Nikolai Ge

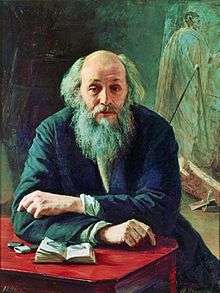

Nikolai Nikolaevich Ge (from his French ancestral surname "De Gay") (Ukrainian: Микола Миколайович Ґе; Russian: Николай Николаевич Ге; 27 February [O.S. 15 February] 1831 – 13 June [O.S. 1 June] 1894) was a Ukrainian-Russian realist painter and an early Ukrainian-Russian symbolist. He was famous for his works on historical and religious subjects.

Nikolai Ge | |

|---|---|

Николай Николаевич Ге | |

| |

| Born | 27 February [O.S. 15 February] 1831 |

| Died | 13 June [O.S. 1 June] 1894 (aged 63) Chernigov Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Nationality | |

| Education | Professor by rank (1864) |

| Alma mater | Imperial Academy of Arts (1857)[1] |

| Known for | Painting |

| Style | Symbolism, history painting |

| Movement | Russian symbolism, Peredvizhniki |

| Awards | |

Early life

Nikolai Ge was born in Voronezh at Ivanovsky khutor (now the Shevchenkovo village) to a Russian noble family of French origin. His grandfather who was a French nobleman immigrated to the Russian Empire during the 18th century and married a Russian woman. Ge's mother died when he was three months old.[2]

Ge grew up on his family estate in Popelukhy near Mohyliv-Podilskyi in Podilia.[3] His grandmother and a serf nurse cared for him.[4]

He graduated from the first Kyiv Gymnasium No. 1 where Mykola Kostomarov was one of his teachers. Then he studied physics and mathematics at Kyiv University and Saint Petersburg University.[3]

Career

In 1850, Ge gave up his career in science and enrolled in the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg. He studied under master painter Pyotr Basin. In 1857, he graduated from the Academy where he received a gold medal for The Witch of Endor Invoking the Spirit of the Prophet Samuel. According to Ge, during that period he was strongly influenced by Karl Briullov.

The gold medal secured a scholarship for Ge to study abroad. He visited Germany, Switzerland and France. In 1860 he settled in Italy where he met Alexander Andreyevich Ivanov in Rome. The Russian artist became a strong influence to Ge's future works.

In 1861, Ge painted The Last Supper using a photograph of Aleksandr Ivanovich Herzen as an image for his central figure of Christ. The photograph was taken by Herzen's cousin, Russian photographer Sergei Lvovich Levitsky.

Ge recounted, "I wanted to go to London to paint Alexander Herzen |Herzen's portrait [...] and he responded to my request with a large portrait by Mr. Levitsky." The final painting's similarity between the pose of Levitsky's photo of Herzen and Ge's pose of the painted Christ led the press of the day to hail the painting as "a triumph of materialism and nihilism."

This was the first known occasion where photography was used as the main source for a central character in a painting and speaks to the deep influences that photography would have later on in art and artistic movements like French Impressionism.

The painting (first purchased by Tsar Alexander II of Russia) made such a strong impression when it was shown in Saint Petersburg in 1863 that Ge was made a professor of Imperial Academy of Arts.[1]

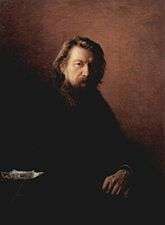

In 1864, Ge returned to Florence and painted Herzen's portrait along with the Messengers of the Resurrection and the first version of Christ on the Mount of Olives. The new paintings were not much of a success and the Imperial Academy refused to exhibit them in its annual exhibition.

In 1870, Ge again returned to Saint Petersburg where he turned to Russian history for subject matter. The painting Peter the Great Interrogates Tsarevich Alexey at Peterhof (1871) was a great success, but his other historical paintings were met with little to no interest. Ge wrote that a man should live off of farming and art should not be for sale. He bought a small khutor (farm) in Chernigov gubernia (currently Ukraine) and moved there. Ge became acquainted with Leo Tolstoy around this time and became a follower of his philosophy.

