Operation Solomon

Operation Solomon (Hebrew: מבצע שלמה, Mivtza Shlomo) was a covert Israeli military operation to airlift Ethiopian Jews to Israel from May 24 to May 25, 1991. Non-stop flights of 35 Israeli aircraft, including Israeli Air Force C-130s and El Al Boeing 747s, transported 14,325 Ethiopian Jews to Israel in 36 hours.[1] One of the aircraft, an El Al 747, carried at least 1,088 people, including two babies who were born on the flight, and holds the world record for the most passengers on an aircraft.[2]

| Operation Solomon | |

|---|---|

| Location | Ethiopia–Israel |

| Planned by | Israeli government and Israeli Defense Forces |

| Objective | To airlift Ethiopian Jews to Israel |

| Outcome | Transported 14,325 Ethiopian Jews to Israel in 36 hours |

History

Operation Solomon was the third Aliyah mission from Ethiopia to Israel. Before Operation Solomon, there was Operation Moses and Operation Joshua, which were two of the other ways that Ethiopian Jews could leave before they were forced to put an end to these type of programs. In between the time when these operations came to an end and Operation Solomon began, a very small number of Ethiopian Jews were able to leave and go to Israel.[3]

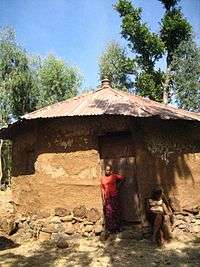

In 1991, the sitting Ethiopian government of Mengistu Haile Mariam was close to being toppled with the military successes of Eritrean and Tigrean rebels, threatening Ethiopia with dangerous political destabilization. World Jewish organizations, such as the American Association for Ethiopian Jews (AAEJ), and Israel were concerned about the well-being of the Ethiopian Jews, known as Beta Israel, residing in Ethiopia. The majority of them were living in the Gondar region of the Ethiopian Highlands and were mostly farmers and artisans.[4] Also, the Mengistu regime had made mass emigration difficult for Beta Israel, and the regime's dwindling power presented an opportunity for those wanting to emigrate to Israel. In 1990, the Israeli government and Israeli Defense Forces, aware of Ethiopia’s worsening political situation, made covert plans to airlift the Jews to Israel. America became involved in the planning of Operation Solomon after it was brought to the US government's attention from American Jewish leaders from the American Association for Ethiopian Jews that the Ethiopian Jews were living in danger. [5]

The American government was also involved in the organization of the airlift. The decision of the Ethiopian government to allow all the Falshas to leave the country at once was largely motivated by a letter from President George H. W. Bush, who had some involvement with Operations Joshua and Moses. [5] Previous to this, Mengistu intended to allow emigration only in exchange for weaponry.[1]

Also involved in the Israeli and Ethiopian governments' attempts to facilitate the operation was a group of American diplomats led by Senator Rudy Boschwitz, including Irvin Hicks, a Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs; Robert Frasure, the Director of the African Affairs at the White House National Security Council; and Robert Houdek the Chargé d'Affaires of the United States Embassy in Addis Ababa. Boschwitz had been sent as a special emissary of President Bush, and he and his team met with the government of Ethiopia to aid Israel in the arranging of the airlift. In addition, Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Herman Cohen also played an important role, as he was the international mediator of the civil war in Ethiopia.[6] Cohen struck a deal with Mengistu that as long as Ethiopians would have an understanding with the rebels, change their human rights and emigration policy and change their communist economic practice.[5] In response to the efforts of the diplomats, acting President of Ethiopia Tesfaye Gebre-Kidan made the ultimate decision to allow the airlift.[7] The negotiations surrounding the operation led to the eventual London roundtable discussions, which established a joint declaration by the Ethiopian combatants who then agreed to organize a conference to select a transitional government.[6] $35 million was raised by the Jewish community to give to the government in Ethiopia so that the Jews could come over to Israel. The money went to the airport expenses in Addis Ababa.[8]

