Natufian culture

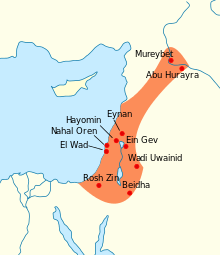

The Natufian culture (/nəˈtuːfiən/[1]) is a Late Epipaleolithic archaeological culture that existed from around 12,000 to 9,500 BC[2][3] or 13,050 to 7,550 BC[4] in the Levant. The culture was unusual in that it supported a sedentary or semi-sedentary population even before the introduction of agriculture. The Natufian communities may be the ancestors of the builders of the first Neolithic settlements of the region, which may have been the earliest in the world. Natufians founded a settlement where Jericho is today, which may therefore be the longest continuously inhabited urban area on Earth. Some evidence suggests deliberate cultivation of cereals, specifically rye, by the Natufian culture, at Tell Abu Hureyra, the site of earliest evidence of agriculture in the world.[5] The world's oldest evidence of bread-making has been found at Shubayqa 1, a 14,500-year-old site in Jordan's northeastern desert.[6] In addition, the oldest known evidence of beer, dating to approximately 13,000 BP, was found at the Raqefet Cave in Mount Carmel near Haifa in Israel.[7][8]

| |

| Geographical range | Levant |

|---|---|

| Period | Epipaleolithic |

| Dates | c. 13,050 – 7,550 BC or c. 12,000 – 9,500 BC |

| Type site | Shuqba cave (Wadi an-Natuf) |

| Major sites | Shuqba cave, Ain Mallaha, Ein Gev, Tell Abu Hureyra |

| Preceded by | Kebaran, Mushabian |

| Followed by | Neolithic: Khiamian, Shepherd Neolithic |

Generally, though, Natufians exploited wild cereals. Animals hunted included gazelles.[9] According to Christy G. Turner II, there is archaeological and physical anthropological evidence for a relationship between the modern Semitic-speaking populations of the Levant and the Natufians.[10] Archaeogenetics have revealed derivation of later (Neolithic to Bronze Age) Levantines primarily from Natufians, besides substantial admixture from Chalcholithic Anatolians.[11]

Dorothy Garrod coined the term Natufian based on her excavations at Shuqba cave (Wadi an-Natuf) in the western Judean Mountains.

Discovery

_1928_Natufian_culture_discovery.jpg)

The Natufian culture was discovered by British archaeologist Dorothy Garrod during her excavations of Shuqba cave in the Judaean Hills in the West Bank of the Jordan River.[12][13] Prior to the 1930s, the majority of archaeological work taking place in British Palestine was biblical archaeology focused on historic periods, and little was known about the region's prehistory. In 1928, Garrod was invited by the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem (BSAJ) to excavate Shuqba cave, where prehistoric stone tools had been discovered by a French priest named Alexis Mallon four years earlier. She discovered a layer sandwiched between the Upper Palaeolithic and Bronze Age deposits characterised by the presence of microliths. She identified this with the Mesolithic, a transitional period between the Palaeolithic and the Neolithic which was well-represented in Europe but had not yet been found in the Near East. A year later, when she discovered similar material at el-Wad Terrace, Garrod suggested the name "the Natufian culture", after Wadi an-Natuf that ran close to Shuqba. Over the next two decades Garrod found Natufian material at several of her pioneering excavations in the Mount Carmel region, including el-Wad, Kebara and Tabun, as did the French archaeologist René Neuville, firmly establishing the Natufian culture in the regional prehistoric chronology. As early as 1931, both Garrod and Neuville drew attention to the presence of stone sickles in Natufian assemblages and the possibility that this represented a very early agriculture.[13]

Dating

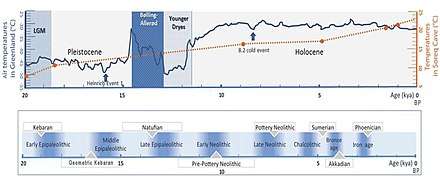

Radiocarbon dating places the Natufian culture at an epoch from the terminal Pleistocene to the very beginning of the Holocene, a time period between 12,500 and 9,500 BC.[15]

The period is commonly split into two subperiods: Early Natufian (12,000–10,800 BC) and Late Natufian (10,800–9,500 BC). The Late Natufian most likely occurred in tandem with the Younger Dryas (10,800 to 9,500 BC). The Levant hosts more than a hundred kinds of cereals, fruits, nuts, and other edible parts of plants, and the flora of the Levant during the Natufian period was not the dry, barren, and thorny landscape of today, but rather woodland.[12]

Precursors and associated cultures

The Natufian developed in the same region as the earlier Kebaran industry. It is generally seen as a successor, which evolved out of elements within that preceding culture. There were also other industries in the region, such as the Mushabian culture of the Negev and Sinai, which are sometimes distinguished from the Kebaran or believed to have been involved in the evolution of the Natufian.

