National Party of Australia

The National Party of Australia, also known as The Nationals or The Nats, is an Australian political party. Traditionally representing graziers, farmers, and rural voters generally, it began as the Australian Country Party in 1920 at a federal level. It later adopted the name National Country Party in 1975, before taking its current name in 1982.

National Party of Australia | |

|---|---|

| President | Larry Anthony |

| Leader | Michael McCormack |

| Deputy leader | David Littleproud |

| Founded | 22 January 1920 (as Australian Country Party) |

| Headquarters | John McEwen House 7 National Circuit Barton, ACT 2600 |

| Youth wing | Young Nationals |

| Ideology | Conservatism Agrarianism |

| Political position | Centre-right |

| National affiliation | Liberal–National Coalition |

| Colours | Green and yellow |

| Slogan | For Regional Australia |

| House of Representatives | 15 / 151 [Note 1] |

| Senate | 5 / 76 [Note 2] |

| Website | |

| www | |

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Australia |

|---|

|

Related topics |

|

Federally, and in New South Wales, and to an extent in Victoria and historically in Western Australia, it has in government been the minor party in a centre-right Coalition with the Liberal Party of Australia, and its leader has usually served as Deputy Prime Minister. In Opposition the Coalition was usually maintained, but even otherwise the party still generally continued to work in co-operation with the Liberal Party of Australia (as had their predecessors the Nationalist Party of Australia and United Australia Party). In Queensland, however, the Country Party (later National Party) was the senior coalition party between 1925 and 2008, after which it merged in that state with the junior Liberal Party of Australia to form the Liberal National Party (LNP). Despite taking a conservative position politically, the National Party has long pursued agrarian socialist economic policies. Ensuring support for farmers, either through government grants and subsidies or through community appeals, is a major focus of National Party policy. The unusual hybrid of welfare and free market attitudes that characterise the party has led to it being often accused of seeking to privatise profits and socialise costs for the agricultural and mining sectors.

The current leader of the National Party is Michael McCormack, who won a leadership spill following Barnaby Joyce's resignation in February 2018.[1] The most recent deputy leader of the Nationals, from 7 December 2017 until her resignation due to acting with a conflict of interest on 2 February 2020, was Bridget McKenzie.

History

The Country Party was formally founded in 1913 in Western Australia, and nationally in 1920, from a number of state-based parties such as the Victorian Farmers' Union (VFU) and the Farmers and Settlers Party of New South Wales.[2] Australia's first Country Party was founded in 1912 by Harry J. Stephens, editor of The Farmer & Settler, but, under fierce opposition from rival newspapers,[3] failed to gain momentum.

The VFU won a seat in the House of Representatives at the Corangamite by-election held in December 1918, with the help of the newly introduced preferential voting system.[4] At the 1919 federal election the state-based Country Parties won federal seats in New South Wales, Victoria and Western Australia. They also began to win seats in state parliaments. In 1920 the Country Party was established as a national party led by William McWilliams from Tasmania. In his first speech as leader, McWilliams laid out the principles of the new party, stating "we crave no alliance, we spurn no support but we intend drastic action to secure closer attention to the needs of primary producers"[5] McWilliams was deposed as party leader in favour of Earle Page in April 1921, following instances where McWilliams voted against the party line. McWilliams later left the Country Party to sit as an Independent.[5]

According to historian B. D. Graham (1959), the graziers who operated the sheep stations were politically conservative. They disliked the Labor Party, which represented their workers, and feared that Labor governments would pass unfavorable legislation and listen to foreigners and communists. The graziers were satisfied with the marketing organisation of their industry, opposed any change in land tenure and labour relations, and advocated lower tariffs, low freight rates, and low taxes. On the other hand, Graham reports, the small farmers, not the graziers, founded the Country party. The farmers advocated government intervention in the market through price support schemes and marketing pools. The graziers often politically and financially supported the Country party, which in turn made the Country party more conservative.[6]

The Country Party's first election as a united party, in 1922, saw it in an unexpected position of power. It won enough seats to deny the Nationalists an overall majority. It soon became apparent that the price for Country support would be a full-fledged coalition with the Nationalists. However, Page let it be known that his party would not serve under Hughes, and forced his resignation. Page then entered negotiations with the Nationalists' new leader, Stanley Bruce, for a coalition government. Page wanted five seats for his Country Party in a Cabinet of 11, including the Treasurer portfolio and the second rank in the ministry for himself. These terms were unusually stiff for a prospective junior coalition partner in a Westminster system, and especially so for such a new party. Nonetheless, with no other politically realistic coalition partner available, Bruce readily agreed, and the "Bruce-Page Ministry" was formed. This began the tradition of the Country Party leader ranking second in Coalition cabinets.[2]

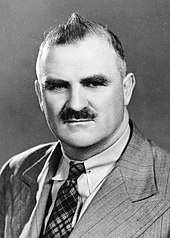

Page remained dominant in the party until 1939, and briefly served as caretaker Prime Minister between the death of Joseph Lyons and the election of Robert Menzies as his successor. However, Page gave up the leadership rather than serve under Menzies. The coalition was re-formed under Archie Cameron in 1940, and continued until October 1941 despite the election of Arthur Fadden as leader after the 1940 election. Fadden was well regarded within conservative circles and proved to be a loyal deputy to Menzies in the difficult circumstances of 1941. When Menzies was forced to resign as Prime Minister, the UAP was so bereft of leadership that Fadden briefly succeeded him (despite the Country Party being the junior partner in the governing coalition). However, the two independents who had been propping up the government rejected Fadden's budget and brought the government down.[7] Fadden stood down in favour of Labor leader John Curtin.

