNA | λ, T5, HK97, N15 | |

| Podoviridae | Nonenveloped, noncontractile tail (short) | Linear dsDNA | T7, T3, Φ29, P22 | |

| Halopanivirales | Sphaerolipoviridae | Enveloped, isometric | Linear dsDNA | |

| Haloruvirales | Pleolipoviridae | Enveloped, pleomorphic | Circular ssDNA, circular dsDNA, or linear dsDNA | |

| Kalamavirales | Tectiviridae | Nonenveloped, isometric | Linear dsDNA | |

| Levivirales | Leviviridae | Nonenveloped, isometric | Linear ssRNA | MS2, Qβ |

| Ligamenvirales | Lipothrixviridae | Enveloped, rod-shaped | Linear dsDNA | Acidianus filamentous virus 1 |

| Rudiviridae | Nonenveloped, rod-shaped | Linear dsDNA | Sulfolobus islandicus rod-shaped virus 1 | |

| Mindivirales | Cystoviridae | Enveloped, spherical | Segmented dsRNA | |

| Petitvirales | Microviridae | Nonenveloped, isometric | Circular ssDNA | ΦX174 |

| Tubulavirales | Inoviridae | Nonenveloped, filamentous | Circular ssDNA | M13 |

| Vinavirales | Corticoviridae | Nonenveloped, isometric | Circular dsDNA | PM2 |

| Unassigned | Ampullaviridae | Enveloped, bottle-shaped | Linear dsDNA | |

| Bicaudaviridae | Nonenveloped, lemon-shaped | Circular dsDNA | ||

| Clavaviridae | Nonenveloped, rod-shaped | Circular dsDNA | ||

| Finnlakeviridae | dsDNA | FLiP[9] | ||

| Fuselloviridae | Nonenveloped, lemon-shaped | Circular dsDNA | ||

| Globuloviridae | Enveloped, isometric | Linear dsDNA | ||

| Guttaviridae | Nonenveloped, ovoid | Circular dsDNA | ||

| Plasmaviridae | Enveloped, pleomorphic | Circular dsDNA | ||

| Portogloboviridae | Enveloped, isometric | Circular dsDNA | ||

| Spiraviridae | Nonnveloped, rod-shaped | Circular ssDNA | ||

| Tristromaviridae | Enveloped, rod-shaped | Linear dsDNA |

It has been suggested that members of Picobirnaviridae infect bacteria, but not mammals.[10]

Another proposed family is "Autolykiviridae" (dsDNA).[11]

History

In 1896, Ernest Hanbury Hankin reported that something in the waters of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers in India had a marked antibacterial action against cholera and it could pass through a very fine porcelain filter.[12] In 1915, British bacteriologist Frederick Twort, superintendent of the Brown Institution of London, discovered a small agent that infected and killed bacteria. He believed the agent must be one of the following:

- a stage in the life cycle of the bacteria

- an enzyme produced by the bacteria themselves, or

- a virus that grew on and destroyed the bacteria[13]

Twort's research was interrupted by the onset of World War I, as well as a shortage of funding and the discoveries of antibiotics.

Independently, French-Canadian microbiologist Félix d'Hérelle, working at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, announced on 3 September 1917, that he had discovered "an invisible, antagonistic microbe of the dysentery bacillus". For d’Hérelle, there was no question as to the nature of his discovery: "In a flash I had understood: what caused my clear spots was in fact an invisible microbe … a virus parasitic on bacteria."[14] D'Hérelle called the virus a bacteriophage, a bacteria-eater (from the Greek phagein meaning "to devour"). He also recorded a dramatic account of a man suffering from dysentery who was restored to good health by the bacteriophages.[15] It was D'Herelle who conducted much research into bacteriophages and introduced the concept of phage therapy.[16]

More than a half a century later, in 1969, Max Delbrück, Alfred Hershey, and Salvador Luria were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discoveries of the replication of viruses and their genetic structure.[17]

Uses

Phage therapy

Phages were discovered to be antibacterial agents and were used in the former Soviet Republic of Georgia (pioneered there by Giorgi Eliava with help from the co-discoverer of bacteriophages, Félix d'Herelle) during the 1920s and 1930s for treating bacterial infections. They had widespread use, including treatment of soldiers in the Red Army. However, they were abandoned for general use in the West for several reasons:

- Antibiotics were discovered and marketed widely. They were easier to make, store, and to prescribe.

