Ney

The ney (Persian: نی / نای), is an end-blown flute that figures prominently in Middle Eastern music. In some of these musical traditions, it is the only wind instrument used. The ney has been played continually for 4,500–5,000 years, making it one of the oldest musical instruments still in use.

Persian ney with six holes (one on the back) | |

| Ancient | |

|---|---|

| Classification | End-blown |

| Playing range | |

| |

The Persian ney consists of a hollow cylinder with finger-holes. Sometimes a brass, horn, or plastic mouthpiece is placed at the top to protect the wood from damage, and to provide a sharper and more durable edge to blow at. The ney consists of a piece of hollow cane or giant reed with five or six finger holes and one thumb hole. Modern neys may be made instead of metal or plastic tubing. The pitch of the ney varies depending on the region and the finger arrangement. A highly skilled ney player, called neyzen, can reach more than three octaves, though it is more common to have several "helper" neys to cover different pitch ranges or to facilitate playing technically difficult passages in other dastgahs or maqams.

In Romanian, the word nai[1] is also applied to a curved pan flute while an end-blown flute resembling the Arab ney is referred to as caval.[2]

Typology

The typical Persian ney has six holes, one of which is on the back. Arabic and Turkish neys normally have seven holes, six in front and one thumb-hole in the back.

The interval between the holes is a semitone, although microtones (and broader pitch inflections) are achieved via partial hole-covering, changes of embouchure, or positioning and blowing angle.[3] Microtonal inflection is common and crucial to various traditions of taqsim (improvisation in the same scale before a piece is played).

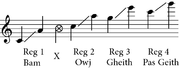

Neys are constructed in various keys. In the Arab system, there are seven common ranges: the longest and lowest-pitched is the Rast which is roughly equivalent to C in the Western equal temperament system, followed by the Dukah in D, the Busalik in E, the Jaharka in F, the Nawa in G, the Hussayni in A, and the Ajam in B (or B♭), with the Dukah Ney being the most common. Advanced players will typically own a set of several neys in various keys, although it is possible (albeit difficult) to play fully chromatically on any instrument. A slight exception to this rule is found in the extreme lowest range of the instrument, where the fingering becomes quite complex and the transition from the first octave (fundamental pitches) to the second is rather awkward.

Kargı Düdük

Gargy-tuyduk (Karghy tuiduk) this is a long reed flute whose origin, according to legend, is connected with Alexander of Macedonia, and a similar instrument existed in ancient Egypt. Kargı in Turkish means reed (Arundo donax, also known as Giant reed). The sound of the gargy-tuyduk has much in common with the two-voiced kargyra. During the playing of the gargy-tuyduk the melody is clearly heard, while the lower droning sound is barely audible. The allay epic songs have been described by the Turkologist N. Baskakov who divides them into three main types:

- a) Kutilep kayla, in which the second sound is a light drone.

- b) Sygyrtzip kayla, with a second whistling sound like the sound of a flute.

- c) Kargyrlap kayla, in which the second sound can be defined as hissing.[4] The sound of the Turkmen gargy-tuyduk is most like the Altay Kargyrkip kayla. The garg-tuyduk can have six finger holes and a length of 780 mm or five finger holes and a length of 550 mm. The range of the garg-tuyduk includes three registers:

- 1) The lowest register – "non-working" – is not used during the playing of a melody.

- 2) The same as on the "non-working" register but an octave higher.

- 3) High register from mi of the second octave to ti.

The Pamiri Nay

The Pamiri nay is a transverse flute made of wood or, in Eastern Badakhshan, eagle bone. Although the name is similar to the Arabic end-blown nay, it might well be that this side-blown flute is more related to Chinese flutes such as the dizi, perhaps through a Mongol link.[5] It is used for solo melodies as well as with orchestras and for vocal accompaniment. One of the main uses of the nay is for the most original form of the traditional performance ‘falaki’. These are brief melodic sessions which can express complaints against destiny, the injustice of heaven or exile to distant places, and sentiments such as the sorrow of a mother separated from her daughter, the sorrow of a lover torn from her/his beloved, etc.[6]

See also

- Turkish ney

- Tambin, a similar sounding flute used in West Africa.

- Tsuur / Choor

- Kawala, a similar instrument used in Arabic music

- Persian traditional music

- Arabic Music

- Music of Iran

- Washint

- Dilli Ney

References

- nai in Dicţionarul explicativ al limbii române, Academia Română, Institutul de Lingvistică "Iorgu Iordan", Editura Univers Enciclopedic, 1998.

- caval in Dicţionarul explicativ al limbii române, Academia Română, Institutul de Lingvistică "Iorgu Iordan", Editura Univers Enciclopedic, 1998.

- Satilmis Yayla. "Fingering of two popular scales on two common Turkish ney types". fromnorway.net. Archived from the original on 2016-04-12. Retrieved 2015-09-08.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- N. Baskakov, Altay folklore and literature Gorno-Altaysk, 1948, p.II

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-21. Retrieved 2011-05-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-07-06. Retrieved 2010-06-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Bibliography

- Effat, Mahmoud (2005). Beginner's Guide to the Nay. Translated by Jon Friesen; originally published in Arabic in 1968. Pitchphork Music. ISBN 0-9770192-0-9.

- Marwan Hassan (2010). Kawala & Nay: Die Ur-Flöten der Menschheit: Bauen, stimmen, pflegen und spielen. [German: explaining how to build and play the Kawala, Saluang, or Ghab and Ney-Flute]

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ney. |

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- About Persian Ney

.jpg)