The Fadden-led Coalition made almost no headway against Curtin, and was severely defeated in the 1943 election. After that loss, Fadden became deputy Leader of the Opposition under Menzies, a role that continued after Menzies folded the UAP into the Liberal Party of Australia in 1944. Fadden remained a loyal partner of Menzies, though he was still keen to assert the independence of his party. Indeed, in the lead up to the 1949 federal election, Fadden played a key role in the defeat of the Chifley Labor government, frequently making inflammatory claims about the "socialist" nature of the Labor Party, which Menzies could then "clarify" or repudiate as he saw fit, thus appearing more "moderate". In 1949, Fadden became Treasurer in the second Menzies government and remained so until his retirement in 1958. His successful partnership with Menzies was one of the elements that sustained the coalition, which remained in office until 1972 (Menzies himself retired in 1966).[7]

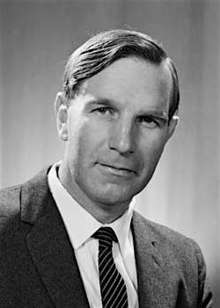

Fadden's successor, Trade Minister John McEwen, took the then unusual step of declining to serve as Treasurer, believing he could better ensure that the interests of Australian primary producers were safeguarded. Accordingly, McEwen personally supervised the signing of the first post-war trade treaty with Japan, new trade agreements with New Zealand and Britain, and Australia's first trade agreement with the USSR (1965). In addition to this, he insisted on developing an all-encompassing system of tariff protection that would encourage the development of those secondary industries that would "value add" Australia's primary produce. His success in this endeavour is sometimes dubbed "McEwenism". This was the period of the Country Party's greatest power, as was demonstrated in 1962 when McEwen was able to insist that Menzies sack a Liberal Minister who claimed that Britain's entry into the European Economic Community was unlikely to severely impact on the Australian economy as a whole.[8]

Menzies retired in 1966 and was succeeded by Harold Holt. McEwen thus became the longest-tenured member of the government, with the informal right to veto government policy. The most significant instance in which McEwen exercised this right came when Holt disappeared in December 1967. John Gorton became the new Liberal Prime Minister in January 1968. McEwen was sworn in as interim Prime Minister pending the election of the new Liberal leader. Logically, the Liberals' deputy leader, William McMahon, should have succeeded Holt. However, McMahon was a staunch free-trader, and there were also rumors that he was homosexual. As a result, McEwen told the Liberals that he and his party would not serve under McMahon. McMahon stood down in favour of John Gorton. It was only after McEwen announced his retirement that MacMahon was able to successfully challenge Gorton for the Liberal leadership. McEwen's reputation for political toughness led to him being nicknamed "Black Jack" by his allies and enemies alike.[9]

At the state level, from 1957 to 1989, the Country Party under Frank Nicklin and Joh Bjelke-Petersen dominated governments in Queensland—for the last six of those years ruling in its own right, without the Liberals. It also took part in governments in New South Wales, Victoria, and Western Australia.[10]

However, successive electoral redistributions after 1964 indicated that the Country Party was losing ground electorally to the Liberals as the rural population declined, and the nature of some parliamentary seats on the urban/rural fringe changed. A proposed merger with the Democratic Labor Party (DLP) under the banner of "National Alliance" was rejected when it failed to find favour with voters at the 1974 state election.

Also in 1974, the Northern Territory members of the party joined with its Liberal party members to form the independent Country Liberal Party. This party continues to represent both parent parties in that territory. A separate party, the Joh-inspired NT Nationals, competed in the 1987 election with former Chief Minister Ian Tuxworth winning his seat of Barkly by a small margin. However, this splinter group were not endorsed by the national executive and soon disappeared from the political scene.[11]

National Country Party and National Party

The National Party was confronted by the impact of demographic shifts from the 1970s: between 1971 and 1996, the population of Sydney and surrounds grew by 34%, with even larger growth in coastal New South Wales, while more remote rural areas grew by a mere 13%, further diminishing the National Party's base.[12] On 2 May 1975 at the federal convention in Canberra, the Country Party changed its name to the National Country Party of Australia as part of a strategy to expand into urban areas.[13][14] This had some success in Queensland under Joh Bjelke-Petersen, but nowhere else. The party briefly walked out of the coalition agreement in Western Australia in May 1975, returning within the month. However, the party split in two over the decision and other factors in late 1978, with a new National Party forming and becoming independent, holding three seats in the Western Australian lower house, while the National Country Party remained in coalition and also held three seats. They reconciled after the Burke Labor government came to power in 1983.

The 1980s were dominated by the feud between Bjelke-Petersen and the federal party leadership. Bjelke-Petersen briefly triumphed in 1987, forcing the Nationals to tear up the Coalition agreement and support his bid to become Prime Minister. The "Joh for Canberra" campaign backfired spectacularly when a large number of three-cornered contests allowed Labor to win a third term under Bob Hawke; however, in 1987 the National Party won a bump in votes and recorded its highest vote in more than four decades, but it also recorded a new low in the proportion of seats won.[15] The collapse of Joh for Canberra also proved to be the Queensland Nationals' last hurrah; Bjelke-Petersen was forced into retirement a few months after the federal election, and his party was heavily defeated in 1989. The federal National Party were badly defeated at the 1990 election, with leader Charles Blunt one of five MPs to lose his seat.[16][17]

Blunt's successor as leader, Tim Fischer, recovered two seats at the 1993 election, but lost an additional 1.2% of the vote from its 1990 result. In 1996, as the Coalition won a significant victory over the Keating Labor government, the National Party recovered another two seats, and Fischer became Deputy Prime Minister under John Howard.[18]

The Nationals experienced difficulties in the late 1990s from two fronts – firstly from the Liberal Party, who were winning seats on the basis that the Nationals were not seen to be a sufficiently separate party, and from the One Nation Party riding a swell of rural discontent with many of the policies such as multiculturalism and gun control embraced by all of the major parties. The rise of Labor in formerly safe National-held areas in rural Queensland, particularly on the coast, has been the biggest threat to the Queensland Nationals.

