Osip Mandelstam

Osip Emilyevich Mandelstam[1] (Russian: О́сип Эми́льевич Мандельшта́м, IPA: [ˈosʲɪp ɪˈmʲilʲjɪvʲɪtɕ məndʲɪlʲˈʂtam]; 14 January [O.S. 2 January] 1891 – 27 December 1938) was a Russian and Soviet poet and essayist of Jewish origin. He was the husband of Nadezhda Mandelstam and one of the foremost members of the Acmeist school of poets. He was arrested by Joseph Stalin's government during the repression of the 1930s and sent into internal exile with his wife.

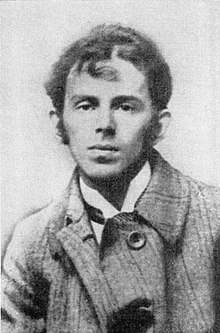

Osip Mandelstam | |

|---|---|

Osip Mandelstam in 1914 | |

| Born | Osip Emilyevich Mandelstam 14 January [O.S. 2 January] 1891 Warsaw, Congress Poland, Russian Empire |

| Died | 27 December 1938 (aged 47) Transit Camp "Vtoraya Rechka" (near Vladivostok), Soviet Union |

| Occupation | Poet, Essayist |

| Literary movement | Acmeist poetry |

Given a reprieve of sorts, they moved to Voronezh in southwestern Russia. In 1938 Mandelstam was arrested again and sentenced to five years in a corrective-labour camp in the Soviet Far East. He died that year at a transit camp near Vladivostok.[2]

Life and work

Mandelstam was born in Warsaw, Congress Poland, Russian Empire to a wealthy Polish-Jewish family.[3] His father, a leather merchant by trade, was able to receive a dispensation freeing the family from the Pale of Settlement. Soon after Osip's birth, they moved to Saint Petersburg.[3] In 1900, Mandelstam entered the prestigious Tenishev School. His first poems were printed in 1907 in the school's almanac.

In April 1908, Mandelstam decided to enter the Sorbonne in Paris to study literature and philosophy, but he left the following year to attend the University of Heidelberg in Germany. In 1911, he decided to continue his education at the University of Saint Petersburg, from which Jews were excluded. He converted to Methodism and entered the university the same year.[4] He did not complete a formal degree.[5]

Mandelstam's poetry, acutely populist in spirit after the first Russian revolution in 1905, became closely associated with symbolist imagery. In 1911, he and several other young Russian poets formed the "Poets' Guild", under the formal leadership of Nikolai Gumilyov and Sergei Gorodetsky. The nucleus of this group became known as Acmeists. Mandelstam wrote the manifesto for the new movement: The Morning Of Acmeism (1913, published in 1919).[6] In 1913 he published his first collection of poems, The Stone;[7] it was reissued in 1916 under the same title, but with additional poems included.

Marriage and family

Mandelstam was said to have had an affair with the poet Anna Akhmatova. She insisted throughout her life that their relationship had always been a very deep friendship, rather than a sexual affair.[8] In the 1910s, he was in love, secretly and unrequitedly, with a Georgian princess and St. Petersburg socialite Salomea Andronikova, to whom Mandelstam dedicated his poem "Solominka" (1916).[9]

In 1922, Mandelstam married Nadezhda Khazina in Kiev, Ukraine, where she lived with her family,[10] but the coupled settled in Moscow.[3] He continued to be attracted to other women, sometimes seriously. Their marriage was threatened by his falling in love with other women, notably Olga Vaksel in 1924-25 and Mariya Petrovykh in 1933-34.[11]

During Mandelstam's years of imprisonment, 1934–38, Nadezhda accompanied him into exile. Given the real danger that all copies of Osip's poetry would be destroyed, she worked to memorize his entire corpus, as well as to hide and preserve select paper manuscripts, all the while dodging her own arrest.[12] In the 1960s and 1970s, as the political climate thawed, she was largely responsible for arranging clandestine republication of Mandelstam's poetry.[13]

Career, political persecution and death

In 1922, Mandelstam and Nadezhda moved to Moscow. At this time, his second book of poems, Tristia, was published in Berlin.[7] For several years after that, he almost completely abandoned poetry, concentrating on essays, literary criticism, memoirs The Noise Of Time, Feodosiya - both 1925; (Noise of Time 1993 in English) and small-format prose The Egyptian Stamp (1928). As a day job, he translated literature into Russian (19 books in 6 years), then worked as a correspondent for a newspaper.