More generally there has been discussion of the similarities of these cultures with those found in coastal North Africa. Graeme Barker notes there are: "similarities in the respective archaeological records of the Natufian culture of the Levant and of contemporary foragers in coastal North Africa across the late Pleistocene and early Holocene boundary".[16] According to Isabelle De Groote and Louise Humphrey Natufians practiced the Iberomaurusian and Capsian custom of sometimes extracting their maxillary central incisors (upper front teeth).[17]

Ofer Bar-Yosef has argued that there are signs of influences coming from North Africa to the Levant, citing the microburin technique and "microlithic forms such as arched backed bladelets and La Mouillah points."[18] But recent research has shown that the presence of arched backed bladelets, La Mouillah points, and the use of the microburin technique was already apparent in the Nebekian industry of the Eastern Levant.[19] And Maher et al. state that, "Many technological nuances that have often been always highlighted as significant during the Natufian were already present during the Early and Middle EP [Epipalaeolithic] and do not, in most cases, represent a radical departure in knowledge, tradition, or behavior."[20]

Authors such as Christopher Ehret have built upon the little evidence available to develop scenarios of intensive usage of plants having built up first in North Africa, as a precursor to the development of true farming in the Fertile Crescent, but such suggestions are considered highly speculative until more North African archaeological evidence can be gathered.[21][22] In fact, Weiss et al. have shown that the earliest known intensive usage of plants was in the Levant 23,000 years ago at the Ohalo II site.[23][24][25]

Anthropologist C. Loring Brace (1993) cross-analysed the craniometric traits of Natufian specimens with those of various ancient and modern groups from the Near East, Africa and Europe. The Late Pleistocene Epipalaeolithic Natufian sample was described as problematic due to its small size (consisting of only three males and one female), as well as the lack of a comparative sample from the Natufians' putative descendants in the Neolithic Near East. Brace observed that the Natufian fossils lay between those of the Niger-Congo-speaking populations and the other samples, which he suggested may point to a Sub-Saharan influence in their constitution.[26] Subsequent ancient DNA analysis of Natufian skeletal remains by Lazaridis et al. (2016) found that the specimens instead were a mix of 50% Basal Eurasian ancestral component (see genetics) and 50% Western Eurasian Unknown Hunter Gatherer (UHG) population related to European Western Hunter-Gatherers.[27]

According to Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen, "It seems that certain preadaptive traits, developed already by the Kebaran and Geometric Kebaran populations within the Mediterranean park forest, played an important role in the emergence of the new socioeconomic system known as the Natufian culture."[28]

Settlements

Settlements occur in the woodland belt where oak and Pistacia species dominated. The underbrush of this open woodland was grass with high frequencies of grain. The high mountains of Lebanon and the Anti-Lebanon, the steppe areas of the Negev desert in Israel and Sinai, and the Syro-Arabian desert in the east were much less favoured for Natufian settlement, presumably due to both their lower carrying capacity and the company of other groups of foragers who exploited this region.[29]

The habitations of the Natufian were semi-subterranean, often with a dry-stone foundation. The superstructure was probably made of brushwood. No traces of mudbrick have been found, which became common in the following Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA). The round houses have a diameter between three and six meters, and they contain a central round or subrectangular fireplace. In Ain Mallaha traces of postholes have been identified. Villages can cover over 1,000 square meters. Smaller settlements have been interpreted by some researchers as camps. Traces of rebuilding in almost all excavated settlements seem to point to a frequent relocation, indicating a temporary abandonment of the settlement. Settlements have been estimated to house 100–150 people, but there are three categories: small, medium, and large, ranging from 15 sq. m to 1,000 sq. m. There are no definite indications of storage facilities.

Material culture

Lithics

The Natufian had a microlithic industry centered on short blades and bladelets. The microburin technique was used. Geometric microliths include lunates, trapezes, and triangles. There are backed blades as well. A special type of retouch (Helwan retouch) is characteristic for the early Natufian. In the late Natufian, the Harif-point, a typical arrowhead made from a regular blade, became common in the Negev. Some scholars use it to define a separate culture, the Harifian.

Sickle blades also appear for the first time in the Natufian lithic industry. The characteristic sickle-gloss shows that they were used to cut the silica-rich stems of cereals, indirectly suggesting the existence of incipient agriculture. Shaft straighteners made of ground stone indicate the practice of archery. There are heavy ground-stone bowl mortars as well.

Art

The Ain Sakhri lovers, a carved stone object held at the British Museum, is the oldest known depiction of a couple having sex. It was found in the Ain Sakhri cave in the Judean desert.[30]

Burials

Natufian grave goods are typically made of shell, teeth (of red deer), bones, and stone. There are pendants, bracelets, necklaces, earrings, and belt-ornaments as well.