At the 1998 Federal election, the National Party recorded only 5.3% of the vote in the House of Representatives, its lowest ever, and won only 16 seats, at 10.8% its second lowest proportion of seats.[12]

The National Party under Fischer and his successor, John Anderson, rarely engaged in public disagreements with the Liberal Party, which weakened the party's ability to present a separate image to rural and regional Australia. In 2001 the National Party recorded its second-worst result at 5.6% winning 13 seats, and its third lowest at 5.9% at the 2004 election, winning only 12 seats.[12]

Australian psephologist Antony Green argues that two important trends have driven the National Party's decline at a federal level: "the importance of the rural sector to the health of the nation's economy" and "the growing chasm between the values and attitudes of rural and urban Australia". Green has suggested that the result has been that "Both have resulted in rural and regional voters demanding more of the National Party, at exactly the time when its political influence has declined. While the National Party has never been the sole representative of rural Australia, it is the only party that has attempted to paint itself as representing rural voters above all else",[12]

In June 2005 party leader John Anderson announced that he would resign from the ministry and as Leader of the Nationals due to a benign prostate condition, he was succeeded by Mark Vaile. At the following election the Nationals vote declined further, with the party winning a mere 5.4% of the vote and securing only 10 seats.[19]

In 2010, under the leadership of Warren Truss the party received its lowest vote to date, at only 3.4%, however they secured a slight increase in seats from 10 to 12. At the following election in 2010 the national Party's fortunes improved slightly with a vote of 4.2% and an increase in seats from 12 to 15.[19]

At the 2016 Double dissolution election, under the Leadership of Barnaby Joyce the party secured 4.6% of the vote and 16 seats. In 2018, reports emerged that the National Party leader and Deputy Prime Minister, Barnaby Joyce was expecting a child with his former communications staffer Vikki Campion. Joyce resigned after revelations that he had been engaged in an extramarital affair. Later in the same year it was revealed that the NSW National party and its youth wing, the Young Nationals had been infiltrated by neo-Nazis with more than 30 members being investigated for alleged links to neo-Nazism. Leader McCormack denounced the infiltration, and several suspected neo-Nazis were expelled from the party and its youth wing.[19][20][21]

At the 2019 Australian federal election, despite severe drought, perceived inaction over the plight of the Murray-Darling Basin, a poor performance in the New South Wales state election and sex scandals surrounding the member for Mallee, Andrew Broad and party leader Barnaby Joyce, the National Party saw only a small decline in vote, down 0.10% to attain 4.51% of the primary vote.[22]

State and territory parties

The official state and territorial party organisations (or equivalents) of the National Party are:[23]

- National Party of Australia – NSW

- Liberal National Party of Queensland

- National Party of Australia (SA)

- National Party of Australia – Tasmania

- National Party of Australia – Victoria

- National Party of Australia (WA)

- Country Liberal Party

The National Party does not have a branch in the Australian Capital Territory.

New South Wales

Queensland

Queensland is the only state in which the Nationals have consistently been the stronger coalition partner. The Nationals were the senior partner in the non-Labor Coalition from the 1950s until the Coalition was broken up in 1983 and at the following state election the Nationals (under Joh Bjelke-Petersen) came up one seat short of a majority at the election, but gained one a few weeks later after Don Lane and Brian Austin crossed the floor to join the Nationals. The Nationals subsequently governed in their own right until 1989.

The Queensland branch of the Country Party was the first to change its name to the National Party in April 1974.[24]

The continued success of the Australian Labor Party at a state level has put pressure on the Nationals' links with the Liberal Party, their traditional coalition partner. In most states, the Coalition agreement is not in force when the parties are in opposition, allowing the two parties greater freedom of action.

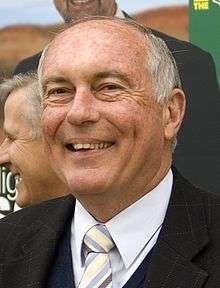

In Queensland the National Party merged with the Liberal Party to form the Liberal National Party (LNP) in 2008. The LNP led by Lawrence Springborg went on to lose the March 2009 election to Anna Bligh's Australian Labor Party. However, in the 2012 state election, the LNP defeated the Labor Party in a landslide, but lost government in the 2015 landslide to Labor, also losing in 2018.

South Australia

In South Australia, for the first time in the Nationals' history, in 2002 the single Nationals member in the House of Assembly entered the Rann Labor Government as a Minister forming an informal coalition between the two parties. Since the 2010 South Australian State election, the Nationals in South Australia have no representative in either the House of Assembly or the Upper House or at a Federal level. There existed a distinctly different Country Party in South Australia which merged with the Liberal Federation to become the Liberal and Country League in 1932.

