Monokini

The monokini, designed by Rudi Gernreich in 1964, consisting of only a brief, close-fitting bottom and two thin straps,[1] was the first women's topless swimsuit.[2][3] His revolutionary and controversial design included a bottom that "extended from the midriff to the upper thigh"[4] and was "held up by shoestring laces that make a halter around the neck."[5] Some credit Gernreich's design with initiating,[3] or describe it as a symbol of, the sexual revolution.[6]

Gernreich designed the monokini as a protest against a repressive society. He didn't initially intend to produce the monokini commercially,[7] but was persuaded by Susanne Kirtland of Look to make it available to the public. When the first photograph of a frontal view of Peggy Moffitt wearing the design was published in Women's Wear Daily on June 3, 1964,[8] it generated a great deal of controversy in the United States and other countries. Gernreich sold about 3000 suits, but only two were worn in public. The first was worn publicly on June 22, 1964 by Carol Doda in San Francisco at the Condor Nightclub, ushering in the era of topless nightclubs in the United States, and the second at a beach in Chicago in July 1964 by artist's model Toni Lee Shelley, who was arrested.

Some manufacturers and retailers refer to modern monokini swimsuit designs as a topless swimsuit, topless bikini,[9] or unikini.[10]

Etymology

Gernreich may have chosen his use of the word monokini (mono meaning 'single') through back-formation by interpreting the bi of bikini as the Latin prefix bi- ('two'), denoting a two-piece swimsuit.[11][12] But in fact the bikini swimsuit design was named by its inventor Louis Réard after the Bikini Atoll in the Pacific, five days after Operation Crossroads, the first peace-time test of nuclear weapons, took place there. Réard hoped his design would have a similarly explosive effect.[13][14]

Background

Austrian-American fashion designer Rudi Gernreich had strong feelings about society's sexualization of the human body and disagreed with religious and social beliefs that the body was essentially shameful.[15] Gernreich grew up in Austria where its citizens were advocates of exercising nude, a rejection of the over-civilized world.[7] His father Siegmund Gernreich was a stocking manufacturer who committed suicide when Gernreich was 8. In 1939, his mother took him and they fled the country to escape Hitler, who among other things had banned nudity.[7] In Los Angeles, Gernreich became an advocate of sexual liberation. He co-founded in 1950 the first homosexual social group advocating for gay rights that became the Mattachine Society.[16] He thought government restraints on nudity were fascist and oppressive.[7]

Reputation

Gernreich developed a reputation as an avant-garde designer who broke many of the rules, and his swimsuit designs were unconventional. In its December 1962 issue, Sports Illustrated remarked, "He has turned the dancer's leotard into a swimsuit that frees the body. In the process, he has ripped out the boning and wiring that made American swimsuits seagoing corsets." [17] That month he first envisioned[17] creating a topless swimsuit which he called a monokini.[18]

Origins

Gernreich had predicted in a September 1962 issue of Women’s Wear Daily that "Bosoms will be uncovered within five years." At the end of 1963, editor Susanne Kirtland of Look called Gernreich and asked him to submit a design for the suit to accompany a trend story along futuristic lines.[8] He resisted the idea at first, but said, "It was my prediction. For the sake of history, I didn't want Pucci to do it first.[7][19] Gernreich found the design more difficult than the expected. His initial designs looked like trunks or boxer shorts.[19] He felt the swimsuit ought to just be bikini bottoms, but realized that this wouldn't constitute a unique design. He initially designed a Balinese sarong that began just under the breasts, but Kirtland didn't feel the design was bold enough and needed to make more of a statement. Gernreich finally chose a design that ended around mid-torso and then added two straps that rose between the breasts and were tied around the neck.[8] The first two initial attempts to cut the design failed.[19] When a photo shoot was arranged on Montego Bay in the Bahamas, all five models hired for the session refused to wear the design. The photographer finally persuaded a local prostitute to model it.[20]