- Medical trials of phages were carried out, but a basic lack of understanding raised questions about the validity of these trials.[18]

- Publication of research in the Soviet Union was mainly in the Russian or Georgian languages and for many years, was not followed internationally.

The use of phages has continued since the end of the Cold War in Russia,[19] Georgia and elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe. The first regulated, randomized, double-blind clinical trial was reported in the Journal of Wound Care in June 2009, which evaluated the safety and efficacy of a bacteriophage cocktail to treat infected venous ulcers of the leg in human patients.[20] The FDA approved the study as a Phase I clinical trial. The study's results demonstrated the safety of therapeutic application of bacteriophages, but did not show efficacy. The authors explained that the use of certain chemicals that are part of standard wound care (e.g. lactoferrin or silver) may have interfered with bacteriophage viability.[20] Shortly after that, another controlled clinical trial in Western Europe (treatment of ear infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa) was reported in the journal Clinical Otolaryngology in August 2009.[21] The study concludes that bacteriophage preparations were safe and effective for treatment of chronic ear infections in humans. Additionally, there have been numerous animal and other experimental clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of bacteriophages for various diseases, such as infected burns and wounds, and cystic fibrosis associated lung infections, among others.[21]

Meanwhile, bacteriophage researchers have been developing engineered viruses to overcome antibiotic resistance, and engineering the phage genes responsible for coding enzymes that degrade the biofilm matrix, phage structural proteins, and the enzymes responsible for lysis of the bacterial cell wall.[3][4][5] There have been results showing that T4 phages that are small in size and short-tailed, can be helpful in detecting E.coli in the human body.[22]

Therapeutic efficacy of a phage cocktail was evaluated in a mice model with nasal infection of multidrug-resistant (MDR) A. baumannii. Mice treated with the phage cocktail showed a 2.3-fold higher survival rate than those untreated in seven days post infection.[23] In 2017 a patient with a pancreas compromised by MDR A. baumannii was put on several antibiotics, despite this the patient's health continued to deteriorate during a four-month period. Without effective antibiotics the patient was subjected to phage therapy using a phage cocktail containing nine different phages that had been demonstrated to be effective against MDR A. baumannii. Once on this therapy the patient's downward clinical trajectory reversed, and returned to health.[24]

D'Herelle "quickly learned that bacteriophages are found wherever bacteria thrive: in sewers, in rivers that catch waste runoff from pipes, and in the stools of convalescent patients."[25] This includes rivers traditionally thought to have healing powers, including India's Ganges River.[26]

Other

Food industry – Since 2006, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) have approved several bacteriophage products. LMP-102 (Intralytix) was approved for treating ready-to-eat (RTE) poultry and meat products. In that same year, the FDA approved LISTEX (developed and produced by Micreos) using bacteriophages on cheese to kill Listeria monocytogenes bacteria, in order to give them generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status.[27] In July 2007, the same bacteriophage were approved for use on all food products.[28] In 2011 USDA confirmed that LISTEX is a clean label processing aid and is included in USDA.[29] Research in the field of food safety is continuing to see if lytic phages are a viable option to control other food-borne pathogens in various food products.

Dairy industry – Bacteriophages present in the environment can cause fermentation failures of cheese starter cultures. In order to avoid this, mixed-strain starter cultures and culture rotation regimes can be used.[30]

Diagnostics – In 2011, the FDA cleared the first bacteriophage-based product for in vitro diagnostic use.[31] The KeyPath MRSA/MSSA Blood Culture Test uses a cocktail of bacteriophage to detect Staphylococcus aureus in positive blood cultures and determine methicillin resistance or susceptibility. The test returns results in about five hours, compared to two to three days for standard microbial identification and susceptibility test methods. It was the first accelerated antibiotic-susceptibility test approved by the FDA.[32]

Counteracting bioweapons and toxins – Government agencies in the West have for several years been looking to Georgia and the former Soviet Union for help with exploiting phages for counteracting bioweapons and toxins, such as anthrax and botulism.[33] Developments are continuing among research groups in the U.S. Other uses include spray application in horticulture for protecting plants and vegetable produce from decay and the spread of bacterial disease. Other applications for bacteriophages are as biocides for environmental surfaces, e.g., in hospitals, and as preventative treatments for catheters and medical devices before use in clinical settings. The technology for phages to be applied to dry surfaces, e.g., uniforms, curtains, or even sutures for surgery now exists. Clinical trials reported in Clinical Otolaryngology[21] show success in veterinary treatment of pet dogs with otitis.