In 2008, the 12,400–12,000 cal BC grave of an apparently significant Natufian female was discovered in a ceremonial pit in the Hilazon Tachtit cave in northern Israel.[31] Media reports referred to this person as a shaman.[32] The burial contained the remains of at least three aurochs and 86 tortoises, all of which are thought to have been brought to the site during a funeral feast. The body was surrounded by tortoise shells, the pelvis of a leopard, forearm of a wild boar, wingtip of a golden eagle, and skull of a stone marten.[33][34]

Long-distance exchange

At Ain Mallaha (in Northern Israel), Anatolian obsidian and shellfish from the Nile valley have been found. The source of malachite beads is still unknown. Epipaleolithic Natufians carried parthenocarpic figs from Africa to the southeastern corner of the Fertile Crescent, c. 10,000 BC.[35]

Other finds

There was a rich bone industry, including harpoons and fish hooks. Stone and bone were worked into pendants and other ornaments. There are a few human figurines made of limestone (El-Wad, Ain Mallaha, Ain Sakhri), but the favorite subject of representative art seems to have been animals. Ostrich-shell containers have been found in the Negev.

In 2018, the world's oldest brewery was found, with the residue of 13,000-year-old beer, in a prehistoric cave near Haifa in Israel when researchers were looking for clues into what plant foods the Natufian people were eating. This is 8,000 years earlier than experts previously thought beer was invented.[36]

A study published in 2019 shows an advanced knowledge of lime plaster production at a Natufian cemetery in Nahal Ein Gev II site in the Upper Jordan Valley dated to 12 thousand (calibrated) years before present [k cal BP]. Production of plaster of this quality was previously thought to have been achieved some 2,000 years later.[37]

Subsistence

The Natufian people lived by hunting and gathering. The preservation of plant remains is poor because of the soil conditions, but wild cereals, legumes, almonds, acorns and pistachios may have been collected. Animal bones show that gazelle (Gazella gazella and Gazella subgutturosa) were the main prey. Additionally deer, aurochs and wild boar were hunted in the steppe zone, as well as onagers and caprids (ibex). Water fowl and freshwater fish formed part of the diet in the Jordan River valley. Animal bones from Salibiya I (12,300 – 10,800 cal BP) have been interpreted as evidence for communal hunts with nets, however, the radiocarbon dates are far too old compared to the cultural remains of this settlement, indicating contamination of the samples.[38]

Development of agriculture

A pita-like bread has been found from 12,500 BC attributed to Natufians. This bread is made of wild cereal seeds and papyrus cousin tubers, ground into flour.[39]

According to one theory,[32] it was a sudden change in climate, the Younger Dryas event (c. 10,800 to 9500 BC), which inspired the development of agriculture. The Younger Dryas was a 1,000-year-long interruption in the higher temperatures prevailing since the Last Glacial Maximum, which produced a sudden drought in the Levant. This would have endangered the wild cereals, which could no longer compete with dryland scrub, but upon which the population had become dependent to sustain a relatively large sedentary population. By artificially clearing scrub and planting seeds obtained from elsewhere, they began to practice agriculture. However, this theory of the origin of agriculture is controversial in the scientific community.[40]

Bovine-rib dagger, HaYonim Cave, Natufian Culture, 12,500–9500 BC

Bovine-rib dagger, HaYonim Cave, Natufian Culture, 12,500–9500 BC Stone mortars from Eynan, Natufian period, 12,500–9500 BC

Stone mortars from Eynan, Natufian period, 12,500–9500 BC Stone mortar from Eynan, Natufian period, 12,500–9500 BC

Stone mortar from Eynan, Natufian period, 12,500–9500 BC

Domesticated dog

Some of the earliest archaeological evidence for the domestication of the dog comes from Natufian sites. At the Natufian site of Ain Mallaha in Israel, dated to 12,000 BC, the remains of an elderly human and a four-to-five-month-old puppy were found buried together.[41] At another Natufian site at the cave of Hayonim, humans were found buried with two canids.[41]

Genetics

According to ancient DNA analyses conducted by Lazaridis et al. (2016) on Natufian skeletal remains from present-day northern Israel, the Natufians carried the Y-DNA (paternal) haplogroups E1b1b1b2(xE1b1b1b2a,E1b1b1b2b) (2/5; 40%), CT (2/5; 40%), and E1b1(xE1b1a1,E1b1b1b1) (1/5; 20%).[27][42] In terms of autosomal DNA, these Natufians carried around 50% of the Basal Eurasian (BE) and 50% of Western Eurasian Unknown Hunter Gather (UHG) components. However, they were slightly distinct from the northern Anatolian populations that contributed to the peopling of Europe, who had higher Western Hunter Gatherer (WHG) inferred ancestry. Natufians were strongly genetically differentiated[43] from Neolithic Iranian farmers from the Zagros Mountains, who were a mix of Basal Eurasians (up to 62%) and Ancient North Eurasians (ANE). This might suggest that different strains of Basal Eurasians contributed to Natufians and Zagros farmers,[44][45][46] as both Natufians and Zagros farmers descended from different populations of local hunter gatherers. Contact between Natufians, other Neolithic Levantines, Caucasus Hunter Gatherers (CHG), Anatolian and Iranian farmers is believed to have decreased genetic variability among later populations in the Middle East. The scientists suggest that the Levantine early farmers may have spread southward into East Africa, bringing along Western Eurasian and Basal Eurasian ancestral components separate from that which would arrive later in North Africa. According to their results, the Natufians shared no genetic affinity to present-day sub-Saharan Africans. However the scientists state that they were unable to test for affinity in the Natufians to early North African populations using present-day North Africans as a reference because present-day North Africans owe most of their ancestry to back-migration from Eurasia.[27][47]