As a statement

Gernreich did not originally intend to produce the swimsuit commercially. It had more meaning to Gernreich as an idea than as a reality.[21] Gernreich had Moffitt model the suit in person for Diana Vreeland of Vogue, who asked him why he conceived of the design. Gernreich told her he felt it was time for "freedom-in fashion as well as every other facet of life," but that the swimsuit was just a statement. He said, “[Women] drop their bikini tops already,” he said, “so it seemed like the natural next step.”[7] She told him, "If there's a picture of it, it's an actuality. You must make it."[22] Gerenrich said in television interview, "It may well be a bit much now. But, just wait. In a couple of years topless bikinis will be a reality and regarded as perfectly natural."[23]

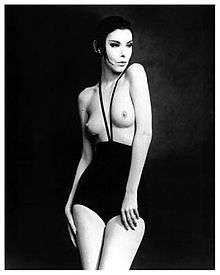

Design pictures

To avoid letting others sensationalize the swimsuit and to retain some control of the design, Gernreich asked William Claxton, the husband of Gernreich's usually sole model Peggy Moffitt,[24] to take pictures of his wife in the yellow wool swimsuit.[6] Claxton, Moffitt, and Gernreich wanted to publish their own pictures for the fashion press and news media, and Gernreich gave pictures of Moffit modeling the monokini to a carefully selected handful of news organizations.[22][25]

Moffitt was initially resistant to the idea of posing topless. She said, "I didn’t want to do it when he asked me. I am a puritanical descendent of the Mayflower. I carried that goddamned Plymouth Rock on my back. When I did give in, I did so with a lot of rules. I would not show myself on the runway that way. I’d do it only with Bill. Since Rudi would never ever have enough money to do this, I did it for free. But I had final say on everywhere it went photographically."[26] Look published a rear view of the prostitute from Montego Bay modeling the swimsuit on June 2, 1964.[8][27][28] Claxton took his pictures of Moffit to Life but they said they could only print pictures of naked breasts "if the woman is an aborigine." Claxton took additional pictures of Moffit especially for Life with her arms covering her breasts. The picture was one of several images of Moffit in a story about the historical evolution of the breast in fashion history from 1954 to 1964.[19] Moffit said, "The photograph of me in that issue—hiding my breasts with my arms—is dirty. If you are wearing a fashion that does not have a top as part of its design and hold your arms over your bosom, you're going along with the whole prudish, teasey thing like a Playboy bunny."[22]

Initial notice

The following day columnist Carol Bjorkman of Women's Wear Daily published Claxton's frontal view of Moffitt wearing the suit.[8] It became a celebrated image of the extremism of 1960s designs.[29] Moffit later said, "It was a political statement. It wasn't meant to be worn in public."[24] On June 12, 1964 the San Francisco Chronicle featured a photo of a woman in a monokini with her exposed breasts clearly visible on its front page.[30] Claxton's frontal image of Moffit modeling the swimsuit was subsequently published by Life and numerous other publications. Life writer Shana Alexander noted, "One funny thing about toplessness is that it really doesn't have much to do with breasts. Breasts of course are not absurd; topless swimsuits are. Lately people keep getting the two things mixed up." She mocked the swimsuit design as a "joke".[19] The photo catapulted Moffitt into instant celebrity, reportedly resulting in her receiving everything from marriage proposals to death threats.[24] Moffitt and Claxton later wrote The Rudy Gernreich Book, described as an aesthetic biography of the fashion revolutionary.[31][A]

Instant attention

"I thought we'd sell only six or seven, but I decided to design it anyway."[32] But when the design got worldwide notice, orders for the non-existent suit poured in until over 1,000 orders were pending.[19] Despite the reaction of fashion critics and church officials, Harmon Knitwear made over 3,000 monokinis.[4] Gernreich first sold the suit to the Joseph Magnin department store in San Francisco, where it was an instant hit. In New York City, leading stores like B. Altman & Company, Lord & Taylor, Henri Bendel, Splendiferous and Parisette placed orders. On June 16, 1964, Gernreich's topless swimsuit went on sale in New York City.[7] The suit was priced at $24 each.[4][33]

