Newly industrialized country

The category of newly industrialized country (NIC) is a socioeconomic classification applied to several countries around the world by political scientists and economists. They represent a subset of developing countries whose economic growth is much higher than other developing countries; and where the social consequences of industrialization, such as urbanization, are reorganizing society.

Definition

NICs are countries whose economies have not yet reached a developed country's status but have, in a macroeconomic sense, outpaced their developing counterparts. Such countries are still considered developing nations and only differ from other developing nations in the rate at which an NIC's growth is much higher over a shorter allotted time period compared to other developing nations.[1][2] Another characterization of NICs is that of countries undergoing rapid economic growth (usually export-oriented). Incipient or ongoing industrialization is an important indicator of an NIC. In many NICs, social upheaval can occur as primarily rural, or agricultural, populations migrate to the cities, where the growth of manufacturing concerns and factories can draw many thousands of laborers. NIC's introduce many new immigrants looking to improve their social and or political status through newly formed democracies and the increase in wages that most individuals who partake in such changes would obtain- [3]

Characteristics of newly industrialized countries

Newly industrialized countries can bring about an increase of stabilization in a country's social and economic status, allowing the people living in these nations to begin to experience better living conditions and better lifestyles. Another characteristic that appears in newly industrialized countries is the further development in government structures, such as democracy, the rule of law, and less corruption. Other such examples of a better lifestyle people living in such countries can experience are better transportation, electricity, and better access to water, compared to other developing countries.

Historical context

The term came into use around 1970, when the Four Asian Tigers[4] of Taiwan,[5][6][7][8] Singapore, Hong Kong and South Korea rose to global dominance in science, technological innovation and economic prosperity as well as NICs in the 1970s and 1980s, with exceptionally fast industrial growth since the 1960s; all four countries having since graduated into high-tech industrialized developed countries with wealthy high-income economies. There is a clear distinction between these countries and the countries now considered NICs. In particular, the combination of an open political process, high GNI per capita, and a thriving, export-oriented economic policy has shown that these East Asian economic tiger countries have now not only reached but surpassed the technological development of the developed countries in Western Europe, Canada, Japan, Australia, New Zealand and the United States.[5][6][7][8]

All four countries are classified as high-income economies by the World Bank and developed countries by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). All of the Four Asian Tigers, like Western European countries, have a Human Development Index considered "very high" by the United Nations.

Current

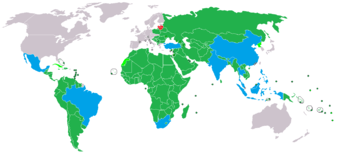

The table below presents the list of countries consistently considered NICs by different authors and experts.[9][10][11][12] Turkey and South Africa are classified as developed countries by the CIA.[13] Turkey was a founding member of the OECD in 1961 and Mexico joined in 1994. The G8+5 group is composed of the original G8 members in addition to China, India, Mexico, South Africa and Brazil.

Note: Green-colored cells indicate highest value or best performance in index, while yellow-colored cells indicate the opposite.

| Region | Country | GDP (Billions of USD, 2019 IMF)[14] | GDP per capita (USD, 2019 IMF)[15] |

GDP (PPP) (Billions of current Int$, 2019 IMF)[16] | GDP per capita (PPP) (current Int$, 2019 IMF)[17] |

Income inequality (GINI) 2011–17[18][19] | Human Development Index (HDI, 2018)[20] | Real GDP growth rate as of 2019[21] | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 358 | 6,100 | 809 | 13,753 | 63.0 (2014) | 0.705 (high) | 0.53 | [10][11][12] | |

| North America | 1,274 | 10,118 | 2,627 | 20,867 | 45.9 (2018) | 0.767 (high) | -0.28 | [9][10][11] | |

| South America | 1,847 | 8,796 | 3,456 | 16,461 | 53.9 (2018) | 0.761 (high) | 1.15 | [9][10][11] | |

| Asia | 14,140 | 10,098 | 27,308 | 19,503 | 38.5 (2016) | 0.758 (high) | 6.15 | [10][11] | |

| 2,935 | 2,171 | 11,325 | 8,378 | 37.8 (2011) | 0.647 (medium) | 4.85 | [10][11][12] | ||

| 1,111 | 4,163 | 3,737 | 13,998 | 39.0 (2018) | 0.707 (high) | 5.02 | [10][11][12] | ||

| 365 | 11,136 | 1,078 | 32,880 | 41.0 (2015) | 0.804 (very high) | 4.33 | [10][11][12] | ||

| 356 | 3,294 | 1,025 | 9,470 | 44.4 (2015) | 0.712 (high) | 5.95 | [9][10][11][12][22] | ||

| 529 | 7,792 | 1,383 | 20,364 | 36.4 (2018) | 0.765 (high) | 2.35 | [9][10][11][12] | ||

| Europe | 743 | 8,957 | 2,346 | 28,264 | 41.9 (2018) | 0.806 (very high) | 0.75 | [10][11][12] |

