Moses Jacob Ezekiel

Moses Jacob Ezekiel, also known as Moses "Ritter von" Ezekiel (October 28, 1844 – March 27, 1917), was a Sephardic Jewish-American sculptor who lived and worked in Rome for the majority of his career. Ezekiel was "the first American-born Jewish artist to receive international acclaim."[1]

Moses Jacob Ezekiel | |

|---|---|

Moses Jacob Ezekiel in 1914 | |

| Born | October 28, 1844 Richmond, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | March 27, 1917 (aged 72) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Virginia Military Institute |

| Known for | Sculpture |

Among his numerous honors and prizes was the title of Cavaliere given by the Italian government. At the age of 29, Ezekiel was the first foreigner to win the Michel-Beer Prix de Rome.

He had been a cadet at the Virginia Military Institute and served on the Confederate side in the American Civil War, including at the Battle of New Market. He is the only well-known sculptor to have seen action in the Civil War.[2]

After the war, he completed his degree at VMI, and a few years later went to Berlin, where he studied at the Prussian Academy of Art. He moved to Rome, where he lived and worked most of his life, selling his works internationally, including as commissions in the United States. He has been described as a "Confederate expatriate".[2]

Ezekiel was a "proud Southerner",[3] and the Confederate battle flag hung in his Rome studio for 40 years.[2] He was a postwar friend of Robert E. Lee, who recommended he become "an artist".[2][3][4]:124 Some of the most celebrated statues by Ezekiel were of heroes of the Confederacy. The most famous of his monuments is the Confederate Memorial in Arlington National Cemetery, which he thought of as the "crowning achievement of his career."[5] However, despite entering at least four contests to make a public sculpture of Robert E. Lee — "the one work I would love to do above anything else in the world"[4]:171 — it did not come to fruition.[2]

Childhood

Ezekiel was born in Richmond, Virginia, the son of Jacob Ezekiel (1812–1899), who was Ashkenazic; his mother, Catherine de Castro Ezekiel, was Sephardic.[6][7] His grandparents had emigrated from Holland (a Sephardic center) in the early 1800s, settling first in Philadelphia and later in Richmond.[8]:3 His father was a cotton merchant[7] and bookbinder, "a good writer and a well-read man, who possessed the complete works of Maimonides";[4]:76 while in the book-binding business in Baltimore (1833–34), he founded the Hebrew Benevolent Society of Baltimore.[9] Jacob moved to Richmond in 1834, entering the dry-goods business with first one, then another brother-in-law.[10]:16 n. 10 He was Secretary of the synagogue Kahal Kadosh Beth Shalome "and spokesman of the Jews of Richmond",[10]:16 n. 10 and later, in Cincinnati, was Secretary of the Board of Hebrew Union College. He was a charter member of B'nai B'rith.[11]

Moses had three brothers and eight sisters;[12] another source says he had 4 brothers and 9 sisters;[8]:3 at least one was stillborn.[4]:88 He was the 7th child;[8]:3 another source says he was 5th of 14.[9][10]:14 Although he was not observant as an adult, he was brought up as an observant Jew by his grandparents, where his parents sent him because of financial problems.[3][8]:3 ("My father was so very good-hearted that he ruined himself by signing bonds for some of his relatives who afterwards failed in business. That reduced my parents to absolute poverty for a long time."[4]:88) They owned a dry-goods store that sold suits and women's dresses for slaves about to be sold; they also owned a few slaves.[2][5] He "was sent to a 'pay' school", that of "old Mr. Burton Davis".[4]:91 He also attended dancing school.[4]:85, 101

Alice Johnson

Alice Johnson (1859–1924) was Moses's daughter. According to a census document of July 14, 1860, she was 10 months old and thus was born in September 1859, and conceived at the very beginning of 1859.[13] Moses was 14. Her mother was Isabella, a "beautiful mulatto housemaid" of his father;[13]:148 she was 23 at the time of the census. That Moses's father Jacob knew of the incident has been questioned,[13]:148 but he could not help but know that Isabella was pregnant and gave birth to a daughter. Isabella, with Alice, visited Moses in Rome, but returned shortly thereafter. Moses never refers to her in his Memoirs, and there is no record of any other contact between them. She married Daniel Hale Williams, a pioneering heart surgeon.[14]