Ancient DNA analysis has confirmed ancestral ties between the Natufian culture bearers and the makers of the Epipaleolithic Iberomaurusian culture of the Maghreb,[48] the Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture of the Levant,[48] the Early Neolithic Ifri n'Amr or Moussa culture of the Maghreb,[49] the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic culture of East Africa,[50] the Late Neolithic Kelif el Boroud culture of the Maghreb,[49] and the Ancient Egyptian culture of the Nile Valley,[51] with fossils associated with these early cultures all sharing a common genomic component.[49]

A 2018 analysis of autosomal DNA using modern populations as a reference, found the Natufians to have a predominant mixture of ancestral components from Western Eurasia and North Africa as well as a small (ca 6.8%) East African-related ancestry (showing affinities to the Omotic peoples of southern Ethiopia). It is suggested that this East African component may have been associated with the spread of Y-haplogroup E (particularly Y-haplogroup E-M215, also known as "E1b1b") lineages to Western Eurasia. [52]

Language

While the period involved makes it difficult to speculate on any language associated with the Natufian culture, linguists who believe it is possible to speculate this far back in time have written on this subject. As with other Natufian subjects, opinions tend to either emphasize North African connections or Asian connections. The view that the Natufians spoke an Afro-Asiatic language is accepted by Vitaly Shevoroshkin.[53] Alexander Militarev and others have argued that the Natufian may represent the culture that spoke the proto-Afroasiatic language,[54] which he in turn believes has a Eurasian origin associated with the concept of Nostratic languages. The possibility of Natufians speaking proto-Afro-Asiatic, and that the language was introduced into Africa from the Levant, is approved by Colin Renfrew with caution, as a possible hypothesis for proto-Afro-Asiatic dispersal.[55]

Some scholars, for example Christopher Ehret, Roger Blench and others, contend that the Afroasiatic Urheimat is to be found in North Africa or Northeast Africa, probably in the area of Egypt, the Sahara, Horn of Africa or Sudan.[56][57][58][59][60] Within this group, Ehret, who like Militarev believes Afroasiatic may already have been in existence in the Natufian period, would associate Natufians only with the Near Eastern pre-proto-Semitic branch of Afroasiatic.

Sites

| The Mesolithic |

|---|

| ↑ Upper Paleolithic |

|

| ↓ Neolithic |

| The Paleolithic |

|---|

| ↑ Pliocene (before Homo) |

|

|

|

|

Fertile Crescent:

|

| ↓ Mesolithic |

The Natufian culture has been documented at dozens of sites. Around 90 have been excavated, including:[61]

- Aammiq 2

- Tell Abu Hureyra

- Abu Salem

- Abu Usba

- Ain Choaab

- Ain Mallaha (Eynan)

- Ain Rahub

- Ain Sakhri

- Ala Safat

- Antelias Cave

- Azraq 18 (Ain Saratan)

- Baaz

- Bawwab al Ghazal

- Beidha

- Dederiyeh

- Dibsi Faraj

- El Khiam

- El Kowm I

- El Wad

- Erq el Ahmar

- Fazael IV & VI

- Gilgal II

- Givat Hayil I

- Har Harif K7

- Hatoula

- Hayonim Cave and Hayonim Terrace

- Hilazon Tachtit

- Hof Shahaf

- Huzuq Musa

- Iraq ed Dubb

- Iraq el Barud

- Iraq ez Zigan

- J202

- J203

- J406a

- J614

- Jayroud 1–3 & 9

- Jebel Saaidé II

- Jeftelik

- Jericho

- Kaus Kozah

- Kebara

- Kefar Vitkin 3

- Khallat Anaza (BDS 1407)

- Khirbat Janba

- Kosak Shamali

- Maaleh Ramon East

- Maaleh Ramon West

- Moghr el Ahwal

- Mureybet

- Mushabi IV & XIX

- Nachcharini Cave

- Nahal Ein Gev II

- Nahal Hadera I and Nahal Hadera IV (Hefsibah)

- Nahal Oren

- Nahal Sekher 23

- Nahal Sekher VI

- Nahr el Homr 2

- Qarassa 3

- Ramat Harif (G8)