The SEPTIC bacterium sensing and identification method uses the ion emission and its dynamics during phage infection and offers high specificity and speed for detection.[34]

Phage display is a different use of phages involving a library of phages with a variable peptide linked to a surface protein. Each phage genome encodes the variant of the protein displayed on its surface (hence the name), providing a link between the peptide variant and its encoding gene. Variant phages from the library may be selected through their binding affinity to an immobilized molecule (e.g., botulism toxin) to neutralize it. The bound, selected phages can be multiplied by reinfecting a susceptible bacterial strain, thus allowing them to retrieve the peptides encoded in them for further study.[35]

Antimicrobial drug discovery – Phage proteins often have antimicrobial activity and may serve as leads for peptidomimetics, i.e. drugs that mimic peptides.[36] Phage-ligand technology makes use of phage proteins for various applications, such as binding of bacteria and bacterial components (e.g. endotoxin) and lysis of bacteria.[37]

Basic research – Bacteriophages are important model organisms for studying principles of evolution and ecology.[38]

Replication

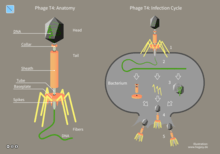

Bacteriophages may have a lytic cycle or a lysogenic cycle. With lytic phages such as the T4 phage, bacterial cells are broken open (lysed) and destroyed after immediate replication of the virion. As soon as the cell is destroyed, the phage progeny can find new hosts to infect. Lytic phages are more suitable for phage therapy. Some lytic phages undergo a phenomenon known as lysis inhibition, where completed phage progeny will not immediately lyse out of the cell if extracellular phage concentrations are high. This mechanism is not identical to that of temperate phage going dormant and usually, is temporary.

In contrast, the lysogenic cycle does not result in immediate lysing of the host cell. Those phages able to undergo lysogeny are known as temperate phages. Their viral genome will integrate with host DNA and replicate along with it, relatively harmlessly, or may even become established as a plasmid. The virus remains dormant until host conditions deteriorate, perhaps due to depletion of nutrients, then, the endogenous phages (known as prophages) become active. At this point they initiate the reproductive cycle, resulting in lysis of the host cell. As the lysogenic cycle allows the host cell to continue to survive and reproduce, the virus is replicated in all offspring of the cell. An example of a bacteriophage known to follow the lysogenic cycle and the lytic cycle is the phage lambda of E. coli.[39]

Sometimes prophages may provide benefits to the host bacterium while they are dormant by adding new functions to the bacterial genome, in a phenomenon called lysogenic conversion. Examples are the conversion of harmless strains of Corynebacterium diphtheriae or Vibrio cholerae by bacteriophages, to highly virulent ones that cause diphtheria or cholera, respectively.[40][41] Strategies to combat certain bacterial infections by targeting these toxin-encoding prophages have been proposed.[42]

Attachment and penetration

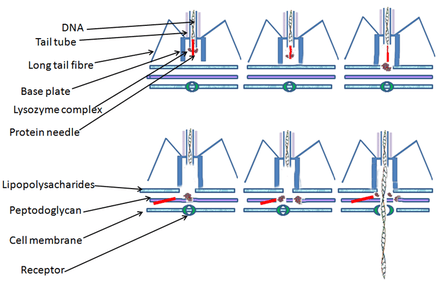

Bacterial cells are protected by a cell wall of polysaccharides, which are important virulence factors protecting bacterial cells against both immune host defenses and antibiotics.[43] To enter a host cell, bacteriophages attach to specific receptors on the surface of bacteria, including lipopolysaccharides, teichoic acids, proteins, or even flagella. This specificity means a bacteriophage can infect only certain bacteria bearing receptors to which they can bind, which in turn, determines the phage's host range. Polysaccharide-degrading enzymes, like endolysins are virion-associated proteins to enzymatically degrade the capsular outer layer of their hosts, at the initial step of a tightly programmed phage infection process. Host growth conditions also influence the ability of the phage to attach and invade them.[44] As phage virions do not move independently, they must rely on random encounters with the correct receptors when in solution, such as blood, lymphatic circulation, irrigation, soil water, etc.