Tasmania

The Nationals have had a very intermittent history of organising in Tasmania compared to the main states with limited electoral success. The most recent attempt began in 2013 but disagreements between the state and federal parties led to the latter cutting ties[25] and the state party renamed itself the Tasmania Party[26] before disappearing off the scene.[27] In May 2018 federal senator Steve Martin joined the party and declared he would seek to relaunch it in the state.[28] The Nationals contested Tasmanian seats (both houses) in the 2019 Australian federal election.

Victoria

The Nationals were stung in early 2006, when their only Victorian senator, Julian McGauran, defected to the Liberals and created a serious rift between the Nationals and the Liberals.[29] Several commentators believed that changing demographics and unfavourable preference deals would demolish the Nationals at the state election that year, but they went on to enjoy considerable success by winning two extra lower house seats. The Nationals were in a coalition government with the Liberals at a State level in Victoria until their defeat at the 2014 election. Following the election, the ABC reported that the coalition parties would "review" whether to continue their joint working arrangement into opposition.[30] However, both outgoing Nationals leader Peter Ryan and incoming Liberal leader Matthew Guy indicated they felt the coalition should continue.[31][32]

Western Australia

Western Australia's National Party chose to assert its independence after an acrimonious co-habitation with the Liberals on the 2005 campaign trail. Unlike its New South Wales and Queensland counterparts, the WA party had decided to oppose Liberal candidates in the 2008 election. The party aimed to hold the balance of power in the state "as an independent conservative party" ready to negotiate with the Liberals or Labor to form a minority government. After the election, the Nationals negotiated an agreement to form a government with the Liberals and an independent MP, though not described as a "traditional coalition" due to the reduced cabinet collective responsibility of National cabinet members.[33]

Western Australia's one-vote-one-value reforms will cut the number of rural seats in the state assembly to reflect the rural population level: this, coupled with the Liberals' strength in country areas has put the Nationals under significant pressure.

Australian Capital Territory

The Nationals have rarely organised or stood in the Australian Capital Territory. Federally their only candidatures were in the 1974 election when they contested both constituencies and secured 3.5% of the territory vote.[34] In the first election to the Legislative Assembly in 1989 David Adams, a former Liberal member of the old House of Assembly, headed a list of three candidates for the Nationals.[35] They received 1947 votes (1.37%) and did not get any members elected.[36] The party has not stood in the territory since.

Northern Territory

Political role

The Nationals see their main role as giving a voice to Australians who live outside the country's metropolitan areas.

Traditionally, the leader of the National Party serves as Deputy Prime Minister when the Coalition is in government. This tradition dates back to the creation of the office in 1968.

The National Party's support base and membership are closely associated with the agricultural community. Historically anti-union, the party has vacillated between state support for primary industries ("agrarian socialism") and free agricultural trade and has opposed tariff protection for Australia's manufacturing and service industries. This vacillation prompted those opposed to the policies of the Nationals to joke that its real aim was to "capitalise its gains and socialise its losses!". It is usually pro-mining, pro-development, and anti-environmentalist.

"Countrymindedness" was a slogan that summed up the ideology of the Country Party from 1920 through the early 1970s.[37] It was an ideology that was physiocratic, populist, and decentralist; it fostered rural solidarity and justified demands for government subsidies. "Countrymindedness" grew out of the failure of the country areas to participate in the rapid economic and population expansions that occurred after 1890. The growth of the ideology into urban areas came as most country people migrated to jobs in the cities. Its decline was due mainly to the reduction of real and psychological differences between country and city brought about by the postwar expansion of the Australian urban population and to the increased affluence and technological changes that accompanied it.[38][39]

The Nationals vote is in decline and its traditional supporters are turning instead to prominent independents such as Bob Katter, Tony Windsor and Peter Andren in Federal Parliament and similar independents in the Parliaments of New South Wales, Queensland and Victoria, many of whom are former members of the National Party. In fact since the 2004 Federal election, National Party candidates received fewer first preference votes than the Australian Greens.

Demographic changes are not helping, with fewer people living and employed on the land or in small towns, the continued growth of the larger provincial centres, and, in some cases, the arrival of left-leaning "city refugees" in rural areas. The Liberals have also gained support as the differences between the coalition partners on a federal level have become invisible. This was highlighted in January 2006, when Nationals Senator Julian McGauran defected to the Liberals, saying that there was "no longer any real distinguishing policy or philosophical difference".[40]

State Lower House Seats (Single Lib-Nat Party represents QLD; graphic represents seats held by a National aligned LNP MP) | |

|---|---|

| NSW Parliament | 13 / 93 |

| VIC Parliament | 6 / 88 |

| QLD Parliament | 25 / 93 |

| WA Parliament | 5 / 59 |

In Queensland, Nationals leader Lawrence Springborg advocated merger of the National and Liberal parties at a state level in order to present a more effective opposition to the Labor Party. Previously this plan had been dismissed by the Queensland branch of the Liberal party, but the idea received in-principle support from the Liberals. Federal leader Mark Vaile stated the Nationals will not merge with the Liberal Party at a federal level. The plan was opposed by key Queensland Senators Ron Boswell and Barnaby Joyce, and was scuttled in 2006. After suffering defeat in the 2006 Queensland poll, Lawrence Springborg was replaced by Jeff Seeney, who indicated he was not interested in merging with the Liberal Party until the issue is seriously raised at a Federal level.