- Raqefet Cave

- Rosh Horesha

- Rosh Zin

- Sabra 1

- Saflulim

- Salibiya 1

- Salibiya 9

- Sands of Beirut

- Shluhat Harif

- Shubayqa 1

- Shubayqa 6

- Shukhbah Cave

- Shunera VI

- Shunera VII

- Tabaqa (WHS 895)

- Taibé

- TBAS 102

- TBAS 212

- Tor at Tariq (WHS 1065)

- Tugra I

- Upper Besor 6

- Wadi Hammeh 27

- Wadi Jilat 22

- Wadi Judayid (J2)

- Wadi Mataha

- Yabrud 3

- Yutil al Hasa (WHS 784)

See also

References

- "Natufian". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Edwards, Phillip C. (2012-11-23). Wadi Hammeh 27, an Early Natufian Settlement at Pella in Jordan. BRILL. p. 21. ISBN 978-9004236097.

- García-Puchol, Oreto; Salazar-García, Domingo C. (2017-07-01). Times of Neolithic Transition along the Western Mediterranean. Springer. p. 16. ISBN 9783319529394.

- Grosman, Leore; Munro, Natalie; Belfer-Cohen, Anna (2008-12-01). "A 12,000-year-old Shaman Burial from the Southern Levant (Israel)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (46): 17665–9. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10517665G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0806030105. PMC 2584673. PMID 18981412.

- Moore, Andrew M. T.; Hillman, Gordon C.; Legge, Anthony J. (2000), Village on the Euphrates: From Foraging to Farming at Abu Hureyra, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-510806-4

- "Prehistoric bake-off: Scientists discover oldest evidence of bread". BBC. 17 July 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- "'World's oldest brewery' found in cave in Israel, say researchers". British Broadcasting Corporation. 15 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "'13,000-year-old brewery discovered in Israel, the oldest in the world". The Times of Israel. 12 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Kottak, Conrad P. (2005), Window on Humanity: A Concise Introduction to Anthropology, Boston: McGraw-Hill, pp. 155–156, ISBN 978-0-07-289028-0

- John D. Bengtson (2008-12-03). In Hot Pursuit of Language in Prehistory: Essays in the four fields of anthropology. In honor of Harold Crane Fleming. p. 22. ISBN 9789027289858.

Since there is archaeological and physical anthropological reason to believe that the Natufians were related to modern Semitic-speaking peoples of the Levant, I suggest that some part, if not all of, the Afro-Asiatic family originated north of Africa porper. Since Natufian culture dates to ca. 10,000 to 12,000 years ago it is suggested that the age of the AfroAsiaic language family might also be about that old.

- Lazaridis, Iosif; Nadel, Dani; Rollefson, Gary; Merrett, Deborah C.; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Fernandes, Daniel; Novak, Mario; Gamarra, Beatriz; Sirak, Kendra; Connell, Sarah; Stewardson, Kristin; Harney, Eadaoin; Fu, Qiaomei; Gonzalez-Fortes, Gloria; Jones, Eppie R.; Roodenberg, Songül Alpaslan; Lengyel, György; Bocquentin, Fanny; Gasparian, Boris; Monge, Janet M.; Gregg, Michael; Eshed, Vered; Mizrahi, Ahuva-Sivan; Meiklejohn, Christopher; Gerritsen, Fokke; Bejenaru, Luminita; Blüher, Matthias; Campbell, Archie; Cavalleri, Gianpiero; Comas, David; Froguel, Philippe; Gilbert, Edmund; Kerr, Shona M.; Kovacs, Peter; Krause, Johannes; McGettigan, Darren; Merrigan, Michael; Merriwether, D. Andrew; O'Reilly, Seamus; Richards, Martin B.; Semino, Ornella; Shamoon-Pour, Michel; Stefanescu, Gheorghe; Stumvoll, Michael; Tönjes, Anke; Torroni, Antonio; Wilson, James F.; Yengo, Loic; Hovhannisyan, Nelli A.; Patterson, Nick; Pinhasi, Ron; Reich, David (2016). "Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East" (PDF). Nature. 536 (7617): 419–424. Bibcode:2016Natur.536..419L. doi:10.1038/nature19310. PMC 5003663. PMID 27459054. Fig. 4. "Our data document continuity across the transition between hunter– gatherers and farmers, separately in the southern Levant and in the southern Caucasus–Iran highlands. The qualitative evidence for this is that PCA, ADMIXTURE, and outgroup f3 analysis cluster Levantine hunter–gatherers (Natufians) with Levantine farmers, and Iranian and CHG with Iranian farmers (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Figs 1, 3). We confirm this in the Levant by showing that its early farmers share significantly more alleles with Natufians than with the early farmers of Iran" Epipaleolithic Natufians were substantially derived from the Basal Eurasian lineage. "We used qpAdm (ref. 7) to estimate Basal Eurasian ancestry in each Test population. We obtained the highest estimates in the earliest populations from both Iran (66±13% in the likely Mesolithic sample, 48±6% in Neolithic samples), and the Levant (44±8% in Epipalaeolithic Natufians) (Fig. 2), showing that Basal Eurasian ancestry was widespread across the ancient Near East. [...] The idea of Natufians as a vector for the movement of Basal Eurasian ancestry into the Near East is also not supported by our data, as the Basal Eurasian ancestry in the Natufians (44±8%) is consistent with stemming from the same population as that in the Neolithic and Mesolithic populations of Iran, and is not greater than in those populations (Supplementary Information, section 4). Further insight into the origins and legacy of the Natufians could come from comparison to Natufians from additional sites, and to ancient DNA from North Africa."