Myovirus bacteriophages use a hypodermic syringe-like motion to inject their genetic material into the cell. After contacting the appropriate receptor, the tail fibers flex to bring the base plate closer to the surface of the cell. This is known as reversible binding. Once attached completely, irreversible binding is initiated and the tail contracts, possibly with the help of ATP, present in the tail,[4] injecting genetic material through the bacterial membrane.[45] The injection is accomplished through a sort of bending motion in the shaft by going to the side, contracting closer to the cell and pushing back up. Podoviruses lack an elongated tail sheath like that of a myovirus, so instead, they use their small, tooth-like tail fibers enzymatically to degrade a portion of the cell membrane before inserting their genetic material.

Synthesis of proteins and nucleic acid

Within minutes, bacterial ribosomes start translating viral mRNA into protein. For RNA-based phages, RNA replicase is synthesized early in the process. Proteins modify the bacterial RNA polymerase so it preferentially transcribes viral mRNA. The host's normal synthesis of proteins and nucleic acids is disrupted, and it is forced to manufacture viral products instead. These products go on to become part of new virions within the cell, helper proteins that contribute to the assemblage of new virions, or proteins involved in cell lysis. In 1972, Walter Fiers (University of Ghent, Belgium) was the first to establish the complete nucleotide sequence of a gene and in 1976, of the viral genome of bacteriophage MS2.[46] Some dsDNA bacteriophages encode ribosomal proteins, which are thought to modulate protein translation during phage infection.[47]

Virion assembly

In the case of the T4 phage, the construction of new virus particles involves the assistance of helper proteins. The base plates are assembled first, with the tails being built upon them afterward. The head capsids, constructed separately, will spontaneously assemble with the tails. The DNA is packed efficiently within the heads. The whole process takes about 15 minutes.

Release of virions

Phages may be released via cell lysis, by extrusion, or, in a few cases, by budding. Lysis, by tailed phages, is achieved by an enzyme called endolysin, which attacks and breaks down the cell wall peptidoglycan. An altogether different phage type, the filamentous phage, make the host cell continually secrete new virus particles. Released virions are described as free, and, unless defective, are capable of infecting a new bacterium. Budding is associated with certain Mycoplasma phages. In contrast to virion release, phages displaying a lysogenic cycle do not kill the host but, rather, become long-term residents as prophage.

Genome structure

Given the millions of different phages in the environment, phage genomes come in a variety of forms and sizes. RNA phage such as MS2 have the smallest genomes, of only a few kilobases. However, some DNA phage such as T4 may have large genomes with hundreds of genes; the size and shape of the capsid varies along with the size of the genome.[50] The largest bacteriophage genomes reach a size of 735 kb.[51]

Bacteriophage genomes can be highly mosaic, i.e. the genome of many phage species appear to be composed of numerous individual modules. These modules may be found in other phage species in different arrangements. Mycobacteriophages, bacteriophages with mycobacterial hosts, have provided excellent examples of this mosaicism. In these mycobacteriophages, genetic assortment may be the result of repeated instances of site-specific recombination and illegitimate recombination (the result of phage genome acquisition of bacterial host genetic sequences).[52] Evolutionary mechanisms shaping the genomes of bacterial viruses vary between different families and depend upon the type of the nucleic acid, characteristics of the virion structure, as well as the mode of the viral life cycle.[53]

Systems biology

Phages often have dramatic effects on their hosts. As a consequence, the transcription pattern of the infected bacterium may change considerably. For instance, infection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by the temperate phage PaP3 changed the expression of 38% (2160/5633) of its host's genes. Many of these effects are probably indirect, hence the challenge becomes to identify the direct interactions among bacteria and phage.[54]

Several attempts have been made to map protein–protein interactions among phage and their host. For instance, bacteriophage lambda was found to interact with its host, E. coli, by 31 interactions. However, a large-scale study revealed 62 interactions, most of which were new. Again, the significance of many of these interactions remains unclear, but these studies suggest that there most likely are several key interactions and many indirect interactions whose role remains uncharacterized.[55]

In the environment

Metagenomics has allowed the in-water detection of bacteriophages that was not possible previously.[56]