In September 2008, Joyce replaced CLP Senator and Nationals deputy leader Nigel Scullion as leader of the Nationals in the Senate, and stated that his party in the upper house would no longer necessarily vote with their Liberal counterparts in the upper house, which opened up another possible avenue for the Rudd Labor Government to get legislation through.[41][42] Joyce was elected leader in a party-room ballot on 11 February 2016, following the retirement of former leader and Deputy Prime Minister Warren Truss.[43][44][45][46] Joyce was one of five politicians disqualified from parliament in October 2017 for holding dual citizenship, along with former deputy leader, Fiona Nash.

Liberal/National merger

Merger plans came to a head in May 2008, when the Queensland state Liberal Party gave an announcement not to wait for a federal blueprint but instead to merge immediately. The new party, the Liberal National Party, was founded in July 2008.

Historical electoral results

| Election | Leader | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | Position | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1919* | none | 176,884 | 9.3 | 11 / 75 |

Crossbench | ||

| 1922 | Earle Page | 197,513 | 12.5 | 14 / 75 |

Coalition | ||

| 1925 | Earle Page | 313,363 | 10.7 | 13 / 75 |

Coalition | ||

| 1928 | Earle Page | 271,686 | 10.4 | 13 / 75 |

Coalition | ||

| 1929 | Earle Page | 295,640 | 10.2 | 10 / 75 |

Opposition | ||

| 1931 | Earle Page | 388,544 | 12.2 | 16 / 75 |

Crossbench | ||

| 1934 | Earle Page | 447,968 | 12.6 | 14 / 74 |

Coalition | ||

| 1937 | Earle Page | 560,279 | 15.5 | 16 / 74 |

Coalition | ||

| 1940 | Archie Cameron | 531,397 | 13.7 | 13 / 74 |

Coalition | ||

| 1943 | Arthur Fadden | 287,000 | 6.9 | 7 / 74 |

Opposition | ||

| 1946 | Arthur Fadden | 464,737 | 10.7 | 11 / 76 |

Opposition | ||

| 1949 | Arthur Fadden | 500,349 | 10.8 | 19 / 121 |

Coalition | ||

| 1951 | Arthur Fadden | 443,713 | 9.7 | 17 / 121 |

Coalition | ||

| 1954 | Arthur Fadden | 388,171 | 8.5 | 17 / 121 |

Coalition | ||

| 1955 | Arthur Fadden | 347,445 | 7.9 | 18 / 122 |

Coalition | ||

| 1958 | John McEwen | 465,320 | 9.3 | 19 / 122 |

Coalition | ||

| 1961 | John McEwen | 446,475 | 8.5 | 17 / 122 |

Coalition | ||

| 1963 | John McEwen | 489,498 | 8.9 | 20 / 122 |

Coalition | ||

| 1966 | John McEwen | 561,926 | 9.8 | 21 / 124 |

Coalition | ||

| 1969 | John McEwen | 523,232 | 8.5 | 20 / 125 |

Coalition | ||

| 1972 | Doug Anthony | 622,826 | 9.4 | 20 / 125 |

Opposition | ||

| 1974 | Doug Anthony | 736,252 | 9.9 | 21 / 127 |

Opposition | ||

| 1975 | Doug Anthony | 869,919 | 11.2 | 23 / 127 |

Coalition | ||

| 1977 | Doug Anthony | 793,444 | 10.0 | 19 / 124 |

Coalition | ||

| 1980 | Doug Anthony | 745,037 | 8.9 | 20 / 125 |

Coalition | ||

| 1983 | Doug Anthony | 799,609 | 9.2 | 17 / 125 |

Opposition | ||

| 1984 | Ian Sinclair | 921,151 | 10.6 | 21 / 148 |

Opposition | ||

| 1987 | Ian Sinclair | 1,060,976 | 11.5 | 19 / 148 |

Opposition | ||

| 1990 | Charles Blunt | 833,557 | 8.4 | 14 / 148 |

Opposition | ||

| 1993 | Tim Fischer | 758,036 | 7.1 | 16 / 147 |

Opposition | ||

| 1996 | Tim Fischer | 893,170 | 7.1 | 18 / 148 |

Coalition | ||

| 1998 | Tim Fischer | 588,088 | 5.2 | 16 / 148 |

Coalition | ||

| 2001 | John Anderson | 643,926 | 5.6 | 13 / 150 |

Coalition | ||

| 2004 | John Anderson | 690,275 | 5.8 | 12 / 150 |

Coalition | ||

| 2007 | Mark Vaile | 682,424 | 5.4 | 10 / 150 |

Opposition | ||

| 2010 | Warren Truss | 419,286 | 3.4 | 12 / 150 [Note 3] |

Opposition | ||

| 2013 | Warren Truss | 554,268 | 4.2 | 15 / 150 [Note 1] |

Coalition | ||

| 2016 | Barnaby Joyce | 624,555 | 4.6 | 16 / 150 [Note 1] |

Coalition | ||

| 2019 | Michael McCormack | 642,233 | 4.5 | 16 / 150 [Note 1] |

Coalition |

- Including the 5 LNP MPs who sit in the National party room.