For China and India, the immense population of these two countries (each with over 1.2 billion people as of September 2015) means that per capita income will remain low even if either economy surpasses that of the United States in overall GDP. When GDP per capita is calculated according to purchasing power parity (PPP), this takes into account the lower costs of living in each newly industrialized country. GDP per capita typically is an indicator for living standards in a given country as well.[23]

Brazil, China, India, Mexico and South Africa meet annually with the G8 countries to discuss financial topics and climate change, due to their economic importance in today's global market and environmental impact, in a group known as G8+5.[24] This group is expected to expand to G14 by adding Egypt alongside the five aforementioned countries.[25]

Criticism

NICs usually benefit from comparatively low wage costs, which translates into lower input prices for suppliers. As a result, it is often easier for producers in NICs to outperform and outproduce factories in developed countries, where the cost of living is higher, and trade unions and other organizations have more political sway. This comparative advantage is often criticized by advocates of the fair trade movement.

Critics of NICs argue economic freedom is not always associated with political freedom in countries such as China, pointing out that Internet censorship and human rights violations are common.[27] The case is diametrically opposite for India; while being a liberal democracy throughout after its independence, India has been widely criticized for its inefficient, bureaucratic governance and slow process of structural reform. Thus, while political freedom in China remains limited, the average Chinese citizen enjoys a much higher standard of living than his or her counterpart in India.[28]

Problems

South Africa faces an influx of immigrants from countries such as Zimbabwe, although many also come from Burundi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Eritrea, Nigeria, Ethiopia and Somalia.[29] While South Africa is considered wealthy on a wealth-per-capita basis, economic inequality is persistent and extreme poverty remains high in the region.[30]

Mexico's economic growth is hampered in some areas by an ongoing drug war.[31]

Other NICs face common problems such as widespread corruption and/or political instability as well as other circumstances that cause them to face the "middle income trap".

See also

- Emerging markets

- Science in newly industrialized countries

- Flying geese paradigm

- Developing country

- Developed country

- North–South divide

- Groupings

- BRICS

- G8+5

- G-20 major economies

- G20 developing nations

- BRIC / MINT / Next Eleven

- Emerging and growth-leading economies

- CIVETS

- VISTA

References

- "Chapter 10: Less-developed And Newly Industrializing Countries | Essentials of Comparative Politics, 4e : W. W. Norton StudySpace". www.wwnorton.com. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/wesp/wesp_current/2014wesp_country_classification.pdf

- https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2016/wp16207.pdf

- "Japan Newly Industrialized Economies - Flags, Maps, Economy, History, Climate, Natural Resources, Current Issues, International Agreements, Population, Social Statistics, Political System".

- "TSMC is about to become the world's most advanced chipmaker". The Economist. 2018-04-05. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- "Taiwan's TSMC Could Be About to Dethrone Intel". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- April 10, Jibu Elias; 2018; P.m, 3:11 (2018-04-10). "TSMC set to beat Intel to become the world's most advanced chipmaker". PCMag India. Retrieved 2019-10-15.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Adams, Sam (2016-08-29). "Taiwanese navy fires NUCLEAR MISSILE at fisherman during horrifying accident". mirror. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- Paweł Bożyk (2006). "Newly Industrialized Countries". Globalization and the Transformation of Foreign Economic Policy. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 164. ISBN 0-7546-4638-6.

- Mauro F. Guillén (2003). "Multinationals, Ideology, and Organized Labor". The Limits of Convergence. Princeton University Press. pp. 126 (Table 5.1). ISBN 0-691-11633-4.

- David Waugh (2000). "Manufacturing industries (chapter 19), World development (chapter 22)". Geography, An Integrated Approach (3rd ed.). Nelson Thornes Ltd. pp. 563, 576–579, 633, and 640. ISBN 0-17-444706-X.

- N. Gregory Mankiw (2007). Principles of Economics (4th ed.). ISBN 0-324-22472-9.

- "The World Factbook".

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- "GINI Index Data Table". World Bank. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- Note: The higher the figure, the higher the inequality.

- "Human Development Report 2019 – "Human Development Indices and Indicators"" (PDF). HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. pp. 22–25. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- https://cnnphilippines.com/news/2019/12/10/undp-human-development-index-2019-philippines.html

- "How Do We Measure Standard of Living?" (PDF). The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

- G8 Structure and activities

- "France invites Egypt to join G14"

- John Broman (1996). Popular Development: Rethinking the Theory and Practice of Development. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 81. ISBN 1-557-86316-4.

- China Human Rights | Amnesty International USA. Amnestyusa.org (2013-02-08). Retrieved on 2013-07-28.

- Meredith, R (2008) The Elephant and the Dragon: The Rise of India and China and What it Means for All of Us, W. W Norton and Company ISBN 978-0-393-33193-6

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "UNHCR Global Appeal 2011 (update) - South Africa". UNHCR.

- Sedghi, Ami; Anderson, Mark (31 July 2015). "Africa wealth report 2015: rich get richer even as poverty and inequality deepen". The Guardian.

- Drug Trafficking, Violence and Mexico's Economic Future - Knowledge@Wharton. Knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu. Retrieved on 2013-07-28.