Controversy

Swimsuit as a statement

Gernreich purposefully used his designs to advance his socio-political views. He wanted to reduce the stigma of a naked body, to “cure our society of its sex hang up,” as he put it. Gernreich stated, "To me, the only respect you can give to a woman is to make her a human being. A totally emancipated woman who is totally free."[34]

Gernreich said, "Baring the breasts seemed logical in a period of freer attitudes, freer minds, the emancipation of women."[28][35] Gernreich told Time magazine in 1969, the monokini "is a natural development growing out of all the loosening up, the re-evaluation of values that’s going on. There is now an honesty hangup, and part of this is not hiding the body—it stands for freedom."[32]

Every girl I knew was offended by the dirty-little-boy attitude of the American male toward the American bosom. I was aware that the great masses of the world would find the topless shocking and immoral. I couldn't help feel the implicit hypocrisy that made something in one culture immoral and in another perfectly acceptable.[36]

In January, 1965, he told Gloria Steinem in an interview that despite the criticism he'd do it again.[32]

A designer stands or falls on the totality of each year's collection, not just one item. At the moment, this topless business has done nothing but take away from my work, but in the end, I'm sure having my name known internationally will be a help. But that isn't why I'd do it again. I'd do it again because I think the topless, by overstating and exaggerating a new freedom of the body, will make the moderate, right degree of freedom more acceptable.[32]

Moffitt said the design was a logical evolution of Gernreich's avant-garde ideas in swimwear design as much as a scandalous symbol of the permissive society.[37] She said, "He was trying to take away the prurience, the whole perverse side of sex." She said his design was "prophetic." "It had to do with more than what to wear to the beach. It was about a changing culture throughout all society, about freedom and emancipation. It was also a reaction against something particularly American: the little boy snickering that women had breasts."[37]

Los Angeles Times staff writer Bettijane Levine wrote, "His topless was an artistic statement against women as sex objects, much as Pablo Picasso painted Guernica as a statement against war."[36] Over the next few weeks, his design was covered in more than 20,000 press articles.[38]

1985 benefit showing

On August 13, 1985, Los Angeles Fashion Group produced a gala at the Wiltern Theatre to benefit the Rudi Gernreich Design Scholarship Fund. Moffit was a member of the committee. When the group considered showing the Monokini suit during the benefit, Moffitt strongly objected. She told the Los Angeles Times,[36]

Rudi did the suit as a social statement. It was an exaggeration that had to do with setting women free. It had nothing to do with display, and the minute someone wears it to show off her body, you've negated the entire principle of the thing. I modeled it for a photograph, which was eventually published around the world, because I believed in the social statement. Also, because the three of us—Rudi, Bill, and I—felt that the photograph presented the statement accurately.[36]

The regional director of the Fashion Group, Sarah Worman, believed that the swimsuit was "the single most important idea he ever had—the one that changed the way women dressed all over the Western world." She said Moffitt's refusal to show it on a model didn't make sense when the benefit was modeling everything else he ever did on live models.[36]

Playboy offer

Moffit said in 1985 that she had been offered $17,000 in 1964 (equivalent to $140,000 in 2019)[39] by Playboy to publish Claxton's photograph of her wearing the suit, but refused. "I turned it down as unthinkable. And I don't want to exploit women any more now than I did in 1964. The statement hasn't changed. The suit still is about freedom and not display."[36]