- Including the 2 LNP Senators and 1 CLP Senator who sit in the National party room

- Including the 5 LNP MPs who sit in the National party room

Leadership

List of leaders

| # | Leader | Term start | Term end | Time in office | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | William McWilliams | 24 February 1920 | 5 April 1921 | 1 year, 40 days | ||

| 2 |  |

Earle Page | 5 April 1921 | 13 September 1939 | 18 years, 161 days | Prime Minister: 1939 Deputy PM: 1923–29, 1934–39 |

| 3 |  |

Archie Cameron | 13 September 1939 | 16 October 1940 | 1 year, 33 days | Deputy PM: 1940 |

| 4 |  |

Arthur Fadden | 16 October 1940 acting until 12 March 1941 | 12 March 1958 | 17 years, 147 days | Prime Minister: 1941 Deputy PM: 1940–41, 1949–58 |

| 5 |  |

John McEwen | 26 March 1958 | 1 February 1971 | 12 years, 312 days | Prime Minister: 1967–68 Deputy PM: 1958–67, 1968–71 |

| 6 |  |

Doug Anthony | 2 February 1971 | 17 January 1984 | 12 years, 349 days | Deputy PM: 1971–72, 1975–83 |

| 7 |  |

Ian Sinclair | 17 January 1984 | 9 May 1989 | 4 years, 113 days | |

| 8 | Charles Blunt | 9 May 1989 | 6 April 1990 | 332 days | ||

| 9 |  |

Tim Fischer | 19 April 1990 | 1 July 1999 | 9 years, 73 days | Deputy PM: 1996–99 |

| 10 | .jpg) |

John Anderson | 1 July 1999 | 23 June 2005 | 5 years, 357 days | Deputy PM: 1999–2005 |

| 11 | .jpg) |

Mark Vaile | 23 June 2005 | 3 December 2007 | 2 years, 163 days | Deputy PM: 2005–07 |

| 12 |  |

Warren Truss | 7 December 2007 | 11 February 2016 | 8 years, 66 days | Deputy PM: 2013–16 |

| 13 |  |

Barnaby Joyce | 11 February 2016 | 26 February 2018 | 2 years, 14 days | Deputy PM: 2016–2018 |

| 14 |  |

Michael McCormack | 26 February 2018 | 2 years, 123 days | Deputy PM: 2018– | |

List of deputy leaders

| Order | Name | Term start | Term end | Time in office | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Edmund Jowett | 24 February 1920 | 5 April 1921 | 1 year, 40 days | McWilliams |

| 2 | Henry Gregory | 5 April 1921 | 2 December 1921 | 241 days | Page |

| vacant | 23 February 1922 | 27 June 1922 | |||

| 3 | William Fleming | 27 June 1922 | 16 January 1923 | 203 days | |

| 4 | William Gibson | 16 January 1923 | 19 November 1929 | 6 years, 307 days | |

| 5 | Thomas Paterson | 19 November 1929 | 27 November 1937 | 8 years, 8 days | |

| 6 | Harold Thorby | 2 years, 262 days | |||

| 27 November 1937 | 15 October 1940 | Cameron | |||

| 7 | Arthur Fadden | 15 October 1940 | 12 March 1941 | 148 days | vacant |

| vacant | 12 March 1941 | 22 September 1943 | Fadden | ||

| 8 | John McEwen | 22 September 1943 | 26 March 1958 | 14 years, 185 days | |

| 9 | Charles Davidson | 26 March 1958 | 11 December 1963 | 5 years, 260 days | McEwen |

| 10 | Charles Adermann | 11 December 1963 | 8 December 1966 | 2 years, 362 days | |

| 11 | Doug Anthony | 8 December 1966 | 2 February 1971 | 4 years, 56 days | |

| 12 | Ian Sinclair | 2 February 1971 | 17 January 1984 | 12 years, 349 days | Anthony |

| 13 | Ralph Hunt | 17 January 1984 | 24 July 1987 | 3 years, 188 days | Sinclair |

| 14 | Bruce Lloyd | 5 years, 242 days | |||

| 24 July 1987 | 23 March 1993 | Blunt | |||

| Fischer | |||||

| 15 | John Anderson | 23 March 1993 | 1 July 1999 | 6 years, 100 days | |

| 16 | Mark Vaile | 1 July 1999 | 23 June 2005 | 5 years, 357 days | Anderson |

| 17 | Warren Truss | 23 June 2005 | 3 December 2007 | 2 years, 163 days | Vaile |

| 18 | Nigel Scullion | 3 December 2007 | 13 September 2013 | 5 years, 284 days | Truss |

| 19 | Barnaby Joyce | 13 September 2013 | 11 February 2016 | 2 years, 151 days | |

| 20 | Fiona Nash | 11 February 2016 | 7 December 2017 | 1 year, 299 days | Joyce |

| 21 | Bridget McKenzie | 7 December 2017 | 2 February 2020 | ||

| 2 years, 57 days | McCormack | ||||

| 22 | David Littleproud | 4 February 2020 | Incumbent | 144 days | |

List of Senate leaders

The Country Party's first senators began their terms in 1926, but the party had no official leader in the upper chamber until 1935. Instead, the party nominated a "representative" or "liaison officer" where necessary – usually William Carroll. This was so that its members "were first and foremost representatives of their states, able to enjoy complete freedom of action and speech in the Senate and not beholden to the dictates of [...] a party Senate leader". On 3 October 1935, Charles Hardy was elected as Carroll's replacement and began using the title "Leader of the Country Party in the Senate". This usage was disputed by Carroll and Bertie Johnston, but a subsequent party meeting on 10 October confirmed Hardy's position.[47] However, after Hardy's term ended in 1938 (due to his defeat at the 1937 election), the party did not elect another Senate leader until 1949 – apparently due to its small number of senators.[48]

| # | Name | Term start | Term end | Time in office | Deputy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Charles Hardy | 10 October 1935 | 30 June 1938 | 2 years, 263 days | |