Virginia Military Institute and Civil War

When Fort Sumter was fired upon and Virginia seceded, Ezekiel enrolled in the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia,[7] the first Jewish cadet (student) to do so.[15] He was Corporal of the Guard that accompanied the coffin of Stonewall Jackson (a Virginia Military Institute instructor) at his burial in Lexington in 1863.[8]:43[10] He and other cadets from VMI marched 80 miles north and fought at the 1864 Battle of New Market. He was wounded in a fight with Union army troops under Franz Sigel. After his recovery, he served with the cadets in Richmond to train new recruits for the army. Shortly before the end of the war, he served in the trenches defending the city.[16]

Early career

Following the Civil War, Ezekiel returned to VMI to finish his education, graduating in 1866. He studied anatomy at the Medical College of Virginia in 1866–1868, thinking of becoming a doctor.[4]:127–128[8]:17 In 1867–1868, he was superintendent of the Richmond Hebrew Sunday School.[17]

He moved in with his parents in Cincinnati in 1868; his parents had moved there, where their oldest daughter Hannah lived, after losing their business in Richmond to fire.[4]:128[8]:17 In Cincinnati he began the study of sculpture,[2] studying at the Art School of J. Insco Williams and in the studio of Thomas Dow Jones.[4]:130[16] While not there long, in his memoirs he calls Cincinnati his home.[18]

Moving to Berlin in 1869, he studied at the Prussian Academy of Art under Professor Albert Wolf. In 1872 he met there Fedor Encke (1851–1926), the "illegitimate grandson of King Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia."[3] Encke was a portrait painter later commissioned to do portraits of Theodore Roosevelt and John Pierpont Morgan, among others; he also painted Ezekiel.[8]:i Thay was the beginning of "a forty-five year homosexual relationship…that neither acknowledged publicly"[7] although he referrsd to Encke as "my dear friend".[4]:209 "The couple traveled together often and socialized with Europe's elites, including Hungarian composer Franz Liszt, French actress Sarah Bernhardt and Queen Margherita of Italy."[3] Encke accompanied Ezekiel on a visit to the United States.[8]:49

Needing money, in 1873, during the Franco-Prussian War, he was a war correspondent for the New York Herald,[19]:4 and he was arrested and imprisoned "for a time" as a spy for France.[6] He was admitted into the Society of Artists, Berlin, and at age 29 was the first foreigner to win the Michael Beer Prix de Rome, for a bas relief entitled Israel. The prize of $1,000 provided for two years of study in Rome,[20]:229 but he traveled to Rome by way of the United States, where he had not been for five years,[4]:166 as he had "unexpectedly" received a commission from B'nai B'rith for a monument to Religious Liberty.[4]:164[8]:41

In Rome

Arriving in Rome in 1874, he fell in love with the Eternal City, which he soon made his home. It was there that he completed the sculptures and paintings for which he is famous.

"Ezekiel found both personal and artistic freedom in Rome. He dressed like a dandy and spent extravagantly on entertaining friends, clients, and potential clients."[7] His studio in Rome was in the former Baths of Diocletian, where every Friday afternoon he had open house.[20]:233 It was called "one of the Show Places of the Eternal City, magnificent in proportions and stored with fine art works,"[21] and many visitors have left us descriptions of it.[19]:24

Perhaps the most characteristic of his creations was the celebrated studio.… Here in the vaulted thermae built in the days of Diocletian he had gathered together treasures from many lands and ages. Ancient marbles and alabasters, bronzes, costly metals and relics beautified with precious stones, medieval parchments and church ornaments, oriental ivories, velvets and silks hung on all sides, in alluring contrast to the latter-day furniture and the twentieth century grand piano, proclaiming the broad sympathies and the catholic tastes of this citizen of the world.[22]:230