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer (1998), "The Natufian Culture in the Levant, Threshold to the Origins of Agriculture" (PDF), Evolutionary Anthropology, 6 (5): 159–177, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6505(1998)6:5<159::AID-EVAN4>3.0.CO;2-7

- Boyd, Brian (1999). "'Twisting the kaleidoscope': Dorothy Garrod and the 'Natufian Culture'". In Davies, William; Charles, Ruth (eds.). Dorothy Garrod and the progress of the Palaeolithic. Oxford: Oxbow. pp. 209–223. ISBN 9781785705199.

- Zalloua, Pierre A.; Matisoo-Smith, Elizabeth (6 January 2017). "Mapping Post-Glacial expansions: The Peopling of Southwest Asia". Scientific Reports. 7: 40338. Bibcode:2017NatSR...740338P. doi:10.1038/srep40338. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5216412. PMID 28059138.

- Munro, Natalie D. (2003), "Small game, the Younger Dryas, and the transition to agriculture in the southern Levant" (PDF), Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte, 12: 47–71

- Barker G (2002) Transitions to farming and pastoralism in North Africa, in Bellwood P, Renfrew C (2002), Examining the Farming/Language Dispersal Hypothesis, pp 151–161.

- De Groote, Isabelle; Humphrey, Louise T. (2016-08-22). "Characterizing evulsion in the Later Stone Age Maghreb: Age, sex and effects on mastication" (PDF). Quaternary International. 413: 50–61. Bibcode:2016QuInt.413...50D. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.08.082. ISSN 1040-6182.

- Bar-Yosef O (1987) Pleistocene connections between Africa and SouthWest Asia: an archaeological perspective. The African Archaeological Review; Chapter 5, pg 29–38

- Richter, Tobias (2011). "Interaction before Agriculture: Exchanging Material and Sharing Knowledge in the Final Pleistocene Levant" (PDF). Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 21: 95–114. doi:10.1017/S0959774311000060.

- Maher, Tobias; Richter, Lisa A.; Stock, Jay T. (2012). "The Pre-Natufian Epipaleolithic: Long-Term Behavioral Trends in the Levant". Evolutionary Anthropology. 21 (2): 69–81. doi:10.1002/evan.21307. PMID 22499441.

- Ehret (2002) The Civilizations of Africa: A History to 1800. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia

- Bellwood P (2005) Blackwell, Oxford. Page 97

- Weiss, E; Kislev, ME; Simchoni, O; Nadel, D; Tschauner, H (2008). "Plant-food preparation area on an Upper Paleolithic brush hut floor at Ohalo II, Israel". Journal of Archaeological Science. 35 (8): 2400–2414. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.03.012.

- Nadel, D; Piperno, DR; Holst, I; Snir, A; Weiss, E (2012). "New evidence for the processing of wild cereal grains at Ohalo II, a 23 000-year-old campsite on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, Israel". Antiquity. 86 (334): 990–1003. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00048201.

- Weiss, Ehud; Wetterstrom, Wilma; Nadel, Dani; Bar-Yosef, Ofer (2004-06-29). "The broad spectrum revisited: Evidence from plant remains". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (26): 9551–9555. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.9551W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0402362101. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 470712. PMID 15210984.

- Brace, C. Loring; et al. (2006). "The questionable contribution of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age to European craniofacial form". PNAS. 103 (1): 242–247. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103..242B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509801102. PMC 1325007. PMID 16371462.

The Natufian sample from Israel is also problematic because it is so small, being constituted of three males and one female from the Late Pleistocene Epipalaeolithic (34) of Israel, and there was no usable Neolithic sample for the Near East... the small Natufian sample falls between the Niger-Congo group and the other samples used. Fig. 2 shows the plot produced by the first two canonical variates, but the same thing happens when canonical variates 1 and 3 (not shown here) are used. This placement suggests that there may have been a Sub-Saharan African element in the make-up of the Natufians (the putative ancestors of the subsequent Neolithic)

- Lazaridis, Iosif; et al. (17 June 2016). "The genetic structure of the world's first farmers". bioRxiv 10.1101/059311. – Table S6.1 – Y-chromosome haplogroups

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Belfer-Cohen, Anna (1989). "The Origins of Sedentism and Farming Communities in the Levant". Journal of World Prehistory. 3 (4): 447–498. doi:10.1007/bf00975111.