Also, bacteriophages have been used in hydrological tracing and modelling in river systems, especially where surface water and groundwater interactions occur. The use of phages is preferred to the more conventional dye marker because they are significantly less absorbed when passing through ground waters and they are readily detected at very low concentrations.[57] Non-polluted water may contain approximately 2×108 bacteriophages per ml.[58]

Bacteriophages are thought to contribute extensively to horizontal gene transfer in natural environments, principally via transduction, but also via transformation.[59] Metagenomics-based studies also have revealed that viromes from a variety of environments harbor antibiotic-resistance genes, including those that could confer multidrug resistance.[60]

Model bacteriophages

The following bacteriophages are extensively studied:

See also

- Virophage, viruses that infect other viruses

- Bacterivore

- CrAssphage

- DNA viruses

- Phage ecology

- Phage monographs (a comprehensive listing of phage and phage-associated monographs, 1921 – present)

- Polyphage

- RNA viruses

- Transduction

- Viriome

- CRISPR

References

- McGrath S and van Sinderen D (editors). (2007). Bacteriophage: Genetics and Molecular Biology (1st ed.). Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-14-1.

- "Novel Phage Therapy Saves Patient with Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Infection". UC Health – UC San Diego. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- Wommack, K. E.; Colwell, R. R. (2000). "Virioplankton: Viruses in Aquatic Ecosystems". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 64 (1): 69–114. doi:10.1128/MMBR.64.1.69-114.2000. PMC 98987. PMID 10704475.

- Prescott, L. (1993). Microbiology, Wm. C. Brown Publishers, ISBN 0-697-01372-3

- BBC Horizon (1997): The Virus that Cures – Documentary about the history of phage medicine in Russia and the West

- Borrell, Brendan (August 2012). "Science talk: Phage factor". Scientific American. pp. 80–83.

- Keen, E. C. (2012). "Phage Therapy: Concept to Cure". Frontiers in Microbiology. 3: 238. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00238. PMC 3400130. PMID 22833738.

- "Bacteria and bacteriophages collude in the formation of clinically frustrating biofilms".

- Elina Laanto, Sari Mäntynen, Luigi De Colibus, Jenni Marjakangas, Ashley Gillum, David I. Stuart, Janne J. Ravantti, Juha Huiskonen, Lotta-Riina Sundberg: Virus found in a boreal lake links ssDNA and dsDNA viruses. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114(31), July 2017, doi:10.1073/pnas.1703834114

- Krishnamurthy SR, Wang D (2018). "Extensive conservation of prokaryotic ribosomal binding sites in known and novel picobirnaviruses". Virology. 516: 108–114. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2018.01.006. PMID 29346073.

- Kathryn M. Kauffman, Fatima A. Hussain, Joy Yang, Philip Arevalo, Julia M. Brown, William K. Chang, David VanInsberghe, Joseph Elsherbini, Radhey S. Sharma, Michael B. Cutler, Libusha Kelly, Martin F. Polz: A major lineage of non-tailed dsDNA viruses as unrecognized killers of marine bacteria. In: Nature Vol. 554, pp. 118–122. January 24th, 2018. doi:10.1038/nature25474

- Hankin E H. (1896). "L'action bactericide des eaux de la Jumna et du Gange sur le vibrion du cholera". Annales de l'Institut Pasteur (in French). 10: 511–523.

- Twort, F. W. (1915). "An Investigation on the Nature of Ultra-Microscopic Viruses". The Lancet. 186 (4814): 1241–1243. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)20383-3.

- d'Hérelles, Félix (1917). "Sur un microbe invisible antagoniste des bacilles dysentériques" (PDF). Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris. 165: 373–5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- d'Hérelles, Félix (1949). "The bacteriophage" (PDF). Science News. 14: 44–59. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- Keen EC (2012). "Felix d'Herelle and Our Microbial Future". Future Microbiology. 7 (12): 1337–1339. doi:10.2217/fmb.12.115. PMID 23231482.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1969". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- Kutter, Elizabeth; De Vos, Daniel; Gvasalia, Guram; Alavidze, Zemphira; Gogokhia, Lasha; Kuhl, Sarah; Abedon, Stephen (1 January 2010). "Phage Therapy in Clinical Practice: Treatment of Human Infections". Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 11 (1): 69–86. doi:10.2174/138920110790725401. PMID 20214609. S2CID 31626252.