Under a leafy arbor, a paved stairway leads up to a vineclad terrace, from which you have an extensive view of the surroundings. Doves have built their nests in the masonry and flit fearlessly to and fro about you. Works of art, vases, fragments of old armor, antique heads and ornaments gleam through the dark foliage. Artists' hands have appropriately ornamented the interior of the high hall; pillars, rich with carving of vines, uphold the arches; lamps and statuettes occupy the mantels; tapestries and paintings adorn the walls. Hours might be spent in examining the works of art, great and small, in this wondrous room. Nothing is commonplace: every seat, every cloth, every cup and dish, every furnishing, bears its individual stamp. And yet this immense hall is a wonderfully cozy place, with its many retired nooks where you may settle yourself comfortably and admire and enjoy the casts of the sculptor's busts and statues all about you. A company, among whom were members of the court, [of] foreign ambassadors and their ladies met here recently to view the artist's latest work before he sent it to its destination beyond the Atlantic. For this purpose they descended into a lower hall, where the chiseling in marble is done. There, on her last couch, they saw a beautiful, tranquil woman, in flowing robes…the breath of life seemed to have just flown; nothing rigid marked the eternal slumber.[23]

"His picturesque studio in the Baths of Diocletian was the rendezvous of all important American visitors and the most prominent representatives of art."[6] Among the visitors to his studio were Gabriele d'Annunzio,[4]:201 the Queen of Italy Margherita of Savoy,[4]:414 General and future President Ulysses Grant,[4]:198–199 Franz Liszt,[4]:254 U.S. ambassador to Italy John Stallo,[4]:259 Cardenal Gustav Adolf Hohenlohe,[4] who became a friend, writer Annie Besant,[4]:275 railroad magnate Melville Ingalls,[4]:275 engineer Benjamin Hotchkiss, and Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany.[4]:313 A lecture in his studio was attended by 150 people.[4]:275 He also hosted musicales;[24]:42 "here one heard the finest music by the greatest talent".[4]:233

Ezekiel occupied this studio from 1879 to 1910.[24]:42 After 30 years, the government "demand[ed] the possession of this part of the ruins as an adjunct to the National Museum. On leaving there he was given by the municipal authorities the Tower of Belisarius on the Pincian Hill overlooking the Borghese Gardens, which furnished him a home for the rest of his years, while he took a studio and work rooms in the Via Fausta aandjust off the Piazza del Popolo."[25]

Ezekiel died in his studio in Rome, Italy,[26] and was temporarily entombed there; this was in the middle of the First World War. In 1921, he was reinterred at the foot of his Confederate Memorial in Section 16 of Arlington National Cemetery. The inscription on his grave reads "Moses J. Ezekiel Sergeant of Company C Battalion of Cadets of the Virginia Military Institute."

His works

In the early 1880s, Ezekiel created eleven larger-than-life sized statues of famous artists. These were installed in niches on the façade of the Corcoran Gallery of Art's original building (now the Smithsonian's Renwick Gallery). In the early 1960s, they were removed to the Norfolk Botanical Garden in Norfolk, Virginia.

Although Ezekiel never married, he had a daughter, Alice Johnson (1879-1926). Her mixed-race mother was a maid in Washington, DC, where Johnson grew up. She was in contact with her father throughout his life. After graduating from Howard University, she became a schoolteacher. She married Daniel Hale Williams in 1898, who was also mixed race. He became a prominent, pioneering heart surgeon. They lived in Chicago for much of his career.[27][28]

Among his noted works was a memorial at VMI, Virginia Mourning Her Dead (1903), for which he declined payment.[7] It was installed in the small cemetery where six of the 10 VMI cadets killed at the Battle of New Market are buried. He also created a Confederate memorial which he called New South (1914); it was installed at Arlington National Cemetery. Many of his works were of noted leaders.

Awards and honors

In his lifetime, Ezekiel received numerous honors: he was decorated by King Umberto I of Italy, the "Crosses for Merit and Art" from the German Emperor, another from Prince Frederick Johann of Saxe-Meiningen, and the awards of "Chevalier" (Cavaliere) and "Officer of the Crown of Italy" (1910) from King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy. Ezekiel received the Gold Medal of the Royal Society of Palermo, Italy; the Silver Medal at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri; and the Raphael Medal from the Art Society of Urbino, Italy.