Lead-up: Internal Debate within the Jewish community

In the decade leading up to the operation, there was a heated division within the Israeli community over whether to accept the Ethiopians. The reasoning against bringing in Ethiopians proved to be very diverse. Some Jews within Israel feared a "shanda fur di goyim" (embarrassment in front of the non-Jews), and thus aimed to avoid the issue of stirring up controversy by ignoring the pleas of the Ethiopian Jews.[9] Others advocated for the operation, but avoided public demonstrations that might lead to arrests and further public controversy. Taking a completely different approach, others within the Israeli community claimed that there was a cultural divide which would make the integration process untenable; these included Director General of the Jewish Agency's Department of Immigration and Absorption Yehuda Dominitz, who likened this displacement to "taking a fish out of water".[10] Still others elaborated on this vague notion with more provocative claims, such as World Zionist Organization writer Malkah Raymist, who argued that the Ethiopians' "mental outlook is that of children... It would take several years before they could be educated towards a minimum of progressive thinking."[11] However, ultimately, these counter arguments were in vain, as the Israeli government went ahead and conducted the airlift anyway, and the jubilant Ethiopians were greeted as they exited the planes by thousands of joyous Israelis.[12]

Operation

The operation was overseen by the Prime Minister at the time, Yitzhak Shamir.[4] It was kept secret by military censorship.[1] Operation Solomon was sped up with tremendous help from the AAEJ. In 1989, the AAEJ accelerated the process of the Aliyah because Ethiopian-Israeli relations were in the right place. Susan Pollack, who was the director of the AAEJ in Addis Ababa, fought for Operation Solomon to happen sooner rather than later. Israel, who had a gradual plan for this operation, and the US were given a graphic report from Pollack that informed both countries of the terrible conditions that the Ethiopian Jews were living in.[5] The organization went right ahead and got transportation like buses and trucks to have the people of Gondar quickly come to Addis Ababa.[4] To get the Jews in Addis Ababa, many of the Jews that came from Gondar had to venture hundreds of miles by car, horses, and by foot.[13] Some had things taken by thieves on the way, and some were even killed. By December 1989, around 2,000 Ethiopian Jews made their way by foot from their village in the Gondar highlands to the capital and many more came to join them by 1991.[5]

In order to accommodate as many people as possible, airplanes were stripped of their seats, and due to the low body weight and minimal baggage of the refugees, up to 1,086 passengers were boarded on a single plane. May 24, 1991 also happened to be a Friday, which begins the Jewish Shabbat,[14] during which transportation is not normally used. This made more vehicles available for the mission, as Jewish Religious Law permits breaking the Sabbath traditions for saving lives.[15]

Many of the immigrants came with nothing except their clothes and cooking instruments, and were met by ambulances, with 140 frail passengers receiving medical care on the tarmac. Several pregnant women gave birth on the plane, and they and their babies were rushed to the hospital.[16] Before Operation Solomon took place, many of the Jews there were at a high risk of infection from diseases, especially HIV. The Jews that were left behind had an even higher risk at the infection because the rate of it kept increasing.[5] After a few months, around 20,000 Jews had made their way over. While they were there, they were struggling for basic resources like food and warmth. They thought they would see their families right away.[4]

Upon arrival, the passengers cheered and rejoiced. Twenty-nine-year-old Mukat Abag said, "We didn't bring any of our clothes, we didn't bring any of our things, but we are very glad to be here."[1]

Operation Solomon airlifted almost twice as many Ethiopian Jews to Israel as Operation Moses. Between 1990 and 1999, over 39,000 Ethiopian Jews entered Israel.[3]

World record

The operation set a world record for most passengers on an aircraft when an El Al 747 carried well over 1,000 people to Israel. The record itself is uncontested, but the number of passengers is unclear: Guinness World Records put the number at 1,088, including two babies who were born on the flight. It noted that contemporary reports cite numbers as low as 1,078 and as high as 1,122.[2][17][1]

Aftermath: Socio-economic strife

Since being transported to Israel, the vast majority of these Beta Israel transfers have struggled to find work within the region. 2006 estimates suggest that up to 80 percent of adult immigrants from Ethiopia are unemployed and forced to live off national welfare payments.[18] Unemployment figures improved significantly by 2016, with only 20 percent of men and 26 percent of women being unemployed.[19] This struggle can be explained by a number of potential factors. Firstly, the transition from the rural, largely illiterate lands of Ethiopia to a highly urban workforce in Israel has proved difficult, especially when considering the fact that most Ethiopian Jews do not speak Hebrew and are in competition with other, more highly skilled immigrant workers. Nevertheless, the fact that the younger generations of Ethiopian Israelites, who have grown up and been educated in Israel and possess graduate degrees and more forms of formal training, still have a disproportionate amount of trouble finding work suggests that other factors may be at play, including potential racial or even religious bias, given that there has been debate over whether or not Ethiopian Jews should be considered Jewish in the first place.[20]