- Сергей Головин Бактериофаги: убийцы в роли спасителей // Наука и жизнь. – 2017. – № 6. – С. 26–33

- Rhoads, DD; Wolcott, RD; Kuskowski, MA; Wolcott, BM; Ward, LS; Sulakvelidze, A (June 2009). "Bacteriophage therapy of venous leg ulcers in humans: results of a phase I safety trial". Journal of Wound Care. 18 (6): 237–8, 240–3. doi:10.12968/jowc.2009.18.6.42801. PMID 19661847.

- Wright, A.; Hawkins, C.H.; Änggård, E.E.; Harper, D.R. (August 2009). "A controlled clinical trial of a therapeutic bacteriophage preparation in chronic otitis due to antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa; a preliminary report of efficacy". Clinical Otolaryngology. 34 (4): 349–357. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01973.x. PMID 19673983.

- Tawil, Nancy (April 2012). "Surface plasmon resonance detection of E. coli and mathicillin-resistant S. aureus bacteriophages". PLOS Genetics. 3 (5): e78. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030078. PMC 1877875. PMID 17530925.

- Cha, Kyoungeun; Oh, Hynu K.; Jang, Jae Y.; Jo, Yunyeol; Kim, Won K.; Ha, Geon U.; Ko, Kwan S.; Myung, Heejoon (10 April 2018). "Characterization of Two Novel Bacteriophages Infecting Multidrug-Resistant (MDR) Acinetobacter baumannii and Evaluation of Their Therapeutic Efficacy in Vivo". Frontiers in Microbiology. 9: 696. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00696. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 5932359. PMID 29755420.

- Schooley, Robert T.; Biswas, Biswajit; Gill, Jason J.; Hernandez-Morales, Adriana; Lancaster, Jacob; Lessor, Lauren; Barr, Jeremy J.; Reed, Sharon L.; Rohwer, Forest (October 2017). "Development and Use of Personalized Bacteriophage-Based Therapeutic Cocktails To Treat a Patient with a Disseminated Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infection". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 61 (10). doi:10.1128/AAC.00954-17. ISSN 0066-4804. PMC 5610518. PMID 28807909.

- Kuchment, Anna (2012), The Forgotten Cure: The past and future of phage therapy, Springer, p. 11, ISBN 978-1-4614-0250-3

- Deresinski, Stan (15 April 2009). "Bacteriophage Therapy: Exploiting Smaller Fleas" (PDF). Clinical Infectious Diseases. 48 (8): 1096–1101. doi:10.1086/597405. PMID 19275495.

- U.S. FDA/CFSAN: Agency Response Letter, GRAS Notice No. 000198

- (U.S. FDA/CFSAN: Agency Response Letter, GRAS Notice No. 000218)

- FSIS Directive 7120 Archived 18 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Atamer, Zeynep; Samtlebe, Meike; Neve, Horst; J. Heller, Knut; Hinrichs, Joerg (16 July 2013). "Review: elimination of bacteriophages in whey and whey products". Frontiers in Microbiology. 4: 191. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2013.00191. PMC 3712493. PMID 23882262.

- FDA 510(k) Premarket Notification

- FDA clears first test to quickly diagnose and distinguish MRSA and MSSA. FDA (6 May 2011)

- Vaisman, Daria (25 May 2007) Studying anthrax in a Soviet-era lab – with Western funding. The New York Times

- Dobozi-King, M.; Seo, S.; Kim, J.U.; Young, R.; Cheng, M.; Kish, L.B. (2005). "Rapid detection and identification of bacteria: SEnsing of Phage-Triggered Ion Cascade (SEPTIC)" (PDF). Journal of Biological Physics and Chemistry. 5: 3–7. doi:10.4024/1050501.jbpc.05.01.

- Smith GP, Petrenko VA (April 1997). "Phage Display". Chem. Rev. 97 (2): 391–410. doi:10.1021/cr960065d. PMID 11848876.

- Liu, Jing; Dehbi, Mohammed; Moeck, Greg; Arhin, Francis; Bauda, Pascale; Bergeron, Dominique; Callejo, Mario; Ferretti, Vincent; Ha, Nhuan (February 2004). "Antimicrobial drug discovery through bacteriophage genomics". Nature Biotechnology. 22 (2): 185–191. doi:10.1038/nbt932. PMID 14716317. S2CID 9905115.