| vacant | 30 June 1938 | 1949 | |||

| 2 | Walter Cooper | 1949 | 1960 | ||

| 3 | Harrie Wade | 1961 | 1964 | ||

| 4 | Colin McKellar | 1964 | 1969 | ||

| 5 | Tom Drake-Brockman | 1969 | 1975 | ||

| 6 | James Webster | 1976 | 1980 | ||

| 7 | Douglas Scott | February 1980 | 30 June 1985 | ||

| 8 | Stan Collard | 1 July 1985 | 5 June 1987 | 1 year, 339 days | |

| 9 | John Stone | 21 August 1987 | 1 March 1990 | 2 years, 192 days | |

| 10 | Ron Boswell | 10 April 1990 | 3 December 2007 | 17 years, 237 days | Sandy Macdonald |

| 11 | Nigel Scullion | 3 December 2007 | 17 September 2008 | 289 days | Ron Boswell |

| 12 | Barnaby Joyce | 17 September 2008 | 8 August 2013 | 4 years, 325 days | Fiona Nash |

| (11) | Nigel Scullion | 8 August 2013 | 28 May 2019 | 5 years, 293 days | |

| 13 | Bridget McKenzie | 28 May 2019 | incumbent | 1 year, 30 days | Matt Canavan |

Current state and territory leaders

| State/Territory | Branch | Leader | Term began | Time in office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSW | NSW Nationals | John Barilaro | November 2016 | 3 years, 225 days | Also Deputy Premier of New South Wales |

| VIC | The Nationals Victoria | Peter Walsh | December 2014 | 5 years, 209 days | Leader |

| QLD | Liberal National Party of Queensland [n 1] | Deb Frecklington | December 2017 | 2 years, 198 days | Leader |

| WA | The Nationals WA | Mia Davies | March 2017 | 3 years, 98 days | Leader |

| NT | Country Liberal Party [n 2] | Gary Higgins | September 2016 | 3 years, 299 days | Leader |

- The Liberal National Party of Queensland (LNP) is the result of merger of the Queensland Division of the Liberal Party and the Queensland branch of the National Party to contest elections as a single party

- In the Northern Territory, the Country Liberal Party endorses National candidates for the Senate and Liberal candidates for the House of Representatives.

As of November 2019, the party does not have federal or state representation in Tasmania or South Australia, though the Tasmanian and South Australian branches last contested in the 2019 Australian federal election. The National Party does not have a branch in the Australian Capital Territory.

Past Premiers

Queensland

|

Victoria

|

Donors

For the 2015-2016 financial year, the top ten disclosed donors to the National Party were: Manildra Group ($182,000), Ognis Pty Ltd ($100,000), Trepang Services ($70,000), Northwake Pty Ltd ($65,000), Hancock Prospecting ($58,000), Bindaree Beef ($50,000), Mowburn Nominees ($50,000), Retail Guild of Australia ($48,000), CropLife International ($43,000) and Macquarie Group ($38,000).[49][50]

The National Party also receives undisclosed funding through several methods, such as "associated entities". John McEwen House, Pilliwinks and Doogary are entities which have been used to funnel donations to the National Party without disclosing the source.[51][52][53][54]

See also

- Young Nationals (Australia)

- Leader of the New South Wales National Party

- Katter's Australian Party

- National Party of Australia leadership spill, 2007

Further reading

- Aitkin, Don. The country party in New South Wales (1972)

- Aitkin, Don. "'Countrymindedness': The Spread of an Idea", ACH: The Journal of the History of Culture in Australia, April 1985, Vol. 4, pp 34–41

- Davey, Paul. The Nationals: the Progressive, Country, and National Party in New South Wales 1919–2006 (2006)

- Davey, Paul. "Politics in the Blood – The Anthonys of Richmond" (2008)

- Davey, Paul. "Ninety Not Out – The Nationals 1920-2010" (2010)

- Davey, Paul. "The Country Party Prime Ministers – Their Trials and Tribulations" (2011)

- Duncan, C.J. "The demise of 'countrymindedness': New players or changing values in Australian rural politics?" Political Geography, Sep 1992, Vol. 11 Issue 5, pp 430–448

- Graham, B. D. "Graziers in Politics, 1917 To 1929", Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand, 1959, Vol. 8 Issue 32, pp 383–391

- Leithner, Christian. "Rational Behaviour, Economic Conditions and the Australian Country Party, 1922–1937", Australian Journal of Political Science, July 1991, Vol. 26 Issue 2, pp 240–259

- Williams, John R. "The Organization of the Australian National Party", Australian Quarterly, 1969, Vol. 41 Issue 2, pp 41–51,

Notes

References

- Kenny, Mark (26 February 2018). "Michael McCormack new Deputy Prime Minister, Nationals leader". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 26 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- Aitkin, (1972); Graham, (1959)

- "That Alleged Country Party". The Richmond River Herald and Northern Districts Advertiser. NSW: National Library of Australia. 4 July 1913. p. 2. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- "CORANGAMITE". The North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times. Tas.: National Library of Australia. 21 December 1918. p. 5. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- Neilson, W. (1986) 'McWilliams, William James (1856–1929)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 10, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne.

- B.D. Graham, "Graziers in Politics, 1917 To 1929", Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand, 1959, Vol. 8 Issue 32, pp 383–391

- Davey (2006)

- Davey (2005)

- J. M. Barbalet, "Tri-Partism in Australia: The Role of the Australian Country Party", Politics (00323268), 1975, Vol. 10 Issue 1, pp. 1–11

- Joseph Bindloss, Queensland (2002) p. 24

- Jeremy Moon and Campbell Sharman, Australian politics and government (2003) p. 228

- Green, Antony. "Where to now for the Nationals?". ABC News Online. ABC. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- Davey, Paul (2008). Politics in the Blood: The Anthonys of Richmond. Sydney: UNSW Press. pp. 169–170. ISBN 9781921410239.

