Moshe Ha-Elion

Moshe Ha-Elion (also written Moshe Haelion, Moshe 'Ha-Elion, Moshé Ha-Elion, Moshé 'Ha-Elion, Moshé Haelyon) is a Holocaust survivor and writer. He was born in Thessaloniki, Greece, on February 26, 1925. He survived Auschwitz, the death march, Mauthausen, Melk, and Ebensee. He is the author of a memoir, מיצרי שאול (Meizarey Sheol), originally written in Hebrew and translated into English as The Straits of Hell: The chronicle of a Salonikan Jew in the Nazi extermination camps Auschwitz, Mauthausen, Melk, Ebensee. He wrote three poems in Ladino based on his experience in the concentration camps and the death march: "La djovenika al lager", "Komo komian el pan", and "En marcha de la muerte", published in Ladino and Hebrew under the title En los Kampos de la Muerte. Moshe Ha-Elion has translated Homer's Odyssey into Ladino.[1] He lives in Israel. He has two children, six grandchildren, and five great-grandchildren.

Biography: before deportation

Moshe Ha-Elion was born in Thessaloniki, Greece, on February 26, 1925. He came from a middle-class Sephardic Jewish family. Moshe's grandfather was a rabbi. Moshe's father, Eliau, worked as a bookkeeper in a shop. His mother, Rachel, was a housewife.[2] His sister (a year and a half younger than him) was Ester (Nina). The family spoke Ladino at home. Outside the house, they spoke Greek. Moshe also learned Hebrew.[2] Moshe studied at the Primary School "Talmud Torá" of the Jewish Community of Thessaloniki. The principal of the school was Moshe's uncle (Moshe's father's brother).[3] Afterwards, he continued his studies at a public Greek gymnasium in Thessaloniki.[4]

In 1936 there were some anti-Semitic attacks in Thessaloniki. Moshe was then 11 years old. Although his family was Zionist, they never thought of leaving Thessaloniki. When the Germans invaded Thessaloniki (April 9, 1941), everything changed: "When the Germans entered, we [felt] a big fear ... because we knew from the newspapers what happened in Germany: the Kristallnacht, the persecutions."[2] Moshe's father died on April 15, 1941, six days after the Germans invaded Thessaloniki.

In the summer of 1942, the persecution of the Jews of Thessaloniki started.[5] On July 11, 1942, all Jewish men between the ages of 18 and 45 were ordered to concentrate in the Independence Square of Thessaloniki for "registration". In the square, the Jews suffered their first humiliations: the Germans forced them to do gymnastics in the hot weather and didn't allow them to drink water.[2][5] Moshe and the rest of the Jewish community of Thessaloniki were informed by German Nazi officials that they would all be relocated to Poland.[6] Then, Jews were ordered to wear the Yellow Star of David and forced into two ghettos, one in the east of Thessaloniki and one in the western, called Baron Hirsch, adjacent to the rail lines.[5][7]

On March 15, 1943, the Germans began deporting Jews from Thessaloniki. Every three days, freight cars crammed with an average of 2,000 Thessaloniki Jews headed toward Auschwitz-Birkenau. By the summer of 1943, the Germans had deported 46,091 Jews.[5] Most of the deportees were gassed on arrival in Auschwitz-Birkenau.[7]

Auschwitz

The first transport of Jews from Thessaloniki to Poland left on March 15, 1943. All transports left from the Baron Hirsch ghetto.[6]

On April 4, 1943 Moshe and his family (his mother and sister, both of Moshe's maternal grandparents, his uncle with his wife and their one year old child) were ordered to the Baron Hirsch ghetto believing that from there they will be transported and resettled in Poland.[6] They packed their bags which included warm clothing they bought especially for settling in Poland, left their keys with their non-Jewish neighbors and moved to the Baron Hirsch ghetto.[6]

In the morning of April 7, 1943 Moshe and his family were transported in freight wagons packed with people. They travelled for six days and nights. He describes the deportation in his poem "La djovenika al lager".[8] On the night of April 13 they arrived to Auschwitz.