- Ofer Bar-Yosef, The Natufian culture and the Early Neolithic: Social and economic trends in Southwestern Asia, chapter 10 in Peter Bellwood and Colin Renfrew (eds.), Examining the Farming/Language Dispersal Hypothesis (2002), p.114.

- BBC. A History of the World. Ain Sakhri Lovers

- Grosman, L.; Munro, N. D.; Belfer-Cohen, A. (2008). "A 12,000-year-old Shaman burial from the southern Levant (Israel)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (46): 17665–17669. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10517665G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0806030105. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2584673. PMID 18981412.

- "Oldest Shaman Grave Found". National Geographic 04-Nov-2008

- "Hebrew U. unearths 12,000-year-old skeleton of 'petite' Natufian priestess". By Bradley Burston. Haaretz, 05-Nov-2008

- Hogenboom, Melissa (24 May 2016), Secrets of the world's oldest funeral feast, earth, BBC, retrieved 24 May 2016

- Kislev, ME; Hartmann, A; Bar-Yosef, O (2006). "Early domesticated fig in the Jordan Valley". Science. 312 (5778): 1372–1374. Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1372K. doi:10.1126/science.1125910. PMID 16741119.

- "'World's oldest brewery' found in a cave in Israel, say researchers". BBC. 15 September 2018.

- Friesem, David E.; Abadi, Itay; Shaham, Dana; Grosman, Leore (30 September 2019). "'Lime plaster covering burials 12,000 years ago presents a technological leap forward at the end of the Palaeolithic". Cambridge University Press. 1. doi:10.1017/ehs.2019.9.

- Mithen, Steven (2006). After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20,000–5000 BC. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674019997.

- "World's oldest bread found at prehistoric site in Jordan", The Jerusalem Post, 2018, retrieved 16 July 2018

- Balter, Michael (2010), "Archaeology: The Tangled Roots of Agriculture", Science, 327 (5964): 404–406, doi:10.1126/science.327.5964.404, PMID 20093449

- Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1995), "Origins of the dog: domestication and early history", in Serpell, James (ed.), The domestic dog: its evolution, behaviour and interactions with people, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-41529-3

- Lazaridis, Iosif et al. Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East, Nature 536, 419–424, 2016. Supplementary Table 1.

- Lazaridis, I; Nadel, D; Rollefson, G; Merrett, DC; Rohland, N; Mallick, S; Fernandes, D; Novak, M; Gamarra, B (2016). "Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East". Nature. 536 (7617): 419–424. Bibcode:2016Natur.536..419L. doi:10.1038/nature19310. PMC 5003663. PMID 27459054.

- Broushaki, F; Thomas, MG; Link, V; López, S; van Dorp, L; Kirsanow, K; Hofmanová, Z; Diekmann, Y; Cassidy, LM; Díez-del-Molino, D; Kousathanas, A; Sell, C; Robson, HK; Martiniano, R; Blöcher, J; Scheu, A; Kreutzer, S; Bollongino, R; Bobo, D; Davoudi, H; Munoz, O; Currat, M; Abdi, K; Biglari, F; Craig, OE; Bradley, DG; Shennan, S; Veeramah, KR; Mashkour, M; Wegmann, D; Hellenthal, G; Burger, J (2016). "Early Neolithic genomes from the eastern Fertile Crescent". Science. 353 (6298): 499–503. Bibcode:2016Sci...353..499B. doi:10.1126/science.aaf7943. PMC 5113750. PMID 27417496.

- Gallego-Llorente, M; Connell, S; Jones, ER; Merrett, DC; Jeon, Y; Eriksson, A; Siska, V; Gamba, C; Meiklejohn, C; Beyer, R; Jeon, S; Cho, YS; Hofreiter, M; Bhak, J; Manica, A; Pinhasi, R (2016). "The genetics of an early Neolithic pastoralist from the Zagros, Iran". Sci Rep. 6: 31326. Bibcode:2016NatSR...631326G. doi:10.1038/srep31326. PMC 4977546. PMID 27502179.

- Fernández, E; Pérez-Pérez, A; Gamba, C; Prats, E; Cuesta, P; Anfruns, J; Molist, M; Arroyo-Pardo, E; Turbón, D (2014). "Ancient DNA analysis of 8000 B.C. near eastern farmers supports an early neolithic pioneer maritime colonization of Mainland Europe through Cyprus and the Aegean Islands". PLOS Genet. 10 (6): e1004401. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004401. PMC 4046922. PMID 24901650.

