Participatory budgeting

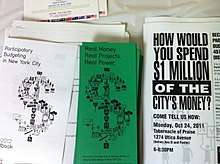

Participatory budgeting (PB) is a process of democratic deliberation and decision-making, in which ordinary people decide how to allocate part of a municipal or public budget. Participatory budgeting allows citizens to identify, discuss, and prioritize public spending projects, and gives them the power to make real decisions about how money is spent.[1]

PB processes are typically designed to involve those left out of traditional methods of public engagement, such as low-income residents, non-citizens, and youth.[2] A comprehensive case study of eight municipalities in Brazil analyzing the successes and failures of participatory budgeting has suggested that it often results in more equitable public spending, greater government transparency and accountability, increased levels of public participation (especially by marginalized or poorer residents), and democratic and citizenship learning.[3]

The frameworks of PB differentiate variously throughout the globe in terms of scale, procedure, and objective. PB, in its conception, is often contextualized to suit a region's particular conditions and needs. Thus, the magnitudes of PB vary depending on whether it is carried out at a municipal, regional, or provincial level. In many cases, PB has been legally enforced and regulated; however, some are internally arranged and promoted. Since the original invention in Porto Alegre, Brazil, in 1988, PB has manifested itself in a myriad of designs, with variations in methodology, form, and technology.[4] PB stands as one of several democratic innovations such as British Columbia's Citizens' Assembly, encompassing the ideals of a participatory democracy.[5] Today, PB has been implemented in nearly 1,500 municipalities and institutions around the world.[5]

Procedure

Most broadly, all participatory budgeting schemes allow citizens to deliberate with the goal of creating either a concrete financial plan (a budget), or a recommendation to elected representatives. In the Porto Alegre model, the structure of the scheme gives subjurisdictions (neighborhoods) authority over the larger political jurisdiction (the city) of which they are part. Neighborhood budget committees, for example, have authority to determine the citywide budget, not just the allocation of resources for their particular neighborhood. There is, therefore, a need for mediating institutions to facilitate the aggregation of budget preferences expressed by subjurisdictions.

According to the World Bank Group, certain factors are needed for PB to be adopted: "[…] strong mayoral support, a civil society willing and able to contribute to ongoing policy debates, a generally supportive political environment that insulates participatory budgeting from legislators' attacks, and financial resources to fund the projects selected by citizens."[6]:24 In addition, there are generally two approaches through which PB formulates: top-down versus bottom-up. The adoption of PB has been required by the federal government in nations such as Peru, while there are cases where local governments initiated PB independent from the national agenda such as Porto Alegre. With the bottom-up approach, NGO's and local organizations have played crucial roles in mobilizing and informing the community members.[6]:24

PB processes do not adhere to strict rules, but they generally share several basic steps:[6]:26

- The municipality is divided geographically into multiple districts.

- Representatives of the divided districts are either elected or volunteered to work with government officials in a PB committee.

- The committees are established with regularly scheduled meetings under a specific timeline to deliberate.

- Proposals, initiated by the citizens, are dealt under different branches of public budget such as recreation, infrastructure, transportation, etc.

- Participants publicly deliberate with the committee to finalize the projects to be voted on.

- The drafted budget is shared to the public and put for a vote.

- The municipal government implements the top proposals.

- The cycle is repeated on an annual basis.

A participatory budgeting algorithm is sometimes used in order to calculate the budget allocation from the votes.

History

Participatory Budgeting was first developed in the 1980s by the Brazilian Workers' Party, drawing on the party's stated belief that electoral success is not an end in itself but a spring board for developing radical, participatory forms of democracy. While there were several early experiments (including the public budgeting practices of the Brazilian Democratic Movement in municipalities such as Pelotas [6]:92), the first full participatory budgeting process was implemented in 1989, in the city of Porto Alegre, Brazil, a capital city of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, and a busy industrial, financial, and service center, at that time with a population of 1.2 million.[7] The initial success of PB in Porto Alegre soon made it attractive to other municipalities. By 2001, more than 100 cities in Brazil had implemented PB, while in 2015, thousands of variations have been implemented in the Americas, Africa, Asia and Europe.[8]

Porto Alegre

In its first Title, the 1988 Constitution of Brazil states that "All power originates from the people, who exercise it by the means of elected representatives or directly, according to the terms of this Constitution." The authoring of the Constitution was a reaction to the previous twenty years of military dictatorship, and the new Constitution sought to secure individual liberty while also decentralizing and democratizing ruling power, in the hope that authoritarian dictatorship would not reemerge.[9]

Brazil's contemporary political economy is an outgrowth of the Portuguese empire's patrimonial capitalism, where "power was not exercised according to rules, but was structured through personal relationships".[10] Unlike the Athenian ideal of democracy, in which all citizens participate directly and decide policy collectively, Brazil's government is structured as a republic with elected representatives. This institutional arrangement has created a separation between the state and civil society, which has opened the doors for clientelism. Because the law-making process occurs behind closed doors, elected officials and bureaucrats can access state resources in ways that benefit certain 'clients', typically those of extraordinary social or economic relevance. The influential clients receive policy favors, and repay elected officials with votes from the groups they influence. For example, a neighborhood leader represents the views of shop owners to the local party boss, asking for laws to increase foot traffic on commercial streets. In exchange, the neighborhood leader mobilizes shop owners to vote for the political party responsible for the policy. Because this patronage operates on the basis of individual ties between patron and clients, true decision-making power is limited to a small network of party bosses and influential citizens rather than the broader public.[10][11]

In 1989, Olívio Dutra won the mayor's seat in Porto Alegre. In an attempt to encourage popular participation in government and redirect government resources towards the poor, Dutra institutionalized the PT's organizational structure on a citywide level. The result is one example of what we now know as Participatory Budgeting.