The honorific "Sir" by which Ezekiel is often referred is technically incorrect, as Ezekiel was never knighted by the monarch of the United Kingdom. More properly, his title was "Cavaliere" Moses Ezekiel, because of his Italian knighthood, or Moses "Ritter von" Ezekiel, because of his German honors. Ezekiel translated his Italian title into the English "Sir" on his visiting cards, resulting in the honorific by which he became known in English-speaking countries.[29]

In 1904, he was presented the New Market Cross of Honor at VMI by the Government of Virginia as one of the 294 cadets who fought at the Battle of New Market.

Changing assessments

Although in 1876 he was compared with Michelangelo,[30] Ezekiel's fame has not stood the test of time. "Famous in his day, he is almost forgotten now."[18] "The art world ignored and forgot him because he never innovated; he emulated the classical style of the previous masters…even when the time for that style had come and gone."[2] According to his biographer Peter Nash, "You wouldn't go to Rome to make new, progressive art."[3] "He could not accept modern art", and "rejected" Rodin, who he considered "pretentious".[4]:61, 399–400[31]

"As was his custom with his monuments, Ezekiel proceeded meticulously to reflect historical accuracy,"[4]:37 according to the editors of his memoirs.

[But his works] are utterly devoid of innovations or daring new modes of representation. His prime concern was the literary and historical idea behind the work…. But he failed to realize, like other 19th-century artists, that noble thoughts alone do not guarantee that the works they inspire will be great art… he frequently sacrificed his design to accurate depiction and photographic truth.[5]

Works

Ezekiel apparently did not keep a register of the works he had created, and creating a list is not a trivial task. Some of them have been moved, in some cases more than once. Sometimes dates found are of the work's creation, at other times of its installation or unveiling. In some cases the work is known by more than one name. There are clay models both of works he created and of those he did not.

Lists are found in the introduction to his Memoirs,[4]:70–73 in an obituary in Art and Archaeology,[20] and in the New York Times.[6]

A single word that could be applied to Ezekiel's statues, which he frequently used himself,[4]:139, 164, 409, etc. is "colossal": his "genius often asserts itself in colossal figures and emblematic monuments".[32] His never-built statue of Johns Hopkins, founder of Johns Hopkins University, was to have been over 15 feet (4.6 m) high, with a "colossal" bust of Hopkins, in bronze, 21⁄2 times life size.[33] His most important statues are huge, and in one case he claimed that it was the largest statue ever made.

- Statues

- Religious Liberty (1876). A commission frim B'nai Brith Originally installed in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, now installed at the National Museum of American Jewish History in the same city. "Colossal."[20]:230–231

- 11 statues of artists: Phidias, Raphael, Durer, Michelangelo, Titian, Murillo, Da Vinci, Correggio, Van Dyke, Canova, Thomas Crawford (1879–84). Originally installed in niches on the façade of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Now installed at "Statuary Vista", Norfolk Botanical Garden, Norfolk, Virginia.[34] There is currently (2013) a campaign to restore them.[35]

- Statuette of Spinoza, 1883, Hebrew Union College. Donated by the artist for fundraising.[36]

- Mrs. Andrew Dickson White (Mary Amanda Outwater), 1889, Sage Chapel, Cornell University

- Statue of Christopher Columbus (1892), Arrigo Park, Chicago, Illinois.[37] Bronze, "faced with gold mosaic". Commissioned for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition (Chicago World's Fair), which Ezekiel attended. Placed over the entrance to the Columbus Memorial building.[38]

- Jesse Seligman monument, 1895

- Jefferson Monument (1901), Louisville Metro Hall, Louisville, Kentucky.

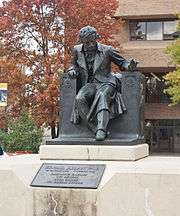

- Virginia Mourning Her Dead (1903), Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, Virginia. "Colossal."[20]:234

- A replica of this is at the former Museum of the Confederacy, now the American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia.

- Statue of Anthony J. Drexel (1904), Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- A 1910 replica of this is at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia.

- Blind Homer with His Student Guide 1881? (1907), University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia.