- https://www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2016/06/16/059311.full.pdf (Quote:”However, no affinity of Natufians to sub-Saharan Africans is evident in our genome-wide analysis, as present-day sub-Saharan Africans do not share more alleles with Natufians than with other ancient Eurasians (Extended Data Table 1).”)

- van de Loosdrecht et al. (2018-03-15). "Pleistocene North African genomes link Near Eastern and sub-Saharan African human populations". Science. 360 (6388): 548–552. Bibcode:2018Sci...360..548V. doi:10.1126/science.aar8380. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 29545507.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Fregel; et al. (2018). "Ancient genomes from North Africa evidence prehistoric migrations to the Maghreb from both the Levant and Europe" (PDF). bioRxiv 10.1101/191569.

- Skoglund; et al. (September 21, 2017). "Reconstructing Prehistoric African Population Structure". Cell. 171 (1): 59–71. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.049. PMC 5679310. PMID 28938123.

- Schuenemann, Verena J.; et al. (2017). "Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods". Nature Communications. 8: 15694. Bibcode:2017NatCo...815694S. doi:10.1038/ncomms15694. PMC 5459999. PMID 28556824.

- Shriner D (2018). "Re-analysis of Whole Genome Sequence Data From 279 Ancient Eurasians Reveals Substantial Ancestral Heterogeneity". Frontiers in Genetics. 9: 268. doi:10.3389/fgene.2018.00268. PMC 6062619. PMID 30079081.

- Winfried Nöth (1994). Origins of Semiosis: Sign Evolution in Nature and Culture. p. 293. ISBN 9783110877502.

- Roger Blench, Matthew Spriggs (2003). Archaeology and Language IV: Language Change and Cultural Transformation. p. 70. ISBN 9781134816231.

- John A. Hall, I. C. Jarvie (2005). Transition to Modernity: Essays on Power, Wealth and Belief. p. 27. ISBN 9780521022279.

- Blench R (2006) Archaeology, Language, and the African Past, Rowman Altamira, ISBN 0-7591-0466-2, ISBN 978-0-7591-0466-2, https://books.google.com/books?doi=esFy3Po57A8C

- Ehret, Christopher; Keita, S. O. Y.; Newman, Paul (2004). "The Origins of Afroasiatic". Science. 306 (5702): 1680.3–1680. doi:10.1126/science.306.5702.1680c. PMID 15576591.

- Bernal M (1987) Black Athena: the Afroasiatic roots of classical civilization, Rutgers University Press, ISBN 0-8135-3655-3, ISBN 978-0-8135-3655-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=yFLm_M_OdK4C

- Bender ML (1997), Upside Down Afrasian, Afrikanistische Arbeitspapiere 50, pp. 19–34

- Militarev A (2005) Once more about glottochronology and comparative method: the Omotic-Afrasian case, Аспекты компаративистики – 1 (Aspects of comparative linguistics – 1). FS S. Starostin. Orientalia et Classica II (Moscow), p. 339-408. http://starling.rinet.ru/Texts/fleming.pdf

- Arranz-Otaegui, Amaia; González Carretero, Lara; Roe, Joe; Richter, Tobias (2018). ""Founder crops" v. wild plants: Assessing the plant-based diet of the last hunter-gatherers in southwest Asia". Quaternary Science Reviews. 186: 263–283. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.02.011. ISSN 0277-3791.

Further reading

- Balter, Michael (2005), The Goddess and the Bull, New York: Free Press, ISBN 978-0-7432-4360-5

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer (1998), "The Natufian Culture in the Levant, Threshold to the Origins of Agriculture" (PDF), Evolutionary Anthropology, 6 (5): 159–177, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6505(1998)6:5<159::AID-EVAN4>3.0.CO;2-7

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Belfer-Cohen, Anna (1999). "Encoding information: unique Natufian objects from Hayonim Cave, Western Galilee, Israel". Antiquity. 73 (280): 402–409. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00088347.

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer (1992), Valla, Francois R. (ed.), The Natufian Culture in the Levant, Ann Arbor: International Monographs in Prehistory, ISBN 978-1-879621-03-9

- Campana, Douglas V.; Crabtree, Pam J. (1990). "Communal Hunting in the Natufian of the Southern Levant: The Social and Economic Implications". Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology. 3 (2): 223–243. doi:10.1558/jmea.v3i2.223.

- Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1999), A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals (2nd ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-63247-8

- Dubreuil, Laure (2004), "Long-term trends in Natufian subsistence: a use-wear analysis of ground stone tools", Journal of Archaeological Science, 31 (11): 1613–1629, doi:10.1016/j.jas.2004.04.003

- Munro, Natalie D. (August–October 2004). "Zooarchaeological measures of hunting pressure and occupation intensity in the Natufian: Implications for agricultural origins" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 45: S5–S33. doi:10.1086/422084.

- Simmons, Alan H. (2007), The Neolithic Revolution in the Near East: Transforming the Human Landscape, University of Arizona Press, ISBN 978-0816529667

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Natufian. |