- Technological background Phage-ligand technology

- Keen, E. C. (2014). "Tradeoffs in bacteriophage life histories". Bacteriophage. 4 (1): e28365. doi:10.4161/bact.28365. PMC 3942329. PMID 24616839.

- Mason, Kenneth A., Jonathan B. Losos, Susan R. Singer, Peter H Raven, and George B. Johnson. (2011). Biology, p. 533. McGraw-Hill, New York. ISBN 978-0-07-893649-4.

- Mokrousov I (2009). "Corynebacterium diphtheriae: genome diversity, population structure and genotyping perspectives". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 9 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2008.09.011. PMID 19007916.

- Charles RC, Ryan ET (October 2011). "Cholera in the 21st century". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 24 (5): 472–7. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834a88af. PMID 21799407.

- Keen, E. C. (December 2012). "Paradigms of pathogenesis: Targeting the mobile genetic elements of disease". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2: 161. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2012.00161. PMC 3522046. PMID 23248780.

- Drulis-Kawa, Zuzanna; Majkowska-Skrobek, Grazyna; MacIejewska, Barbara (2015). "Bacteriophages and Phage-Derived Proteins – Application Approaches". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 22 (14): 1757–1773. doi:10.2174/0929867322666150209152851. PMC 4468916. PMID 25666799.

- Gabashvili, I.; Khan, S.; Hayes, S.; Serwer, P. (1997). "Polymorphism of bacteriophage T7". Journal of Molecular Biology. 273 (3): 658–67. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1997.1353. PMID 9356254.

- Maghsoodi, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Andricioaei, I.; Perkins, N.C. (25 November 2019). "How the phage T4 injection machinery works including energetics, forces, and dynamic pathway". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (50): 25097–25105. doi:10.1073/pnas.1909298116. ISSN 0027-8424.

- Fiers, W.; Contreras, R.; Duerinck, F.; Haegeman, G.; Iserentant, D.; Merregaert, J.; Min Jou, W.; Molemans, F.; Raeymaekers, A.; Van Den Berghe, A.; Volckaert, G.; Ysebaert, M. (1976). "Complete nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage MS2 RNA: primary and secondary structure of the replicase gene". Nature. 260 (5551): 500–507. Bibcode:1976Natur.260..500F. doi:10.1038/260500a0. PMID 1264203. S2CID 4289674.

- Mizuno, CM; Guyomar, C; Roux, S; Lavigne, R; Rodriguez-Valera, F; Sullivan, MB; Gillet, R; Forterre, P; Krupovic, M (2019). "Numerous cultivated and uncultivated viruses encode ribosomal proteins". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 752. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..752M. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-08672-6. PMC 6375957. PMID 30765709.

- Callaway, Ewen (2017). "Do you speak virus? Phages caught sending chemical messages". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.21313.

- Erez, Zohar; Steinberger-Levy, Ida; Shamir, Maya; Doron, Shany; Stokar-Avihail, Avigail; Peleg, Yoav; Melamed, Sarah; Leavitt, Azita; Savidor, Alon; Albeck, Shira; Amitai, Gil; Sorek, Rotem (26 January 2017). "Communication between viruses guides lysis–lysogeny decisions". Nature. 541 (7638): 488–493. Bibcode:2017Natur.541..488E. doi:10.1038/nature21049. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 5378303. PMID 28099413.

- Black, LW; Thomas, JA (2012). Condensed genome structure. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 726. pp. 469–87. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-0980-9_21. ISBN 978-1-4614-0979-3. PMC 3559133. PMID 22297527.

- Al-Shayeb, Basem; Sachdeva, Rohan; Chen, Lin-Xing; Ward, Fred; Munk, Patrick; Devoto, Audra; Castelle, Cindy J.; Olm, Matthew R.; Bouma-Gregson, Keith; Amano, Yuki; He, Christine (February 2020). "Clades of huge phages from across Earth's ecosystems". Nature. 578 (7795): 425–431. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2007-4. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 7162821. PMID 32051592.

- Morris P, Marinelli LJ, Jacobs-Sera D, Hendrix RW, Hatfull GF (March 2008). "Genomic characterization of mycobacteriophage Giles: evidence for phage acquisition of host DNA by illegitimate recombination". Journal of Bacteriology. 190 (6): 2172–82. doi:10.1128/JB.01657-07. PMC 2258872. PMID 18178732.