- Jennie McGraw Fiske, 1908, Sage Chapel, Cornell University

- Statue of Stonewall Jackson (1910), West Virginia State Capitol, Charleston, West Virginia.[39]

- Southern, at the Confederate Cemetery on Johnson's Island, Ohio, a 1910 commission from the United Daughters of the Confederacy, is 19 feet (5.8 m) high;[40] a contemporaneous source says 21 feet (6.4 m).[41] The island had been during the war a prison camp in which captured Confederate soldiers were confined. The statue "represents a Southern soldier, with one hand clutching a musket, and the other raised above the eyes, giving the figure as a whole, the appearance of peering into the distance, faces [sic] south." Ezekiel "contributed" the statue.[41]

- Confederate Memorial (1914), Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia.[42]

- Edgar Allan Poe (his last work), 1915, Wyman Park, Baltimore, Maryland

- Date and present location unknown: statue of Neptune, for Nettuno, Italy

- Reliefs

- Israel, 1873 (Skirball Museum, Los Angeles)

- Jacob Ezekiel, the artist's father, 1874 (Skirball Museum, Los Angeles)

- Catherine Ezekiel, the artist's mother, 1874 (Skirball Museum, Los Angeles)

- Busts

chronological:

- Robert E. Lee (1886), Virginia Military Institute Museum

- Isaac Mayer Wise! Hebrew Union College, Cincinnati

- Goldwin Smith, 1906, Goldwin Smith Hall, Cornell University

- Head of Anthony J. Drexel (1905), Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- Bust of General Robert E. Lee

- Bust of Percy Bysshe Shelley in the Keats-Shelley Memorial House, Piazza di Spagna, Rome.

- Bust of Franz Liszt.

- Bust of Jessica (1880), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.[43]

- Bust of Judith (c. 1880), Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati, Ohio.[44]

- In 1888 he completed a bust of Hopkins professor Charles D. Morris.[33]

- Ecce Homo (1884), Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati, Ohio.[45]

- Bust of Thomas Jefferson (1888), United States Capitol, Washington, DC.[46]

He excelled in portrait busts and executed many of them in marble and bronze; that of “Washington,” now in the Cincinnati Art Museum, giving him his professional start in Berlin. Those of Franz Liszt and Cardinal Gustave von Hohenlohe gained for him the Knighthood for “Science and http://collections.americanjewisharchives.org/ms/ms0044/ms0044.html

.

- Christ in the Tomb[20]:231

- Napoleon at St. Helena

- The Martyr, or Christ Bound to the Cross

- David Singing his Song of Glory

- Judith Slaying Holofernes

- Jessica

- Portia

- Stonewall Jackson statue for Charleston, West Virginia, and a replica for Lexington, Virginia;

- the allegorical Jefferson Monument for Louisville, Kentucky, and a replica in front of the University of Virginia at Charlottesville

- Lord Sherbrooke Memorial in Westminster Abbey, London, England

- Senator Daniels at Lynchburg, Virginia

In an obituary in the New York Times, almost identical to one in American Art News, after mentioning the busts of his friends Cardinal Hohenlohe, Franz Liszt, to whom he was introduced by Hohenlohe, and the Grand Duke of Saxe Meiningen,

- Bust of Washington ("colossal"[47]:189)[19]:5) in the Cincinnati Art Museum.

'The Sailor Boy,' 'Grace Darling', and 'Mercury,' owned by Mrs. Hannah E. Workman of Cincinnati, t

he the bronze bust of Robert E. Lee for H. C. Ezekiel of Cincinnati, bas reliefs of 'Pan' and 'Amor' for Mrs. Charles Fleischmann of Cincinnati; marble torso 'Judith' for Mrs. Bellamy Storer, marble bust of 'Christ; for J. N. McKay of Baltimore, bronze bust of General Hotchkins in the Navy Yard, Washington, marble statue 'Lee a Boy' in Westmoreland, Va.; a monument to Jesse Seligman at the Jewish Orphan Asylum, N. Y., a colossal statue of Columbus, Columbus Memorial Building, Chicago; heroic bronze monument to Thomas Jefferson at Louisville, and 'The Outlook' for the Confederate Cemetery at Johnson's Island, Ohio. He also executed the Fountain of Neptune for the City of Netturno, Italy, and busts of many prominent persons both here and abroad."[6][21]

The following list of his major works is

- Napoleon of St. Helena, statue in Rome, Italy.

