Online credentials for learning

Online credentials for learning are digital credentials that are offered in place of traditional paper credentials for a skill or educational achievement. They are directly linked to the accelerated development of internet communication technologies, the development of digital badges, electronic passports and massive open online courses (MOOCs).[1]

History

Online credentials have their origin in the concept of open educational resources (OER), which was invented during the Forum on Open Courseware for Higher Education in Developing Countries held in 2002 at UNESCO.[2] Over the next decade the OER concept gained significant traction, and this was confirmed by the World Open Educational Resources (OER) Congress organized by UNESCO in 2012. One of the outcomes of the congress was to encourage the open licensing of educational materials produced with public funds. Creative Commons licensing provides the necessary standardization for copyright permissions, with a strong emphasis on the shift towards sharing and open licensing.[1]

Digital credentials ecosystem

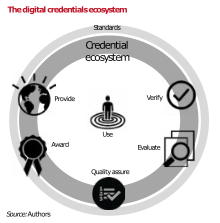

The digital credentials ecosystem is made up of a combination of traditional (better established) systems and flexible and dynamic (less regulated and new) systems. The challenge for the recognition of learning is that the pace of development, and also the point of departure, of these two aspects is different. The system is made up of seven interrelated sectors and groups of stakeholders, anchored to specific functions in the digital credentials environment.[3]

- Use. These are the users of credentials, notably learners, who are placed at the centre of the system.[4][3] Providers and employers can also be users.

- Provide. Referring to education and training institutions and the emerging variety of for-profit and non-profit digital platforms, such as Coursera, FutureLearn, Credley, Verifdiploma and Mozilla.

- Award. Awarding bodies in the traditional sense are institutions and professional bodies. Employers, MOOCs, and in some instances also the owners/hosts of digital platforms such as IMS Global are also considered.

- Quality assure. The lack of quality assurance poses a significant threat to the credibility of digital credentials, and sets constraints on the flexibility of traditional degrees.

- Evaluate. The evaluation of credentials has been owned by credential evaluation agencies, such as the ENIC-NARIC network and some qualifications authorities.

- Verify. The range of both public and private verification agencies that have emerged in the last five years has increased and can be attributed to the affordances related to the digitization of credentials.

- Convene. International agencies and open communities and networks have a role to play within the context.[3]

Test-based credentials

Test-based credentials have gained popularity both in the online market, and in programming and highly technical tasks. These credentials are earned by taking multiple-choice or project-based tests in various skill areas.[1]

Online badges

Badges allow individuals to demonstrate job skills, educational accomplishments, online course completion or just about anything else that a badge creator decides. The concept is still quite flexible and undefined. Badges support capturing and translating learning across contexts; encouraging and motivating participation and learning outcomes; and formalizing and enhancing existing social aspects of informal and interest-driven learning.[5][1]

In Europe, since 2000, the work of the CEDEFOP[6][7][8] and the adoption in 2009 of the European Guidelines for Validating Non-formal and Informal Learning[7] have supported the development of policies and programmes periodically monitored through the European inventory on validation of non-formal and informal learning.[1]

Online or digital badges are not dissimilar to the concept of the Europass CV. With open badges the process is more decentralized and removed from the traditional quality assurance bodies:[1][9][1] A criticism of open badges, such as those developed by Mozilla, is that they lack a credible quality assurance component. On the positive side, open badges are free and allow for the inclusion of various forms of learning, including non-formal and informal learning.[1]

Online certificates

Among alternative credentials, online certificates currently command the highest value, and are nearly comparable to a traditional degree. Earning an online certificate from an online college, a company or an industry-specific organization is typically much more involved than for the other credentials. The certificates are often connected to specific job functions. Many of these certificates have been created by companies such as Cisco, IBM or Microsoft to meet their own needs or the needs of their customers.[1]

Future developments

Future challenges for the concept that have been identified include the way issuing and earning process for the badges is quality-assured; the centralization (or not) of the badge-issuing process and the legitimacy of any organization that takes charge of it; the way badge issuers are using the open standard to ensure that the learners stay in control and badges remain interoperable; and the way badges will be used and recognized by education institutions, enterprises and individuals.[1]

Sources

![]()

References

- Keevy, James; Chakroun, Borhene (2015). Level-setting and recognition of learning outcomes: The use of level descriptors in the twenty-first century (PDF). Paris, UNESCO. pp. 129–131. ISBN 978-92-3-100138-3.

- Butcher, N. 2011. A Basic Guide to Open Educational Resources. Vancouver, BC, Commonwealth of Learning, and Paris, UNESCO.

- UNESCO, Chakroun, Borhene, Keevy, James (2018). "Digital credentialing: implications for the recognition of learning across borders" (PDF). UNESCO.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- AACRAO. 2014. Groningen Declaration. The Future of Digital Student Data Portability. Defining the Digital Student Data Ecosystem. Third annual meeting of the GDN. Washington DC, AACRO

- Mozilla Foundation and Peer 2 Peer University. 2012. Open badges for lifelong learning. Exploring an open badge ecosystem to support skill development and lifelong learning for real results such as jobs and advancement. Developed in collaboration with the MacArthur Foundation. Working document.

- Bjornavold, J. 2001. Making learning visible: identi cation, assessment and recognition of non-formal learning. European Journal of Vocational Training, Vol. 22, pp. 24–32.

- CEDEFOP. 2009. European Guidelines for Validating Non-Formal and Informal Learning. Luxembourg, CEDEFOP.

- CEDEFOP. 2014. Use of Validation by Enterprises for Human Resources and Career Development Purposes. Luxembourg, CEDEFOP.

- Mozilla website www.openbadges.org, accessed 19 April 2014.