.jpg)

In the autumn of 1933, Mandelstam composed the poem "Stalin Epigram", which he read at a few small private gatherings in Moscow. The poem was a sharp criticism of the "Kremlin highlander". Six months later, in 1934, Mandelstam was arrested. But, after interrogation about his poem, he was not immediately sentenced to death or the Gulag, but to exile in Cherdyn in the Northern Ural, where he was accompanied by his wife. After he attempted suicide, and following an intercession by Nikolai Bukharin, the sentence was lessened to banishment from the largest cities.[14] Otherwise allowed to choose his new place of residence, Mandelstam and his wife chose Voronezh.

This proved a temporary reprieve. In the next years, Mandelstam wrote a collection of poems known as the Voronezh Notebooks, which included the cycle Verses on the Unknown Soldier. He also wrote several poems that seemed to glorify Stalin (including "Ode To Stalin"). However, in 1937, at the outset of the Great Purge, the literary establishment began to attack him in print, first locally, and soon after from Moscow, accusing him of harbouring anti-Soviet views.

Second arrest and death

Early the following year, Mandelstam and his wife received a government voucher for a holiday not far from Moscow; upon their arrival in May 1938, he was arrested on 5 May (ref. camp document of 12 October 1938, signed by Mandelstam) and charged with "counter-revolutionary activities". Four months later, on 2 August 1938,[15] Mandelstam was sentenced to five years in correction camps. He arrived at the Vtoraya Rechka (Second River) transit camp near Vladivostok in Russia's Far East and managed to get a note out to his wife asking for warm clothes; he never received them. He died from cold and hunger. His death was described later in a short story "Sherry Brandy" by Varlam Shalamov.

Mandelstam's own prophecy was fulfilled: "Only in Russia is poetry respected, it gets people killed. Is there anywhere else where poetry is so common a motive for murder?" Nadezhda wrote memoirs about her life and times with her husband in Hope against Hope (1970) [12] and Hope Abandoned.[13] She also managed to preserve a significant part of Mandelstam's unpublished work.[14]

Posthumous reputation and influence

- In 1956, during the Khrushchev thaw, Mandelstam was rehabilitated and exonerated from the charges brought against him in 1938.

- The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation aired Hope Against Hope, a radio dramatization about Mandelstam's poetry based on the book of the same title by Nadezhda Mandelstam, on 1 February 1972. The script was written by George Whalley, a Canadian scholar and critic, and the broadcast was produced by John Reeves.

- In 1977, a minor planet, 3461 Mandelstam, discovered by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh, was named after him.[16]

- On 28 October 1987, during the administration of Mikhail Gorbachev, Mandelstam was also exonerated from the 1934 charges and thus fully rehabilitated.[17]

- In 1998, a monument was put up in Vladivostok in his memory.[2]

Selected poetry and prose collections

- 1913 Kamen (Stone)

- 1922 Tristia

- 1923 Vtoraia kniga (Second Book)

- 1925 Shum vremeni (The Noise Of Time) Prose

- 1928 Stikhotvoreniya 1921–1925 (Poems 1921-1925)

- 1928 Stikhotvoreniya (Poems)

- 1928 O poesii (On Poetry)

- 1928 Egipetskaya marka (The Egyptian Stamp)

- 1930 Chetvertaya proza, (The Fourth Prose). Not published in Russia until 1989

- 1930-34 Moskovskiye tetradi (Moscow Notebooks)