- Eve Hearing the Voice (1876), Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati, Ohio.[48]

- Faith (1877), Peabody Institute, Baltimore, Maryland.[49]

- A replica of this is at the Virginia Military Institute.

- Bust of Governor Andrew Gregg Curtin (1912), Smith Memorial Arch, West Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[50]

- Statue of John Warwick Daniel, (c. 1913), Lynchburg, Virginia.

- Statue of Edgar Allan Poe (1917), University of Baltimore, Baltimore, Maryland.[51]

http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/sources.asp?b=Ezekiel_Moses_Jacob_1844-1917

The Life and Times of Moses Jacob Ezekiel: American Sculptor, Arcadian Knighy

Peter Adam Nash. 2014 . Nash, Peter Adam.

Ezekiel, Moses Jacob, 1844-1917. Sculptors — United States — Biography. Jewish artists — United States — Biography. 1. Spanish Roots -- 2. Youth and War -- 3. Europe: The Awakening -- 4. "Ecco Roma"—5. Baths of Diocletian—6. Swarming Beliefs and Causes—7. Against the Tide—8. Trials and Tribulations—9. Final Years.

Legacy

Ezekiel is the sculptor Askol in Carel Vosmaer's novel The Amazon, in which Ezekiel's studio is described in detail,[4]:15[52] It is also described in Mary Agnes Tincker's The Jewel in the Lotus;[4]:66[53] "the opening pages depict the studio of Salathiel, the sculptor, the original of which character in the novel was Moses Ezekiel."[19]:27

A poem about his Israel was written by Pietschmann, of Berlin (the source does not give his first name),[19]:10–11

Gabriele d'Annunzio wrote a poem, "To Mole Ezekiel", in 1887.[4]:459

Another description of his studio, by Lilian V. de Bosis, was published in the May, 1891, issue of 'kTye Esquiline.[19]:25–26

Archival material

The American Jewish Archives, in Cincinnati, has a "Moses Jacob Ezekiel Collection." It "includes original and photocopies of Ezekiel's correspondence and writings, photographs of many of his works, biographies, genealogies, memorial tributes, correspondence of Ezekiel's biographers, articles and newsclippings concerning Ezekiel and miscellaneous items." http://collections.americanjewisharchives.org/ms/ms0044/ms0044.html

Virginia Military Institute has two boxes of Ezekiel papers. "Included is correspondence to Virginia Military Institute Superintendent Edward West Nichols and others, 1867 – 1917, some relating to the design of the Battle of New Market memorial sculpture Virginia Mourning Her Dead; pen and ink sketches by Ezekiel (ca. 67 items); the typed manuscript of Ezekiel's autobiography, Memoirs from the Baths of Diocletian, and miscellaneous printed material."[16] Ezekiel's Memoirs, a fundamental source, were unknown until they were rediscovered in the Hebrew Union Archives by the two rabbis, who after much editorial work, prepared them for publication in 1975. They were called "gossipy" but "readable" in a review.[1]

Some additional material is in the archives of Congregation Beth Ahabah, of Richmond,[10] which contains the archive of Jacob Ezekiel's synagogue, Kahal Kadosh Beth Shalome, the Hebrew Union College of Cincinnati, on whose board of directors Jacob was secretary, and the organizations such as B'nai Brith and United Daughters of the Confederacy that commissioned sculptures.

Gallery

Bas relief of Sarah Workum, private collection.

Bas relief of Sarah Workum, private collection. Virginia Mourning Her Dead (1903), Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, VA.

Virginia Mourning Her Dead (1903), Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, VA. Anthony J. Drexel (1904), Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA.

Anthony J. Drexel (1904), Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA.- Bust of Anthony J. Drexel (1905), Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA.

Homer (1907), University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

Homer (1907), University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA. The Lookout (1910), Confederate Cemetery, Johnson's Island, OH.