World-wide reaction

There was a strong public reaction to the original swimsuit design. The Soviet Union denounced the suit, saying it was "barbarism" and indicated "capitalistic decay".[30] The Vatican denounced the swimsuit, and the L'Osservatore Romano said the "industrial-erotic adventure" of the topless bathing suit "negates moral sense." Many of Rudi's contemporaries in the fashion industry reacted negatively. In the US, some Republicans tried to blame the suit on the Democrats' stance on moral issues.[21] Gernreich introduced the monokini at a time when U.S. nudists were trying to establish a public persona. The United States Postmaster General had banned nudist publications from the mail until 1958, when the Supreme Court of the United States declared that the naked body in and of itself could not be deemed obscene.[30] Use of the word monokini was first recorded in English that year.[4]

As the suit gained notoriety, the New York City Police Department was strictly instructed by the commissioner of parks to arrest any woman wearing a monokini.[30] In Dallas, Texas, when a local store featured the suit in a window display, members of the Carroll Avenue Baptist Mission picketed until they removed the display.[7] Copious coverage of the event helped to send the image of exposed breasts across the world. Women's clubs and the Catholic church actively condemned the design. In Italy and Spain, the Catholic church warned against the topless fashion.[23]

In France in 1964, Roger Frey led the prosecution of the use of the monokini, describing it as: "a public offense against the sense of decency, punishable according to article 330 of the penal code. Consequently, the police chiefs must employ the services of the police so that the women who wear this bathing suit in public places are prosecuted."[40][41] At St. Tropez on the French Riviera, where toplessness later became the norm, the mayor ordered police to ban toplessness and to watch over the beach via helicopter.[30]

Jean-Luc Godard, a founding mover of French New Wave cinema, incorporated monokini footage shot by Jacques Rozier in Riviera into his film A Married Woman, but it was edited out by the censors.[42] A few defended Gernreich's design. Fashion designers Geraldine Stutz, president of Henri Bendel, said, "I only wish I were young enough to be one of the pioneers myself." Carol Bjorkman, a columnist at Women's Wear-Daily's wrote, "What's the matter with the front? After all, it is here to stay, and it is awfully nice being a girl."[21]

When Toni Lee Shelley, a 19-year-old artists model, wore the topless bathing suit to the North Avenue beach in Chicago, 12 police officers responded, 11 to control and disperse the public and photographers, and one to arrest her.[43][44] She was charged with disorderly conduct, indecent exposure, and appearing on a public beach without suitable attire. At her arraignment she asked for an all-male jury.[22][45] She told the press that the swimsuit was "certainly more comfortable."[44] Shelley was fined US$100 for wearing the swimsuit on a public beach.[30]

Influence

In the 1960s, the monokini influenced the sexual revolution by emphasizing a woman's personal freedom of dress, even when her attire was provocative and exposed more skin than had been the norm during the more conservative 1950s.[30] Quickly renamed a "topless swimsuit",[30] the design was never successful in the United States, although the issue of allowing both genders equal exposure above the waist has been raised as a feminist issue from time to time.[37]

On June 22, 1964, the public relations manager of the Condor Nightclub in San Francisco's North Beach district bought Gernreich's monokini from Joseph Magnin and gave it to former prune picker, file clerk, and waitress Carol Doda to wear for her act. Doda was the first modern topless dancer in the United States,[30]:25 renewing the burlesque era of the early Twentieth Century in the U.S. San Francisco Mayor John Shelley said, "topless is at the bottom of porn."[28] Within a few days, women were baring their breasts in many of the clubs lining San Francisco's Broadway St., ushering in the era of the topless bar.[28] Her debut as a topless dancer was featured in Playboy magazine in April 1965.[30]:25

San Francisco public officials tolerated the topless bars until April 22, 1965, when the San Francisco Police Department arrested Doda on indecency charges. Hundreds of protesters gathered outside the police department, calling for release of both Doda and free speech activist Mario Savio, held in the same station.[28] Doda rapidly became a symbol of sexual freedom, while topless restaurants, shoeshine parlors, ice-cream stands and girl bands proliferated in San Francisco and elsewhere. Journalist Earl Wilson wrote in his syndicated column, "Are we ready for girls in topless gowns? Heck, we may not even notice them." English designers created topless evening gowns inspired by the idea.[30] The San Francisco Examiner published a real estate advertisement that promised "bare top swimsuits are possible here".[28]