- 1933 Puteshestviye v Armeniyu (Journey to Armenia)

- 1933 Razgovor o Dante, (Conversation about Dante); published in 1967[18]

- Voronezhskiye tetradi (Voronezh Notebooks), publ. 1980 (ed. by V. Shveitser)

Selected translations

- Ahkmatova, Mandelstam, and Gumilev (2013) Poems from the Stray Dog Cafe, translated by Meryl Natchez, with Polina Barskova and Boris Wofson, hit & run press, (Berkeley, CA) ISBN 0936156066

- Mandelstam, Osip and Struve, Gleb (1955) Sobranie sočinenij (Collected works). New York OCLC 65905828

- Mandelstam, Osip (1973) Selected Poems, translated by David McDuff, Rivers Press (Cambridge) and, with minor revisions, Farrar, Straus and Giroux (New York)

- Mandelstam, Osip (1973) The Complete Poetry of Osip Emilevich Mandelstam, translated by Burton Raffel and Alla Burago. State University of New York Press (USA)

- Mandelstam, Osip (1973) The Goldfinch. Introduction and translations by Donald Rayfield. The Menard Press

- Mandelstam, Osip (1974). Selected Poems, translated by Clarence Brown and W. S. Merwin. NY: Atheneum, 1974.

- Mandelstam, Osip (1976) Octets 66-76, translated by Donald Davie, Agenda vol. 14, no. 2, 1976.

- Mandelstam, Osip (1977) 50 Poems, translated by Bernard Meares with an Introductory Essay by Joseph Brodsky. Persea Books (New York)

- Mandelstam, Osip (1980) Poems. Edited and translated by James Greene. (1977) Elek Books, revised and enlarged edition, Granada/Elek, 1980.

- Mandelstam, Osip (1981) Stone, translated by Robert Tracy. Princeton University Press (USA)

- Mandelstam, Osip (1993, 2002) The Noise of Time: Selected Prose, translated by Clarence Brown, Northwestern University Press; Reprint edition ISBN 0-8101-1928-5

- Mandlestam, Osip (2012) "Stolen Air", translated by Christian Wiman. Harper Collins (USA)

- Mandelstam, Osip (2018) Concert at a Railway Station. Selected Poems, translated by Alistair Noon. Shearsman Books (Bristol)

Further reading

- Coetzee, J.M. "Osip Mandelstam and the Stalin Ode", Representations, No.35, Special Issue: Monumental Histories. (Summer, 1991), pp. 72–83.

- Davie, Donald (1977) In the Stopping Train Carcanet (Manchester)

- Freidin, Gregory (1987) A Coat of Many Colors: Osip Mandelstam and His Mythologies of Self-Presentation. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London

- Анатолий Ливри, "Мандельштам в пещере Заратустры", - в Вестнике Университета Российской Академии Образования, ВАК, 1 – 2014, Москва, с. 9 – 21. http://anatoly-livry.e-monsite.com/medias/files/mandelstam-livry026.pdf Copie of Nietzsche.ru : http://www.nietzsche.ru/influence/literatur/livri/mandelstam/%5B%5D. Version française : Anatoly Livry, Nietzscheforschung, Berlin, Humboldt-Universität, 2013, Band 20, S. 313-324 : http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/nifo.2013.20.issue-1/nifo.2013.20.1.313/nifo.2013.20.1.313.xml

- Dr. Anatoly Livry, « Mandelstam le nietzschéen: une origine créative inattendue » dans Журнал Вісник Дніпропетровського університету імені Альфреда Нобеля. Серія «Філологічні науки» зареєстровано в міжнародних наукометричних базах Index Copernicus, РИНЦ, 1 (13) 2017, Університет імені Альфреда Нобеля, м. Дніпро, The Magazine is inscribed by the Higher Certifying Commission on the index of leading reviewing scientific periodicals for publications of main dissertation of academic degree of Doctor and Candidate of Science, p. 58-67. http://anatoly-livry.e-monsite.com/medias/files/1-13-2017.pdf%5B%5D