- Krupovic M, Prangishvili D, Hendrix RW, Bamford DH (December 2011). "Genomics of bacterial and archaeal viruses: dynamics within the prokaryotic virosphere". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 75 (4): 610–35. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00011-11. PMC 3232739. PMID 22126996.

- Zhao X, Chen C, Shen W, Huang G, Le S, Lu S, Li M, Zhao Y, Wang J, Rao X, Li G, Shen M, Guo K, Yang Y, Tan Y, Hu F (2016). "Global Transcriptomic Analysis of Interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Bacteriophage PaP3". Sci Rep. 6: 19237. Bibcode:2016NatSR...619237Z. doi:10.1038/srep19237. PMC 4707531. PMID 26750429.

- Blasche S, Wuchty S, Rajagopala SV, Uetz P (2013). "The protein interaction network of bacteriophage lambda with its host, Escherichia coli". J. Virol. 87 (23): 12745–55. doi:10.1128/JVI.02495-13. PMC 3838138. PMID 24049175.

- Breitbart M, Salamon P, Andresen B, Mahaffy JM, Segall AM, Mead D, Azam F, Rohwer F (October 2002). "Genomic analysis of uncultured marine viral communities". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (22): 14250–5. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9914250B. doi:10.1073/pnas.202488399. PMC 137870. PMID 12384570.

- Martin, C. (1988). "The Application of Bacteriophage Tracer Techniques in South West Water". Water and Environment Journal. 2 (6): 638–642. doi:10.1111/j.1747-6593.1988.tb01352.x.

- Bergh, O (1989). "High abundance of viruses found in aquatic environments". Nature. 340 (6233): 467–468. Bibcode:1989Natur.340..467B. doi:10.1038/340467a0. PMID 2755508. S2CID 4271861.

- Keen, Eric C.; Bliskovsky, Valery V.; Malagon, Francisco; Baker, James D.; Prince, Jeffrey S.; Klaus, James S.; Adhya, Sankar L.; Groisman, Eduardo A. (2017). "Novel "Superspreader" Bacteriophages Promote Horizontal Gene Transfer by Transformation". mBio. 8 (1): e02115–16. doi:10.1128/mBio.02115-16. PMC 5241400. PMID 28096488.

- Lekunberri, Itziar; Subirats, Jessica; Borrego, Carles M.; Balcazar, Jose L. (2017). "Exploring the contribution of bacteriophages to antibiotic resistance". Environmental Pollution. 220 (Pt B): 981–984. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2016.11.059. hdl:10256/14115. PMID 27890586.

- Strauss, James H.; Sinsheimer, Robert L. (July 1963). "Purification and properties of bacteriophage MS2 and of its ribonucleic acid". Journal of Molecular Biology. 7 (1): 43–54. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(63)80017-0. PMID 13978804.

- Miller, ES; Kutter, E; Mosig, G; Arisaka, F; Kunisawa, T; Rüger, W (March 2003). "Bacteriophage T4 genome". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 67 (1): 86–156, table of contents. doi:10.1128/MMBR.67.1.86-156.2003. PMC 150520. PMID 12626685.

- Ackermann, H.-W.; Krisch, H. M. (6 April 2014). "A catalogue of T4-type bacteriophages". Archives of Virology. 142 (12): 2329–2345. doi:10.1007/s007050050246. PMID 9672598. S2CID 39369249.

Bibliography

- Hauser, AR (2016). "Beyond Antibiotics: New Therapeutic Approaches for Bacterial Infections". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 63 (1): 89–95. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw200. PMC 4901866. PMID 27025826.

- Strathdee, Steffanie; Patterson, Tom (2019). The Perfect Predator. Hachette Books. ISBN 978-0316418089.

External links

- Häusler, T. (2006) "Viruses vs. Superbugs", Macmillan

- Animation of bacteriophage targeting E. coli bacteria

- Phage.org general information on bacteriophages

- bacteriophages illustrations and genomics

- Bacteriophages get a foothold on their prey

- NPR Science Friday podcast, "Using 'Phage' Viruses to Help Fight Infection", April 2008

- Animation of a scientifically correct T4 bacteriophage targeting E. coli bacteria

- Animation by Hybrid Animation Medical for a T4 Bacteriophage targeting E. coli bacteria

- Bacteriophages: What are they. Presentation by Professor Graham Hatfull, University of Pittsburgh on YouTube