People's Republic of Angola

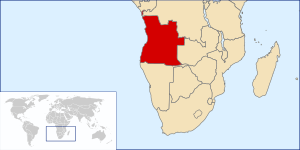

The People's Republic of Angola (Portuguese: República Popular de Angola) was the self-declared socialist state which governed Angola from its independence in 1975 until 1992, during the Angolan Civil War.

People's Republic of Angola República Popular de Angola | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975–1992 | |||||||||

.png) Coat of arms

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Luanda | ||||||||

| Common languages | Portuguese | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary Marxist-Leninist one-party socialist republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1975−1979 | Agostinho Neto | ||||||||

• 1979−1992 | José Eduardo dos Santos | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1975−1978 | Lopo do Nascimento | ||||||||

• 1991−1992 | Fernando José de França Dias Van-Dúnem | ||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||

• Independence from Portugal | 11 November 1975 | ||||||||

| 22 November 1976 | |||||||||

| 25 August 1992 | |||||||||

| Currency | Kwanza | ||||||||

| Calling code | 244 | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | AO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

History

The regime was established in 1975, after Portuguese Angola, an autonomous State[1], was granted independence from Portugal through the Alvor Agreement.[2][3] The situation in Portugal's other former large African autonomous State[1], the People's Republic of Mozambique, was similar.[4] The newly-founded nation had friendly relations with the Soviet Union, Cuba, and the People's Republic of Mozambique.[5] The country was governed by the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), which was responsible for the transition into a Marxist-Leninist one-party state. The group was backed by both Cuba and the Soviet Union.

The Angolan government managed its oil windfall effectively. The trade balance remained profitable and external debt was kept within reasonable limits. In 1985, debt service amounted to $324 million, or about 15% of exports.[6]

A major effort was made in the field of adult education and literacy, particularly in urban centres. In 1986, the number of primary school students exceeded one and a half million, and nearly half a million adults learned to read and write. The language of instruction remained mainly Portuguese, but experiments were tried to introduce the study of local African languages from the first years of schooling. Relations between the churches and the ruling party remained relatively calm.[6]

An opposing group, known as the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), led by Jonas Savimbi, sparked a civil war with the MPLA, with the backing from both apartheid South Africa and the United States,[7] establishing the Democratic People's Republic of Angola in opposition to the People's Republic of Angola. The United States did everything they could in order to prevent the spread of communism in Africa and this is the largest example.[8]

In January 1984, an agreement was negotiated. South Africa obtained from Angola a promise to withdraw its support for the SWAPO (Namibian independence movement established in Angola since 1975) in exchange for the evacuation of South African troops from Angola. Despite this agreement, South Africa, under the pretext of pursuing SWAPO guerrillas, conducted large-scale operations on Angolan soil whenever UNITA was under attack by Angolan government forces. In parallel, South Africa organised attacks in Angola. In May 1985, an Angolan patrol intercepted a South African special forces unit in Malongo that was about to sabotage oil installations.[6]

The United States provided Stinger surface-to-air missiles to rebels through the Kamina base in southern Zaire, a base that the United States considered permanently reactivating. US assistance also included anti-tank weapons to enable UNITA to better resist the Luanda Army's increasingly threatening offensives against areas still under its control in the east and south-east of the country.[6]

In the 1980s, South Africa continued to support UNITA, and the Luanda government lost hope of a military victory in the short term. In 1988, the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale, where Cuban-backed MPLA forces defeated South African air superiority, marked a decisive turning point for the region: Namibia's independence, the inexorable decline of the segregationist regime. This led the President of the African National Congress, Jacob Zuma, who was invited to the 20th anniversary celebrations of the Battle of Cuito on 23 March 2008, to say that "the contribution of the MPLA and the Angolan people to the struggle for the abolition of apartheid in South Africa is second to none in any country on the continent".[9]

In 1991, the MPLA and UNITA signed the peace agreement known as the Bicesse Accords, which allowed for multiparty elections in Angola.

In 1992, the People's Republic of Angola was constitutionally succeeded by the Republic of Angola and elections were held. However, the peace agreement did not last, as Savimbi rejected the election results and fighting resumed across the country until his death in 2002.[10]

See also

- African Socialism

References

- "Lei 5/72, 1972-06-23". Diário da República Eletrónico (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- Rothchild, Donald S. (1997). Managing Ethnic Conflict in Africa: Pressures and Incentives for Cooperation. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 1997. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-8157-7593-5.

- Tvedten, Inge (1997). Angola: Struggle for Peace and Reconstruction. London. pp. 3. ISBN 978-0-8133-3335-9.

- Faria, P.C.J. (2013). The Post-war Angola: Public Sphere, Political Regime and Democracy. EBSCO ebook academic collection. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-4438-6671-2. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- "Angola – Communist Nations". www.country-data.com.

- Fernando Andresen Guimaráes, The Origins of the Angolan Civil War : Foreign Intervention and Domestic Political Conflict, Basingstoke & Londres, Houndsmills, 1998.

- "African Socialism". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2018-09-11.

- "Angola - INDEPENDENCE AND THE RISE OF THE MPLA GOVERNMENT". countrystudies.us. Retrieved 2018-06-03.

- https://jacqver.pagesperso-orange.fr/texte/apresguerreetornoirenangola.htm

- French, Howard W. (3 March 2002). "The World; Exit Savimbi, and the Cold War in Africa". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 September 2018.