The Lookout (1910), Confederate Cemetery, Johnson's Island, OH.- Jefferson Monument (1910), University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

- Bust of Andrew Gregg Curtin (1912), Smith Memorial Arch, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Confederate Memorial (Arlington National Cemetery) (1914), Arlington, VA.

Confederate Memorial (Arlington National Cemetery) (1914), Arlington, VA. Statue of Edgar Allan Poe (1917), University of Baltimore, Baltimore, Maryland.

Statue of Edgar Allan Poe (1917), University of Baltimore, Baltimore, Maryland.

'

In popular culture

Ezekiel was portrayed by Josh Zuckerman in the 2014 film Field of Lost Shoes, which depicted the Battle of New Market.

See also

References

- Lindquist-Cock, Elizabeth (May 1, 1975). "Moses Jacob Ezekiel (Book Review)". LJ: Library Journal. 100 (9). pp. 841–842.

- Eisenfeld, Sue (February 2018). "Moses Ezekiel: Hidden in Plain Sight". Civil War Times Magazine.

- Moehlman, Lara (September 21, 2018). "The Not-So Lost Cause of Moses Ezekiel". Moment.

- Ezekiel, Moses Jacob (1975). Gutmann, Joseph; Chyet, Stanley F. (eds.). Memoirs from the Baths of Diocletian. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0814315255.

- Eisenfeld, Sue (December 1, 2017). "Should We Remove Confederate Monuments — Even If They're Artistically Valuable?". The Forward.

- "American Sculptor, Moses Ezekiel, Dies [obituary]" (PDF). New York Times. March 28, 1917.

- Feldberg, Michael (May 15, 2018). "Sir Moses Jacob Ezekiel: The Jew Who Sculpted Confederate Monuments". Artes Magazine. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- Cohen, Stan; Gibson, Keith (2007). Moses Ezekiel : Civil War soldier, renowned sculptor. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company. ISBN 9781575101316.

- "Jacob Ezekiel (necrology)". Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society. Vol. 9. 1901. pp. 160–163. JSTOR 43058859.

- Heltzer, Herbert L. (February 2012). "Moses Ezekiel: The Search for a Reputation" (PDF). Generations: Jewish Voices of the Civil War. 12 (1). pp. 14–16. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- "B'nai B'rith Members Plan to Revive Local Branch on 90th Anniversary of Order". Syracuse Herald. October 16, 1932. pp. 1, 6.

- "Mrs. Jacob Ezekiel". Richmond Dispatch. July 12, 1881. p. 2.

- Buckler, Helen (1954). Doctor Dan : pioneer in American surgery. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. OCLC 964464.

- O'Brien, Peg (June 16, 1954). "Famous Negro Surgeon Once Was Barber Here". Janesville Daily Gazette (Janesville, Wisconsin). p. 22.

- "Moses Ezekiel". Hallowed Ground. American Battlefield Trust. Summer 2010.

- Virginia Military Institute Archives. "Moses J. Ezekiel papers". Retrieved February 28, 2019./

- "Examination of the Richmond Hebrew Sunday School". Richmond Dispatch. July 3, 1868. p. 1.

- Findsen, Owen (October 26, 1986). "Sculptor Moses Ezekiel 'Rediscovered'". Cincinnati Enquirer. p. 46.

- Philipson, Rabbi David (1922). "Moses Jacob Ezekiel". Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society. 28. pp. 1–62.

- Bush-Brown, Henry K. (1921). "Sir Moses Ezekiel: American Sculptor". Art and Archaeology. 11. pp. 227–234.

- "Obituary. Sir Moses Ezekiel". American Art News. March 31, 1917. p. 4.

- Oppenheim, Samson D. (1917). "Moses Jacob Ezekiel". American Jewish Yearbook. pp. 227–232.

- C. M. S. (September 15, 1889). "Gallery and Studio". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 11.

- Chyet, Stanley E. (198). "Moses Jacob Ezekiel: Art and Celebrity" (PDF). American Jewish Archives Journal. 35 (1). pp. 41–51.

- Bush-Brown, Henry K. (June 1921). "Sir Moses Ezekiel American Sculptor". Art and Archaeology. 11 (6). pp. 226–234.