Moshe's mother and sister were gassed upon arrival. Moshe's maternal grandparents, his uncle's wife and his one-year-old son were also gassed upon arrival.[4] Moshe's uncle was murdered in Auschwitz some months later.

By August 1943, 46,091 Greek Jews were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Of those, 1,950 survived. Fewer than 5,000 of the 80,000 Jews living in Greece survived. The majority, after being rescued from the camps, emigrated to Israel.[9]

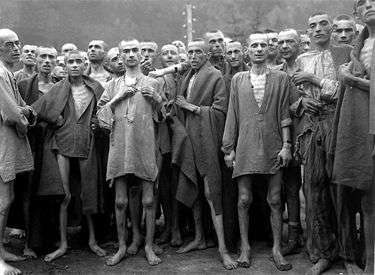

Moshe Ha-Elion was tattooed in Auschwitz with the number 114923 on his left arm.[6] He worked in forced labour in Auschwitz I for 21 months, until 1945.[6] "Auschwitz was hell (...) It was a place where you never knew if you were going to be alive the next minute. A place where children could not live... they were condemned to die, as well as their mothers. Only the ones that could work could live for some time. The rest, to death".[10]

Death march

On January 21, 1945, Moshe was forced, together with thousands of prisoners, to march. He describes the death march in his poem "En marcha de la muerte".[11] Every now and then, Moshe could hear the guns killing the victims who could no longer walk.[12] On the second day they arrived at a train station. The prisoners were put inside freight wagons without water or food.[12][3] After three days, they arrived at Mauthausen.

Mauthausen, Melk and Ebensee

Moshe was forced to work at Mauthausen concentration camp and then he was transferred to Melk, where he worked as a forced labourer in a munitions factory, inside the mountains, in tunnels.[3] When the Allies were approaching the camps, the Germans took the prisoners through the Danube in small boats to the city of Linz and then, after four days by foot, to Ebensee.[3]

Mauthausen, Melk and Ebensee were located in Austria which was a part of Nazi Germany. The hunger was atrocious. Moshe had to eat carbon to survive.[12] In his poem "Komo komian el pan",[13] Moshe writes that during his years as a prisoner in the Nazi concentration camps his stomach was always crying.

Liberation

On May 6, 1945, one week after Hitler's death, the American army liberated all the sub-camps of Mauthausen, including Ebensee, where Moshe Ha-Elion was a prisoner. Three American tanks entered Ebensee. Some prisoners were touching them to be sure that they were real.[12] Some inmates were crying, some were shouting.[12] Moshe Ha-Elion recalls that the Polish inmates were singing the Polish hymn, the Greek inmates were singing the Greek hymn[12] and the French inmates were singing La Marseillaise.[3] After, the Jewish inmates were singing Ha Tikvah.[3]

After the war

After the liberation, Moshe Ha-Elion decided not to come back to Thessaloniki, and illegally emigrated to Palestine on board the Wedgewood boat in June 1946, after being in the south of Italy for one year. The boat was taken by the English army. Moshe was imprisoned for one month in a British camp in Atlit (located in British Mandatory Palestine).

Work, studies and Remembering the Shoah Organizations after the war

Moshe Ha-Elion fought in the Israeli Independence War. In 1950 he became an officer in the artillery division of the IDF. In 1970 he retired from his military career as a lieutenant colonel and finally in 1976, while serving in the reserved forces, he was named colonel. Moshe worked in the Israeli Ministry of Defense and was first an assistant and then head of an operational unit. He then worked for the administration until he retired.

Moshe got his Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) and master's degree (M.A.) in Humanitas from the University of Tel-Aviv.

Moshe Ha-Elion was the president of the "Asosiasión de los Reskapados de los Kampos de Eksterminasión, Orijinarios de Grecha en Israel" (Association of the Holocaust Survivors from Greece in Israel) from 2001 until 2015. Before that, and for 25 years, he was a member of the Association and vice president. After 2015 he received the title of Honorary President of the Association.