- Davey, Paul (2006). The Nationals: The Progressive, Country, and National Party in New South Wales 1919–2006. Sydney: Federation Press. p. 244. ISBN 9781862875265.

- "The National Party's Recent Decline". ABC News Online. ABC. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- "Barnaby Joyce: a rebel without a pause button". Sydney Morning Herald. 17 February 2018. Archived from the original on 7 August 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- "Australian legislative election of 24 March 1990". Psephos. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- "Australian legislative election of 2 March 1996". Psephos. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- Stephen, Barber. "Federal election results 1901–2016". Parliament of Australia. Australian Government'. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

-

- "Joyce confirms marriage split". NewsComAu.

- "Bundle of Joyce: Birth of a National". Daily Telegraph. 6 February 2018.

- "Barnaby Joyce: a rebel without a pause button". Sydney Morning Herald. 17 February 2018. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- "Sex ban for ministers and staff following Joyce's 'shocking error of judgment': Turnbull". SBS. 16 February 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- "Barnaby to face leadership challenge". NewsComAu.

- "Barnaby Joyce resigns as Nationals leader, Deputy PM". ABC News (Australia). 23 February 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- Nationals members foot the bill for Barnaby Joyce's 'exceptional' byelection salary

- Barnaby Joyce resigns as Nationals leader, deputy prime minister

- Karp, Paul; Hutchens, Gareth (23 February 2018). "Barnaby Joyce quits as Australia's deputy prime minister and Nationals leader". the Guardian.

- Yaxley, Louise. "Nationals unable to make a finding in Barnaby Joyce sexual harassment case launched by Catherine Marriott." "ABC News, 7 September 2018

- An abridged list of articles discussing neo-Nazi infiltration:

- "'These guys are crazy': Barnaby Joyce backs 'Nazi' expulsions after backtrack". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- "Nationals clear man accused of leading alleged neo-Nazi branch stacking". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- Hutchins, Gareth. "Far right extremists 'not welcome' in Nationals, leader says amid investigation". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- Michael, McGowen. "NSW Young Nationals expel and suspend members over far-right links". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- "First preferences by party". Tally Room. Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "The Nationals Parliamentary Party". The Nationals. Archived from the original on 18 November 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Wanna, John; Arklay, Tracey. The Ayes Have It: The History of the Queensland Parliament, 1957–1989.

- Matt Smith (30 January 2014). "Federal National Party director expresses concern over non-aligned party running in Tasmanian poll". Mercury. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- "Moves underway to set up a Tasmania Party to contest future elections". ABC News. 26 November 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- "Party Register". Tasmanian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- Sue Bailey (29 May 2018). "Senator Steve Martin will struggle to get elected at the next poll says a Tasmanian academic". Examiner. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- Libs 'involved' in McGauran defection, The Age, 30 January 2006

- "Victoria election 2014: National Party to 'review' coalition with Liberals in Victoria". ABC News. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Peter Ryan stands down as leader of Victorian National Party". ABC News. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Matthew Guy elected as new Liberal Party leader in Victoria". ABC News. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Labor's clean sweep broken". News.com.au. Sydney. 14 September 2008. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- Carr, Adam. "1974 House of Representatives: National and state summaries". Psephos Election Archive. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- "List of elected candidates - 1989 Election". Elections ACT. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- "First Preference Results - 1989 Election". Elections ACT. 6 January 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- Rae Wear, "Countrymindedness Revisited", (Australian Political Science Association, 1990) online edition Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Don Aitkin, "'Countrymindedness': The Spread of an Idea", ACH: The Journal of the History of Culture in Australia, April 1985, Vol. 4, pp. 34–41

- C.J. Duncan, "The demise of 'countrymindedness': New players or changing values in Australian rural politics?" Political Geography, Sep 1992, Vol. 11 Issue 5, pp. 430–448

- "Senator McGauran quits Nationals – National". theage.com.au. Melbourne. 23 January 2006. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- "Nationals won't toe Libs' line: Joyce". The Sydney Morning Herald. 18 September 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- Berkovic, Nicola (18 September 2008). "Leader Barnaby Joyce still a maverick". The Australian. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- Murphy, Katharine (11 February 2016). "Barnaby Joyce wins Nationals leadership, Fiona Nash named deputy". The Guardian. Australia. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- Gartrell, Adam (11 February 2016). "Parliament pays tribute to retiring deputy PM Warren Truss ahead of Barnaby Joyce elevation". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- Keany, Francis (11 February 2016). "Barnaby Joyce elected unopposed as new Nationals leader". ABC News. Australia. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- "Truss wins Nationals leadership". ABC News. Australia. 3 December 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- Paul Davey (2010). Ninety Not Out: The Nationals 1920–2010. UNSW Press. p. 57. ISBN 9781742231662.

- Davey (2010), p. 58.

- "Donor Summary by Party Group". www.periodicdisclosures.aec.gov.au. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Donor Summary by Party". www.periodicdisclosures.aec.gov.au. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Australian political donations: Who gave how much?". Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- "John McEwen House Pty Ltd". Archived from the original on 7 September 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- "Pilliwinks Pty Ltd as Trustee National Party Foundation". Archived from the original on 7 September 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- "Disclosure rules far from revealing". Retrieved 7 September 2017.