Later designs

.jpg)

Going topless reached its highest popularity during the 1970s. In the early 1980s monokini designs that were simply a bikini-bottom (also known as the unikini) became popular.[46] As of 2015, some swimsuit designers continue to produce a variety of monokini or topless swimsuits that women can wear in private settings or in places where topless swimsuits are allowed.[4]

Unlike Gernreich's original design exposing the women's breasts, current designs are one-piece swimsuits that cover the women's breasts but typically include large cut-outs[47] on the sides, back, or front. The cutouts are connected with varying fabrics, including mesh, chain, and other materials to link the top and bottom sections together. From the back the monokini looks like a two-piece swimsuit. The design may not be functional but aesthetic.[48] Some suits are designed with a g-string style back and others offer full coverage.

Pubikini

In 1985, four weeks before his death, Gernreich unveiled the lesser-known pubikini, a topless bathing suit that exposed the wearer's mons pubis.[49][50][51] It was a thin, V-shaped, thong-style bottom[52] that in the front featured a tiny strip of fabric that exposed the wearer's pubic hair.[53][54] The pubikini was described as a pièce de résistance totally freeing the human body.[55]

References

- "Monokini". Free Dictionary. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- Rosebush, Judson. "Peggy Moffitt Topless Maillot in Studio". Bikini Science. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- Alac, Patrik (2012). Bikini Story. Parkstone International. p. 68. ISBN 1780429517. Archived from the original on 2018-01-29.

- "Bikini Styles: Monokini". Everything Bikini. 2005. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- Nangle, Eleanore (June 10, 1964). "Topless Swimsuit Causes Commotion". Chicago Tribute. Archived from the original on 14 September 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- "Fit Celebrates the Substance of Style". Elle. July 5, 2009. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- Bay, Cody (June 16, 2010). "The Story Behind the Lines". Archived from the original on 4 July 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- "The Rudi Gernreich Book". Archived from the original on March 10, 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- "Monokini". Archived from the original on 18 August 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- "Bikini Science". Bikini Science. Archived from the original on 2018-01-27. Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- Gurmit Singh; Ishtla Singh (2013). The History of English. Routledge. pp. 13–14. ISBN 9781444119244. Archived from the original on 2016-12-22.

- Burridge, Kate (2004). Blooming English. Cambridge University Press. p. 153. ISBN 0521548322. Archived from the original on 2018-01-29.

- "The History of the Bikini". Time. July 3, 2009. Archived from the original on September 30, 2013. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- "Swimsuit Trivia History of the Bikini". Swimsuit Style. Archived from the original on 2009-03-09. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- Rielly, Edward J. (2003). The 1960s. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0313312618. Archived from the original on 2014-06-30.

- D'Emilio, John (1983). Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940–1970. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-226-14265-4.

- "Way Out Out West: New Designs For The Sea..." Sports Illustrated. December 24, 1962. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- "Gernreich Bio". Gernreich.steirischerbst.at. Archived from the original on 2016-02-13. Retrieved 2012-11-12.

- Alexander, Shana (July 10, 1964). "Fashion's Best Joke on Itself in Years". Life. 57 (2): 56–57. ISSN 0024-3019. Archived from the original on May 29, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- Kalter, Suzy (May 25, 1981). "20 Remember Those Topless Suits? After a Cool-Out, Racy Rudi Gernreich Returns to the Fashion Swim". People Magazine. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- Smith, Liz (January 18, 1965). "The Nudity Cult". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- "The Rudi Gernreich Book". Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- Thesander, Marianne (1997). The Feminine Ideal. Reaktion Books. p. 187. ISBN 1861890044.

- Walls, Jeanette (January 14, 1991). "High Fashion's Lowest Neckline". New York Magazine. New York Media, LLC. 24 (2): 21. ISSN 0028-7369.