Outcomes

A World Bank paper suggests that participatory budgeting has led to direct improvements in facilities in Porto Alegre. For example, sewer and water connections increased from 75% of households in 1988 to 98% in 1997. The number of schools quadrupled since 1986.[12]:2

The high number of participants, after more than a decade, suggests that participatory budgeting encourages increasing citizen involvement, according to the paper. Also, Porto Alegre's health and education budget increased from 13% (1985) to almost 40% (1996), and the share of the participatory budget in the total budget increased from 17% (1992) to 21% (1999).[12]:3 In a paper that updated the World Bank's methodology, expanding statistical scope and analyzing Brazil's 253 largest municipalities that use participatory budgeting, researchers found that participatory budgeting reallocates spending towards health and sanitation. Health and sanitation benefits accumulated the longer participatory budgeting was used in a municipality. Participatory budgeting does not merely allow citizens to shift funding priorities in the short-term – it can yield sustained institutional and political change in the long term.[13]

The paper concludes that participatory budgeting can lead to improved conditions for the poor. Although it cannot overcome wider problems such as unemployment, it leads to "noticeable improvement in the accessibility and quality of various public welfare amenities".[12]:2

Based on Porto Alegre more than 140 (about 2.5%) of the 5,571 municipalities in Brazil have adopted participatory budgeting.[12]

For other adaptations of Participatory Budgeting around the world, see participatory budgeting by country.

Criticism

Reviewing the experience in Brazil and Porto Alegre, a World Bank paper points out that lack of representation of extremely poor people in participatory budgeting can be a shortcoming. Participation of the very poor and of the young is highlighted as a challenge.[12]:5 What are the insights regarding the opportunities for and barriers to accomplishing the goal of participatory-based budgeting? It takes leadership to flatten the organizational structure and make conscious ethical responsibilities as individuals and as committee members try to achieve the democratic goals means that the press should be present for the public, and yet the presence of the press inhibits the procedural need for robust discussion. Or, while representation is a cornerstone to participatory budgeting, a group being so large has an effect on the efficiency of the group. Participatory budgeting may also struggle to overcome existing clientelism. Other observations include that particular groups are less likely to participate once their demands have been met and that slow progress of public works can frustrate participants.[12]:3

In Chicago, participatory budgeting has been criticized for increasing funding to recreational projects while allocating less to infrastructure projects.[14]

See also

- Participatory budgeting by country

- Participatory budgeting algorithm - an algorithm that takes as input the list of projects, the available budget and the voters' preferences, and returns an allocation of the budget among the projects satisfying some pre-defined requirements.

- Participatory democracy

- Deliberative poll

- Citizens' assembly

- Participatory economics

- Participatory planning

- Participatory justice

- Programme budgeting

- Public participation

- Tax choice

- Participatory budgeting in SAFe Scaled Agile Framework

References

- Chohan, Usman W. (20 April 2016). "The 'citizen budgets' of Africa make governments more transparent". The Conversation. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- "Mission & Approach". Participatory Budgeting Project. 20 September 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- "Participatory Budgeting in Brazil". PSUpress.

- Porto de Oliveira, Osmany (10 January 2017). Internatioanl Policy Diffusion and Participatory Budgeting: Ambassadors of Participation, International Institutional and Transnational Networks. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-319-43337-0.

- Röcke, Anja (2014). Framing Citizen Participation: Participatory Budgeting in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137326669. ISBN 978-1-137-32666-9.

- Shah, Anwar (2007). Shah, Anwar (ed.). Participatory Budgeting (PDF). Washington D.C.: The World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-0-8213-6923-4. hdl:10986/6640. ISBN 978-0-8213-6924-1. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- Wainwright, H. (2003). Making a People's Budget in Porto Alegre. NACLA Report On The Americas. pp. 36(5), 37–42.

- Ganuza, Ernesto; Baiocchi, Gianpaolo (30 December 2012). "How Participatory Budgeting Travels the Globe". Journal of Public Deliberation. 8 (2). Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- Abers, Jessica (1998). "From Clientelism to Cooperation: Local Government, Participatory Policy, and Civic Organizing in Porto Alegre, Brazil". Politics & Society. 26 (4): 511–537. doi:10.1177/0032329298026004004.