Moshe Ha-Elion has been a member of the board of Yad Vashem for more than 10 years.[14] He has also been a member of the board of the Lión Recanati CASA and Honorary President of the "Chentro de Erensia de las komunidades de Saloniki i de Grecha" (Center of Heritage of the Saloniki and Greece Communities).

Coming back to Auschwitz

Moshe Ha-Elion returned to Auschwitz several times in order to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust. In March 1987 he visited the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum together with his daughter, a group of other survivors and a radio crew of the Israeli radio station "Galei Zahal".[6]

Moshe says that he has been in Auschwitz 15 times, but, he remarks ironically, the first one was against his will.[12]

The message of Moshe Ha-Elion is: "The world must not forget (...) The Jewish people we are always going to remember, but the whole world has to know what happened".[10]

In 2015, Moshe said: "Two years ago I was in Auschwitz, with my daughter and my granddaughter, and my granddaughter was pregnant. We were there, four generations, at the place where they tried to kill me. That's my victory".[10]

Personal life

Moshe's father died on April 15, 1941, just a few days after the Nazis invaded Thessaloniki (April 9, 1941). Moshe's mother and sister were gassed in Auschwitz upon arrival (April 13, 1943). On February 2, 1947, Moshe married Haná Waldman in Palestine, whom he had met in Italy. They had a daughter called Rahel and a son called Elí. Today Moshe has six grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. His wife Haná Waldman passed away on September 1, 2010.

Works and Compositions

In 1992 Moshe Ha-Elion published an autobiography called מיצרי שאול (Meizarey Sheol) written in Hebrew and translated into English in 2005 with the title The Straits of Hell. The chronicle of a Salonikan Jew in the Nazi extermination camps Auschwitz, Mauthausen, Melk, Ebensee.

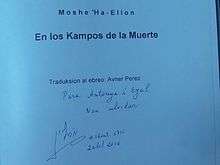

In 2000 Moshe Ha-Elion published En los Kampos de la Muerte, a poetic and autobiographical text written in Ladino and formed of three very large poems: "La djovenika al lager" (dedicated to his sister); "Komo komian el pan"; and "En marcha de la muerte" (poem that describes his death march).

Moshe Ha-Elion also composed music for the first poem of En los Kampos de la Muerte: "La djovenika al lager".[15]

En los Kampos de la Muerte has been adapted to a theater-music-poetic show by baroque ensemble Rubato Appassionato and actor Gary Shochat.[16]

Bibliography & Editions

- מיצרי שאול. Written & published in Hebrew. Magav Mada Vetechnologia Ltd. Tel-Aviv, 1992.

- En los Kampos de la Muerte. Originally written in Ladino. Hebrew translation by Avner Perez. Bilingual edition in Ladino & Hebrew. Published by Instituto Maale Adumim, Maale Adumim, Israel, 2000.

- The Straits of Hell. The chronicle of a Salonikan Jew in the Nazi extermination camps Auschwitz, Mauthausen, Melk, Ebensee. (English translation of מיצרי שאול). Mannheim: Bibliopolis and Cincinnati: BCAP, 2005. Steven B. Bowman, editor.

- Las Angustias del Enferno: Las pasadias de un Djidio de Saloniki en los kampos de eksterminasion almanes Auschwitz, Mauthausen, Melk i Ebensee (Ladino translation of מיצרי שאול). Language: Ladino. Published by Sentro Moshe David Gaon de Kultura Djudeo-Espanyola / Universidad Ben-Gurion del Negev, 2007

- The Straits of Hell: The Chronicle of a Salonikan Jew in the Nazi Extermination Camps Auschwitz, Mauthausen, Melk, Ebensee (Peleus). (English translation of מיצרי שאול). Published by Otto Harrassowitz, 2009. ISBN 9783447059763