In the early 1880s, he returned to religious subjects and portraits. He claimed that everyone had the right to have a personal portrait and agreed to work for whatever commission the subject could afford. Among his later portrait subjects were Tolstoy, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin and the biblical Judas.

His later paintings on New Testament subjects were praised by liberal critics like Vladimir Stasov and criticized by conservatives for illustrating Ernest Renan rather than the New Testament and were banned forbidden by authorities for blasphemy. Quid Est Veritas? Christ and Pilate (1890) was also banned from an exhibition. The Judgment of the Sanhedrin: He is Guilty! (1892) was not admitted to the annual Academy of Arts exhibition; The Calvary (Golgotha) (1893) remained unfinished; The Crucifixion (1894) was banned by Tsar Alexander III.

Legacy

Ge died on his farm in 1894. The fate of many of his works remains a mystery. Ge had bequeathed all of his works to his Swiss benefactress, Beatrice de Vattville in exchange for a small stipend from her during his lifetime. When she died in 1952, none of Ge's works was found in her castle. Among the lost works is Ge's supposedly magnum opus painting The Crucifixion.

Ge's drawings were later discovered by art collectors in Swiss second-hand stores as late as 1974.[5] Many "were acquired by a young collector, Christoph Bolman [...] he had no idea of their origin, simply recognizing their value. Only some 15 years later, when he was visited during the Perestroika by Soviet acquaintances, did the attribution become clear. Negotiations for their acquisition and return to Russia – as a full collection, rather than sold off in parts – failed repeatedly during the 1990s. They were only concluded in 2011 after the Tretyakov Gallery was able to arrange sponsorship from a Russian state bank to purchase them for donation to the gallery's permanent collection."[6]

Selected works

Painting, 1852

Painting, 1852 The Judgment of the Sanhedrin - He is Guilty!

The Judgment of the Sanhedrin - He is Guilty! Peter the Great Interrogating the Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich at Peterhof, 1871

Peter the Great Interrogating the Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich at Peterhof, 1871 Conscience: Judas

Conscience: Judas Leo Tolstoy, 1882

Leo Tolstoy, 1882 Sophia Tolstaya (wife of Leo Tolstoy)

Sophia Tolstaya (wife of Leo Tolstoy) Portrait of Alexei Potechin

Portrait of Alexei Potechin

Study of John the Evangelist's head

Study of John the Evangelist's head Carrara marble

Carrara marble Maria, sister of Lazarus, meets Jesus who is going to their house

Maria, sister of Lazarus, meets Jesus who is going to their house Christ praying in Gethsemane (1888)

Christ praying in Gethsemane (1888)

See also

References

- Directory of the Imperial Academy of Arts 1915, p. 46.

- https://muzei-mira.com/biografia_hudojnikov/2856-nikolaj-nikolaevich-ge-biografija.html

- Stech, Marko Robert. "Ge, Mykola". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

- https://muzei-mira.com/biografia_hudojnikov/2856-nikolaj-nikolaevich-ge-biografija.html

- Николай Николаевич Ге: Из 'Библиологического словаря' священника Александра Меня [Nikolai Nikolaevich Ge: From the 'Bibliographical Dictionary' of the priest Alexander Men] (in Russian). Krotov.info. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- Birchenough, Tom (6 November 2011). "theartsdesk in Moscow: Nikolai Ge at the Tretyakov Gallery". Theartsdesk.com. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

Sources

- С. Н. Кондаков (1915). Юбилейный справочник Императорской Академии художеств. 1764-1914 (in Russian). 2. p. 46.

- "Nikolai Ge: A Chronicle of the Artist's Life and Work | The Tretyakov Gallery Magazine". www.tretyakovgallerymagazine.com. 2015-07-15. Retrieved 2018-05-30.

- Biography (in Russian)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nikolay Ge. |