Ostracon

An ostracon (Greek: ὄστρακον ostrakon, plural ὄστρακα ostraka) is a piece of pottery, usually broken off from a vase or other earthenware vessel. In an archaeological or epigraphical context, ostraca refer to sherds or even small pieces of stone that have writing scratched into them. Usually these are considered to have been broken off before the writing was added; ancient people used the cheap, plentiful and durable broken pieces of pottery around them as convenient places to place writing for a wide variety of purposes, mostly very short inscriptions, but in some cases surprisingly long.

_-_Photo_by_Giovanni_Dall'Orto%2C_Nov_9_2009.jpg)

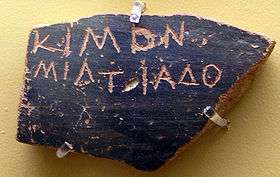

Ostracism

In Classical Athens, when the decision at hand was to banish or exile a certain member of society, citizen peers would cast their vote by writing the name of the person on the sherd of pottery; the vote was counted and, if unfavorable, the person was exiled for a period of ten years from the city, thus giving rise to the term ostracism.

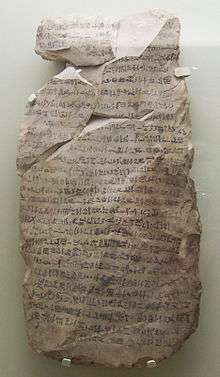

Egyptian limestone and potsherd ostraca

Anything with a smooth surface could be used as a writing surface. Generally discarded material, ostraca were cheap, readily available and therefore frequently used for writings of an ephemeral nature such as messages, prescriptions, receipts, students' exercises and notes. Pottery sherds, limestone flakes,[1] and thin fragments of other stone types were used, but limestone sherds, being flaky and of a lighter colour, were most common. Ostraca were typically small, covered with just a few words or a small picture drawn in ink;[2] but the tomb of the craftsman Sennedjem at Deir el Medina contained an enormous ostracon inscribed with the Story of Sinuhe.[1]

The importance of ostraca for Egyptology is immense. The combination of their physical nature and the Egyptian climate have preserved texts, from the medical to the mundane, which in other cultures were lost.[3] These can often serve as better witnesses of everyday life than literary treatises preserved in libraries.

Deir el-Medina Medical Ostraca

The many ostraca found at Deir el-Medina provide a deeply compelling view into the medical workings of the New Kingdom. These ostraca have shown that, like other Egyptian communities, the workmen and inhabitants of Deir el-Medina received care through a combination of medical treatment, prayer, and magic.[4] Nevertheless, the records at Deir el-Medina indicate some level of division, as records from the village note both a “physician” who saw patients and prescribed treatments, and a “scorpion charmer” who specialized in magical cures for scorpion stings.[5]

The ostraca from Deir el-Medina also differed in their circulation. Magical spells and remedies were widely distributed among the workmen; there are even several cases of spells being sent from one worker to another, with no “trained” intermediary.[6][7] Written medical texts appear to have been much rarer, with only a handful of ostraca containing prescriptions, indicating that the trained physician mixed the more complicated remedies himself. There are also several documents that show the writer sending for medical ingredients, but it is unknown whether these were sent according to a physician’s prescription, or to fulfill a home remedy.[8]

Saqqara Dream Ostraca

From 1964–1971, Bryan Emery excavated at Saqqara in search of Imhotep's tomb; instead, the extensive catacombs of animal mummies were uncovered. Apparently it was a pilgrim site, with as many as 1½ million ibis birds interred (as well as cats, dogs, rams, and lions). This 2nd-century BC site contained extensive pottery debris from the site offerings of the pilgrims.

Emery's excavations uncovered the "Dream Ostraca", created by a scribe named Hor of Sebennytos. A devotee of the god Thoth, he lived adjacent to Thoth's sanctuary at the entrance to the North Catacomb and worked as a "proto-therapist", advising and comforting clients. He transferred his divinely-inspired dreams onto ostraca. The Dream Ostraca are 65 Demotic texts written on pottery and limestone.[9]

Biblical period ostraca

Famous ostraca for Biblical archaeology have been found at:

- Arad, Israel, or Tel Arad

- Lachish

- Mesad Hashavyahu

- Ostraca House at Samaria

- Elah Fortress at Khirbet Qeiyafa[10]

Additionally, the lots drawn at Masada are believed to have been ostraca, and some potsherds resembling the lots have been found.

In October 2008, Israeli archaeologist, Yosef Garfinkel of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has discovered what he says to be the earliest known Hebrew text. This text was written on an Ostracon sherd; Garfinkel believes this sherd dates to the time of King David from the Old Testament, about 3,000 years ago. Carbon dating of the Ostracon and analysis of the pottery have dated the inscription to be about 1,000 years older than the Dead Sea Scrolls. The inscription has yet to be deciphered, however, some words, such as king, slave and judge have been translated. The sherd was found about 20 miles southwest of Jerusalem at the Elah Fortress in Khirbet Qeiyafa, the earliest known fortified city of the biblical period of Israel.[10]

See also

- List of artifacts significant to the Bible

- Ostraca House

- Ostracism

- Ostracon of Senemut and Djehuty

- Potsherd

- Satirical ostraca

- Soleto Map

Notes

- Donadoni, Sergio, ed. (1997), The Egyptians, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 78, ISBN 0-226-15555-2.

- Klauck, Hans-Josef (2006), Ancient Letters And the New Testament: A Guide to Context and Exegesis, Baylor University Press, p. 45, ISBN 1-932792-40-6.

- Chauveau, Michel (2000), Egypt in the Age of Cleopatra: History and Society Under the Ptolemies, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, p. 7, ISBN 0-8014-8576-2.

- McDowell 2002, p. 53.

- Janssen, Jac. J. (1980). "Absence from Work by the Necropolis Workmen of Thebes". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 8: 127–152.

- Lesko, p. 68

- McDowell 2002, p. 106.

- McDowell 2002, p. 57.

- Reeves (2000).

- "Archeologist finds 3,000-year old Hebrew text", CNN, October 30, 2008

References

- Parkinson, Richard; Diffie, W.; Fischer, M.; Simpson, R.S. (1999), Cracking Codes: The Rosetta Stone, and Decipherment, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-22306-3.

- Reeves, Nicholas (2000), Ancient Egypt: The Great Discoveries: A Year-by-Year Chronicle, London: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-05105-4. (Specifically, "1964–71: The Sacred Animal Necropolis, Saqqara"; and "1964–65: A Statue Finds Its Face".)

- McDowell, A.G. Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2002).

- Forsdyke, Sara, Exile, Ostracism, and Democracy: The Politics of Expulsion in Ancient Greece (Princeton, PUP, 2005).

- Litinas, Nikos, Greek Ostraca from Chersonesos, Crete: Ostraca Cretica Chersonesi (O.Cret.Chers.) (Wien: Holzhausen, 2008) (Tyche. Supplementband; 6).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ostraka. |

- Ostraca

- The Ostracon, the research publication of the Egyptian Study Society.

- Archeologist discovers 3000-year old ostracon

- Prize Find: Oldest Hebrew Inscription Biblical Archaeology Review