- Levy, Florence Nightingale (1917). American Art Directory, Volume 14. The American Federation of the Arts. p. 322.

- The Booker T. Washington Papers, Vol.9, footnote, p. 396, November 1907, U. of Illinois Press Archived 2007-10-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Helen Buckler, Doctor Dan: Pioneer in American Surgery, (originally published before 1923; reprinted by Nabu Press, 2011), pp. 147-58, 226-27. Another edition, published in 1968, is Buckler's Daniel Hale Williams, Negro Surgeon.

- Making of America Project (1939). The North American Review. University of Northern Iowa.

- Gutmann, Joseph; Chyet, Stanley F. (1975). Memoirs from the Baths of Diocletian (Introduction). Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814315255.

- Kaufman, Ben L. (September 27, 1975). "HUC Alumni Save Document". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- Morais, Henry Samuel (1894). The Jews of Philadelphia: Their History from the Earliest Settlements to the Present Time. Philadelphia.

- "Johns Hopkins. The Effort to Erect a Monument to His Memory to Be Renewed". Baltimore Sun. September 23, 1892. p. 8.

- Statuary Vista Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine from Norfolk Botanical Garden.

- NorfolkTV (October 10, 2013), Moses Ezekiel Statues from the 1800s, City of Norfolk

- "Artists and Charity". American Israelite (Cincinnati, Ohio). October 12, 1883. p. 7.

- Columbus Statue from Waymarking.com.

- "Items of Interest. Chicago". Jewish South. November 24, 1893. p. 7.

- "Stonewall Jackson". Archived from the original on 2019-02-26. Retrieved 2011-03-10.

- United States Department of Veterans Affairs. "Confederate Stockade Cemetery". Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- "Unveil Monument to Mark the Resting Place of Two Hundred and Six Confederate Soldiers". Sandusky Daily Register. June 8, 1910. pp. 1 and 7.

- Confederate Soldiers Memorial from Arlington National Cemetery.

- Jessica from Flickr.

- Judith from Cincinnati Art Museum.

- Ecce Homo, (sculpture) from Smithsonian Institution CollectionsSearchCenter.

- Jefferson from U.S. Senate.

- Virginia, University of (April 1907). "The Ezekiel Bronzes". The Alumni Bulletin. 7 (2): 188–192.

- Eve Hearing the Voice from Cincinnati Art Museum.

- Faith from Peabody Art Collection.

- Governor Curtin bust from Philadelphia Public Art.

- Poe Statue Archived 2010-12-25 at the Wayback Machine from University of Baltimore Law School.

- Vosmaer, Carl (1884). The Amazon. New York: T. F. Unwin..

- Tincker, Mary Agnes (1884). The Jewel in the Lotus. London: J.B. Lippincott & Co.

Bibliography

- Cohen, Stan and Keith Gibson. Moses Ezekiel: Civil War Soldier, Renowned Sculptor, Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, Inc., 2007. ISBN 1-57510-131-9

- "Obituary. Sir Moses Ezekiel". American Art News. March 31, 1917. p. 4.

- Ezekiel, Moses Jacob (1975). Gutmann, Joseph; Chyet, Stanley F. (eds.). Memoirs from the Baths of Diocletian : or Memoirs of a Southern veteran. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-1525-5.

First publication.

- Leepson, Marc. "Sculpting the Cause", Civil War Times Illustrated, Vol. 46, Issue 9, November–December 2007.

- Nash, Peter Adam (2014). The Life and Times of Moses Jacob Ezekiel: American Sculptor, Arcadian Knight. Madison–Teaneck, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-1611476712.

- "Ezekiel, Sculptor, Arrives: Here to Attend Unveiling of His Statue of Jefferson in Charlottesville". New York Times. May 25, 1910. p. 9.

- Wrenshall, Katharine H. (November 1909). "An American Sculptor In Rome: The Work of Sir Moses Ezekiel". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XIX: 12255–12263. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

Video

- NorfolkTV (October 10, 2013), Moses Ezekiel Statues from the 1800s, City of Norfolk

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Moses Jacob Ezekiel. |