In popular culture

Fig Tree (2018), directed by Alamork Marsha about her own experience with Operation Solomon.[21]

References

- "Ethiopian Jews and Israelis Exult as Airlift Is Completed". May 26, 1991. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- "Most passengers on an aircraft". https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/most-passengers-on-an-aircraft/. Retrieved 2020-05-25. External link in

|website=(help) - "Operation Solomon". www.zionism-israel.com. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- "Yitzhak Shamir's Greatest Legacy Is Operation Solomon, the May 1991 Airlift of Thousands of Ethiopian Jews – Tablet Magazine". www.tabletmag.com. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- Spector, Stephen (2005-03-15). Operation Solomon: The Daring Rescue of the Ethiopian Jews. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199839100.

operation solomon.

- "Remarks at the Awards Presentation Ceremony for Emigration Assistance to Ethiopian Jews June 4, 1991". EBSCOhost. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- "Statement by Press Secretary Fitzwater on the Airlift of Ethiopian Jews to Israel May 24, 1991". EBSCOhost. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- Pertman, Adam (June 30, 1991). "Wandering no more For the thousands of Ethiopian Jews who have immigrated to Israel over the last two decades, assimilation has been a wrenching process. Yet, they are fulfilling a life-long dream to live in the Holy Land, and they have few regrets". ProQuest 294602131. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Galchinsky, Michael (2004). "Operation Solomon: The Daring Rescue of the Ethiopian Jews (review)". American Jewish History. 92 (4): 522–524. doi:10.1353/ajh.2007.0005. ISSN 1086-3141.

- BenEzer, Gadi (2017), "Ethiopian Jews Encounter Israel", The Migration Journey, Routledge, pp. 180–198, doi:10.4324/9781315133133-8, ISBN 9781315133133

- 1959-, Bard, Mitchell Geoffrey (2002). From tragedy to triumph: the politics behind the rescue of Ethiopian Jewry. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. ISBN 9780313076282. OCLC 651854863.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Beauchamp, Zack (6 May 2015). "The massive protests by Tel Aviv's Ethiopian Jews hold a crucial lesson for Israel". Vox.

- Ayalen, Sophia (May 2, 1992). "To Live in Deed". ProQuest 321058470. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Ethiopia Virtual Jewish Tour". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- Brinkley, Joel. "Ethiopian Jews and Israelis Exult as Airlift Is Completed". New York Times. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- "EXODUS". EBSCOhost. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- Cf. Lungen, Paul. Canadian Jewish News, November 17, 2005.

- Barkat, Amiram (29 May 2006). "Ethiopian Immigrants Not Being Prepared for New Life in Israel". haaretz.com.

- https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/ethiopian-jews-suffer-racism-in-israel/1526782

- editor., Kemp, Adriana (2014). Israelis in conflict : hegemonies, identities and challenges. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1845196745. OCLC 903482816.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Operation Solomon drama 'Fig Tree' heads to Toronto film fest". Retrieved 2018-12-01.

Further reading

- Naomi Samuel (1999). The Moon is Bread. Gefen Publishing House. ISBN 965-229-212-5

- Shmuel Yilma (1996). From Falasha to Freedom: An Ethiopian Jew's Journey to Jerusalem. Gefen Publishing House. ISBN 965-229-169-2

- Alisa Poskanzer (2000). Ethiopian Exodus. Gefen Publishing House. ISBN 965-229-217-6

- Baruch Meiri (2001). The Dream Behind Bars: The Story of the Prisoners of Zion from Ethiopia. Gefen Publishing House. ISBN 965-229-221-4

- Stephen Spector (2005). Operation Solomon: The Daring Rescue of the Ethiopian Jews. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517782-4; reviewed by George Jochnowitz in the September/October 2005 issue of Midstream

- Ricki Rosen (2006). Transformations: From Ethiopia to Israel. ISBN 965-229-377-6

- Gad Shimron (2007). Mossad Exodus: The Daring Undercover Rescue of the Lost Jewish Tribe . Gefen Publishing House. ISBN 978-965-229-403-6

- Asher Naim (2003). "Saving the Lost Tribe: The Rescue and Redemption of the Ethiopian Jews" Ballantine Publishing Group. ISBN 0-345-45081-7

External links

- Jewish Agency for Israel The Jewish Agency has been responsible for the aliyah from around the world since 1948

_-_LINE_OF_ETHIOPIAN_IMMIGRANTS_STREAMING_OUT_OF_THE_HERCULES.jpg)