- Feitelberg, Rosemary (November 1, 2010). "Moment 20: Bikinis Beckon". Women's Wear Daily. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- Amorosi, A.D. (September 13–20, 2001). "Q&A: Peggy Moffitt". Philadelphia Citypaper. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- Luther, Marylou (April 22, 1985). "Topless Creator Gernreich Dies: Fashion World Saw Him as Its Most Innovative". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- Shteir, Rachel (1964). Striptease: The Untold History of the Girlie Show. East Pakistan Police Co-operative Society. pp. 318–321. ISBN 0-19-512750-1. Archived from the original on 2017-02-15.

- Jennifer Craik, The Face of Fashion, page 145, Routledge, 1993, ISBN 0203409426

- Smith Allyn, David (2001). Make Love, Not War. Taylor & Francis. pp. 23–29. ISBN 0-415-92942-3. Archived from the original on 2014-01-03.

- The Rudy Gernreich Book (1999), publisher Taschen GmbH, ISBN 3822871974.

- Rockwell, John (June 3, 2014). The New York Times the Times of the Sixties: The Culture, Politics, and Personalities That Shaped the Decade. Black Dog and Leventhal.

- ""The Total Look: Rudi Gernreich, Peggy Moffitt, and William Claxton," Cincinnati Art Museum, through May 24, 2015". March 24, 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- Tay, Michelle (February 24, 2015). "Rudi Gernreich – The Unsung Hero of American Fashion Design". Archived from the original on 23 August 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- Drohojowska-Philp, Hunter (July 2011). Rebels in Paradise: The Los Angeles Art Scene and the 1960s. Henry Holt and Co. p. 98. ISBN 9781429958998.

- Levine, Bettijane (August 2, 1985). "Commentary: Retrospective Keeps Alive the Gernreich Genius for Controversy". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- Menkes, Suzy (July 18, 1993). "RUNWAYS; Remembrance of Thongs Past". New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- Joseph, Alexander. "Beyond the Bared Breast". vestoj. Archived from the original on 29 October 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Situationist International, Sketch of a Morality without Obligation or Sanction Archived 2013-07-09 at the Wayback Machine, Issue No 9, August 1964

- Le Monde, 25 July 1964

- James Monaco, The New Wave, page 157, UNET 2 Corporation, 2003, ISBN 0970703953

- Alexander, Shana (July 10, 1964). "Me? In That!". Life. 57 (2): 55–61.

- "Model arrested for wearing topless swimsuit". Wilmington Morning Star. June 23, 1964. p. 11. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- "Date in Court". Chicago Tribute. July 11, 1964. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- Maynard, Margaret (2001). Out of Line. Sydney, New South Wales, Australia: University of New South Wales Press. p. 156. ISBN 0868405159.

- "Monokini". LoveToKnow. Archived from the original on 2006-12-03. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- Wexler, Kathryn (July 17, 2007). "Swimsuit trends for next spring". The Miami Herald. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- Portraits: Photographs from Europe and America (2004) Klaus Honnef, Helmut Newton and Carol Squiers. page 21, Schirmer, ISBN 382960131X

- Cathy Horn, "Rudi Revisited", The Washington Post, November 17, 1991, page 3

- Elizabeth Gunther Stewart, Paula Spencer & Dawn Danby, The V Book: A Doctor's Guide to Complete Vulvovaginal Health (2002), page 104, Bantam Books, ISBN 0-553-38114-8

- Ellen Shultz, ed. (1986). Recent acquisitions: A Selection, 1985-1986. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 48. ISBN 978-0870994784.

- overzero.com. "Metroland". Metroland. Archived from the original on 2012-07-29. Retrieved 2012-11-12.

- Elizabeth Gunther Stewart, Paula Spencer and Dawn Danby, The V Book, page 104, Bantam Books, 2002, ISBN 0553381148

- Catalog adds options for overweight girls, Denver Post, 1992-01-02

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Monokinis. |