- Novy, Andreas; Leubolt, Bernhard (1 October 2005). "Participatory Budgeting in Porto Alegre: Social Innovation and the Dialectical Relationship of State and Civil Society". Urban Studies. 42 (11): 2023–2036. doi:10.1080/00420980500279828. ISSN 0042-0980.

- Santos, BOAVENTURA de SOUSA (1 December 1998). "Participatory Budgeting in Porto Alegre: Toward a Redistributive Democracy". Politics & Society. 26 (4): 461–510. doi:10.1177/0032329298026004003. hdl:10316/10839. ISSN 0032-3292.

- Bhatnagar, Prof. Deepti; Rathore, Animesh; Torres, Magüi Moreno; Kanungo, Parameeta (2003), Participatory Budgeting in Brazil (PDF), Ahmedabad; Washington, DC: Indian Institutes of Management; World Bank

- "Improving Social Well-Being Through New Democratic Institutions". Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "The Pitfalls of Participatory Budgeting". Chicago Tonight | WTTW. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

Bibliography

- Sintomer, Yves; Herzberg, Carsten; Röcke, Anja (2008), From Porto Alegre to Europe: Potentials and Limitations of Participatory Budgeting (PDF), International Journal of Urban and Regional Research.

- Geissel, Brigitte; Newton, Kenneth (2012), Evaluating Democratic Innovations: Curing the Democratic Malaise?, Routledge, ISBN 9781136579950.

- Gilman, Hollie Russon (2012), Transformative Deliberations: Participatory Budgeting in the United States (PDF), Journal of Public Deliberation.

- Gilman, Hollie Russon (2016), Engaging Citizens: Participatory Budgeting and the Inclusive Governance Movement within the United States (PDF), Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, Harvard Kennedy School.

- Novy, Andreas; Leubolt, Bernhard (2005), "Participatory Budgeting in Porto Alegre: Social Innovation and the Dialectical Relationship of State and Civil Society", Urban Studies, 42 (11): 2023–2036, doi:10.1080/00420980500279828.

- Goldfrank, Benjamin (2006), Lessons from Latin American Experience in Participatory Budgeting (PDF), San Juan, Puerto Rico: ResearchGate.

- Avritzer, Leonardo (2006), "New Public Spheres in Brazil: Local Democracy and Deliberative Politics", International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 30 (3): 623–637, doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2006.00692.x.

- de Sousa Santos, Boaventura (1998), "Participatory Budgeting in Porto Alegre: Toward a Redistributive Democracy", Politics & Society, 26 (4): 461–510, doi:10.1177/0032329298026004003, hdl:10316/10839.

- Souza, Celina (2001), "Participatory budgeting in Brazilian cities: limits and possibilities in building democratic institutions", Environment and Urbanization, 13: 159–184, doi:10.1177/095624780101300112.

- Cabannes, Yves (2004), "Participatory budgeting: a significant contribution to participatory democracy", Environment and Urbanization, 16: 27–46, doi:10.1177/095624780401600104.

- Abers, Rebecca (1998), "From Clientelism to Cooperation: Local Government, Participatory Policy, and Civic Organizing in Porto Alegrem Brazil", Politics & Society, 26 (4): 511–537, doi:10.1177/0032329298026004004.

External links

- Participatory budgeting initiatives around the world (map (non-exhaustive)), Google Maps.

- The Participatory Budgeting Project – a non-profit organization that supports participatory budgeting in North America and hosts an international resource site.

- PBnetwork UK - information on participatory budgeting in the UK

- PB Scotland- Support to implement PB in Scotland

- Participatory budgeting publications and resources from What Works Scotland

- Digital tools and participatory budgeting in Scotland from The Democratic Society

- Budget Participatif Paris - PB website for the City of Paris

- Case study on the Electronic Participatory Budgeting of the city of Belo Horizonte (Brazil)

- Study with cases of Participatory Budgeting experiences in OECD countries

- www.citymayors.com - PB in Brazil

- Electronic Participatory Budgeting in Iceland - Case study

- PB in Rosario, Argentina Official Site of PB in Rosario, Argentina (Spanish).

- www.chs.ubc.ca/participatory - links to participatory budgeting articles and resources

- http://fcis.oise.utoronto.ca/~daniel_schugurensky/lclp/poa_vl.html - links to participatory budgeting articles and resources

- Participatory Budgeting Facebook Group - large participatory budgeting online community

- www.nuovomunicipio.org - Rete del Nuovo Municipio, the Italian project linking Local Authorities, scientists and local committees for promoting Participatory Democracy and Active Citizenship mainly by way of PB

- "Experimentos democráticos. Asambleas barriales y Presupuesto Participativo en Rosario, 2002-2005" - Doctoral Dissertation of Alberto Ford on Participatory Budgeting in Rosario, Argentina (Spanish).

- "More generous than you would think": Giovanni Allegretti shares insight of PB in an interviews with D+C/E+Z's Eva-Maria Verfürth, EU: DANDC.

- An interview with Josh Lerner, Executive Director of the Participatory Budgeting Project

- Participatory budgeting site of Cambridge, Massachusetts