- MacKay, John (2006) Inscription and Modernity: From Wordsworth to Mandelstam. Bloomington: Indiana University Press ISBN 0-253-34749-1

- Nilsson N. A. (1974) Osip Mandel’štam: Five Poems. (Stockholm)

- Platt, Kevin, editor (2008) Modernist Archaist: Selected Poems by Osip Mandelstam [19]

- Riley, John (1980) The Collected Works. Grossteste (Derbyshire)

- Ronen, O. (1983) An Аpproach to Mandelstam. (Jerusalem)

- Mikhail Berman-Tsikinovsky (2008), play "Continuation of Mandelstam" (published by Vagrius, Moskow. ISBN 978-5-98525-045-9)

References

- Also romanized Osip Mandelstam, Ossip Mandelstamm

- Delgado, Yolanda; RIR, specially for (2014-07-18). "The final days of Russian writers: Osip Mandelstam". www.rbth.com. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- "1938: A poet who mocked Stalin dies in the gulag". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2011-08-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Vitaly Charny, "Osip Emilyevich Mandelshtam (1889-1938) Russian Poet"

- Brown, C.; Mandelshtam, O. (1965). "Mandelshtam's Acmeist Manifesto". Russian Review. 24 (1): 46–51. doi:10.2307/126351. JSTOR 126351.

- ""It gets people killed": Osip Mandelstam and the perils of writing poetry under Stalin". www.newstatesman.com. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- Feinstein, Elaine. Anna of All the Russias, New York: Vintage Press, 2007.

- Zholkovsky, Alexander (1996), Text Counter Text: Rereadings in Russian Literary History, p. 165. Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-2703-1.

- Morley, David (1991) Mandelstam Variations Littlewood Press p75 ISBN 978-0-946407-60-6

- Clarence Brown, Mandelstam, Cambridge University Press, 1973

- Nadezhda Mandelstam (1970, 1999) Hope against Hope ISBN 1-86046-635-4

- Nadezhda Mandelstam Hope Abandoned ISBN 0-689-10549-5

- Ronen, O. (2007). "Mandelshtam, Osip Emilyevich.". In M. Berenbaum and F. Skolnik (ed.). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Detroit (2 ed.). Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 462–464.

- Extract from court protocol No. 19390/Ts

- Dictionary of Minor Planet Names, p. 290

- Kuvaldin, Y. (Юрий Кувалдин): Улица Мандельштамa Archived 2007-10-17 at the Wayback Machine, повести. Издательство "Московский рабочий", 1989, 304 p. In Russian. URL last accessed 20 October 2007.

- Freidin, G.: Osip Mandelstam, Encyclopædia Britannica, 2001. Accessed 20 October 2007.

- Modern Archaist: Selected Poems by Mandelstam

External links

- Poetry Foundation. Poems and biography. Accessed 2010-09-11

- Finding aid to the Osip Mandel'shtam Papers at the Princeton University Library. Accessed 2010-09-11

- Osip Mandelstam poetry at Stihipoeta

- Academy of American Poets, Biography of Mandelstam. Accessed 2010-09-11

- Osip Mandelstam: New Translations (e-chapbook from Ugly Duckling Presse)

- Songs on poetry by Osip Mandelshtam on YouTube, Poems "How on Kama the river" and "Life fell" dedicated to the wife of the poet, Nadezhda Mandelstam; music and performance by Larisa Novoseltseva.

- The Poems of Osip Mandelstam (ebook of poems in translation, mostly from the 1930s)

- English translation of Osip Mandelstam's longest and only free verse poem, "He Who Had Found a Horseshoe," in the New England Review

- English translation of Osip Mandelstam's poems "Menagerie" (1915) and "The Sky is Pregnant with the Future" (1923, 1929) in the Colorado Review

- Works by or about Osip Mandelstam at Internet Archive

- Works by Osip Mandelstam at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)