- Shay Le-Navon - La Odisea Trezladada en Ladino i Ebreo del Grego Antiguo: Prezentada kon Estima i Afeksion a Yitshak Navon, Sinken Prezidente de Israel i Prezidente de la Autoridad Nasionala del Ladino al Kumplir Noventa Anios [TWO VOLUME SET]. Homer / Ha-Elion, Moshe; Perez, Avner [Trans.] Published by Yeriot, 2011 & 2014

References

- Nir Hasson (9 March 2012). "Haaretz". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- Oral history interview with Moshe Haelion. USHMM. http://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn532733

- Shalom - Moshe Haelion: http://www.rtve.es/alacarta/videos/shalom/shalom-moshe-haelion/3594098/ (May 1, 2016)

- Yad Vashem: http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/about/events/pope/francis/meeting.asp

- USHMM. Thessaloniki: https://www.ushmm.org/information/exhibitions/online-features/special-focus/holocaust-in-greece/thessaloniki

- Moshe Ha Elion. מיצרי שאול. Magav Mada Vetechnologia Ltd. Tel-Aviv, 1992.

- USHMM. Salonika: https://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005422

- "La djovenika al lager". En los Kampos de la Muerte, p. 15. Maale Adumim, Israel, 2000.

- Costas Kantouris: Jews in Greece mark WWII Nazi deportation. March 17, 2013: https://www.yahoo.com/news/jews-greece-mark-wwii-nazi-deportation-223745848.html?ref=gs

- Moshe Haelion, sobreviviente de Auschwitz. Grabado en la memoria: http://www.montevideo.com.uy/auc.aspx?260574 (January 28, 2015)

- "En marcha de la muerte". En los Kampos de la Muerte, pp. 42-87. Maale Adumim, Israel, 2000.

- Moshé Haelion, el verbo del horror nazi llamado Auschwitz: http://www.elmundo.es/la-aventura-de-la-historia/2016/01/27/56a7b0ea46163f06028b45e4.html (El Mundo, January 27, 2016)

- "Komo komian el pan". En los Kampos de la Muerte, p. 39. Maale Adumim, Israel, 2000.

- Yad Vashem Magazine. Volume 80. June 2016: http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/pressroom/magazine/pdf/yv_magazine80.pdf

- "La djovenika al lager". En los Kampos de la Muerte, p. 20. Maale Adumim, Israel, 2000.

- Rubato Appassionato. En los Kampos de la Muerte. Poems by Moshe 'Ha-Elion: http://www.rubatoappassionato.com/en-los-kampos-de-la-muerte.html

External links

- Moshe Ha-Elion talks about the deportation of the Jews of Thessaloniki to the extermination Nazi camps. In Ladino. Yad Vashem.

- Moshe Ha-Elion talks about the transfer and arrival to Auschwitz. In Ladino. Yad Vashem.

- Moshe Ha-Elion talks about the arrival at Auschwitz and the selection. In Hebrew.

- Testimony of Holocaust survivor Moshe Ha-Elion. In Hebrew.

- Moshe Ha-Elion. Historia de un superviviente. In Ladino.

- Moshe Ha-Elion. Testimony. In Ladino. Shalom / RTVE

- Moshe Ha-Elion. Sopravvissuto alla Shoah. In Italian.

- Moshe Ha-Elion. La testimonianza di uno dei sopravvissuti alla Shoah. Papa Francesco in Terra Santa. In Italian & English

- Oral history interview with Moshe Haelion. In English. USHMM.

- "La djovenika al lager". Jewish Community Choir of Thessaloniki. Kostis Papazoglou, conductor. Music & poem by Moshe Ha Elion. Recited in Ladino by Moshe Ha Elion.

- En los Kampos de la Muerte. A show created by Rubato Appassionato and Gary Shochat based on the work by Moshe 'Ha-Elion.

- Yad Vashem. The World Holocaust Remembrance Center.

- The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. USHMM.